Crimea and Ukraine

It is amazing how much material and debate has been dedicated to the “problem of Crimea’s belonging” when in reality there is no problem.

Most people argue about the legal nuances of Crimea’s annexation to Russia, delve into old border protection treaties, refer to legal dictionaries on the terms “secession” and “annexation,” compare Crimea to Kosovo, Karabakh, and Alaska. Nobody understands the main thing. An agreement is considered valid not because it is drawn up according to some rules or laws, but because it is universally recognized. At the same time, “universal” does not mean by everyone.

Suppose you decided to sell yourself into slavery and entered into a contract with your master obligating you to work for food for the rest of your life. The legal system does not recognize this contract, even if it is written in exact accordance with the law. If you decide to leave your master and he takes you to court, the court will simply declare the contract void and set you free.

Meanwhile, there are probably countries like Somalia where this contract may be recognized. So what? The opinion of a Somali court is of little concern to the rest of the world.

The example with slavery is the most striking one, but not the only one. There are dozens of cases where a contract is considered invalid, even if it was concluded by mutual consent and in accordance with the law:

• the purpose of the deal contradicts morality,

• the deal is made for show,

• the deal is made under a misconception,

• the contract is made with the intent to cover up another deal,

• the contract is concluded without the consent of a third party,

• the contract is made by a person who has not reached the age of 14.

I prefer the last point: Crimea was underage when it entered into a contract with Russia.

Friends, a nation’s path to self-determination is a years-long struggle, with protests, demonstrations, cultural and religious divisions. This path cannot be traveled in 2 weeks, as happened with Crimea — you can’t even get married that fast, let alone change countries. Until 2014, there was not a single mass protest in Crimea in favor of joining Russia. I don’t remember any struggle by the Crimean people for any rights. There was only a sluggish nostalgia. Then Ukraine plunged into political crisis, which Russia deftly took advantage of, playing on the momentary desire of Crimeans to “get away somewhere” far from the chaos.

I am confident that Crimea honestly voted “for” joining Russia. The problem is that the treaty on accession to Russia has been recognized only by 7 countries like Afghanistan and Syria.

For some reason, this argument is considered secondary, but it is the only objective criterion of legitimacy. An agreement must be universally recognized to avoid being legally void, and this is the essence of an agreement as a phenomenon.

The world voted against it: Crimea is Ukraine. As for the author, I am a localist and would like to see not only a Crimean Crimea, but also a Muscovian Moscow and a New Yorkian New York.

Simferopol

Simferopol is the capital of Crimea. They say it’s a completely uninteresting city that serves as a transit point on the way to Yalta. That’s why I only budgeted one day for Simferopol. It was the first hint of adventure: when there’s not much time — they’re bound to happen.

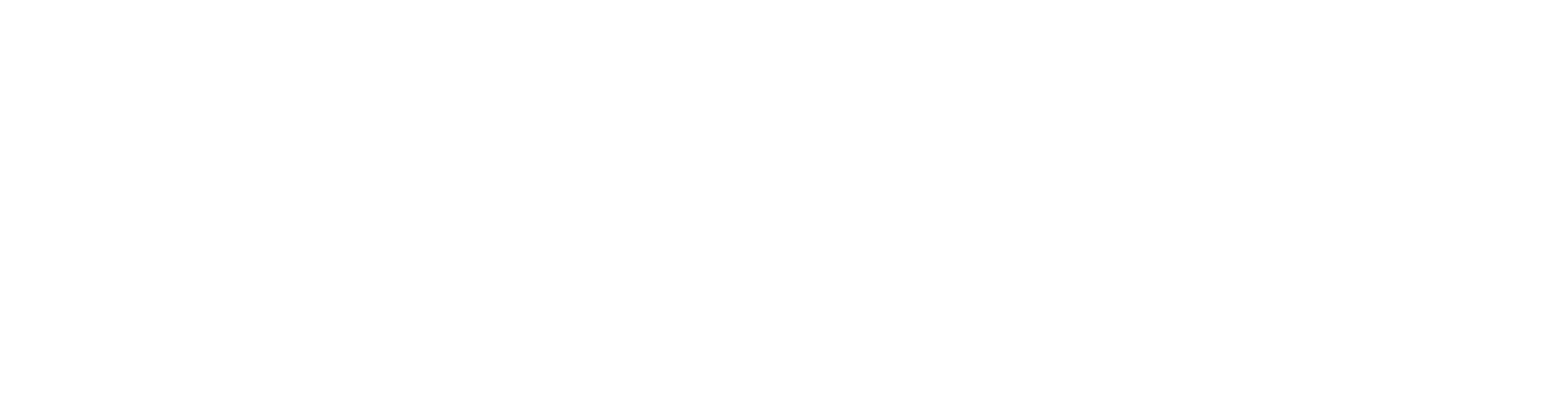

At first, it turned out that there were big problems with water in Crimea. In the news, it all seemed like exaggerated propaganda: well, what’s the big deal if some remote village doesn’t have water. But the biggest water problems turned out to be in the capital, Simferopol. The hotel had a schedule of hot water supply: a few hours in the morning and evening. Cold water, as the news reported, often came out murky, brown, with pieces of rust, and unsuitable even for brushing teeth.

Before Crimea came under Russian control, the peninsula was supplied with water from Ukraine, from the Dnipro River, through the North Crimean Canal. The canal was closed due to the military conflict between us. I wonder what the military strategists were thinking?

“Comrade Commander-in-Chief, I urgently contacted ecologists. They say that Crimea gets its water supply from Ukraine. We could cause an ecological disaster.”

“It's too late, it's already ours.”

Now various projects are being devised to supply water to Crimea. They suggest drilling deep wells, building water pipelines, and desalinating seawater. So far, the reserves in reservoirs are declining, and the problem is being solved with the help of blue barrels that are located throughout the city. Just like in Palestine where rainwater is collected in black barrels on the roofs of houses.

It’s not surprising that the residents of Simferopol turned out to be rude and uncultured. Try living without water, and on top of that, tourists are drinking and washing. The attitude towards guests here is terrible. In a budget hotel, there was an air conditioner, but the remote control for it cost 150 rubles per day. The beds were advertised as double, but turned out to be single. The hotel owner gave a stern look to the bourgeois and said: there are two beds, what else do you need?

The hotel was located in a pleasant old building, and right at the exit stood a rural house with a tiled roof, whose fence was completely covered with blue ivy. Opposite was a red Peugeot car.

So the first shot from Simferopol turned out like this, and I almost thought that the whole city would be a parade of colors, flowers, and beautiful cracks on the walls of houses. However, the only thing that haunted me until the end of the journey was puddles and broken asphalt. And they don’t drive red Peugeots in Simferopol. But there are many old Zhigulis, Moskvichs, and Volgas in the city.

In short, Simferopol is in a monstrous state. Everything without exception is broken in the city, as if the war ended yesterday.

The city is in such ruins that even benches in the courtyards are made of boards and scrap metal. The blue and white border seems to have been there since Soviet times.

Sometimes it seems like I ended up in an abandoned town in the far north, like Vorkuta. Residential buildings in the center of Simferopol look abandoned. There is nothing in the courtyards, only patches of asphalt with weeds growing through them. It looks similar to Pripyat, only the houses are better preserved and there are no cars.

The playgrounds look like reservations for inmates to walk around after the Armageddon in Los Angeles.

The houses are covered with homemade balconies, which are made of boards, metal sheets, plywood, and closet doors. There is nothing in front of the houses. An empty soccer field scorched by the sun, overgrown trees, rusty gates from the 70s.

Pipes hang over people’s heads in the courtyards. This is done either in northern cities to reduce the risk of accidents or temporarily while laying pipelines. In Simferopol, this is a normal way of life.

Throughout the city, there are abandoned buildings: cinemas, cultural centers, former research institutes, and state archives — all of it has long been abandoned, decaying and falling apart.

The train station is an example of an Eastern bazaar, filled with taxi drivers, minibus drivers, scammers, cargo women, and other riffraff who are trying to earn a living somehow.

This is how a tourist who got off the train sees Simferopol. And the first impression is not deceiving at all.

Although the train station itself is not bad. Guidebooks write that it was built from Inkerman stone in the post-war Soviet style of triumph. It’s not entirely clear who benefits from this. You can’t spread stone on bread, and you can’t put triumph in your pocket.

Just move 300 meters away from the train station, and at night you can get your head cracked with this Inkerman stone.

Simferopol is similar to some province like Ryazan. The title of the capital of Crimea is a misunderstanding. It’s just that the only airport for the entire peninsula is located here.

As in any provincial city, there is only one decent street in Simferopol — Pushkin street and the adjacent alleys. This is the local Arbat. There are many cafes and youth gatherings here. It’s okay for rural areas.

It is clear that not only Russia is to blame for this ruin, and the cities of the republic have been decaying for two decades before annexation.

It is also clear that sanctions are hindering normal life in Crimea.

It is unclear why Russia is again painting beautiful facades. We are restoring churches, temples, administration buildings — only symbols instead of something really important: a comfortable life in the city.

Posters are hanging here and there. Here, they restored the cathedral by a personal decree of President Putin. Well done, by personal decree of the president.

And who will restore the entrances and roads, your majesty?

King of the old city.

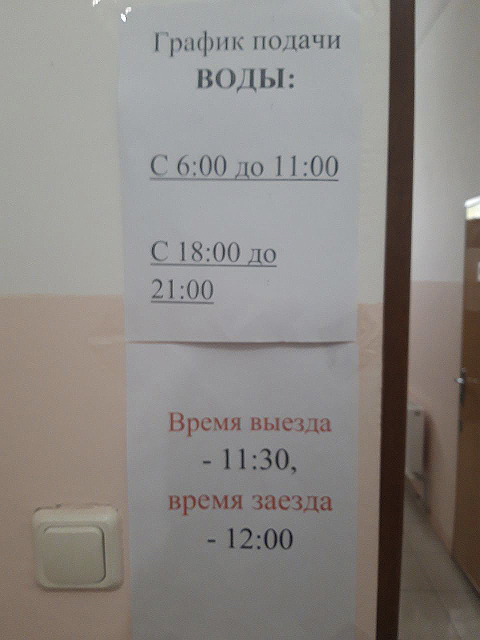

In Simferopol, there is a district marked on maps as the Old Town. It is located on the other side of the Salgir River, which runs through the entire city and is squeezed into a neat quadrangle between the Salgir, the ruins of Scythian Neapolis, and Krasnoarmeyskaya, Kavkazskaya, and Karaimskaya streets.

Karaimskaya: what an interesting name. The Karaites are a small ethnic group of only two thousand people around the world who have a history that dates back to the Karaite religion.

Karaism is a branch of Judaism that opposes all other forms of Judaism. The majority of Jews practice Rabbinic Judaism, which takes its name from the Talmud — a large collection of rules and principles of Jewish religion, serving as an interpretive guide to the Hebrew Bible.

Karaites do not recognize the Talmud and believe that each believer can interpret the Hebrew Bible as they see fit, rather than relying on the Talmud’s interpretation. The name “Karaim” comes from the ancient Hebrew word “kara.” The Arabic word for “Quran” is derived from the same root. Both words mean “reading”.

There is a small community of this disappearing ethnic group in cities such as Yevpatoria, Feodosia, Bakhchisaray, and Simferopol in Crimea. About three hundred Karaites live in the Old City of Simferopol, where the old Karaite synagogue, the Simferopol Kenassa, is located at the entrance.

The Kenassa was built in 1896 in a combination of Gothic and Moorish styles.

This is a unique building. There are only ten Kenassas in the world, and only three of them are operational. The Kenassa in Simferopol stood abandoned for a long time until it was handed over to the Karaite community. Occasionally, religious services are now held there.

The Kenassa marks the beginning of the Old City of Simferopol.

Simferopol was founded in 1784 by Catherine the Second after the annexation of Crimea to the Russian Empire. However, this does not mean that there was nothing before Simferopol in its current location. The Crimean Peninsula, also known as Taurida, is one of the oldest regions in the world. The ancient Tauri people lived in Crimea as early as the 6th century BC. Throughout its history, Crimea has changed hands many times. At different times, it was ruled by Tauri, Cimmerians, Greeks, Scythians, Pontic people, Romans, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Armenians, Alans, Tatar-Mongols, Genoese, Ottomans, Ukrainians, and Russians. Therefore, there were already settlements at the site of Simferopol before our era, and to say that the city has existed since 1784 greatly simplifies its history.

Before its founding, Simferopol was called Aqmescit. The prefix “aq” means “white” in Tatar, Azerbaijani, and Kazakh and is sometimes found in the names of cities in Kazakhstan, such as Aktobe, Aktau, and Aksai. “Mescit” is a distorted Arabic word “masjid”, which means “mosque”. Thus, the old name for Simferopol was “White Mosque”.

The familiar Crimea, whether it is Ukrainian or Russian, ends at the entrance to the old city of Simferopol. The real Crimea begins, which belongs to itself. From the alley, there is a breeze of the Middle East, and the streets narrow and twist into a tangle. But it’s not that easy to get into Akmescit. You need the permission of the King.

“Excuse me, good day. So, here’s the thing. I’m a local poet, and I forbid myself to be photographed.”

The King appeared out of nowhere, as if from a tobacco smoke. He looked like the devil himself: he wore black jeans and a short-sleeved black shirt, walked on worn black shoes along the black asphalt; his hair was also black. He resembled both Victor Tsoi and Keanu Reeves at once. The attire of a rock musician suited his tanned figure and sharp face well. Thin hair was combed back and reached his shoulders. They were unwashed and unkempt, but for some reason looked very creative. The devil had not shaved for three days. Thin mustache and goatee outlined his face. In short, he looked like a conquistador, the devil, the demon, or the King.

“I demand you delete the photos you just took,” the King ordered me with a dry, confident voice, “I forbid you to photograph me.”

“Buddy, I was photographing the street. You are not in the photo, I’m not interested in people.”

“I could have been caught in the frame and I demand you delete the photo, even if it’s just my leg in it.”

“What sense do you see in this? What does it matter if a leg got in the frame?”

“I’m a local poet. Everyone here knows me, and I don't want to appear in any form on social media. Delete the photo.”

Most of all in the world, I hate it when I’m prohibited from taking pictures on the street, and I’m usually able to withstand even an army of Arabs at a bazaar. But here, in Simferopol, I finally encountered a fundamentally reasoned position. A local poet! Well, how about that! “Can I hear your poems?” — I thought, but said something else:

“No problem, I’m deleting it. So, I can reshoot the street without you in it?”

“Yes, without me, take as many as you want.”

“I pretended to delete the photo. Slowly, trying to show superiority, I chose a better angle. Squatted down. Moved the lens around. Took several photos of the street from which the devil emerged.”

“So what kind of poet are you? What’s your name?”

“I’m a nameless poet. And I want to remain unknown.”

“As you say. Well, I’m off. Have a good day.”

“No sooner had I taken a few steps than the devil called out: ”

“Where are you planning to go?”

“To the Old Town.”

“You’ll get mugged there with such a camera, buddy,” the King cut me off, pointing at my DSLR hanging around my neck, “I wouldn’t advise you to go there. Turn around before you get into trouble.”

“Mugged? Is it dangerous there?”

“Do you even know where you’re going? This is the Old Town, Akmechet. Everyone here knows each other. I’ll call my people now, they’ll find you and chase you away. Are you looking for an adventure, why are you going there?”

“I’m going precisely because it’s the Old Town. I heard that there are old tram tracks here, preserved from tsarist times. Wanted to have a look. It’s culture, history.”

“History, huh...” The King spat disdainfully and nodded to someone in the direction, “Well, Yura, the guy seems alright, shall we give him a tour?”

“I looked to my left and saw an overweight Yura coming towards me from the alley, slapping his flip-flops on the pavement. He was a man of about forty-five with white, grey-tinged hair twisted into a rocker braid at the back, wearing knee-length cut-off jeans and a white T-shirt with a wide V-neck collar. A beige mail bag hung over Yura’s shoulder, and he carried a pack of cigarettes in his hand. His hair had yet to turn grey, remaining black, and his eyebrows were dense. He had the same goatee as Espagnolka growing on his chin, making me wonder for a moment if Yura was the King from the future.”

“We'll give him a tour,” Yura turned out to be a man of few words, “It’ll cost a beer.”

“Ruslan!”, the King stretched out his hand to me, “For 380 rubles, I’ll show you everything you want!”

Without waiting for an answer, Ruslan turned his back to the Old Town and led me away. Yura, still unsteady from drinking, followed behind, and I prepared myself for what I had already experienced a hundred times in India, Morocco, and the Middle East — a crazy tour that would end in a farce.

“I’m a correspondent for the local newspaper ‘Komsomolskaya Pravda’. A correspondent. A poet by calling, I write poems. They are published in small editions by the local office. Yes, you can find them in the bookstore, but I won’t tell you my name. I don’t need ostentatious fame. Otherwise, I work in construction. I graduated from Rostov Military School. Buddy, you’re lucky you met me. If you’d gone to the Old Town now — you would have gotten your face beaten.”

“Are you serious, is it that dangerous there?”

“Yes. It’s a ghetto, slums. Everyone there is a local and they really don’t like strangers.”

“I’ve been to the slums of India and Morocco, everywhere I was met with friendliness. And here, everyone is one of us. How come Russian is an enemy to Russian?”

“This is not India or Morocco, mate. This is Akmechet, Simferopol. If a foreigner, who doesn’t speak Russian, stumbles in here, no one will touch him. But people like you won’t be welcomed. You can tell right away that you’re not a local. Where are you from?”

“From Moscow.”

“Oh, even more so. You Muscovites are rude and illiterate.”

“The King walked as extravagantly as he spoke. His speech was disjointed, jumping from one topic to another as easily as he jumped over puddles. He inserted interjections, whistles, clicks, made grimaces, and suddenly changed his intonation during the conversation. Sometimes he wrapped up his thoughts so skillfully that it seemed as though he suffered from schizophasia or a mild mental disorder.”

“The passing cars elicited snorts, grunts, and bristling from the King. He yelled at those driving through on green lights. To those who were slow leaving the Old Town, he made gestures with his hands, forcing them to quickly move on without delay. He sang ”Stewardess Named Zhanna“ to all the passing girls without exception, throwing elegant glances and making farewell gestures with his hand, as if inviting the lady to a ball. In short, he behaved not like a king or even a devil but more like a scruffy cat. Nevertheless, he definitely felt like a king.”

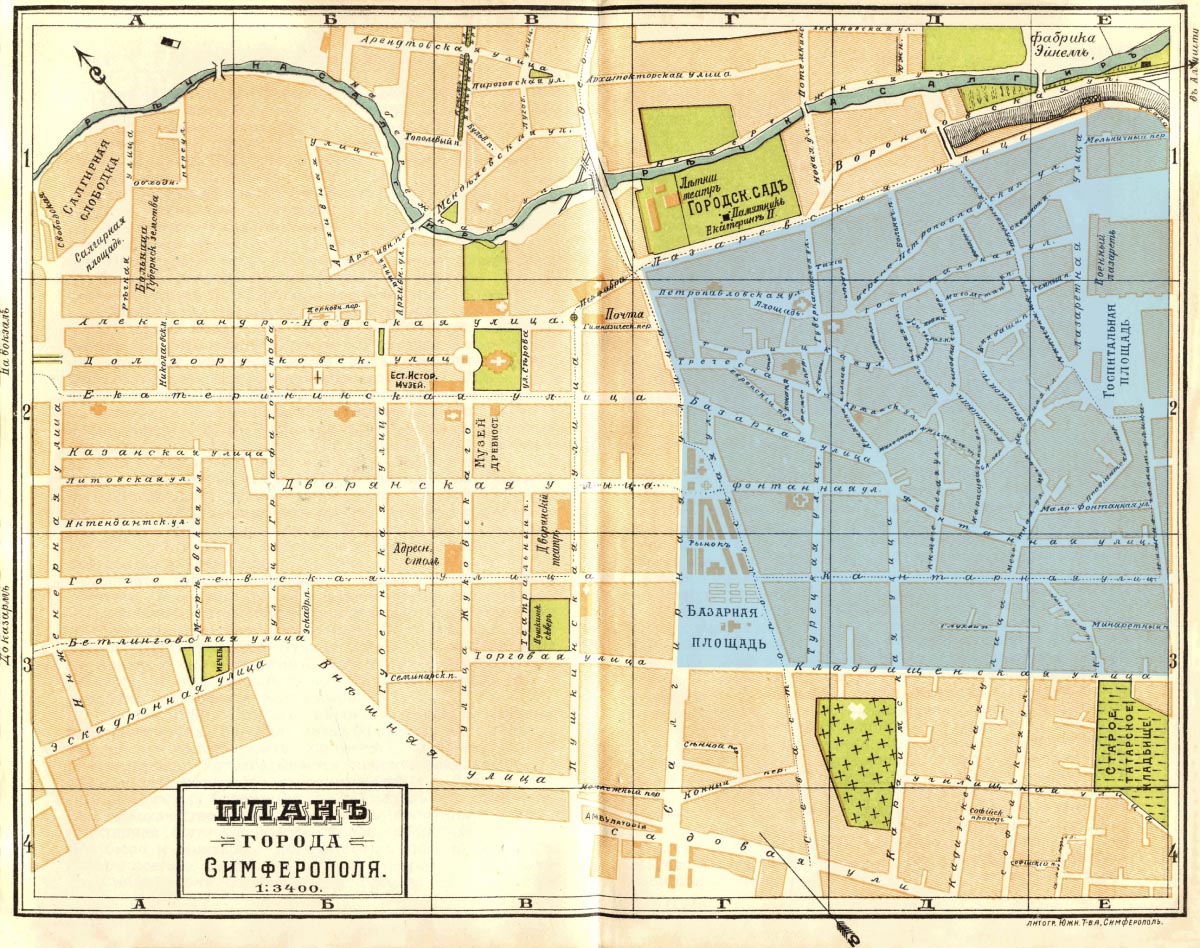

“Dear tourists, here is our first exhibit: a transformer station knot. Were you looking for the tram? Well, this is it. All that remains. Previously, tram tracks ran throughout the entire city, built back in 1914. Do you know who built them? Belgian engineer Bernard Borman. Designs were sent from all over the world, from Paris to New York. The tram network operated until 1970, then everything was dismantled and closed because there were no parts to repair it. The tram tracks remained until 2008, but now they are gone.”

“I looked up. In front of the temple stood a strange metal tower with thick wires passing through it in a bundle. The tower resembled a power transmission line and a watchtower in a prison.”

“This was a node of an old transformer station, the network of which powered the Simferopol tram and street lighting. The towers were built in 1912, and there are still several of them left in Simferopol. A real artifact of the Tsarist era! You can find the tower on old photographs of the city.”

“Let’s move on,” said the King, leading us away from the Old Town and continuing to show off his tricks. The traffic light was red at the crossing. The King snapped his fingers — and it turned green. “If he does it again, I’ll kill him,” he remarked about some guy who passed by. “And...,” the King took a deep breath, “I’ll throw someone in the river if I don’t smoke immediately.”

“No, he really did have a mental disorder. When we entered the ancient Trinity Monastery, he crossed himself. On the way out, he shouted ”Salam alaikum!“ to the workers. And just a minute later, upon seeing a sign that read ”Bolshevik Street,“ he began ranting about how much he hated Stalin and the Bolsheviks.”

“But you work at Komsomolskaya Pravda, right?”

“I do, so what? That’s different. The Bolsheviks are scum. They destroyed our country. Lenin was a genius, Stalin was a scumbag like the world has never seen. Although, they both were scum. I work because I have to. There are no decent newspapers here. I’m a monarchist myself, for the Tsar and for Russia to become an Empire again.”

“So you live in the Old Town?”

“Yes.”

“Since birth?”

“Since birth. We’ve lived here for three generations. I’ve lived in many places. Six years in Warsaw, two years in Leipzig, two years in Moscow. And I also lived in Japan.”

“So, you know Japanese? Anata wa nihonjin desu ka?”

“We call this place Vilnius because the houses and streets here are similar to the old town of Vilnius,” the King demonstratively ignored my question in Japanese.

“Realizing that I couldn’t decipher the King’s hints, I decided to switch to open action.”

“What about Ukraine? Are there any supporters of Ukraine in the Old Town?”

“A hell of a lot. In 2014, all of Crimea supported Russia. Now, the euphoria has passed. Fifty-fifty. Half of the town is for Ukraine, half for Russia. I myself support Russia. When all this started, I was in the front ranks. We stopped the ‘friendship train’ near Jankoy, which was coming from Lviv with weapons for Ukrainian fighters. Have you seen the film ‘Return to the Homeland’? You should watch it. I’m in it. That’s not the point though, we are fine with everyone. 87 ethnicities live in Simferopol. It’s a melting pot, we all live in harmony.”

“So people here have a good attitude towards Ukrainians?”

“Of course. It’s just that Ukrainians don’t understand that. When I was in school, all teachers were required to teach in Ukrainian. Why the hell do I need it? My teacher whispered in my ear: ‘Can I speak to you in Russian?’. Well, I understand the language, but it’s a lack of freedom!”

“What do the residents of the Old Town do, where do they work?”

“Mostly in construction. There is no decent work and there won’t be.”

“Do you think the district might be developed?”

“Never! We would fight tooth and nail before we gave it away!”

From questions about Ukraine, the King switched to top-notch three-story profanity. His religiosity and intelligence disappeared somewhere. He even cursed at the entrance to the temples, which he dragged me around for the next half hour. Then the King went all out and seemed to start composing a history of the city on the fly. But it was only an illusion.

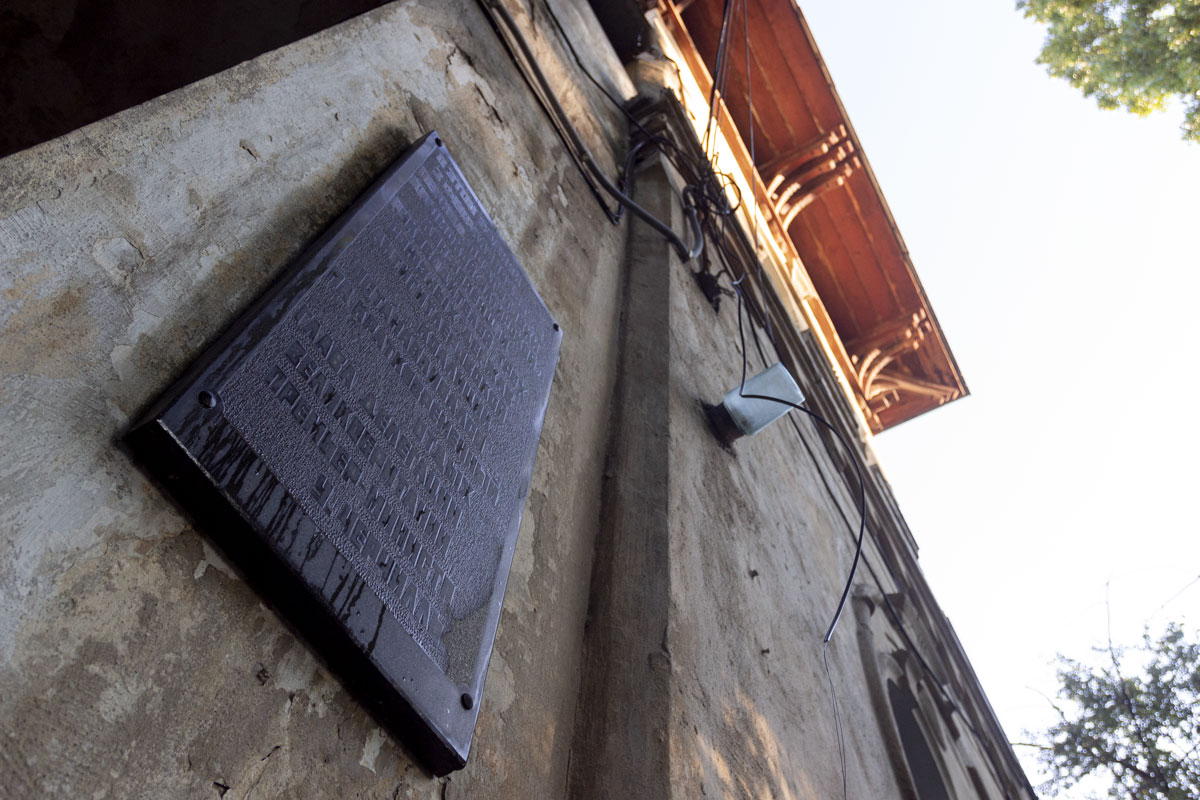

“This is the house where Griboedov lived. The former Athens Hotel. Here on this very balcony, he sat,” said the guide. I looked at the crumbling balcony with rusty railings and couldn’t believe that Griboedov could have lived here. But the plaque on the house really spoke of it. But even more incredible was what was inside the house. The King opened a plastic door and led me to the second floor. There was a clothing store selling junk for 200 rubles. Right inside a monument of architecture and history. “See how far Ukraine has come,” lamented the King.

After that, the King showed me the temple where Empress Catherine II prayed, the house where the head of the Hungarian Republic Bela Kun lived, the mansion where Winston Churchill stayed, the old building of the Imperial Stock Exchange, a Stalin-era cinema, and a fish store from the Brezhnev era in Brutalist style. The exhibits of Simferopol drove me crazy because, except for the temple, they looked like abandoned buildings, shopping centers, and travel agencies. And every time I started to doubt the truthfulness of the King’s stories, there was a sign, a pointer, or another detail that confirmed his words.

“And from this balcony, Nicholas II delivered a speech,” said the guide.

“Well, that’s enough! I don’t believe this. The balcony is newly built.”

“Come on, I’ll show you the plaque. Here, read it yourself. Why would I lie?”

“Damn this Simferopol! You’re right!”

“I’ve only shown five percent. Simferopol is the best city in the world! Yalta, Sevastopol — all that is nonsense. Moscow people come here with such airs, as if they are from the capital. We are the capital! Simferopol is the capital of Russia! And do you know what my name is? Rostislav Bakirov-Pavlin-Romanov.”

“A triple surname. You’re saying you’re related to the Romanov family?”

“I do,” the King nodded smoothly at me, with a mysterious smile.

Bakirov-Pavlin-Romanov was clearly getting carried away and at some point began to make up blatant lies. But we couldn’t catch him in the act. The King knew the city’s history surprisingly well, and in general, we had to believe him despite some exaggerations.

The tour was worth the money. They always are, even if the guide talks complete nonsense, you can still make a story out of it. The only thing I didn’t like was that he took us further and further away from the Old Town. We started to walk through the Soviet districts of the city, and instead of showing me the royal tram, he pointed out old store signs.

The King complained about the constant drizzling rain, but still continued to run around all of Simferopol. His lackey Yuri slowly dragged himself behind us, suffering from a hangover. The drizzle gradually intensified and turned into a real downpour, which drove us under the roof of some entrance. Yuri, who had been silent until then, suddenly joined the conversation, exhaling alcohol fumes and in a hoarse voice uttered the only phrase of the day: “Now it’s gonna fucking flood here. The city is on a slope. All the water flows towards the station, streets go...like little Christmas trees.”

Simferopol was flooded. The rain didn’t last long, but in ten minutes the city was underwater. Yuri and the King silently took off their shoes and walked barefoot through the puddle.

I insisted on going to the Old Town, which was taken away from me right in front of my nose:

The old city

“There’s nothing to do there, they’ll kill you. Come another time, I’ll show you.”

“Damn it, what’s going on over there, a mafia clan war?”

“Do you see, I’m missing four teeth?” — The King smiled, showing his knocked-out teeth, — “They found me, but the teeth are gone.”

“I see. Why did they knock them out?”

“A cop did it. You see, I like to sit by my house and play the guitar. Songs by Tsoy, Agatha Christie. I play and yell across the street. The cops don’t like it. One came up, snatched my beer bottle and drank it. I punched him. They caught me, took me to the station, knocked out my teeth, gave me two years probation. I’m still serving the sentence, so I’m keeping quiet.”

“That’s intense. I started to think there’s a drug mafia in the Old City.”

“There’s a fuckload of drugs here,” — The King again switched to foul language, — “If I catch a drug dealer, I’ll beat him to death, fuck. Once I came across one, he was digging something in the yard with a knife. Fuck, I say, you fucking idiot, in broad daylight on my street, bitch, you’re digging! We beat him up and handed him over to the cops. Drug addicts are like animals, they kill themselves with poison and poison others. Salt, amphetamine and what’s its name... mephedrone. All of Crimea is sitting on this shit, and the Old City is drowning in drugs. That’s why they’ll smash your head with a brick there. Don’t go. Neither day nor night. Neither on weekdays nor on weekends. Never.”

I parted ways with the King and started to think about how I could finally get to the Old Town and leave it alive and with my camera intact.

I didn’t believe the King’s stories about the danger of Akmechet, so I started asking everyone about the Old Town. The hotel owner said that “the area is very unstable, drug-infested, and criminal, and it’s better not to go there.” All the taxi drivers assured me that it was better not to walk through the Old Town during the day or at night. It even got to regular passers-by, but everyone without exception discouraged me from this idea. Only one person said, “Well, it’s dangerous, but if you walk quickly down the street, nothing will happen. Just don’t do it in the evening.” His words were enough for him to take the risk on a Monday morning.

The heart of the Old Town is the mosque Kebir-Jami.

This is the main mosque not only in Simferopol but in all of Crimea, built in 1508. That’s the very white mosque that the city is named after.

Next to the mosque is an Islamic store selling halal products and religious items. The streets of the old city are narrow and winding, and the houses are low and dilapidated. You might think you’re in the Middle East if it were not for the bright sign “Alcohol Market” right next to the mosque.

However, it’s hard to call it Russia.

Crimea is some kind of separate state, and the old city of Simferopol is even more so.

The condition of Akmechet is monstrous. Everything is falling apart here. The asphalt is shattered to pieces, the streetlight poles are crooked, a yellow gas pipe runs along the houses, the walls are cracked and crumbling, and cars pick at scattered scraps of crows.

How old are these houses? The earth has long been devouring them. Houses from the 16th century in the Middle East can look like this.

It’s probably the 1890s.

And this house could have been standing here since the 18th century.

The old city is beautiful. Akmechet reminds you of everything at once: Turkey, the Caucasus, the Balkans, and a village in Russia.

Yes, it’s really uneasy here. On Monday morning the city was empty, but even at this time, there was a group of three heavy drug addicts hiding around the corner of a residential building. The junkies clearly noticed me, but I quickly walked by and turned the corner, although I had time to get nervous. If it were evening, I would probably have been mugged.

Can you imagine being on this street without light?

The streets of the old city are long, winding, complex, and confusing like a maze. They loop for many kilometers. You can turn into the wrong alley and easily get lost. Here are walls on the left and right. Behind you are junkies, ahead of you are nameless poets. Not the best place for walks.

The King is naked

When I got home, I decided to search for the King on social media. Fortunately, he left his number and it was easy to find him. His real name turned out to be Rustam, but he introduced himself as Rostislav, probably out of love for all kinds of imperial power.

The King did receive a conditional sentence in 2019, but not for fighting with a cop, but for making a false call. Mr. Romanov, whose real surname is much less Russian, called 102 from his personal phone while intoxicated and told the operator that a bomb was planted at the Simferopol railway station.

Judging by his posts on Vkontakte, where in two sentences I counted three orthographic and four stylistic errors, the poet from the King is about as much of a poet as I am an archbishop. However, this does not negate his amazing knowledge of his hometown.