Dar es Salaam

Upon arrival in Tanzania, a visa fee of 50 dollars must be paid, and it can only be paid in cash dollars without change.

What if the tourist doesn’t have cash dollars without change? “Go to an ATM,” the reader will say. No, reader, there have never been ATMs in Tanzanian airports. “Ask someone to exchange it,” the reader will say. No, reader, you are the last in line, and all the passengers have already collected their luggage and left.

The correct answer: you need to ask the customs officer for permission to enter the country without a visa, find an ATM outside, withdraw money, and then return to pay and receive your visa. Now this is freedom! And you talk about Europe.

⁂

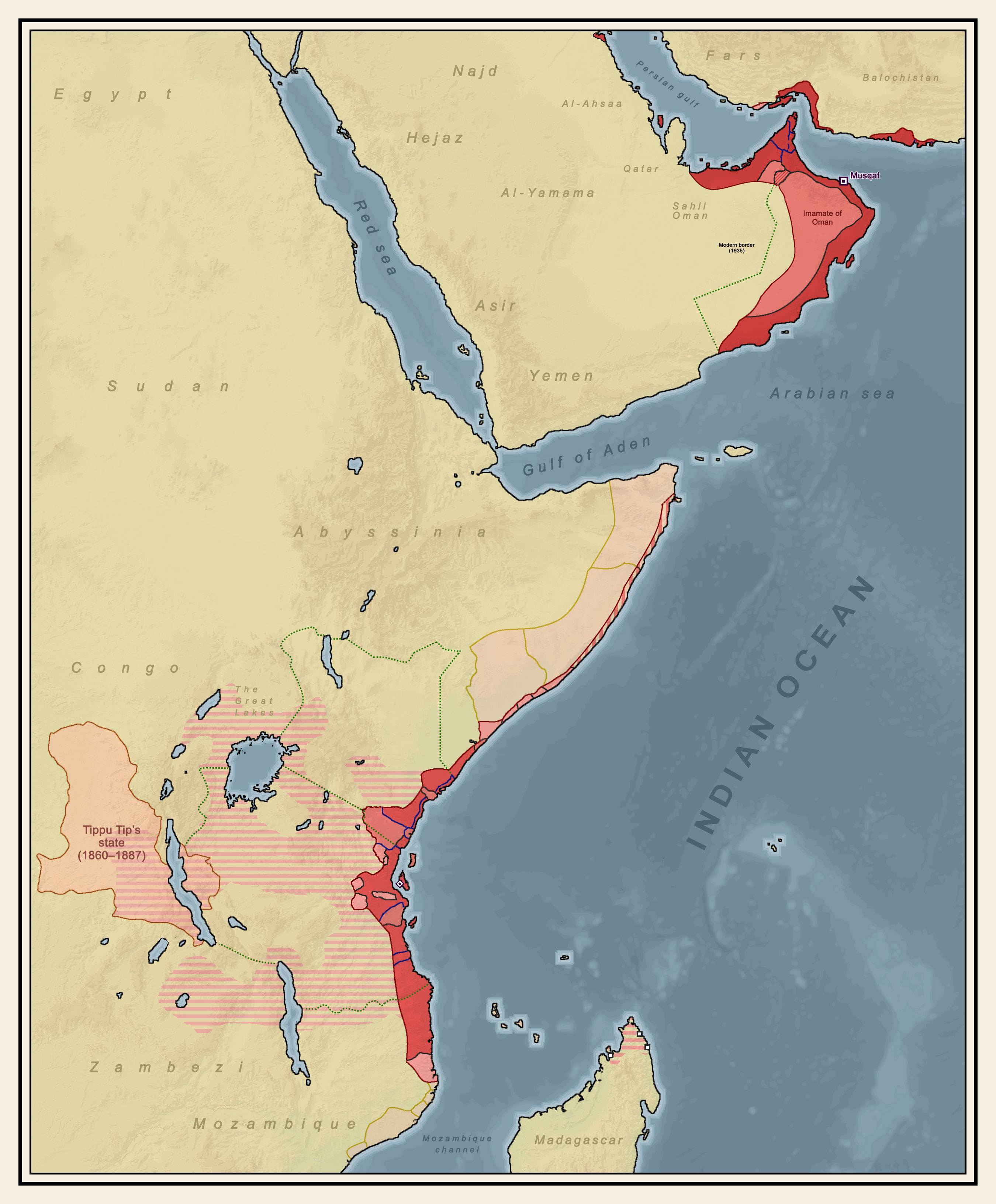

The capital of Tanzania is the city of Dar es Salaam. Translated from Arabic, the name means “House of Peace.” But what does Arabic have to do with it, if the city is in an African country? The fact is that at the end of the 17th century, the narrow coastal strip of East Africa was captured by the Omani Empire... no, not the Ottoman, but specifically the Omani — the same one from which a small country called Oman remains today.

It was the Omanis who founded the city of Dar es Salaam in 1862, where there had previously been a small fishing village. Interestingly, Oman took such a liking to African lands that it even temporarily moved its capital to the island of Zanzibar. It’s somewhat like if the capital of the US were located in Hawaii.

Today, Zanzibar is part of Tanzania. In fact, thanks to Zanzibar, the country is well-known today: it’s a popular resort and also the birthplace of Freddie Mercury. Typically, tourists stay in Dar es Salaam only for a transfer to the ferry that goes to Zanzibar.

However, the author is not a tourist, so we’ll skip Zanzibar this time and take a walk around Dar es Salaam. The capital of Tanzania greets you with road barriers that look like Soviet children’s footballs.

Unlike its neighbor Nairobi, Dar es Salaam turns out to be a rather pleasant city. In the center, there is a solid Catholic cathedral from the early 20th century.

This beauty was, of course, not built by the Arabs. At the end of the 19th century, the Omani Empire collapsed, and Tanzania came under German rule — it was the Germans who built the cathedral.

Five hundred meters from the Catholic cathedral, the same Germans also built a second cathedral, the Lutheran one.

Both cathedrals stand on the coast of Dar es Salaam. In fact, the area around them and along this coastline is considered the most expensive and elite district. In addition to the cathedrals, there are also several colonial buildings here that served various purposes.

An absolutely fantastic post office building was found. It was built by the British when Tanzania was under the rule of the British Empire. The architect is Peter Bransgrove, 1958. A rare genre: tropical modernism.

Bransgrove built many other buildings in Dar es Salaam. Not far from the post office, there is another of his works — a bank building. Most likely, the paintwork is modern, and originally the building was concrete. But it looks fine this way too.

Bransgrove was clearly no fool: he designed louvered walls to allow less sunlight into the windows.

Finally, along the waterfront and between these buildings lies a very pleasant park.

But for whom was all this built? Could it be that first the Germans, and then the British, selflessly developed the African capital? Not quite.

Although there was no apartheid regime in Tanzania like the one that existed in South Africa, Dar es Salaam was divided into districts based on race. Both under the Germans and the British, the city was divided into three parts: European, Asian, and African. The entire coastline and the adjacent elite districts were allocated to white Europeans. Asians (mostly Indians) were given the “second line” districts, which were more or less decent.

Africans, obviously, were left with the outskirts. They were not allowed to appear in European districts without a permit, which was issued only for work purposes: for example, if a Black person was a servant or a porter, they could come to work in the European district during the day. However, it was strictly forbidden for them to spend the night or live in the European district! Rare exceptions were made for local tribal chiefs and some church missionaries.

On the wall of the local museum hangs a map of colonial Dar es Salaam, as well as an excerpt from safety rules for whites:

The notice doesn’t explain how a white person ended up in Tanzania if it’s safer for them to “stay away from the native villages.” Colonial racism. Senseless and ruthless.

One way or another, racial segregation is a thing of the past today. The coastline of Dar es Salaam is now lined with high-rises, or as they are called here, skyscrapers.

It’s not that these skyscrapers are on the American level, but they look better than those in Kenya.

Among this business district, there is even a casino.

Sometimes you come across a view that you wouldn’t associate with Africa at all.

Throughout the city, there are an incredible number of examples of pleasant architecture. Modernist houses can be found here and there.

The most incredible building seems to belong to the NIC investment house. It was also designed by Bransgrove.

To protect the offices from the sun, the building seems to be wrapped in a cover with oval holes opposite the windows. This design was excellent at keeping out the heat long before air conditioners were introduced to Tanzania.

Even more interesting is that Tanzania was once a socialist country. Shortly after gaining independence from Britain, the then-president declared a course towards socialism.

Generally speaking, tropical socialism was quite mild: without the terror and totalitarianism found in North Korea. However, communists managed to nationalize banks and factories and introduced compulsory free education.

Of course, this didn’t last long: the country’s economy quickly fell into stagnation, which had to be addressed with European loans. Then the Soviet Union collapsed, and Tanzania’s own Gaidar implemented liberal reforms. Today, as a reminder of socialist times, one can occasionally find Soviet-style murals on the walls.

From a local skyscraper, you can also see several Khrushchyovkas, most likely built during the socialist period.

From above, the city center appears much more capitalist, yet still noticeably poor.

Squeezed between the “skyscrapers,” an old “mansion” charms with its naivety. The idea was New York, but the execution fell short.

Not far from the center, remnants of the Arab period can be found. However, this mosque might have been built later.

Two other mosques nearby are definitely newly built.

Despite its plainness, Dar es Salaam leaves a good impression. The city is somewhat cozy, even if it’s simple.

Another creation by Bransgrove instantly sets the right atmosphere: here we have something distinctly cultural before us.

Similarly, a randomly encountered colonial house nestled between new buildings pleasantly breaks up the African landscape.

The streets sometimes resemble Tel Aviv: there are many trees and greenery, plus simple concrete buildings.

A charming colonial bookstore.

An amazing library building.

Sometimes framed portraits are hung on the walls. It literally looks like street art.

The residential buildings are not exactly luxurious, but they’re clearly not dirty. There’s almost no trash in Dar es Salaam at all.

The city still has an Asian quarter, predominantly inhabited by Indians. Here one can find Hindu temples.

As for the people, things in Dar es Salaam are quite ordinary. The capital of Tanzania is not a tribal area, so one rarely encounters colorful characters here. Usually, people on the streets are busy with their own affairs: walking from somewhere, selling something, or transporting goods.

One of the colorful figures on the street is a woman carrying a load with a bucket or bag on her head.

And one of the points of contention is a monument in the city center, erected by the British in honor of African soldiers who served in the British Army during World War I.

This monument provokes intense debates among Dar-es-Salaamians. On one hand, it honors the memory of the soldiers. On the other hand, it seems like mockery: the British simply used Africans for their own purposes and then cast them aside.

And so, the residents of free Tanzania debate what to do with this monument. It seems like it should be torn down, yet it’s a pity. Such a good monument, after all. Made with soul.