Balaklava

Balaklava is a small town with a population of 23,000 people located in Sevastopol. During the Crimean War of 1853-1856, a battle took place here between the Russian Empire and Great Britain.

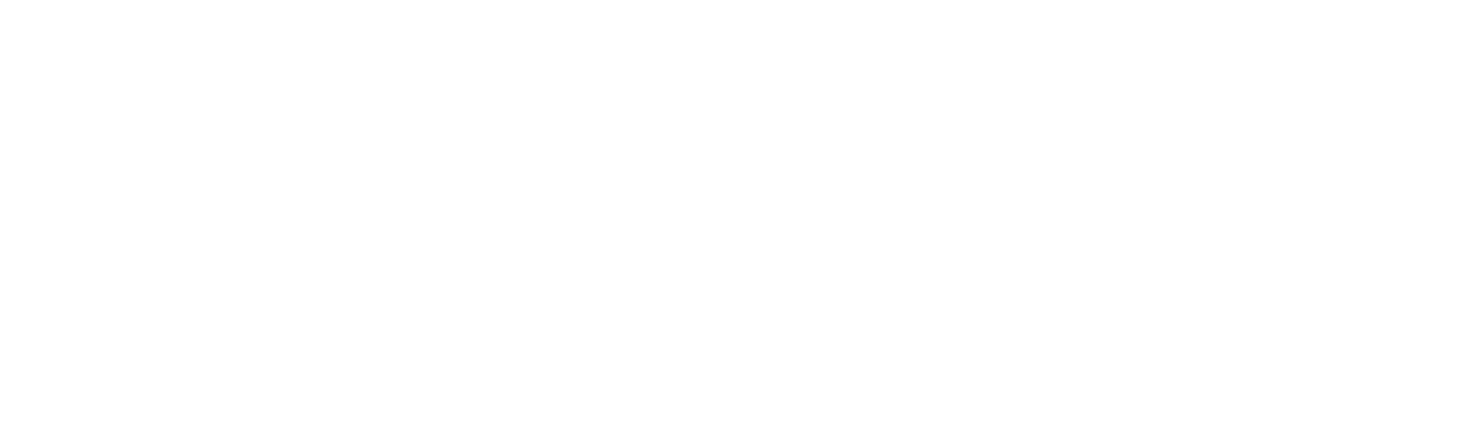

One of the battles, known as the “Charge of the Light Brigade,” went down in history as a shameful defeat for the British troops and gave rise to three fashionable clothing items.

The balaclava mask, which is now worn by various criminals during bank robberies or dispersing demonstrations, was named after the city of Balaklava. The mask itself was known for centuries before that and was worn by knights. But during the Battle of Balaklava, one of the varieties of this mask, which completely covered the face, began to be sewn to protect the British army from the cold.

The battle was commanded by James Brindell, better known as Lord Cardigan. In the same battle, he came up with the idea of taking an ordinary jacket, knitting it from warm wool, and attaching sleeves to it. Thus was born the famous sweater, now called a cardigan.

Another British commander-in-chief, Field Marshal James Henry Somerset, carried the title of Baron Raglan. In 1815, at the Battle of Waterloo, Raglan lost his right arm, and in 1854, during the Crimean War, he was promoted to general and became the commander-in-chief of all British forces. To conceal the absence of his arm, Raglan came up with a special way of attaching the sleeve to the garment. He used a longitudinal seam that extended to the neck instead of a cross seam. This made the hanging sleeve without an arm less noticeable, and the cut itself provided good protection against water because the seam did not get wet in the rain. The name of this type of sleeve — raglan — is less well-known but also originated from Balaklava.

It’s a pity that Russia won in such an epic war, while Britain wears fashionable clothing.

Balaklava is a completely unremarkable town resembling an industrial zone. This is one of those cases when the history is much more interesting than the place itself.

On the outskirts, the town looks abandoned. Old shabby houses, asphalt rivers, and no street lights at night.

Throughout the town, meaningless monuments are scattered, which no longer evoke any feelings.

Shabby signs from the 90s hang along the roads.

In the center of Balaklava, there are ruins of some interesting buildings in an incredibly monstrous condition.

The city waterfront, also known as the pier, is the only historic street.

Beyond this street, like this:

In general, the entire Balaklava is a bay. Boats are parked here like minibusses at a bus station. People come, get into a boat, and go somewhere.

Anyway, what am I talking about? Balaklava is a strictly military, closed city of the USSR. Here, everything is about war and only about war. The bay itself has such a shape that there are never any storms in Balaklava. This can be clearly seen from the old lighthouse on the edge of the town. The bay twists and turns in such a way that waves simply do not reach the pier.

The whole town is essentially a large military base. There are kilometers of tunnels dug into the mountain where submarines used to be made. Massive fortifications protrude outward. It is impossible to break through such defense.

The entire history of Balaklava is connected with war. On the surrounding hills around the town are the remains of the Chembalo fortress, built by the Genoese in the 14th century. Later, Crimea was captured by Turkey, and a Turkish garrison was stationed in the fortress.

Now Balaklava is dominated by a certain surrealism. An ancient fortress, barbed wire, a disgusting Turkish center, walls covered in graffiti, and houses that are in much worse condition than the ancient fortress.

The only interesting museum in town — the former submarine base — turned out to be closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Oh well.

What’s good about Balaklava? There are a thousand boats, every tenth of which is a restaurant. Twenty types of fish priced from 100 rubles. I’ll order something tasty:

“Can I have flounder?”

“There’s no flounder, it’s not the season.”

“Then halibut.”

“No halibut either. We only have this and this.”

“Why are there only two types of fish on the menu in the whole city?”

“Well, it’s not the season. We don’t serve frozen fish, only from the fresh catch. And there’s no catch now.”

At that moment, all of Balaklava’s sins were forgiven, and I ordered some herring. The sun was setting towards the west. In the distance, vineyards were growing, from which Balaklava brut was produced.