Tashkent

I first heard about Tashkent from the novel “Tashkent — the Bread City,” an unpleasant book about hunger after the revolution that somehow remained in the school curriculum until the 21st century.

Tashkent turned out to be a city of police, not bread. The last time I saw so many policemen, patrol officers, guards, and watchmen was in Riyadh when I tried to document an execution.

During my trip to Tashkent, there was some kind of summit taking place. It seemed like the President of Turkmenistan himself was visiting. Perhaps that’s why there were two policemen stationed every 100 meters along Nukus Street, directing all pedestrians into cafes, entrances, and shops during the passage of the presidential motorcade. Maybe that’s why, or perhaps they are here every day.

When I was taking photos at Independence Square, an Uzbek policeman approached me. “What’s wrong? — Delete it,” he said referring to the photo. “This one, what’s in it? — The presidential palace.”

Later, I restored the photo. You can see a piece of the presidential palace roof between the columns in the center of the frame.

I deleted the photo. I moved 100 meters away to the park and defiantly captured a close-up of the palace using a telephoto lens.

Another time, a security guard didn’t allow me into the central city park with my camera. I wasn’t even taking any photos; the camera was just hanging around my neck. He made me call his supervisor. The supervisor responded that it’s allowed to enter with a camera, but later, as the park is currently closed.

However, the mere fact that there is a metal detector at the entrance to the park (!), surrounded by a fence on both sides, is quite telling.

“Doctor, do you treat the fear of enclosed spaces?”

“We treat claustrophobia, of course.”

“Doctor, do you treat the fear of open spaces?”

“Yes, we also treat agoraphobia.”

“Do you treat if both fears are at the same time?”

“Well, no. We do not treat KGB employees.”

In general, it is better to capture Tashkent when there are no cops around, but the city itself is quite dull, with only a few noteworthy architectural structures.

Here, in the center, stands the beautiful Soviet hotel “Uzbekistan.”

A typical Soviet brutalist style, but with a national pattern.

The hotel was built in 1974. In terms of its shape, it resembles the Hotel Cosmos in Moscow’s VDNKh, which appeared five years later.

Right in front of the hotel is located the square of Emir Timur, better known as Tamerlane.

It turns out that the name Tamerlane is considered offensive. It originates from the nickname Timur-i-Leng, which translates from Persian as “Timur the Lame.” That’s why in Uzbekistan, he is simply referred to as Timur, with the title of Emir added.

A monument to Tamerlane is installed in the square.

The memorial plaque beneath the monument, written in four languages, states that “strength lies in justice.” Perhaps so, but what does it have to do with Tamerlane? As I was later told in Tajikistan, “Uzbeks have gone completely mad with their Tamerlane; he was a bloody bastard.”

Indeed, Tamerlane is considered one of the bloodiest leaders in human history. It is now difficult to determine the exact number of people he killed. Estimates converge around 17 million people.

Considering that during Tamerlane’s time, the world’s population was significantly smaller, it can be concluded that Timur was the most ruthless individual in human history. He exterminated approximately 5% of the Earth’s population.

It is not surprising that everyone in Uzbekistan unanimously supports Russia in the war with Ukraine. The cult of personality here surpasses even Putin’s by tenfold. Mausoleums are even being built for the former president Karimov.

In addition to the monument, there is also a museum of Tamerlane in the city. It has decent architecture, considering that it was built in 1996 as a modern construction. The mausoleum was constructed by the same President Karimov.

The composition of national pride is completed by the globe of Uzbekistan.

Sometimes Tashkent even slightly resembles Ashgabat, although it is still far from reaching the level of the extravagant “Turkmenistan” known as Gurbanguly.

There is barely enough to do in Tashkent for half a day. There are hardly any interesting places. The widely promoted Minor Mosque, built in 2014, looks like a misunderstanding, although it appears better than the mosque in Almaty.

Another mosque under construction, this time a large one.

There is a Japanese garden on the outskirts of the city that is either not yet open, already closed, or on lunch break. Not far from the garden stands a charming television tower. It was built during the Brezhnev era, just like the only decent hotel.

Arguably, the only interesting place in the whole of Tashkent is the Imam Hazrat Complex. Some buildings of the complex were constructed as early as the 16th century.

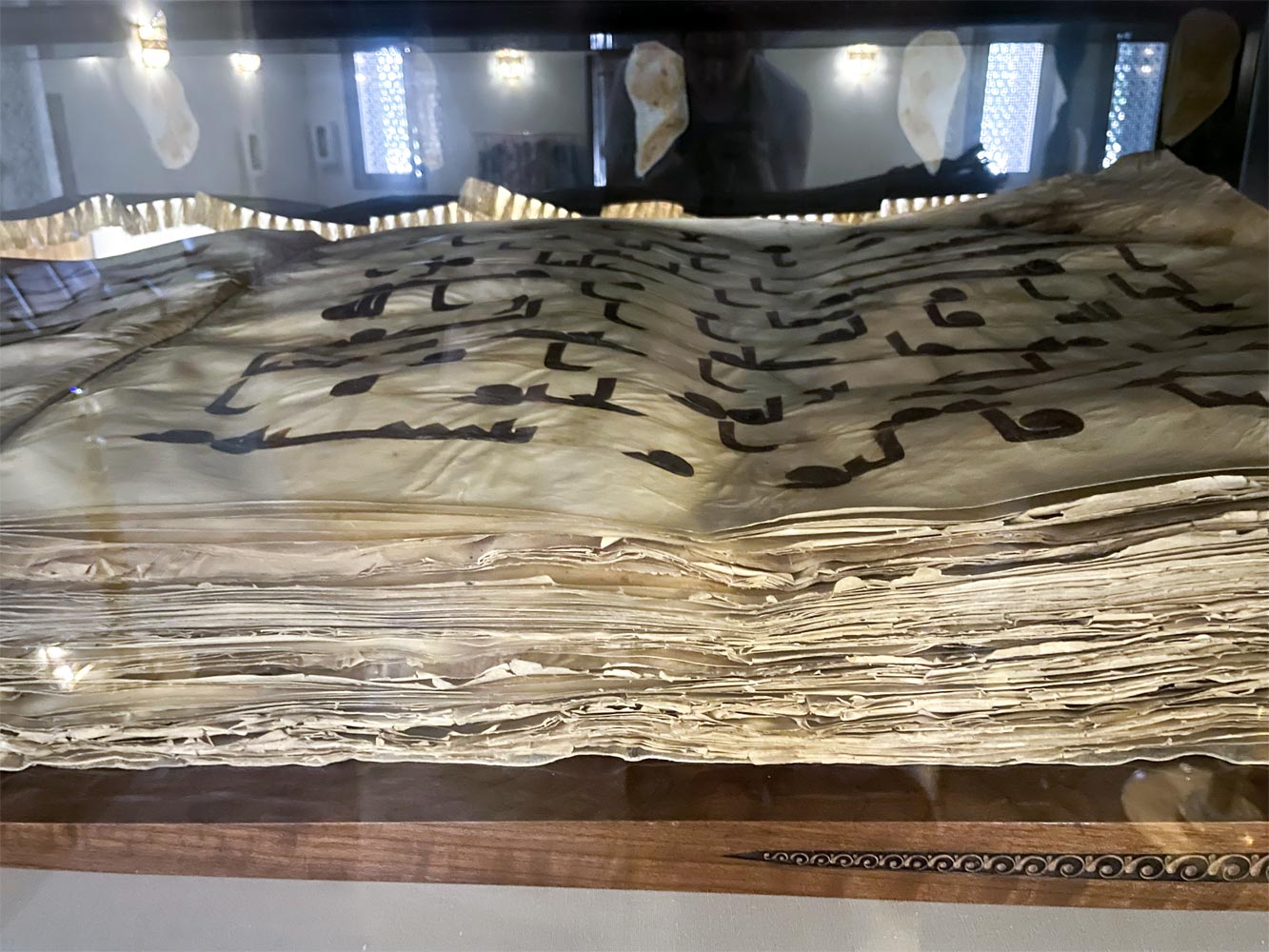

Here is an old madrasa (Muslim school) where a real treasure is kept. It is one of the six earliest manuscripts of the Quran that the thief Tamerlane smuggled out of Iraq.

The fact is that, in reality, the Quran, which Muslims claim was created by Allah Himself and has reached our time in an unaltered form, was actually written in six editions, five of which were distributed to all regions of the Arab caliphate.

However, the ruler of the caliphate at that time, Uthman, kept one copy of the Quran for himself. Later, it was transported to Iraq, where it was preserved until the invasion of Tamerlane.

This is an incredibly important object. Perhaps it is the oldest Quran in the world. It is strictly forbidden to photograph it, and there is a guard constantly watching from behind. Look at those pages.

Outside the center, Tashkent is quite poor. Occasionally, one can come across some decent architecture, but it is more of an exception.

Many neighborhoods are built with Soviet-era seven-story apartment buildings.

The houses are in acceptable condition.

Sometimes the entire street is cluttered with advertisements.

The city market is a misunderstanding.

In Tashkent, you can come across very dilapidated neighborhoods, but it is more of an exception too.

The further away from the center, the more one feels the presence of the East.

The more often you can encounter women wearing hijab.

And children who play with a cart.

Yes, people definitely don’t come to Uzbekistan for Tashkent.

People come to Uzbekistan for Samarkand!