Baku

It is cheapest to fly from Moscow to Iran via the capital of Azerbaijan, Baku. Either there or back, there is a long layover. Eight hours should be enough to explore the small capital of the former Soviet Union state.

Baku airport is beautiful, convenient, and clean. There are usually few people here, so you can sleep peacefully on the soft couches in a corner on the third floor at night.

The prices at Baku cafes are surprising: in the most luxurious restaurant at the airport, you can eat dolma to your heart’s content for 500 rubles. The waiters are not just smiling and friendly, but more than that: the greeter even jumped in place when he heard my Russian speech and shook my hand firmly.

In general, the last place I expected to see Europe was in Azerbaijan.

The only serious issue with the country is the obsession with the conflict with Armenia. After the collapse of the USSR, the two countries failed to divide the small region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The conflict in Karabakh became so intense that since the mid-90s, Azerbaijan has not maintained any relations with Armenia or Armenians.

While the discord between their governments can be understood, the contempt towards people cannot be justified in any way. The issue of nationality is so acute in Azerbaijan that the unpleasant Soviet term “nationality” is heard everywhere.

Perhaps, only this sets Azerbaijan apart from Europe. There is no such word in Western dictionaries! “Nationality” in English, “Nationalité” in French, “Nacionalidad” in Spanish — these words denote a person’s belonging to a country and state. Only in the Russian language does this word mean ethnic affiliation. In Russian, and in all the languages that remained on the ruins of the former Soviet Empire.

Upon exiting the Baku airport, a polite and smiling woman takes my passport, flips through it and asks:

“What is your nationality?”

“My… what?” Having forgotten this word, I thought I misheard.

“What is your nationality?” The passport officer repeated.

“Um. Russian,” I answered, dropping my pince-nez from my eye.

“Pure?” The passport officer shot me point-blank with a shotgun.

“Pure. Russian. Yes,” I was preparing to give a urine sample.

“Welcome to Azerbaijan.”

“Wel... I mean, thank you!”

After that conversation, it took me a long time to recover. It turned out that they ask about nationality not only at the passport control — as part of their duties — but also randomly in the city, out of curiosity.

Several times during my short visit, ordinary people in Baku asked me a simple question: “Are you Russian?” and responded with: “Oh, what a wonderful nationality!”

Indeed, nationality is quite significant. There are several video recordings showing what can happen to someone with a “negative” nationality in Baku. Depending on the time of day and the location where an individual identifies themselves as Armenian or speaks Armenian, they can expect different reactions from Azerbaijanis, ranging from strong misunderstanding to threats on their life. The reaction in Armenia, however, would be symmetrical.

The cultural shock from this conflict has stayed with me for a year already. Fortunately, it is the only major downside of Azerbaijan. Well, for a tourist at least.

⁂

The second wave of cultural shock hit me in the center of Baku when I saw English cabs instead of taxis.

At first, I thought the cabs were brought as a prank during the racing championship taking place in Baku at that time. It turned out that they have been here since 2011, and the state itself directly purchased thousands of them from Britain. The Baku cabs differ from London cabs in color: instead of black, they are purple.

Finally, the cultural tsunami hit me when I arrived at the waterfront. Here, I realized: Baku is an amazing, clean, modern, and cool city.

A long park is spread along the waterfront. The influence of Russia is only revealed by the Sobyanin’s tile.

But, let’s say, it’s a shortcoming. However, in certain areas, the center of Baku resembles Madrid or Lisbon.

The only things that give away that it’s not Europe are the protruding panel buildings and the awkward attempts of shopping centers to imitate classicism. However, you can find such things in the USA as well. In Las Vegas, for example.

Overall, it’s hard to believe that I ended up in Azerbaijan. In the center of Baku, the neoclassical architecture has an Asian touch, but if you don’t look closely, it could pass for Paris. The wavy pattern on the pavement is clearly inspired by Spain. The building of late 19th century obviously.

Baku is eclectic.

Here is a complete mixture of architectural styles. Many buildings in the center have remained since the time of the tsars. Somewhere among the row of clumsy neoclassical houses, there is a very pronounced Art Nouveau building—the opera and ballet theater.

But the real pleasure in Baku is its old city. Everyone knows that Azerbaijan was part of Iran before it was conquered by the Russian Empire in the early 19th century, right? So, the old city of Baku is a small preserved piece of Persia.

Here, you can even come across dome-shaped granaries, though they are purely decorative.

Old Baku is not as modern and clean as Yazd and Isfahan, but it also has its own labyrinths and narrow streets.

Somewhere, Baku resembles Jerusalem or some part of Turkey. The streets suddenly become wide, paved with granite and filled with white cars.

It seems that in a warm climate, any decay can pass for beauty.

A classic wooden balcony in Arabic style is attached to a stone house with ornamental moldings. It resembles Jeddah in Arabia, but in a modern way. An incredible combination of styles.

Baku has a European body but an Eastern soul. What is it? Jerusalem or Madrid?

House.

Doors.

Plaque on an old mosque. On the left, there is Quranic calligraphy.

Artifacts of time: a telephone booth, a sewage manhole from the Tsarist era, a pre-revolutionary sign that says “Bank”.

The architectural chaos of Baku does not end there. What is that peeking in the distance, beyond the Arabic ornamentation?

And this is the “Flame Towers” complex. Inside, there are apartments, hotels, and offices. It was built in 2012. I’m not sure what meaning was intended with the shape, but it resembles squawking pigeons.

Not only are the towers the tallest in Azerbaijan, but they are also situated on a hill. They may look fine from afar, but up close, you can see a thick layer of dust. The shape of the towers is somewhat flat, which collects all the dust.

Baku appears quite unremarkable from a height.

⁂

During the twilight years of the USSR, an old conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia rekindled over Nagorno-Karabakh. Once, during the years of the Revolution and the Civil War, the countries had already fought over the territory of Karabakh, and now the war began again.

Interestingly, the first war erupted during the collapse of the Russian Empire, while the second one occurred during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As long as both republics were part of the larger hyperstate, the conflict was mitigated, and it didn’t escalate into a full-blown war.

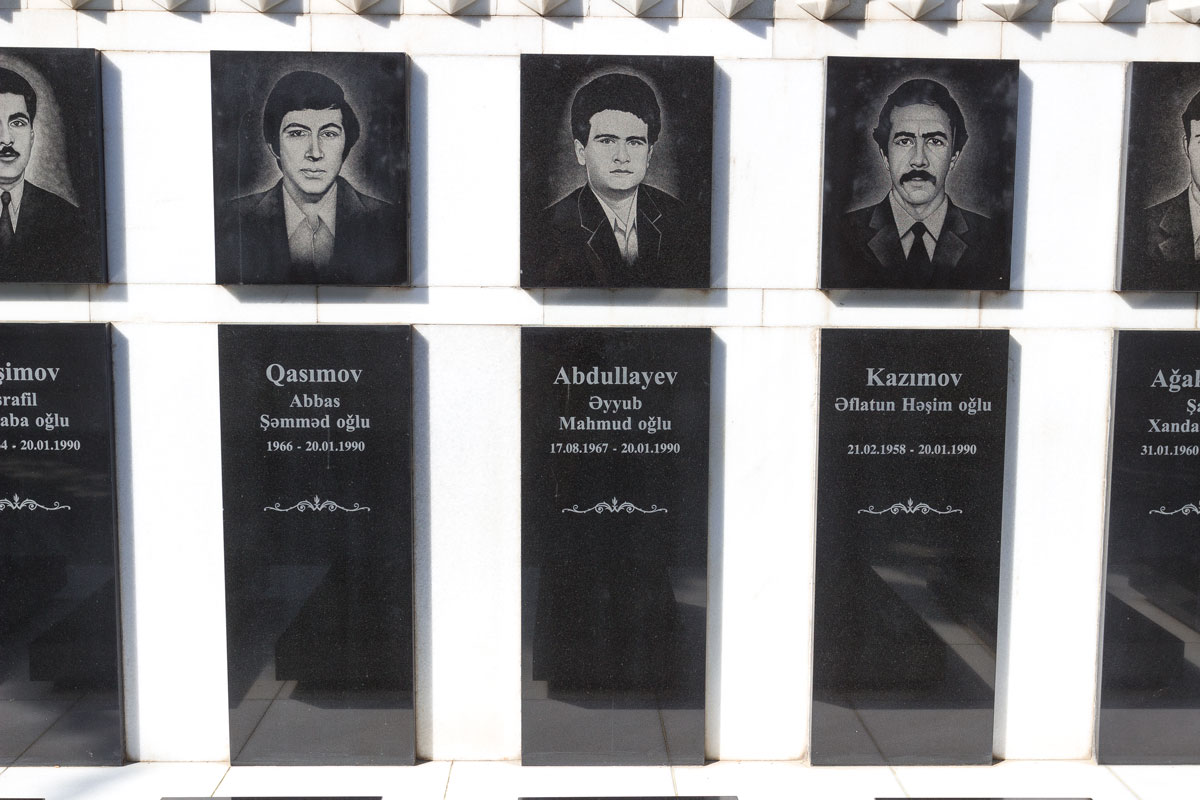

The conflict in Karabakh began in 1987 and escalated progressively, resulting in increasing casualties. By the early 1990s, the conflict had evolved into a powerful national movement in Azerbaijan. On the night of January 20, 1990, Soviet Army special forces were deployed to Baku and suppressed the opposition protest.

Azerbaijanis refer to these events as the “Black January.” During that time, as a result of the harshest suppression by Soviet military gunfire, around 130 civilians were killed, and 800 people were injured.

A dying empire, fueled by anger towards itself, willing to kill thousands of its own citizens just to cling on to power for another year — a pitiful and bloody spectacle that, perhaps, we may witness once again along the borders of modern-day Russia.

The victims of Black January were laid to rest in Baku at the Alley of Martyrs. It is the same place where the victims of the war in Karabakh in the 1990s are buried. It is also where Stalin leveled and cemented the old cemetery with those fallen in the Karabakh war as early as 1918.

Fortunately, the memory of Azerbaijanis is alive. “Shahid” in the name — no need to laugh — is an Arabic word meaning someone who died in war while defending their family, honor, and homeland. In total, on this Alley of Martyrs, which includes those who perished in the war and fell victim to Soviet terror, there are 15,000 people. Azerbaijan remembers them all.

This is how it was. And now in Baku, it is peaceful and good. Everyone, come here.