Touristic Armenia

Armenia is a very small country. The total area of the country is only 30 thousand square kilometers. The area of Moscow Oblast is 45 thousand square kilometers.

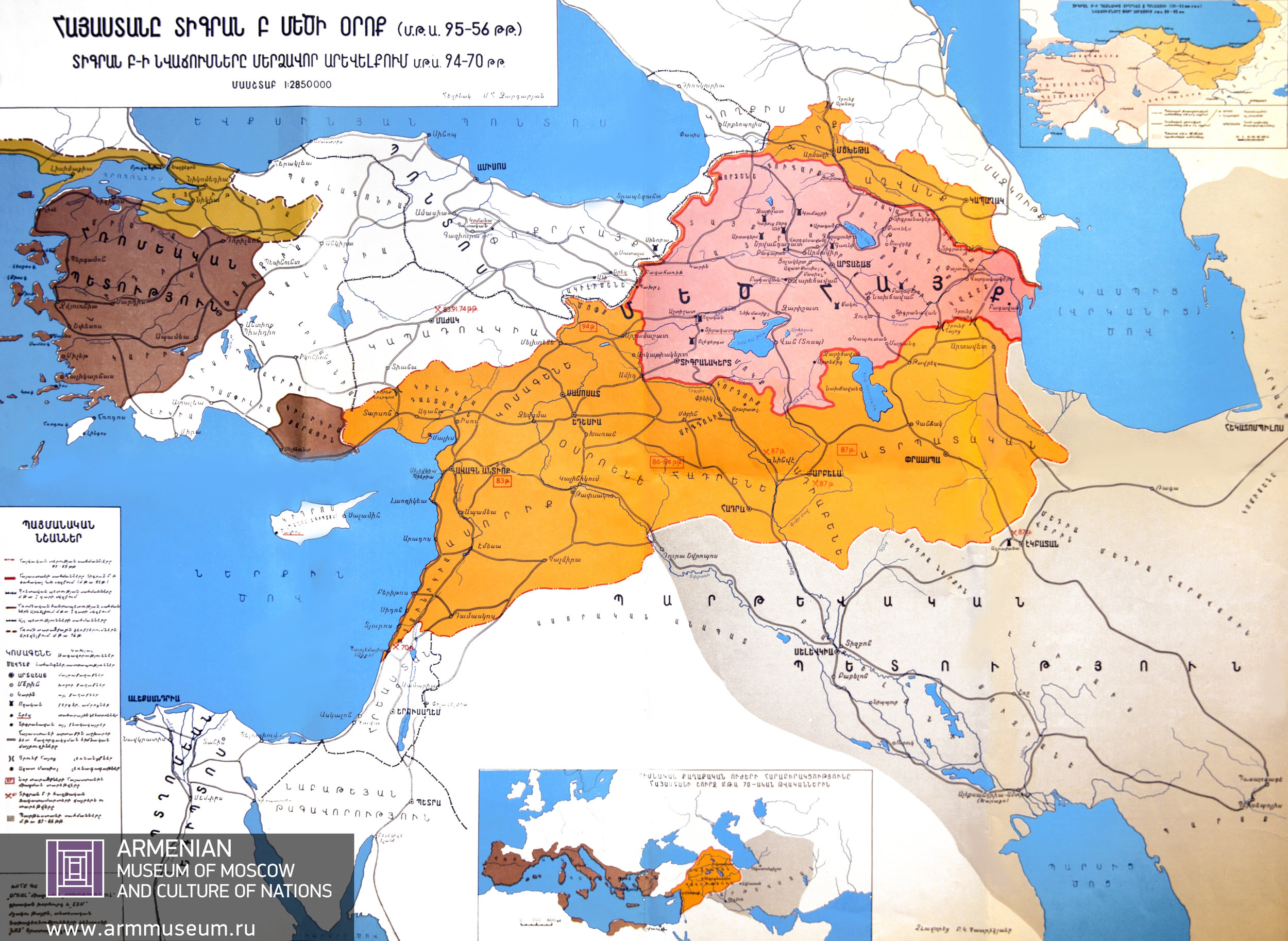

Once everything was completely different. Long ago, from the -4th to the 5th century, the Armenian Empire existed, or as it is often called, Greater Armenia. During its heyday under King Tigranes II, the Armenian state briefly became the world’s strongest empire. The borders of the Armenian Empire reached as far as the Jordan River. Tigranes' Armenia and its sphere of influence included parts of Iran, almost all of Syria, Palestine, and Israel, a decent chunk of Turkey, and the entire territory of the South Caucasus.

Under Tigranes II, the Armenian Empire grew to an unimaginable size of 1 million square kilometers. Rome pressed on Armenia from the west, and Parthia from the south. The Great Armenia that flared up on the world map within the borders of Tigranes II lasted only 30 years before disappearing. The first losses of conquered lands began under Tigranes himself. The subsequent rulers lost influence even faster, until in 387, Iran and Rome divided Armenia into two parts.

Since then, Armenia has hardly been fully independent. At different times, the country was under the control of the Roman Empire, Persia, Byzantium, the Arab Caliphate, Mongolia, Turkey, the Russian Empire, and the USSR. Today’s independence of Armenia has lasted a microscopic amount of time compared to its insanely long history. Of course, Armenians regret the lost grandeur. Even a map of the former empire was found at one subway station.

Today’s Armenia is a third smaller than the Moscow District. That is, some residents of the Moscow suburbs spend more time commuting to work than Armenians traveling from one end of the country to the other. Therefore, it is easy to see the whole country in just a few days. To do this, you just need to find a good taxi driver and arrange a national tour with them.

So that’s what I did. A taxi driver named Serian Petrosyan drove me around the country for two days and even invited me to his home for lunch. The tour cost me only six thousand rubles. And I met him in Ejmiatsin.

Etchmiadzin

Echmiadzin is the main monastery of the entire Armenian Church.

It is located in the city of Vagharshapat, 20 kilometers from the center of Yerevan. This is the most popular attraction in Armenia, and tourists come here in droves. The monastery is included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

The tour begins with a round church standing right at the entrance to Echmiadzin. It seems as if this church was built in ancient times by some familiar architect of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In fact, it was built by a local philanthropist in 2007.

Much more interesting is the seminary building from 1874. This is where Armenian priests are trained.

In the monastery courtyard stands an ancient stone cross dating back to 1563. Such crosses are called “khachkar.” In Armenian, “khach” means “cross,” and “kar” means “stone.” The etymology of the word “khach,” which in Russia is used to refer to migrants from all southern republics, is precisely traced here.

Right behind the cross is a well-kept monastery garden, at the end of which stands the Echmiadzin Cathedral.

The cathedral turned out to be closed for repairs. Good timing: during the pandemic, there are few tourists. But what am I supposed to do?

The cathedral was built by the Armenian king named Tiridates III. The construction of Echmiadzin began in 303, just as Armenia accepted Christianity — the first country to do so. The Echmiadzin Cathedral is one of the oldest Christian cathedrals in the world.

As in any similar cathedral, there are Christian relics stored in Echmiadzin. In addition to a piece of Noah’s Ark and someone’s relics, Echmiadzin houses the spear that supposedly pierced Jesus Christ during his crucifixion on the cross.

After the baptism of Armenia, its baptizer, Gregory, settled in the monastery. A luxurious residence was built for him. Today, the residence of the current Patriarch of Armenia is located on the territory of the monastery. It is not possible to enter it, but you can see it through the fence.

The monastery is otherwise completely uninteresting unless the reader is studying the history of the Armenian Church. There is absolutely nothing to do here. There are some ancient crosses standing.

Ancient arches are standing.

Ancient air is cooled by ancient air conditioners in ancient cells.

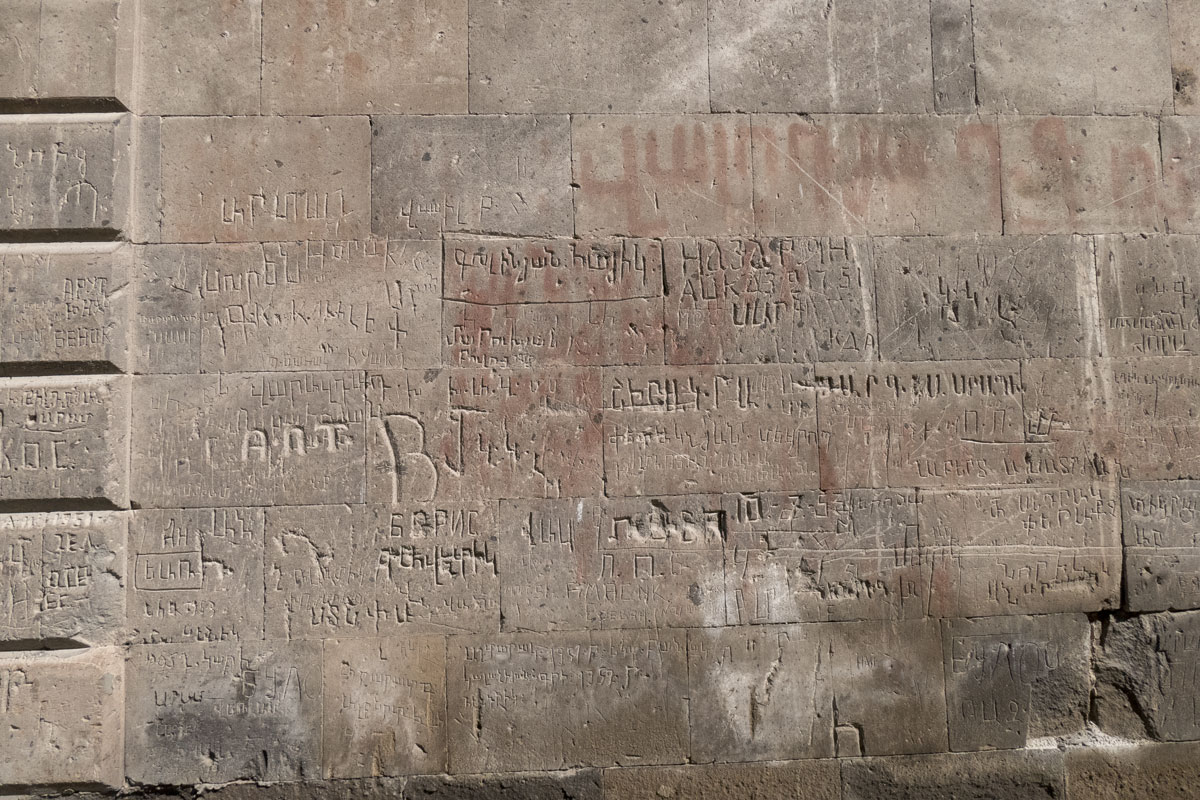

Ancient inscriptions “Here was Nazaryan” gaze upon the visitor from ancient walls.

As often happens with popular spots, Etchmiadzin is a completely commercial and bland phenomenon. There are much more interesting places in Armenia.

From Etchmiadzin, it’s easy to get to a village called Khor Virap, where you can get a good view of Mount Ararat. The easiest way to get there is by taxi. The trip takes about 40 minutes and will cost less than a thousand rubles.

“My name is Seryan,” introduced the Yandex taxi driver, “And yours?”

“Andrey.”

Serian turned out to be a plump, tanned, almost completely gray-haired, good-natured Armenian-looking man in his fifties with a smiling face. The conversation with Serian started immediately and gradually flowed from one trip to the next, and then into a whole journey across Armenia.

“Andrey, where are you going after Khor Virap?”

“I wanted to go to Garni and Geghard.”

“Andrey, let’s make a deal. I will take you there. Just tell me the cost right away.”

“Alright. Seryan, have you been to Khor Virap?”

“I have, a long time ago. It’s an old monastery. There’s a pit there where they threw Gregory. The king wanted to kill him. Kept him in that pit. Comes back after 13 years, and that bastard still hasn’t died!”

With these words, Serian burst into such a hearty laughter that I almost choked on my own laughter. After a minute, he stopped laughing, wiped away a tear, and added, “And then Gregor climbed out of the pit and baptized Armenia!” — and again howled with laughter so much that he could barely hold the wheel. Regaining his composure, Serian continued, which finally finished me off:

“By the way, my surname is Petrosyan. Seryan Petrosyan. Andrey-jan, do you like Petrosyan?”

“Madly. But I still love Martirosyan more.”

“We all love Martirosyan in Armenia. He has achieved a lot. That’s what I think! Andrey-jan, where are you from?”

“Krasnogorsk. Moscow District.”

“I’ve been there, in Krasnogorsk. Such a nice place, jan. I ask everyone: where do you want to live, jan? Everyone answers: I want to live in Krasnogorsk.”

It was impossible to tell if Serian was joking or being serious. It seemed that I had encountered the phenomenon of Armenian humor. Serian spoke so stereotypically that it seemed like he had just come back from filming “Mimino”.

“Andrey-jan, once I worked in Sochi. I go into a Georgian restaurant, there a Georgian meets me: ‘Hey, come in, sit down, dear Seryan, genatsvale’. I sit down, he brings me a menu and says: ‘Seryan, genatsvale, Armenian cuisine takes the first place in the world! And do you know what cuisine is in second place?’. I say: ‘Could it be Georgian?’. He replies: ’‘No, it’s Chinese!’”

“Seryan, this is brilliant. Just like in ‘Mimino’.”

“My wife tells me I look like Frunzik. That’s what I think.”

Hor Virap

The atmosphere of Armenia was shrouded in haze. Clear weather is rare here, mostly in winter when it’s not so hot. As we approached Khor Virap, the silhouette of a mountain began to emerge through the haze.

“Seryan, is that Ararat?”

“Where? I don’t see. I've become completely blind.”

“It should be visible from Khor Virap, right?”

“Yes, it’s the closest. Ararat itself is now in Turkey. What an injustice! You know, Andrey-jan, once Turkey said we should remove Ararat from our coat of arms. The Soviet ambassador objected: ‘Then you should remove the moon from your flag’.”

“Amazing.”

“Yes, it’s unfair. Once I stood very close to Ararat. And I was scared. Very much. It’s somewhat ominous. That’s what I think.”

The mountain that appeared to me as Ararat gradually began to stand out from the general landscape. It had a strange background, slightly darker than the rest of the sky. This background occupied half of the sky and became increasingly dark.

When two distinctive breaks finally appeared on the edge of the background, I realized that it was not a background at all. It was Ararat. The mountain that I initially thought was Ararat turned out to be just a pile of garbage in some quarry.

Khor Virap is an exceptional place in Armenia.

This is an ancient monastery, the first chapel of which was built in 642 AD. Before that, an underground prison stood on the site of the monastery. The prison must have been much older than the monastery and existed several centuries before its construction.

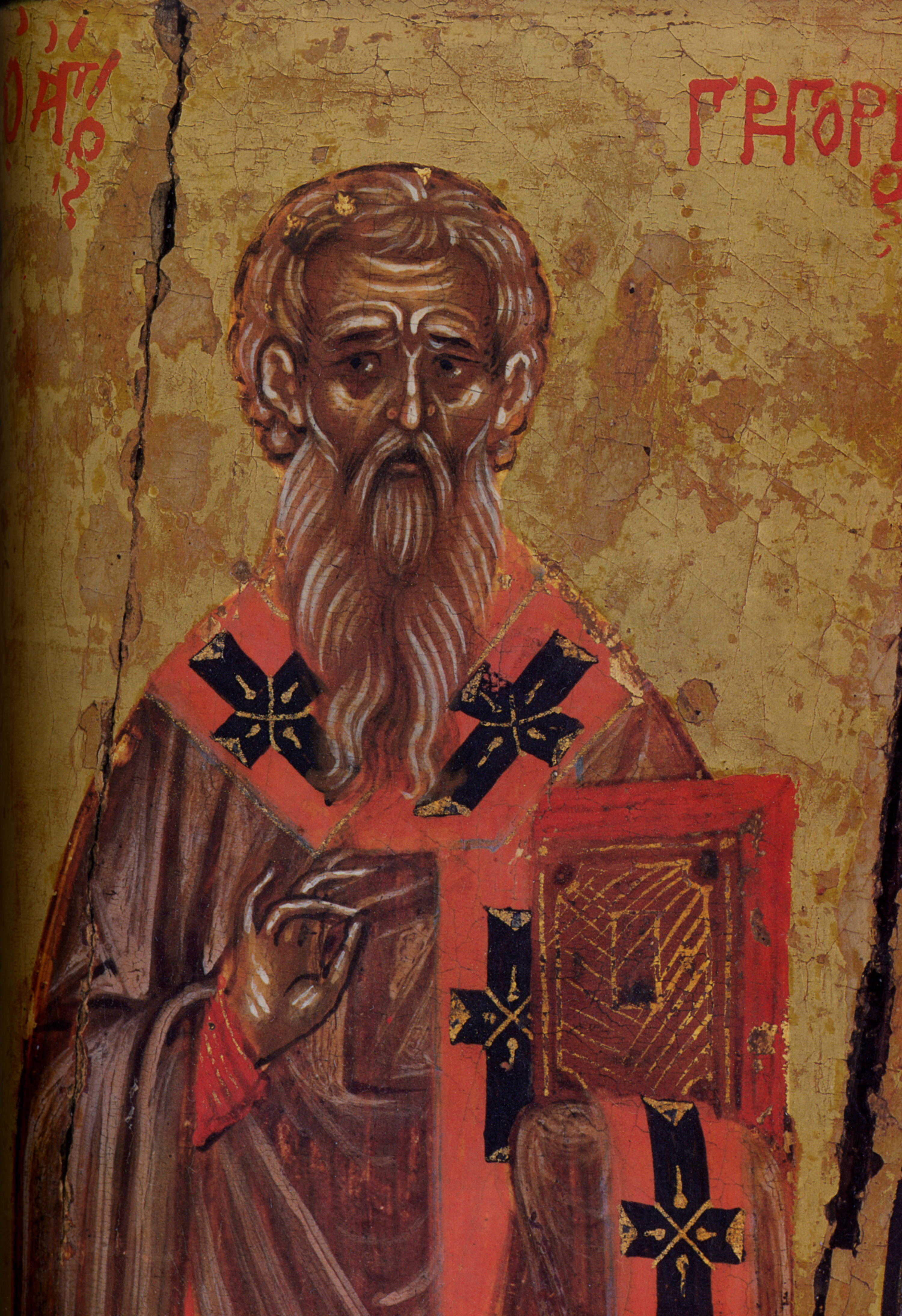

Khor Virap is famous for the fact that it was in its underground prison that Gregory the Illuminator was thrown — the same person who converted Armenia to Christianity and became its first patriarch.

Although Christianity had existed in Armenia for almost two centuries by that time, it was a religious sect and the domain of a few preachers. A supporter of this sect, who presented himself as Gregory, gained great popularity.

Now he is known under various aliases: Grigor Lusavorich or Gregorios the Illuminator. These are all translations of the same word. The alias “Lusavorich” is derived from the Armenian root “lus”, while “Fostir” is from the Greek root “phos”. Both words mean “light”. Therefore, the Russian alias — Gregory the Illuminator — is only a loan translation from Greek or Armenian. The real name of this person is unknown.

However, there is a plausible legend associated with his activities.

The popularity of Gregory was significant enough for the King of Armenia, Trdat III, to begin to fight against him. According to one version, Gregory refused to perform the rite of sacrifice during a pagan service conducted by the king. Trdat declared Gregory to be the son of his father’s killer, King Khosrov II. Under this pretext, Gregory was placed in the underground prison of Khor Virap. At the same time, mass persecution of members of the Christian sect began in Armenia.

Gregory spent about 14 years in prison. According to legend, King Trdat wanted to marry a girl named Ripsime, who together with her companions had fled to Armenia because of the harassment of the Roman Emperor Diocletian. Ripsime rejected Trdat and was executed along with her friends — a total of 33 people.

However, Trdat turned into a boar under unclear circumstances.

Most likely, the transformation into a boar in the story of the Armenian historian Agafangel was described as some kind of mental illness. It was probably zoanthropy — a disorder in which a person believes that they can transform into an animal.

Usually, a wolf is chosen as the animal, and legends about werewolves are attributed to this disorder. However, clinical practice has described “transformations” not only into wolves but also into hyenas, cats, horses, tigers, birds, frogs, and even bees. So, Trdat’s insanity was most likely an acute episode of zoanthropy against the background of schizophrenia or another chronic mental illness.

Trdat decided to seek treatment from Grigory. Strangely, the symptoms of zoanthropy disappeared. Perhaps it was a coincidence. It is even more likely that Trdat developed serious paranoia because he had imprisoned a potential saint. Paranoia could have simply passed due to Grigory’s release.

Anyway, after Trdat’s healing from zoanthropy, the king decided that the whole country was suffering from schizophrenia and decided to baptize Armenia and make Grigory the first Armenian patriarch.

The baptism took place in the year 301. Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity at the state level. Now, persecutions of pagans began, with even greater zeal than the repression of Christians.

Well, in the place of the former underground prison, the first chapel was built in 642. Later, the chapel was rebuilt many times, other buildings were added to it until a small monastery was formed.

The Choir of Virap is located right on the border of Armenia, just over a kilometer away from Turkey. Against the backdrop of the monastery, the silhouette of Mount Ararat can be barely seen.

To see Ararat in all its glory is a rare stroke of luck. More often than not, the atmosphere is obscured by haze. When the air is crystal clear, the Choir of Virap looks like this:

In the center of the monastery, there is a church from the mid-17th century.

The church is stunningly beautiful. Sunlight enters through a small window. Due to the smoke from the candles, a light cone burns in the air, which looks like a divine miracle against the backdrop of icons and frescoes.

The chapel, built on top of the underground prison, has also been preserved. Inside it, to the right of the altar, there is a hole in the wall that leads to the underground prison.

The stairs go down to a depth of about 6 meters. On the ground, there is a circular room — a solitary cell. A church chandelier hangs from the ceiling, and a large icon with Grigory is on the wall.

I left the Choir of Virap and got into Serian taxi. The road from the Choir of Virap to Garni takes an hour and goes through absolutely incredible places. Central Armenia is reminiscent of Palestine, with its winding roads between mountains, sparse vegetation, and incredible heat.

Garni

Garni is an ancient pagan temple, built by King Trdat the First in 77 AD. Even on approach to the site, it is evident that the temple strongly resembles Greek architecture.

The Greek style is no coincidence. Garni was built during the period of the flourishing of Hellenism in Armenia. If Hellenism had already ended in the Mediterranean before the birth of Christ, it lasted another three centuries in our era in Armenia.

Garni is a stunning place. It’s hard to believe that this is Armenia. Pure Greece.

In 1679, an earthquake destroyed the original temple. It was restored from ruins during Soviet times. One could say that it is the original.

Geghard.

“Seryan, how are things in Armenia now? Are you having a crisis?”

“Andrey-jan, things are very bad here. Yes, it’s a crisis. Everyone is leaving the country, there’s nothing to do here. There are no jobs. We lost the war, you've heard, right? They took Karabakh from us, we didn't even have time to blink. The dog Pashinyan screwed everything up.”

“I've heard he’s a good president, isn’t that true?”

“How can he be good? He came from the streets, who is he, a journalist. How can he be a prime minister, Andrey-jan? He doesn’t understand anything.”

“Yes, you indeed lost Karabakh very quickly. Many people died in that war.”

“Many people died, but for what? To give everything back? You see, Andrey-jan, Azerbaijan, they’re Turks. The Ottoman Empire. Erdogan has the strongest army in the world, only Russia, China, and the USA are stronger. Azerbaijan is financed by Turkey, they wouldn’t be able to do anything on their own. Now what? They took Karabakh, there’s a wedge between Karabakh and Nakhichevan. There could be a war.”

“What do you mean by ‘wedge’, Seryan?”

“Andrey-jan, open the map and look. Nakhichevan is on the left, Karabakh on the right. The Syunik region of Armenia is between them. What will Turkey do next? They will try to take this region to connect Nakhichevan and Karabakh. You see, Erdogan wants to restore the Ottoman Empire. What’s beyond the sea? Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan. Armenia is an obstacle, this little wedge — it’s like a thorn for Erdogan. That’s what I think.”

Quite close to Garni is the old Armenian monastery of Geghard, which is on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. Despite the similarity in names and territorial proximity, there is nothing in common between Garni and Geghard. Geghard is not a pagan but a Christian temple.

According to legend, the first version of Geghard was built in the 4th century by Grigory, the baptizer of Armenia. Then, in the 9th century, it was destroyed by Arabs. After the fall of the Arab Caliphate, the temple began to be restored. The current church was built in 1215.

Gerard is in the mountains. You can tell from afar that you’re approaching a monastery. It can be seen by the large metal crosses hammered into the surrounding rocks and shining in the sun.

The church is under reconstruction.

There are animal reliefs on the walls.

Entrance to the church.

Inside, it’s just a complete pile of rubble. Geghard is some kind of mixture of a Christian church and pagan sanctuaries in the mountains.

The only place in the world where I saw something similar is the temple complex of Angkor Wat, which was used as a filming location for “Lara Croft.”

On the one hand, there is no prohibition on depicting animals in churches in Christianity. On the other hand, it feels like being transported to ancient Babylon.

There are plenty of crosses on the walls as well.

Not all tourists notice a small staircase — it is located at the exit of the church. If you climb it, you can go to the second floor of the temple. Here there is a large spacious room with an open dome.

Crosses and inscriptions in Old Armenian are carved on the columns.

There is a small cave church in the nearby rock. Inside is a modest altar. There are also cave cells where monks used to live. Initially, Geghard was called “Ayrivank,” which means “cave monastery” in translation.

The name “Geghard” comes from the Old Armenian word for “spear.” According to legend, the spear that pierced Jesus Christ during his crucifixion was kept here.

Nowadays, the unique spear is located in another Armenian monastery, Etchmiadzin. Another one is located in the Vatican. The third one is kept in the Vienna Palace. The fourth one... well, you get the idea.

Sevan

I thought that the journey with Serian would end in Geghard. The next stop on the way was Yerevan. Suddenly, Serian made me an offer that I couldn’t refuse. As always, in the best traditions of “Mimino”.

“Andrey-jan, do you like dolma?”

“Of course, I love it.”

“Andrey-jan, do you want me to call my wife now and we go to my house to eat dolma?”

“Of course, I’d love to!”

“You just tell me, today or tomorrow? Do you want to go somewhere else?”

“Tomorrow I wanted to go to Dilijan. On the way, I wanted to stop by Sevan. And then there is a village called Fioletovo, where Molokans live.”

“Do you want to visit the Molokans? It will be on our way. Let me take you to Sevan tomorrow, then to Dilijan, then to the Molokans, and then you can eat dolma at my place? I live in Vanadzor. It’s a city.”

“With pleasure, Seryan! How much will it cost?”

“Andrey-jan, you think about it and tell me yourself. Because in Garni, I told you, and it turned out to be not enough. You look on the internet, how much it usually costs. But you make sure to look well.”

The next day, Serian picked me up from the hotel, and our journey continued from Yerevan. On the way to Dilijan, there is Lake Sevan and the city of the same name adjacent to it. Sevan is the largest lake in the Caucasus.

There is a small peninsula near the lake with the remains of an old monastery. This church was built in 874.

And this one was built in 305. Such dates are commonplace for Armenia.

Sevan is the most popular tourist destination in Armenia. However, there isn’t much sense in staying here for too long. Across the mountain range lies the city of Dilijan, in whose forests several ancient monasteries are located.

Djukhtakvank

Jukhtakvank is a small monastery near Dilijan.

This monastery is located in the forest, and a small road full of potholes leads to it. Although the monastery is mentioned in many travel guides to Armenia, it is not a touristy place at all. The monastery is too small to come here specifically for it.

Jukhtakvank is so overgrown that it can hardly be seen among the trees.

The name “Jukhtakvank” is derived from the word “jukh”, which means “pair” in translation. The word “vank” means “monastery.” Thus, the name translates to “pair of monasteries.”

And indeed: next to the first church stands a second one, even smaller.

The temple is entered through old doors equipped with a simple iron gate.

Inside there is an altar. The walls reveal the age of the building: it’s from the year 1200.

A frightening discovery was made near the entrance to the temple. A niche was carved into the stone, reminiscent of an altar. There was blood in the niche. On closer inspection, I saw the remains of feathers. It seems that pagans still live in Dilijan. Someone sacrificed a chicken next to the ancient temple.

It was creepy to be in this place alone, deep in the forest. It was completely dark inside the second temple. There was also a simple altar in it. The walls were completely black from soot. On the left and right of the altar are niches in the wall that were used for prayer.

Next to Jukhtakvank, there is another monastery called Matosavank. It looks exactly the same and was built in the same years, so there is no point in visiting both monasteries.

Vanadzor. Lunch at Serian\’s

On the way from Dilijan to Vanadzor, there is a village called Fioletovo, where a religious community of Molokans lives. Their history deserves a separate story. In this part, I will only tell how Seryan decided to buy cabbage from the Molokans for our table.

“Andrey-jan, why do you want to visit the Molokans?”

“I accidentally heard about them just before the flight. I'm curious about how they live.”

“You know, they are very strange. They don’t communicate with anyone, they are all closed and suspicious. People here believe that they are witches. They wear these long beards, which split at the end, like the devil’s.”

“Seryan, have you met Molokans?”

“Yes, they sell cabbage by the roadside. I once bought from them. Tasty, damn it. You can’t find it anywhere else, they add something to it. You know, I want to tell you a story. A friend of mine came to them, wanted to buy a piece of meat. He was terribly afraid of them because he believed that they could put a spell on him. So he’s buying and asking, is the meat not enchanted? So the old Molokan man took and pulled out hairs from his beard. And stuck it into the meat. And he says: TRUH-TEEBEEDOH-TEEBEEDOH! That guy got scared, he yelled out: ‘Ah, fuck your mother!’, pulled out a knife and chased after the old man. He thought he had put a curse on him, they barely calmed him down.”

Seryan bursts out in a hoarse laughter, and I burst out laughing with him. Apparently, he is so overcome with laughter that his eyes darken and his hands weaken. He laughs so hard that for a moment he even releases the wheel, almost causing an accident.

At the turnoff to the village of Fioletovo, there really is a tent with sauerkraut. Seryan buys a jar from the Molokan and drives me to Vanadzor with a satisfied look on his face.

Vanadzor is the third largest city in Armenia with a population of 90,000 people. The city has a spacious square in the center and is surrounded by mountains.

In Soviet times, Vanadzor was an industrial center with a dozen factories, institutes, and enterprises. Now the city is slowly declining like any industrial center of the USSR period.

Seryan was born in Vanadzor and moved to Ejmiatsin. His family lives in Vanadzor: his elderly mother, wife, and two sons. Seryan’s house is located in the very center of Vanadzor, but it is old and dilapidated. It was built back in 1929.

The layout of Seryan’s apartment is quite typical for those years. The spacious living room is located in the center of the apartment. On one side, there are two bedrooms, on the other side — a kitchen with access to the balcony. There is also a narrow doorway leading to the bathroom, which is combined with a toilet.

An old carpet lay on the floor of the living room, which was so deeply embedded in the wooden floor that it merged with it. The walls were white and empty, only calendars and a mirror hung on one wall. There was also an old television set with a cathode ray tube screen and giant speakers taking up half of the panel.

There was unimpressive furniture standing on the sides of the living room. A wheelchair was tucked away in the corner. An old, gray-haired woman — Seryan’s 80-year-old mother — was lying on the sofa.

The atmosphere in the apartment turned out to be as modest as the lunch was rich. They greeted me like Chichikov in the governor’s house. They served mineral water, homemade apricot compote, a huge dolma the size of cabbage rolls wrapped in a cabbage leaf, a platter of red and green sweet peppers, mysteriously shaped crispy potato pies, stuffed eggplants, fresh parsley, a piece of salted butter, monstrously salty goat cheese with an incredible flavor, and the highlight of the meal — sauerkraut bought from the Molokans.

Seryan led me to the living room and introduced me, “Andrey-jan, please help yourself. This is my mother, who is disabled and has difficulty walking. And this is my son, who just finished school and was accepted into the institute.”

Mother sat up from the bed and began to say something in Armenian, quickly realizing that I only understood Russian.

“Andrey-jan, I’m eighty years old, I see poorly and hardly walk. How do you like it, is it tasty?”

“Thank you, it’s very tasty. Have you lived here for a long time?”

“A long time, a long time. Since we built the house. I used to travel to Moscow, from there I brought a lot of things. I can’t do it now.”

“Was it better in Armenia during the USSR than now?”

“It was different. You couldn’t buy anything, only procure. Everyone had acquaintances somewhere: a store director, a shop manager. They were always getting something. So everything was there. But medicine was better. Now, you know, half of the pension goes for pills, Andrey-jan.”

Seryan joined the conversation.

“Andrey-jan, you know, the Armenian diaspora is the largest in the world. I have acquaintances everywhere. One in America, another in Germany. I myself worked on a tractor in Spain in the nineties. I didn’t like living there, so I came back. Now I think it was in vain. My sister lives in Germany, another in the Netherlands. There’s an uncle in America. In Moscow, everyone I was friends with in childhood.”

“Why don't you leave?”

“Well, because I don’t have the money. I play the green card lottery, trying to win. Maybe I will leave. You see, Andrey-jan, there is no respect for human labor here. There, whether you're a taxi driver or a businessman — you’re respected. Here if you’re a taxi driver, you’re a nobody. And do you know how I slouch my back on this taxi? I wasn't like this before, I got fat from work. I don’t know how to lose weight. We eat a lot of bread. There’s no money for good food.”

By the end of the day, Seryan became noticeably gloomy. It was clear that he was tired from the trip. There was no trace left of his initial boisterous laughter and jokes, and his smile became forced.

⁂

On the way from Vanadzor to Yerevan, there is a tiny village called Tsilkar. The name of the village is all that remains of it. It is more like a settlement, a campsite of primitive people.

A herd of sheep is blocking the road.

In the rays of the setting sun, a strange cone-shaped dome with a star on top is visible.

“Serjan, what is this?”

“This is a Yezidi temple. They live here.”

“Yezidis? That’s a people from Kurdistan, how did they end up in Armenia?”

“Mostly refugees here, they were escaping from Saddam and ISIS. There’s another city in Armenia where they live. I can’t recall right now.”

I am searching for information about Yazidi settlements. It turns out that the world’s largest Yazidi temple is located in Armenia! I am adding the city of Aknalich to my travel plan.

The sun is starting to set, and Seryan speeds up to get to Yerevan before dark. Mountain roads in Armenia are very dangerous. There are no lights or dividing lines.

Completely exhausted, Serian glances at my latest model iPhone and sighs heavily.

“Andrey-jan, tell me, who do I look like?”

“You? You resemble Nassim Taleb.”

“And who is that?”

“He is a philosopher, Serjan-jan. A specialist in probability theory.”

“Is he good?”

“One of the smartest people, Serjan-jan.”

Serian opens YouTube on his old phone and types “Nassim Taleb” in the search bar. He watches and sees a striking resemblance. A smile appears on Serian’s face.

People love to resemble someone famous. It gives them a sense of belonging.