Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod is a very popular city, even among foreign tourists. When slightly clumsy Moscow and pseudo-European St. Petersburg become tiresome, when the decorations of Suzdal and pretentious temples of Sergiev Posad lose their appeal, tourists travel to Nizhny Novgorod to see a Russian city as it is.

Nizhny Novgorod is remarkable in that it seems stuck somewhere in the middle of eras. The city has already rid itself of the crime and devastation of the 90s, but has only just begun to enter the era of Europeanization.

They managed to plaster only a couple of streets and the main monuments, but they haven’t reached the courtyards and roads yet. A high-speed train (more precisely, a train with increased mobility) has already been launched from Moscow to Nizhny, but the city itself can hardly accommodate tourists in a decent hotel or feed them in a proper café.

In general, this place is stuck at the border of times. Not for long. Seize the moment.

Gorky Sakharov

During the times of the Soviet Union, Nizhny Novgorod was renamed to Gorky and became a closed city.

For a certain period of time, Nizhny Novgorod became a hub for defense and industrial plants. The city housed the GAZ factory, the Vympel constructor bureau, the Electromash enterprise, the Scientific Research Institute of Radio Engineering, and many other military corporations.

The factories were not given space in the historical center of the city, so the authorities began constructing them on the outskirts. The giant plants required a massive number of workers. To accommodate this, it was necessary to build a ring of endless residential areas and populate the gray new buildings with a mix of scientists, professors, engineers, and ordinary laborers.

Due to the great migration of peoples, the population of Gorky grew throughout the entire Soviet period, only to sharply decline after the collapse of the USSR.

Naturally, because the growth of any Soviet city was purely a bubble from an economic standpoint. As soon as the bubble burst, population outflow began, which has been consistently ongoing in Nizhny for the past 32 years.

As a legacy of socialism, the city was left with endless social housing that was more suitable for a correctional facility than for residential purposes. As if to confirm this, at one point, academician Andrei Sakharov was sent to one of the 14-story brick “prisons” for correctional measures.

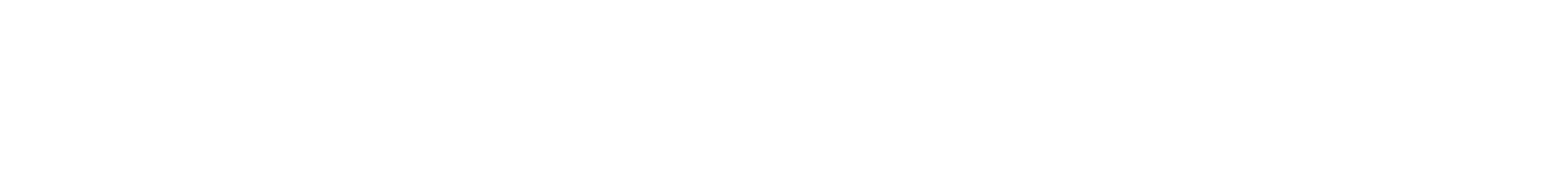

Andrei Sakharov. The greatest nuclear physicist. Creator of the world's first hydrogen bomb. Later on, he became one of the main drivers of Russia's liberation.

“He made the USSR invincible and signed its own death sentence.”

An uninitiated reader is usually taken aback when they learn about the fate of Soviet scientists. Academician Korolev, who launched the first satellite, spent six years in labor camps. Nobel laureate in physics Lev Landau spent 13 years in colonies. Geneticist Nikolai Vavilov was executed altogether.

Sakharov was luckier. He was arrested not during Stalin’s era, but under Brezhnev. By that time, the Soviet repressive machinery had already been significantly damaged, so they did not execute Sakharov or send him to exile in some remote place like Kolyma.

The security services had been pressuring Sakharov for quite some time, starting from the 1950s when he began advocating for an end to nuclear weapons testing. Later, his list of activities included human rights advocacy, publications in support of human rights, and the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Sakharov in 1975.

The final trigger for his arrest was Sakharov’s public opposition to the war in Afghanistan. It was then, in 1980, that he was sent from Moscow to Gorky, placed in a ground-floor apartment, and placed under surveillance. Is it a lenient punishment, one might ask? Compared to execution, indeed, it is lenient. “Grandpa Lenin was kind. He could have been harsher.”

Nowadays, the apartment has been turned into a museum. The bus stop is even named “Sakharov Museum.” There is a sign on the building indicating its significance.

The entrance is directly through the common corridor, just as one would typically enter an apartment.

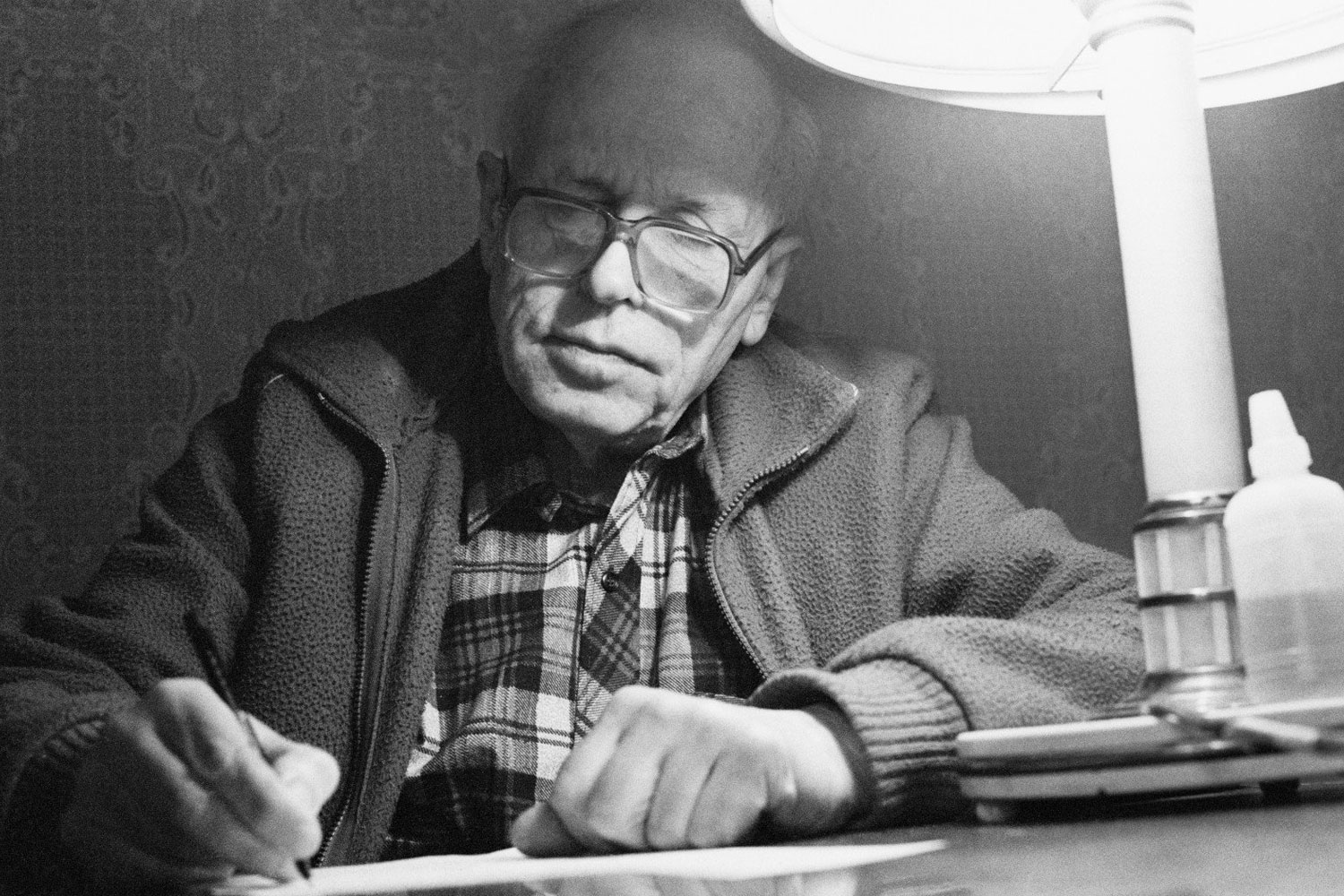

In the vestibule, newspaper clippings and banners are hung on display.

The apartment is a preserved Soviet Union, hardly touched since the 1980s. Not all elements of the interior are original to Sakharov. Some similar items had to be purchased from flea markets.

In general, Sakharov’s apartment looks the same as it did during exile. It seems that even the wallpaper and laminate have been found and reinstalled.

Kitchen.

Bedroom. An illustrative guide to the life of people in the USSR. During those times, an average apartment looked exactly like this.

A round-the-clock security guard was assigned to Sakharov during his exile. In front of the entrance to the apartment, a police officer stood on duty around the clock, sitting on a stool by the door. It seems that entering or leaving the apartment was possible without permission from the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, but Sakharov was constantly under surveillance.

In the opposite building, right in front of Sakharov’s apartment windows, a KGB post was located. Continuous surveillance of the apartment was conducted through the window, so Sakharov communicated with his wife in writing and using gestures on important matters.

In one of the rooms of the apartment presented to Sakharov as a hotel, there was a sign that read “Administration.” The room itself was always closed.

During exile, an elaborate psychological pressure was imposed on the exiled academic. As the museum guide assures, they attempted to drive him insane and push him to a nervous breakdown through a series of petty harassments that were disguised as coincidences.

For example, Sakharov went out to make a phone call (there was no telephone at home). And the nearest telephone was broken — the cable was cut. The academic returns to his car to drive to another telephone. But the tire of the car is punctured.

Nowadays, you can just call an auto repair service, and everything will be quickly fixed. But back then, it was a whole ordeal: you had to walk to the workshop, make an appointment for a week or two in advance, then the mechanics would come, take the car away, and return it after another week.

And yet, let’s say he managed to walk to the telephone. He made the call. He returns home, and then the player doesn’t work. He takes it apart — a part is missing. Where could it have gone? He goes to the bathroom — the toothbrush is gone. “Did you take it, wife?” “No, not me. It’s the house spirit.” After a week, the part and the toothbrush were returned to their place.

These were precisely the petty tactics used by the KGB as part of their harassment methods during the late Soviet era. They were no longer capable of directly targeting a world-renowned scientist, so they resorted to petty acts of sabotage. These constant trivialities, absurdly funny, gradually begin to drive one to madness. And the main thing is that nothing can be proven — everything can be dismissed as mere coincidence.

Later, Sakharov devised a plan. Pretending to leave home for an extended period, he abruptly returned to the apartment. The administrator’s room turned out to be open, and there was a person inside the apartment. It turned out that the window grille was being opened from the outside. An agent would climb into the room, open the door, and gain access to the apartment. That’s how all the correspondence was being read, and that’s where the toothbrushes were disappearing to.

The scientist’s exile lasted for 6 years. Sakharov was released from his bitter confinement in 1986, and it was none other than Mikhail Gorbachev who did so. Now a boulevard in Moscow is named after the academic, but Gorbachev has yet to receive a monument for dismantling the accursed prison of nations.

City

Nizhny Novgorod begins with the “Marins Park” hotel, built on the site of the former “Central” hotel. In the same Soviet building, with the same Lenin statue in the square.

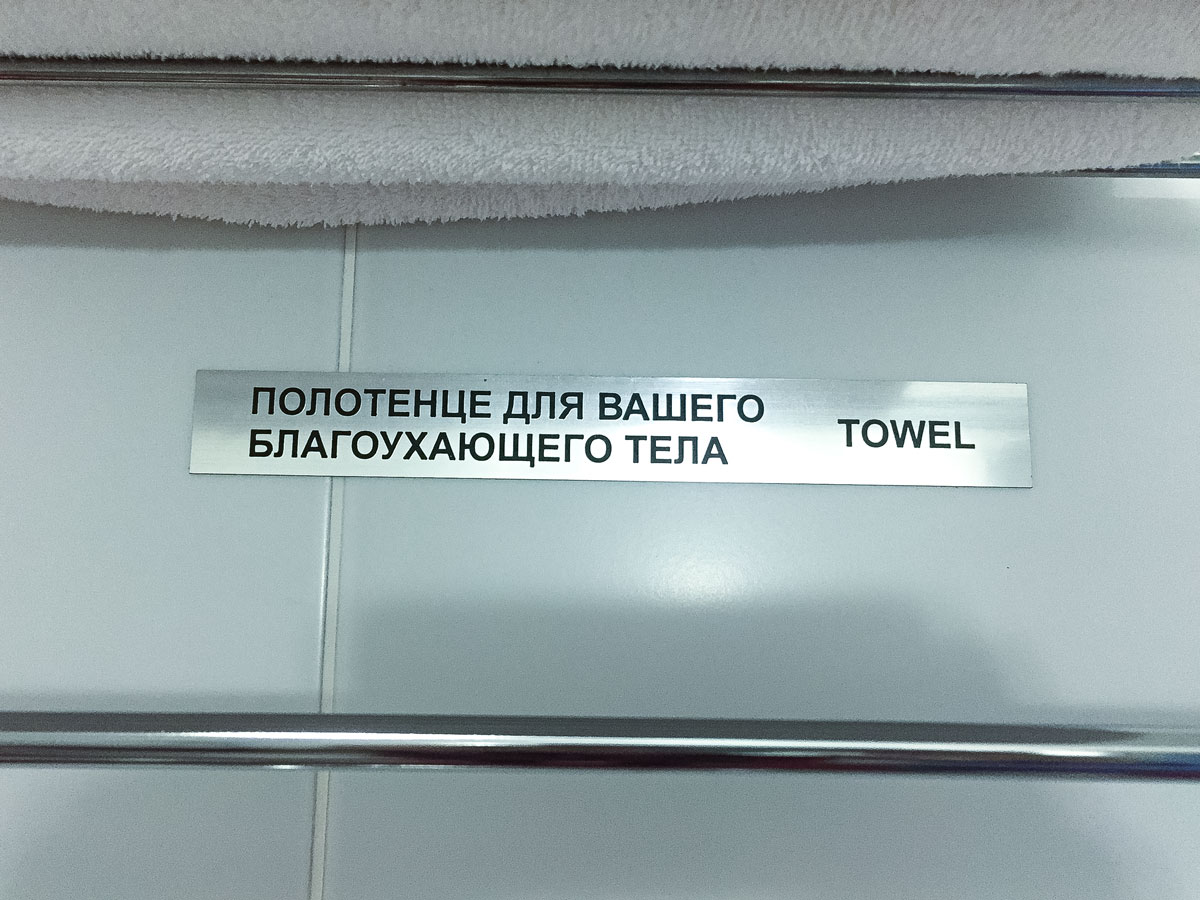

The rooms are filled with madness: the owners of the small hotel turned out to be a bit debilish and labeled all the items in the room.

The entire Nizhny Novgorod is arranged in a similar manner. Rare glimpses of goodness are wrapped in aging dilapidation and provincial absurdity.

The best-restored building is the State Bank, which was built back in 1913. It features a pseudo-Russian style, similar to the GUM department store. It’s a magnificent building. The Soviet coat of arms sits atop, while the facade bears imperial symbols. It’s a delight.

In the city, you can find a couple more interesting houses that can be counted on one hand.

There is only one nice street in Nizhny Novgorod: half of Bolshaya Pokrovskaya and half of Rozhdestvenskaya. Even in the city center, one cannot escape the feeling of provinciality.

Nizhny Novgorod residents timidly try to recreate something historical, but it turns out weakly. Here’s a pre-revolutionary sign. The fonts and inscriptions are done well, with only one mistake. But the building it hangs on is just a shed, not a workshop.

And of course, in Nizhny Novgorod, there is a popular accessible pastime. It’s called “turn into an alley.” The essence of the game is to turn into an alley without fainting.

Attempts to design a hipster-style interior in this cafe even look like a mountain of clutter.

The streets of Nizhny Novgorod are in a terrible condition. Officially, they are pedestrian with tiled pavement. But even the tourist sidewalks are in a horrible state, as if there was a German bombardment just yesterday.

Nizhny Novgorod is one of those cities where they haven’t even started restoration and the fight for a pedestrian-friendly city. Here’s a perfect example of a typical Nizhny Novgorod street. At the first rain, water floods not only the sidewalk but also floods the basement floor.

What can be said about residential areas — existential Russian chaos reigns in the courtyards.

We will call this architectural style “Freestyle.”

The only entertainment for a photographer within the “Freestyle” framework is capturing compositions of weathered walls and a tangle of electrical wires through the lens.

Look at how beautifully you can even capture a posterior.

Indeed, in Nizhny Novgorod, there is a difficult-to-capture posterior that no lens can capture well.

The Nizhny Novgorod devastation is compounded by construction absurdity. Sometimes it’s impossible to look at the city without laughter. “World Trade Center,” yeah.

The drawing of a soldier with the caption “Let these ruins be the Reichstag” can be interpreted as if Nizhny Novgorod itself is the Reichstag.

Satisfied with the ruins of the Reichstag!

But there is real history in Nizhny Novgorod as well. This 19th-century wooden architecture is of stunning beauty.

Did I say there “is” real history? Perhaps it’s more accurate to say “was.” These shots were taken in the summer of 2017. I’m not sure if this house still stands. Even back then, it was in a terrible condition. Maybe it has been demolished.

These houses were definitely demolished. Even back then, they were surrounded by panel buildings.

The saddest part of this story is the residents’ desire to quickly leave the decaying ornate house and move into a cozy concrete container on the 17th floor.

You can understand the people living in these hovels. They are given a choice between two evils: to stay in an old ruin or move to a panel prison. Few consider that there is a third way, the path chosen by Europe: lovingly restore the historical buildings.

And even if someone considers such a path, no authority in modern Russia would allow them to pursue it. What is more profitable per unit of area: a wooden house for one family or a concrete one for 300 families?

It is impossible to halt the construction. That is why the history of Nizhny Novgorod is simply being erased forever.

I feel sorry for Nizhny Novgorod. This city should be incredibly beautiful, as it is built on elevation changes. The city has plenty of steep bridges, staircases, ascents, and descents.

The most iconic place in Nizhny Novgorod is the Chkalovskaya staircase.

The longest staircase in Russia, consisting of 560 steps, leads from the Chkalov Monument down to the waterfront.

The construction of the staircase began in 1943 when Gorky was being rebuilt after German air raids. Six years later, a monument of Stalinist grandeur emerged, with an incredibly steep staircase.

The staircase was dedicated to the victory in the Battle of Stalingrad. 7 million rubles were spent on its construction, and, of course, the chairman of the city executive committee was arrested for embezzlement of public funds. How else could it be!

But in this case, the money was not spent in vain — the staircase turned out to be incredibly steep. Nowadays, it attracts pilgrims from all over the world, and races are organized on it.

The liveliest part of the embankment begins from the staircase. Nizhny Novgorod is situated on the Volga. The city’s waterfront is quite neglected, but even the dilapidation cannot spoil the impression.

The best place in Nizhny Novgorod is the riverside. The best event in the city is the sunset.

For such views, Gorky can be forgiven for everything.

The renovation of Nizhny Novgorod is just beginning to kick off, and the city has the potential to become one of the most beautiful cities in Russia. After all, fixing streets and buildings is a minor issue. Sooner or later, they will be reached and repaired.

The main factors of success in Nizhny Novgorod are two: the complex, hilly terrain and the Volga River with its incredible sunsets. This is priceless.

And for everything else, there is a master plan.