Luxor

Cairo is not only Egypt’s sole city — it’s nowhere near the most interesting one. Indeed, who hasn’t seen the pyramids? So much has been written and filmed about them that they no longer evoke much excitement.

Fortunately, in the south of Egypt, approximately in the middle of the country, lies another city. It is called Luxor. This name, which translates from Arabic as “fortress,” is not widely known, but most people will recall the Greek name of this city, under which it is mentioned in school history textbooks: Thebes.

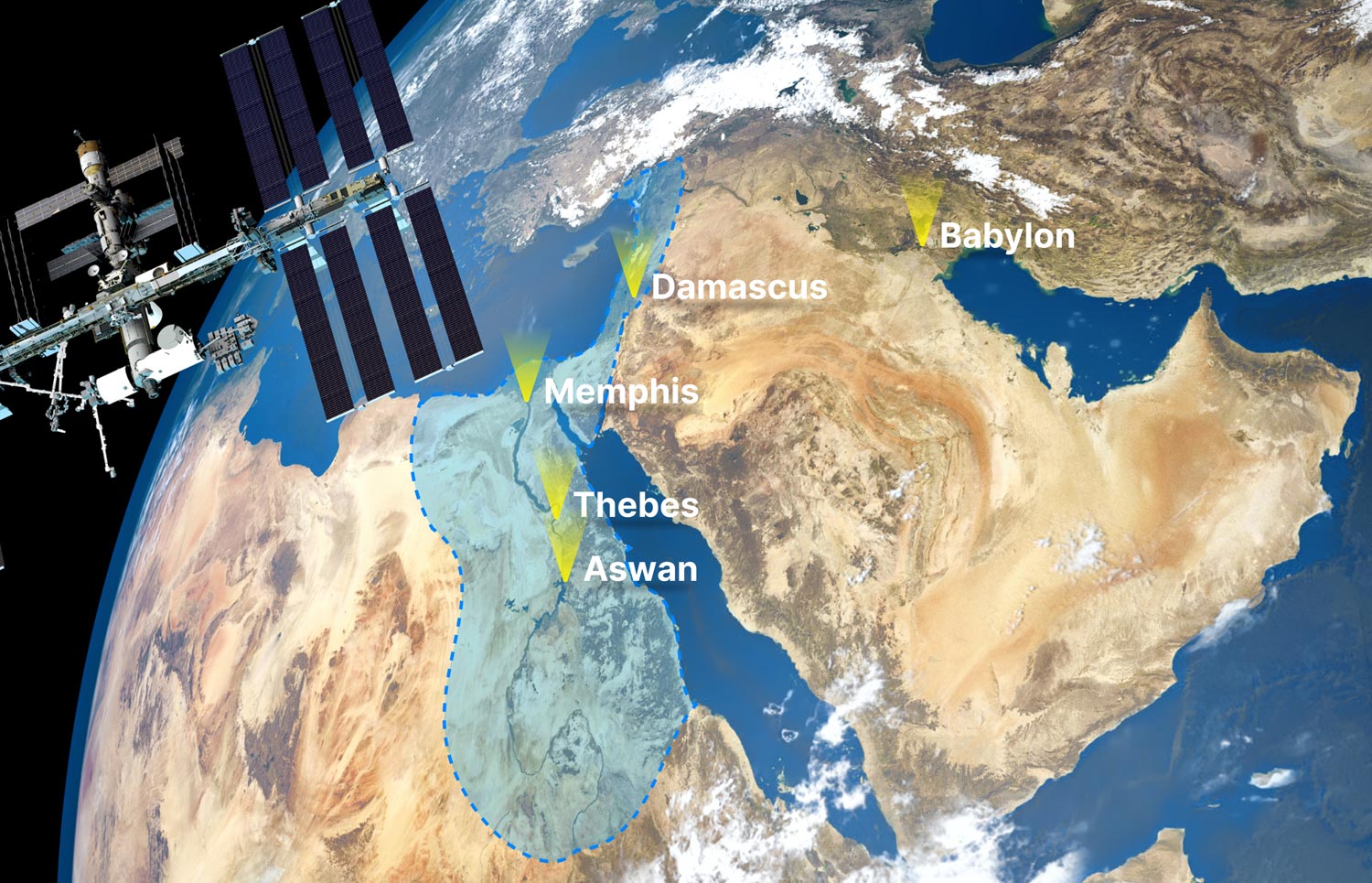

The city of Memphis became the first capital of Egypt as early as 3100 BC and remained so for a thousand years. Then Egypt split into dozens of city-states, which quarreled among themselves and fought for control over the region. Thebes emerged with victory from this anarchy, uniting Egypt into a new country roughly within today’s borders.

Three hundred years later, Egypt experienced another collapse and was then conquered and ravaged by the Hyksos tribes. This new chaos lasted for two hundred years, and once again, it was Thebes that ended it, managing to unify the country for the second time. The new kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, stretched from the Red Sea to Libya and from modern-day Sudan to Turkey.

It was 1500 BC. Thebes reached the height of its power and maintained it for several centuries. According to historians’ estimates, the city could have had about 75,000 inhabitants. It was possibly the largest city in the world at that time.

Like other cities in Egypt, Thebes was located on the Nile River. The river divided the city into two parts. To the east of the Nile was its residential area, which also housed all the significant temples. This part was called the “city of the living.” On the western bank, with its desert and rocky formations, pharaohs built enormous underground tombs for themselves. This part was called the “city of the dead.”

City of the Living

In the city of the living, they live. This is a fairly green part of the city (as much as a city in Egypt can be green). At least there are several palm-lined avenues, and trees can be found among the residential buildings.

In the center of lively Luxor, there is a small but quite decent square. Here it becomes evident that the city is not at all like dusty Cairo, where the center features not a square but a roundabout named after Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

After Cairo, Luxor generally feels like some sort of liberal European provincial town. There are cozy cafes, hipsters, and local kids riding bikes around.

Behind the first row of buildings by the square hides a super-colorful Arab market, which is better avoided by people with epilepsy.

This is how people live here.

It’s not that the housing itself is much different from Cairo, but there’s no such blatant dusty construction in Luxor.

A typical mess on someone’s balcony.

A typical gold shop.

A typical Arab folks.

But let’s return to the square. Right next to it is the Luxor Temple. Its columns are visible against the backdrop of a small lawn with pigeons grazing on it.

It is a fairly compact temple, consisting of two large halls, a colonnade between them, and a sanctuary. Most of the temple can be seen without even going inside; it is clearly visible from the nearby cafes and the road that encircles it.

The main feature of the Luxor Temple isn’t even the dozen statues of Ramses II, who has more monuments in Egypt than Lenin had in the USSR. Much more interesting is that, first, Christianity passed through the temple, turning it into a church and leaving behind a fresco over the hieroglyphs...

...and then Islam, which transformed one of the sanctuaries into a mosque, with its minarets blending perfectly with the pagan statues.

However, this temple is the least impressive of the two great temples located in Luxor. The second temple is called Karnak. It is much larger than the Luxor Temple and is connected to it by a three-kilometer avenue lined with statues of sphinxes along its entire length.

In truth, most of the statues today are just pedestals. Perhaps in the future, some mad dictator will spend half of Egypt’s gold reserves to restore these sphinxes, but for now, a significant portion of the avenue consists of such “stumps.”

The avenue features more than a thousand sphinxes. Most of them have human heads, but closer to the Karnak Temple, sphinxes have ram heads. This is a symbol of the god Amun, in whose honor the temple was originally built.

At first glance, the Karnak Temple doesn’t appear much larger than the Luxor Temple. The main entrance is flanked by the remnants of some wall, which are not particularly impressive.

In reality, Karnak is 30 times larger than Luxor. It is the largest temple complex in Egypt and one of the largest in the world. Additionally, while the Luxor Temple was built in 1400 BC, the Karnak Temple was founded half a millennium earlier, in 1970 BC.

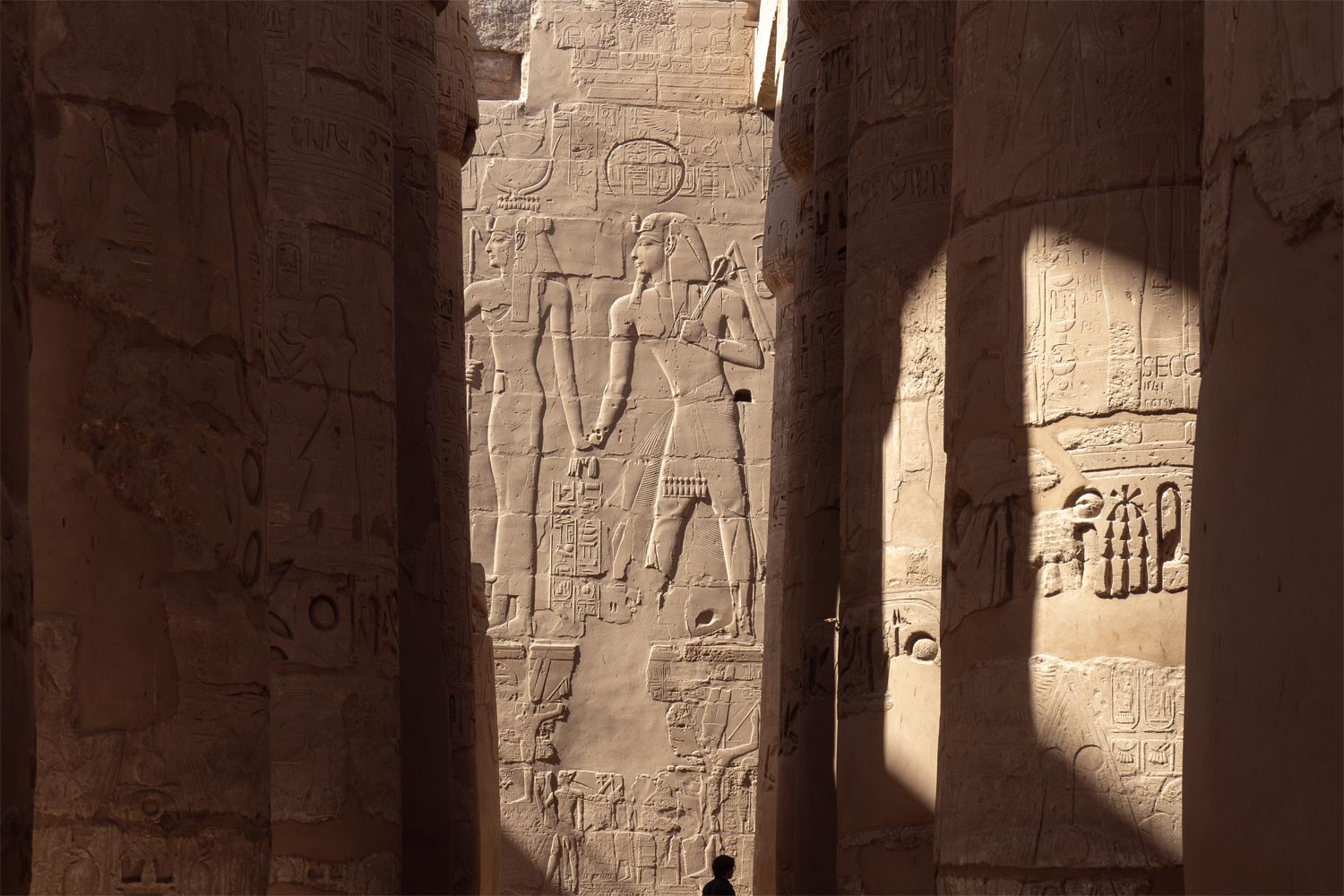

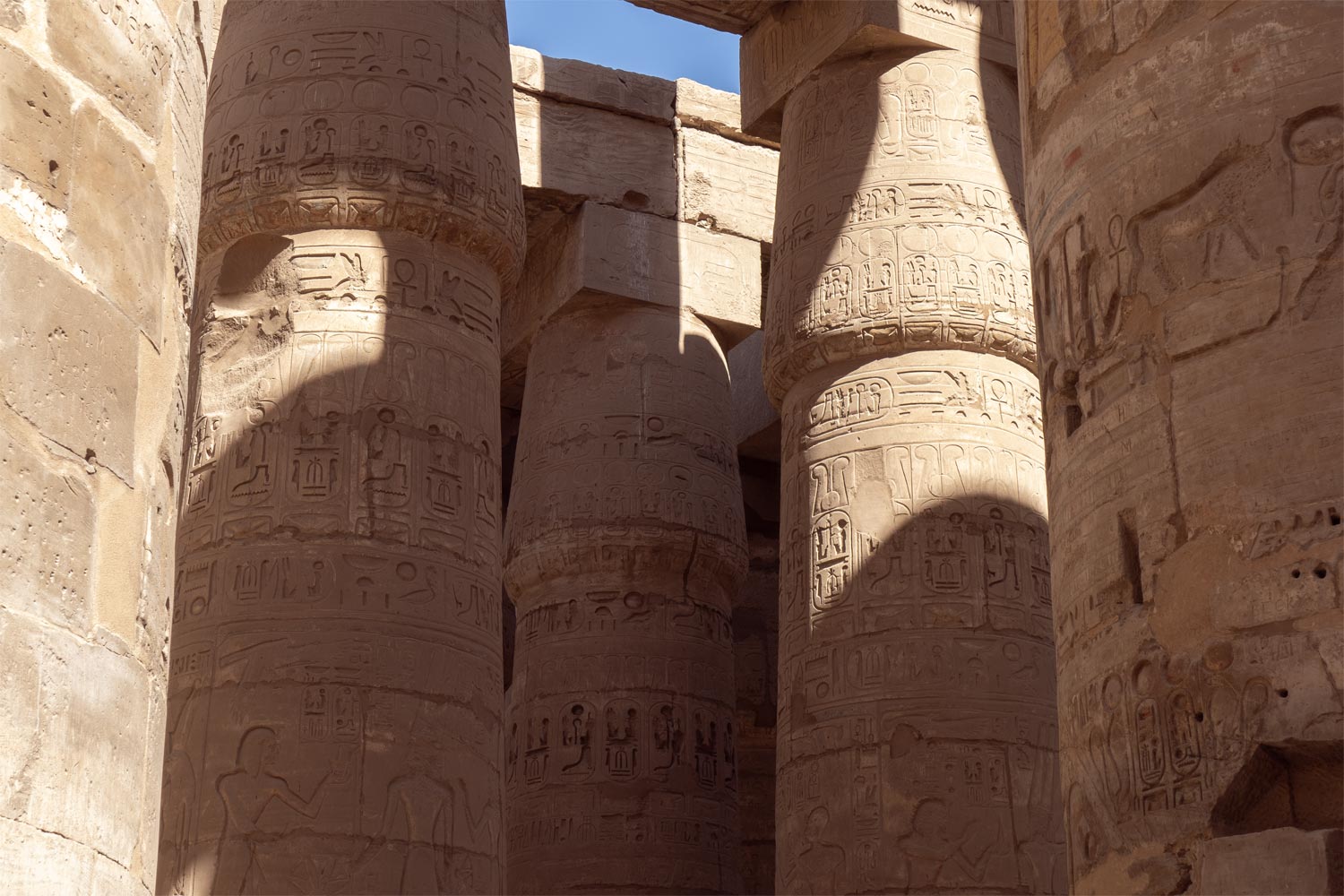

You only grasp the full scale of this temple when you enter it. It becomes clear that against the backdrop of 20-meter columns, people look the size of bugs.

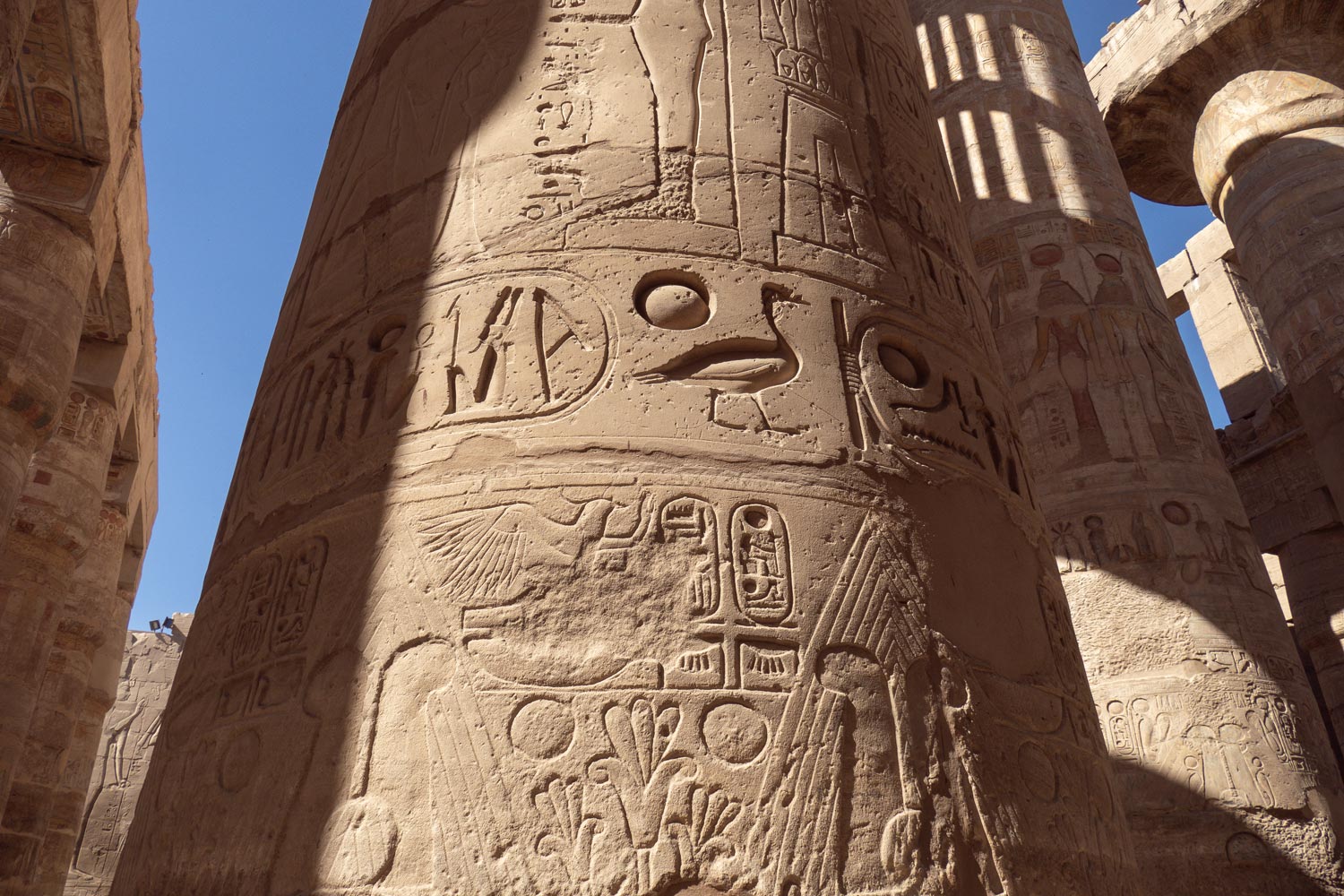

The diameter of some columns reaches three and a half meters. It would take seven people to encircle such a column.

In total, there are more than two hundred columns in the Karnak Temple, with 134 columns in the main hall alone. Long ago, they supported a massive roof. The Egyptians didn’t know how to build triangular roofs of that size, and arches and vaults hadn’t been invented yet. So, the roofs were flat, thick, and extremely heavy.

Only a true forest of columns could support such a roof, which significantly reduced the usable area of the temple.

Every respectable column ends with a capital. Egyptian capitals, the oldest in the world, were made in the form of a lotus flower or, more often, papyrus, as seen in Karnak.

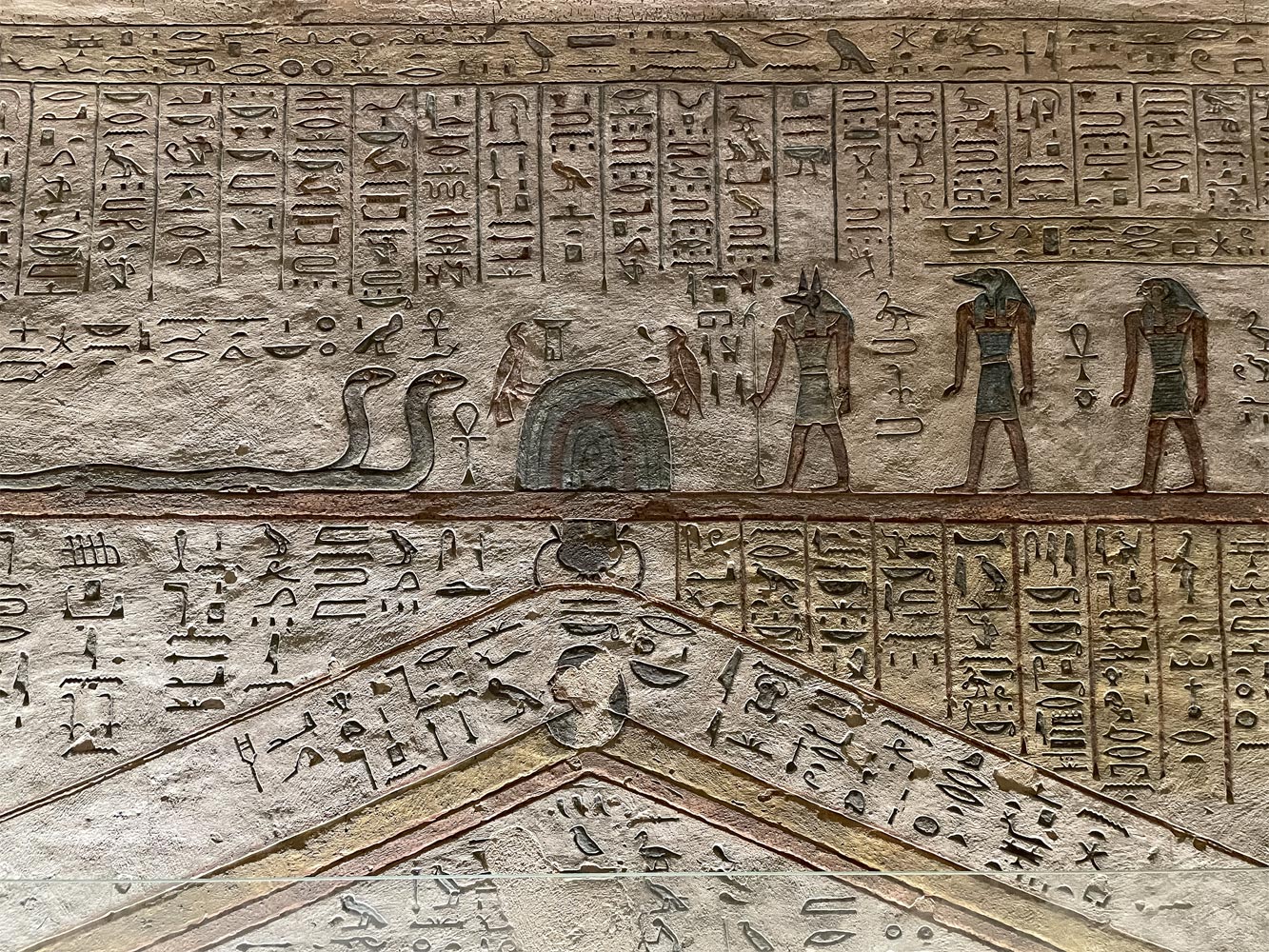

The columns are adorned from top to bottom with bas-reliefs. These typically depict scenes from battles and ceremonies.

Of course, all these drawings were originally painted (just like all Greek and Roman temples and statues were in color). On some columns, remnants of paint have survived, especially at the top, where rain and sun were less likely to reach.

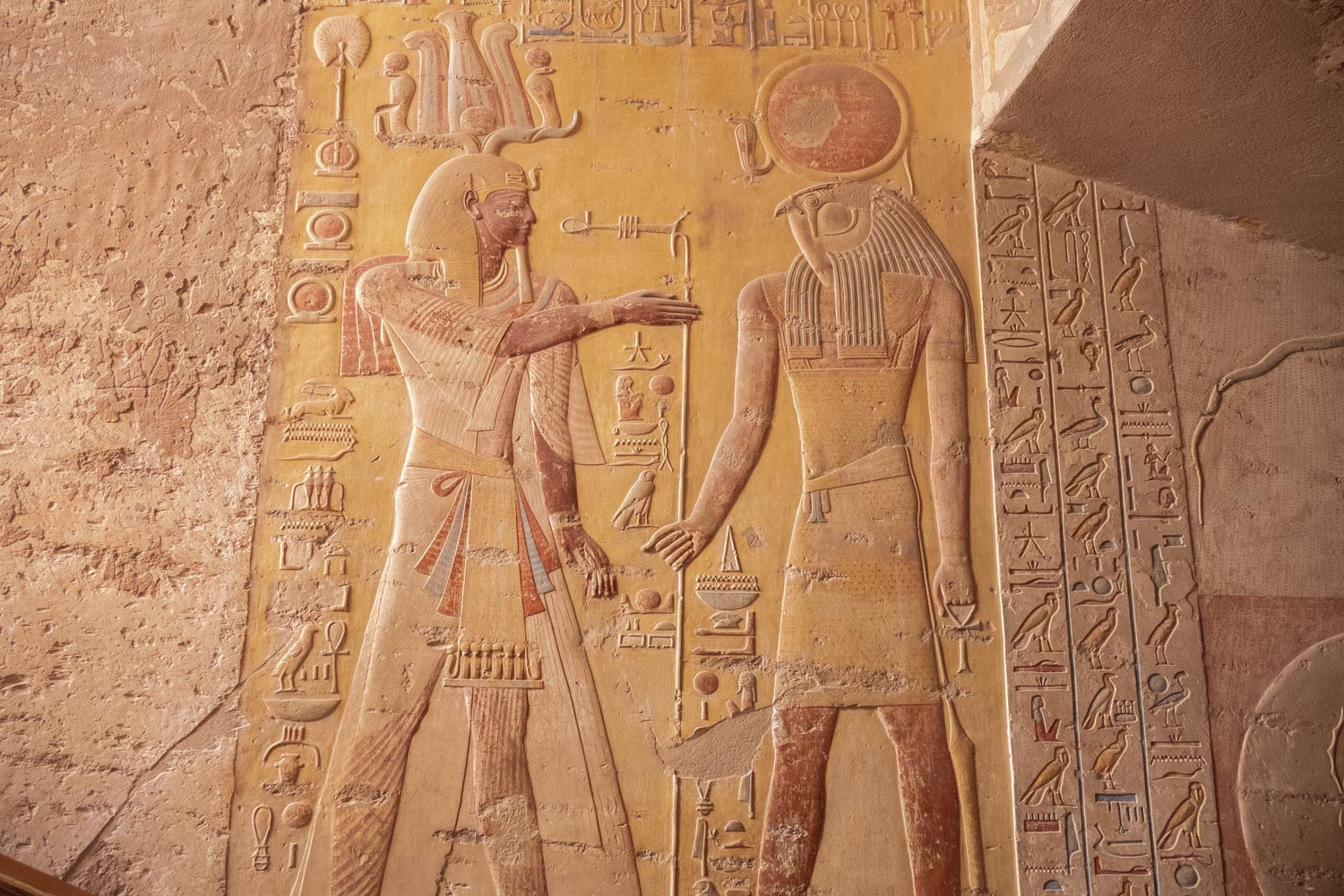

The bas-reliefs on the temple walls are even larger. The figures reach several meters in height. Many of them depict the famous show-off pharaoh Ramses II, as usual, surrounded by gods.

Among the bas-reliefs, there are not only scenes but also inscriptions in hieroglyphs. Even without knowledge of ancient Egyptian, these can be easily distinguished from regular drawings: the meaningful sequence of symbols is evident to the naked eye.

Even more hieroglyphs can be found on the walls. Interestingly, in Egypt, writing could be done from right to left, left to right, top to bottom, and even in a zigzag pattern. There were no strict rules for writing: the direction was chosen based on the surface, symmetry, convenience, and content of the inscription.

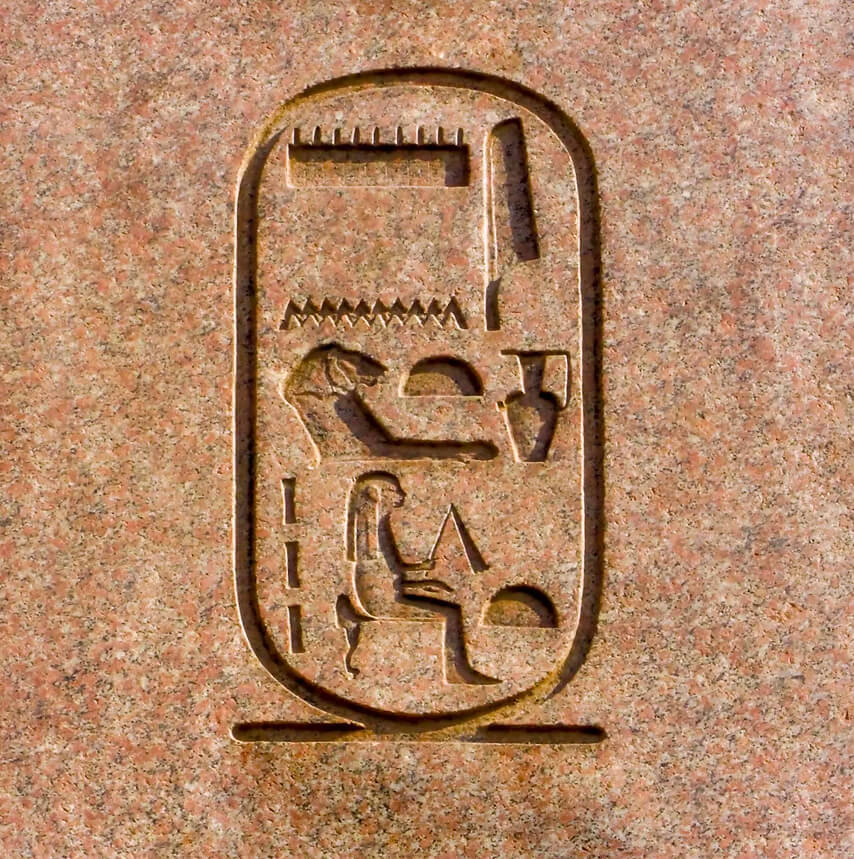

Some hieroglyphs are enclosed in an oval with a horizontal line beneath it. This framing is called a “cartouche” and indicates that the text inside is the name of a pharaoh.

Naturally, the cartouche of Ramses II appears more frequently than others. Although the temple was built seven hundred years before him, Ramses restored it and took the opportunity to inscribe his name all over it. This pharaoh was so vain that he even erased the cartouches of previous rulers — an unthinkable audacity!

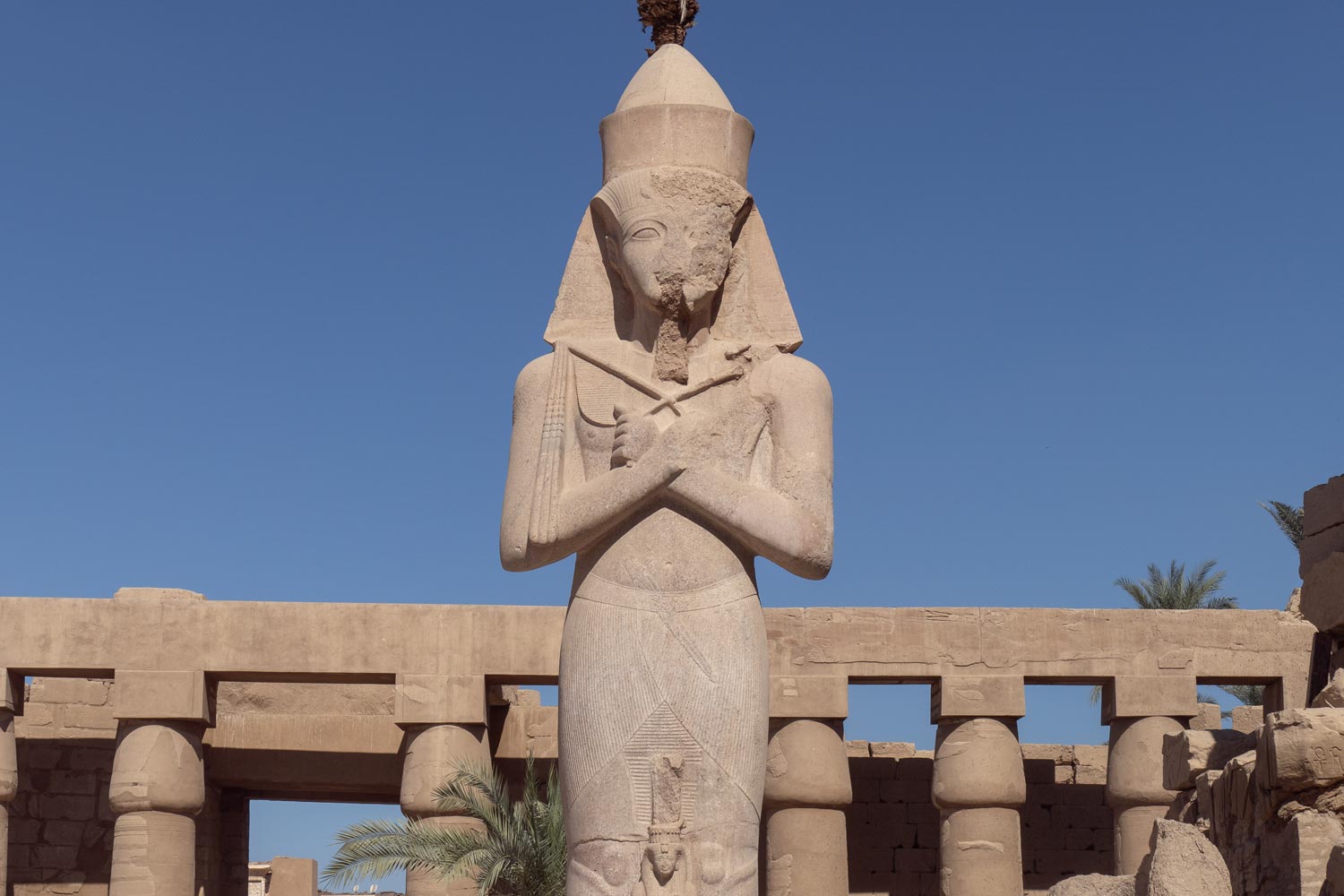

In Karnak, there are also statues of Ramses, with the largest being 12 meters tall.

In general, the only thing Ramses didn’t touch in Karnak is the obelisk of Pharaoh Hatshepsut, the largest in Egypt. Otherwise, the temple looks like the personal domain of this pharaoh.

City of the Dead

The city of the dead is visible from the city of the living. It can be reached by ferry, which transports locals and tourists across the Nile around the clock.

People also live in the city of the dead, but fewer. There are a few cafes and inexpensive hotels, but it’s hard to call it a city.

But it’s not for the hotels and cafes that people move to the western part of Luxor. Here, in the city of the dead, lies the Valley of the Kings. This is a large canyon in the local cliffs, simply filled with tombs of pharaohs and their aides. In total, 63 tombs have been discovered in the Valley of the Kings, and there may actually be even more.

There are so many tombs here that signposts are placed throughout the valley. Go left, and you’ll find Ramses. Go right, and you’ll reach Merneptah.

Interestingly, the tomb of our boastful Ramses II was flooded, and little of it remains. However, a truly magnificent tomb was given to Ramses III.

A deep tunnel leads into the tomb, with walls that seem to be made of pure gold. Of course, it’s just ordinary limestone, but skillful lighting gives it a golden glow.

The walls along the entire length of the tunnel are adorned with bas-reliefs. On one of them, for example, Ramses himself is depicted (on the left), being greeted by the gods Atum and Amun.

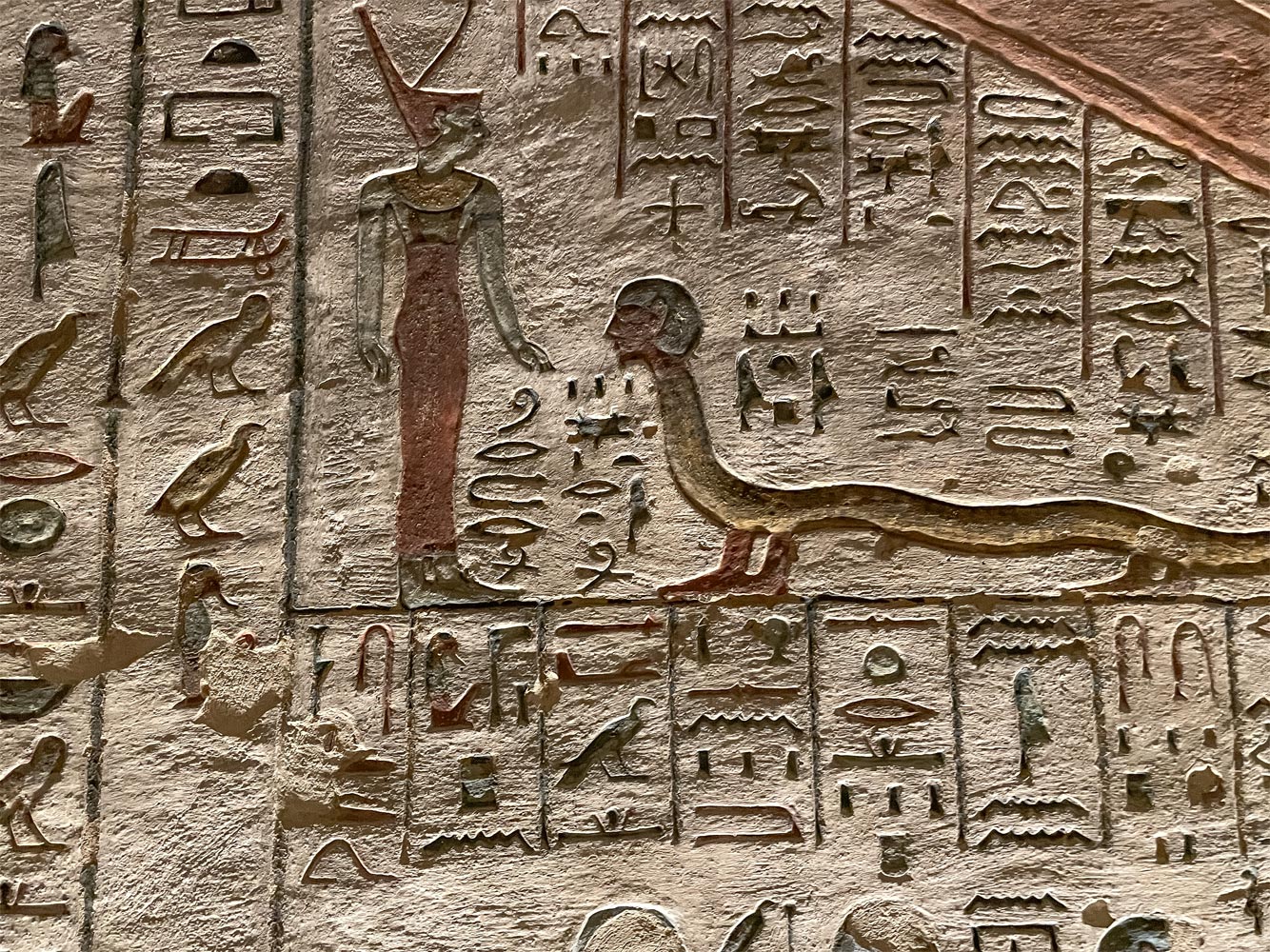

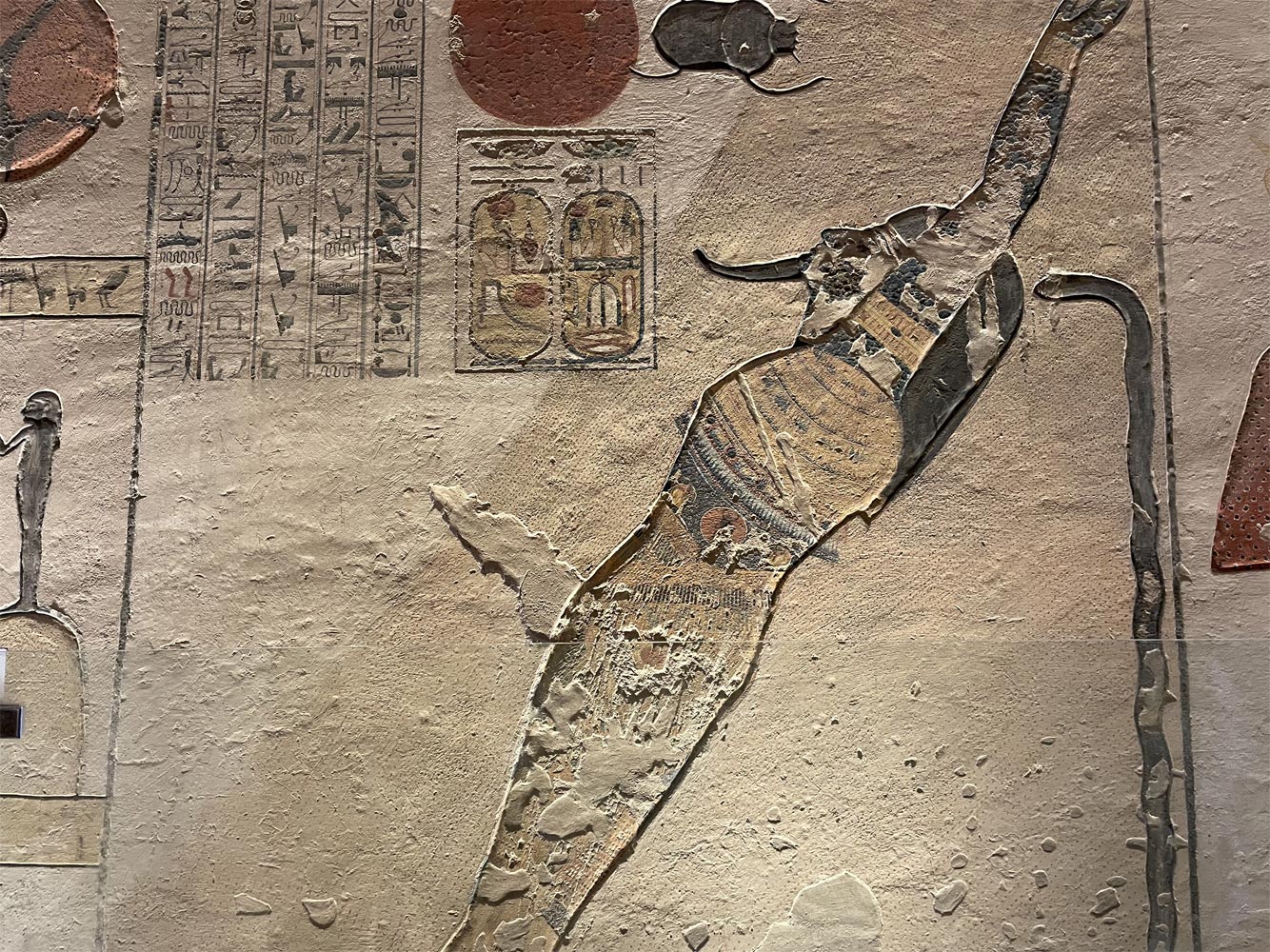

Other bas-reliefs depict religious scenes. On them, one can find snakes, Egyptian ankh crosses, falcons, scarabs, and, of course, gods: Osiris, Thoth — in short, the whole range of ancient Egyptian decor.

In addition to the drawings, the scenes are inscribed with hieroglyphs from the religious books of Ancient Egypt.

Ramses’ mummy was found in this tomb in 1886 and moved to the national museum in Cairo. The burial chamber itself, where his sarcophagus once lay, is the least interesting part of the tomb. By the time archaeologists arrived, it had long been looted. Therefore, the main treasure left from Ramses is the magnificent bas-relief depicting him alongside the god Osiris.

Another interesting tomb belongs to Pharaoh Merneptah. At the entrance to the tunnel, a beautiful bas-relief is carved on the wall, depicting this pharaoh speaking with the god Ra.

The tunnel itself is much more modest than that of Ramses.

The sarcophagus has been preserved in the burial chamber.

On the walls of the tomb, you can find similar religious scenes, hieroglyphs, and symbols. One of the most beautiful and recognizable Egyptian symbols is the scarab, which was considered a sacred beetle in Egypt.

In another tomb, belonging to Ramses IX, there is an image on the wall of the deceased pharaoh with his penis chipped away. Most likely, this was done by some Christians in an effort to combat the vulgar legacy of paganism.

Once again, the walls of the tomb are adorned with magnificent bas-reliefs, telling us about the great pharaoh and his interactions with the gods.

In this tomb, there is an absolutely incredible ceiling with numerous depictions of the sky goddess Nut.

But once again, the burial chamber turned out to be empty. The pharaoh’s mummy was found hidden near the tomb and is now also kept in the Cairo museum. However, there were, of course, no treasures found in the tomb.

In a similar manner, all the other tombs in the Valley of the Kings were investigated. They all consisted of similar tunnels leading to empty burial chambers, from which treasures were taken almost immediately after the funerals by the gravediggers and priests themselves.

As early as the 19th century, archaeologists concluded that absolutely all the tombs had been plundered. They didn’t even consider finding any treasures in them. The Valley of the Kings seemed to have been explored thoroughly, and golden masks on mummies were considered something of a legend.

However, in the early 20th century, there was an eccentric named Howard Carter. After studying the lists of discovered tombs, Carter noticed that Tutankhamun’s tomb was not among them. This seemed strange to him since Tutankhamun’s name appeared in other tombs, suggesting that he, too, should have been buried in the valley.

Carter began visiting Luxor as early as 1907, and in 1915, he moved there permanently and settled in a house near the valley.

For the next seven years, he was obsessed with finding Tutankhamun’s tomb. He was funded by the well-known English wealthy man and antiquities collector, Lord Carnarvon.

It’s unclear how Carter, not even being a professional archaeologist, convinced this lord to fund his unsuccessful searches for so many years. But eventually, the lord grew tired of tolerating Carter’s madness, who had by then become a subject of ridicule, and in 1922 he decided to stop the funding.

Carter persuaded the lord to fund one more, final excavation season. He planned to dig up an unexplored patch of land, wedged between other tombs. This piece of land was covered with construction debris and occupied by the remains of huts where the builders once lived.

In early November 1922, the archaeologists demolished the huts and, after clearing the site of debris, discovered the beginning of steps leading underground. A few days later, they found a plastered wall with well-preserved seals indicating a royal tomb. By the end of November, Carter found a cartouche containing Tutankhamun’s throne name. There was now no doubt that they had discovered an unknown tomb.

However, this still didn’t mean much: the tomb door clearly showed signs of having been opened. Initially, Carter thought that it had most likely been looted long ago, like all the other tombs. But he couldn’t just abandon the endeavor now. And then, three days later, the archaeologists found a second door, untouched and with royal seals. It became clear that something incredible lay beyond it.

Armed with an oil lamp, Carter was the first to enter the room behind the door. His diary contains an entry about how Lord Carnarvon, who had come to the excavation from London, asked him, “Do you see anything there?” to which Carter replied, “Oh yes, wonderful things!”

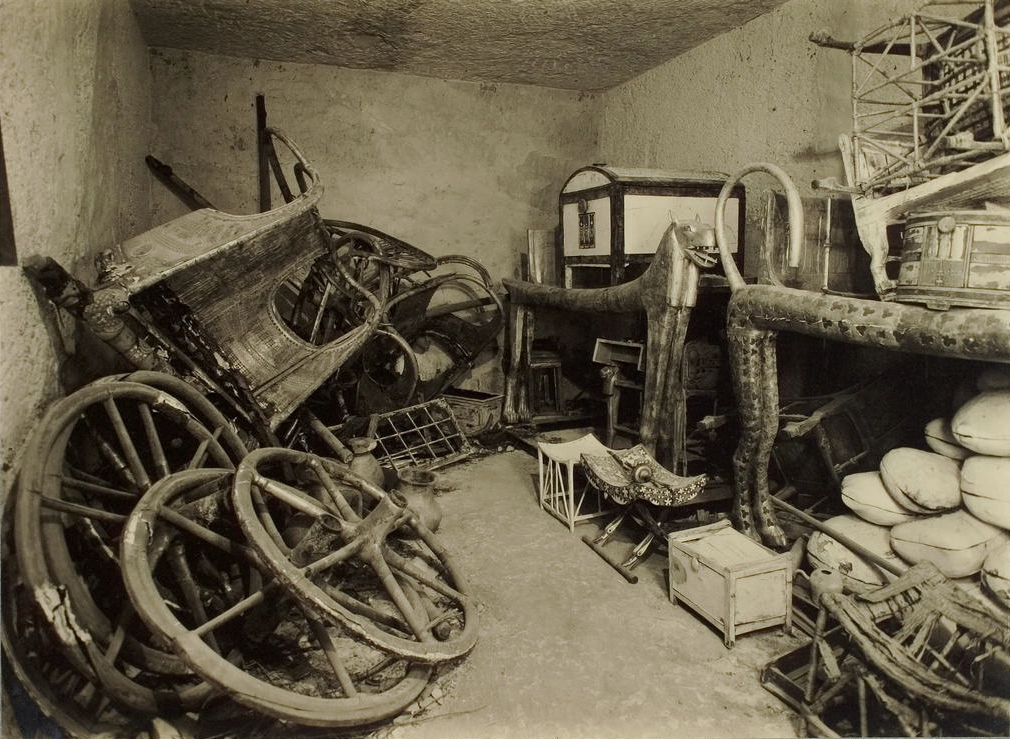

However, Carter was not referring to the kind of treasures that the reader might imagine. In the room, he saw parts of chariots, vases, a royal throne, and several chests. The fact is, even these items were considered a significant find by archaeologists since the tombs had been plundered down to their foundations.

It was not until February, after clearing the room, that the archaeologists turned their attention to the door of the burial chamber. There, they discovered treasures the likes of which no one had ever seen before. Inside lay an untouched golden sarcophagus, containing the mummy of Tutankhamun, covered with a golden mask.

In addition, the chamber contained a wooden throne covered in gold and adorned with precious stones; six royal chariots; numerous boxes with necklaces, bracelets, rings, and amulets; jewelry made of gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and carnelian; alabaster vessels and a golden chest for storing the removed organs of the mummified pharaoh; many statuettes of gods and goddesses; as well as baskets with remnants of bread and fruits, and finally, vessels with wine.

Today, Tutankhamun’s treasures are housed in the Cairo Museum. The main exhibit is, of course, the burial mask. It weighs eleven kilograms and is made of approximately 950-grade gold.

Dear reader, allow me to put it differently. You have undoubtedly heard the name Tutankhamun: today even a schoolchild knows it. But it became famous only because Howard Carter discovered his tomb.

As for Lord Carnarvon, he died in April 1923 from blood poisoning — just a few months after the tomb’s discovery. His death sparked rumors of the “Pharaohs’ curse” — the most famous urban legend in history, which remains alive today, more than a hundred years later.

Strangely, the creators of this legend weren’t confused by the fact that Howard Carter lived a happy 16 years after his discovery. However, he too fell victim, but to a different curse: unlike Tutankhamun, today very few know his name.