The Tribes of the Omo Valley. Part Two: The Mursi

Getting to the Mursi tribe turned out to be far more difficult than visiting the Hamar. The bus station in Jinka had not a single car going to their village for some reason.

And there was no village either! Other tribes, although they live in huts in the middle of the savanna, gather around towns and villages like Key Afer. The Mursi are a completely different story. They are an entirely wild tribe with no major center. The Mursi live deep in the savanna, in complete isolation. Yes, they can be found on maps, and their homes are visible in satellite images, but... going to them on your own is a very bad idea.

One of the drivers finally explained why no bus goes to the Mursi. According to him, there were routes two weeks ago, but then... then a Mursi busted a local ranger with a rifle while he was riding a motorcycle. Therefore, all other tribes declared a boycott against the Mursi and imposed sanctions on transport communication with them.

This time, it was impossible to do without a guide. In fact, the author wasn’t planning to go to the Mursi alone anyway, so he arranged with a guide in advance. But what can he do if no one else is going to the tribe anymore?

After calling all his contacts in Jinka, my guide found a way to get to the Mursi village. All it took was hiring an armed ranger with his own vehicle.

The journey to the Mursi took several hours, during which at least two people asked the driver if he understood where he was going. The driver understood everything and kept his gun ready, while I, in the meantime, recalled the basics of probability theory. If one ranger was recently shot, is the likelihood of a second being shot higher or lower?

Along the way, there were groups of Mursi here and there, walking from somewhere to somewhere.

“Where are they going?” I asked the guide.

“Most likely to Jinka, they sometimes go there to the market to buy something.”

“Listen, we’ve been driving for two hours, and it’s scorching hot outside. Are they nuts?”

“Yes they are. Mursi is no joke. At least now there’s a road to them, and buses run... ran, until they shot the ranger. Before that, they walked on foot, and now they do again, until things calm down.”

“I understand that not many people get along with the Mursi...”

“People are afraid of them. They’re crazy. No other tribe wants to deal with them.”

The Mursi live in the most remote area of the Omo Valley, so they primarily engage in agriculture and make clay plates, cups, vessels, and ornaments. They rarely raise livestock. That’s why they walk to Jinka, where they buy meat at the market. And, of course, stock up on alcohol.

The walk from the Mursi settlements to Jinka takes more than a day. By the time one gets there, he can go crazy from boredom, especially at night. That’s why the Mursi never make it home with the alcohol they buy: they get drunk right there on the road. As a result, they’re prone to drunken fights and attacks on rangers.

“You see, we’ve been driving for so long, and not a single animal?” the guide continued. “It wasn’t always like this. Tourists used to be brought here for photo safaris.”

“There, look, monkeys.”

“Yes, only monkeys are left. The Mursi would get drunk on moonshine and out of boredom on way home, set the savanna on fire. Half the animals burned, and the other half they caught and ate.”

“They really do seem quite touched... Do they have any medical care?”

“They did. The government built them several hospitals and schools, just like for all tribes. But while the Hamar started studying, the Mursi simply burned down all the schools, and the doctors fled before they were shot.”

“Yeah, now I understand why you say Mursi is no joke.”

“The only thing they have left is there... see that cell tower? It’s still standing. That’s because it’s surrounded by barbed wire, and it’s made of metal. Metal doesn’t burn. Though, they might blow it up with something...”

Arrived. The first scene: ten thousand years before our era.

Yes, this isn’t the Hamar with their villages, markets, and T-shirts from China. This is a truly primitive tribe.

Faces don’t show joy at all. If I had come here alone, upon seeing such face expressions, I probably would have turned around and drive right back.

The Mursi live in straw huts shaped like domes. To prevent the house from collapsing in the first wind, the straw is usually mixed with clay and cow dung. There are no windows in the hut, and it stands on bare ground.

The structure underlying such a hut is incredibly primitive. It’s simply sticks stuck into the ground in a circle and brought together at the top to form a dome. It seems that this is what the very first houses built by humans looked like. We are looking at a living relic.

The entrance to the hut is not even a door, but rather a mouse hole that barely fits an adult. In the next photograph, the reader can see that the opening is scarcely larger than a person’s torso. Obviously, the entrance is made so small to protect against bad weather.

Inside the hut, there is literally nothing. The floor is compacted earth. A half-decayed log probably serves as a coach. Synthetic bags and plastic bottles are hung from the dome’s ceiling, and on the floor lies a decent woven basket, obviously traded by the Mursi at some market.

In another hut was the remains of a fire with an improvised hearth made of stones, as well as a thin blanket that served someone as a sheet.

The guide climbed into the hut with me and wanted to lie down on this blanket. He was already leaning back when something stopped him. There was a cover lying on the sheet, barely visible in the darkness, and underneath it was an object. The guide gently poked it: something soft. I turned on the flashlight, and the guide lifted the edge of the blanket. Underneath was a child’s body, showing no signs of life.

The child was alive, just drunk. Still, the Mursi don’t drink all the moonshine on their way back from Jinka. They save some for the village where they keep drinking, and pour some into their kids to shut them up.

Alcoholism has become the main problem for the Mursi tribe. After photographs of people with large plates in their lower lips made the Mursi famous, more and more photographers started coming to their settlements, hoping to win photo contests or appear in the pages of National Geographic. It were them who spoiled the Mursi by giving them money for photo sessions.

Rumors about white people walking around with black boxes on their necks and handing out money just for looking into these boxes spread throughout the savanna. After doing some brainstorming, the Mursi quickly realized that their socio-economic inequality could be addressed by exploiting the petty bourgeoisie. And started ripping off tourists.

Taking the idea further, the Mursi concluded that they could essentially stop working altogether and spend the added value gained from alienation of image rights... on moonshine!

It is said that since then, the Mursi have completely forgotten how to work. While neighboring tribes, such as the Hamar or Ari, raise cattle, cultivate land, trade in markets, and even sometimes engage in business, the Mursi tribe has turned into parasitic alcoholics.

Overall, the Mursi are a pastoral tribe. They raise cows and goats. Additionally, the covid pandemic forced them to return to their profession de foi for a while, as the flow of wealthy tourists was interrupted.

The reader may have noticed that in my photographs, except for the very first taken back in Jinka, I show only women and children. All the men have gone to graze cattle in pasture camps located many kilometers away from the settlements. They will stay there for several months.

The guide specifically asked and found out which settlement currently had no men. No one wants to encounter them, even with a rifle in hand: who knows what might come into the Mursi’s minds.

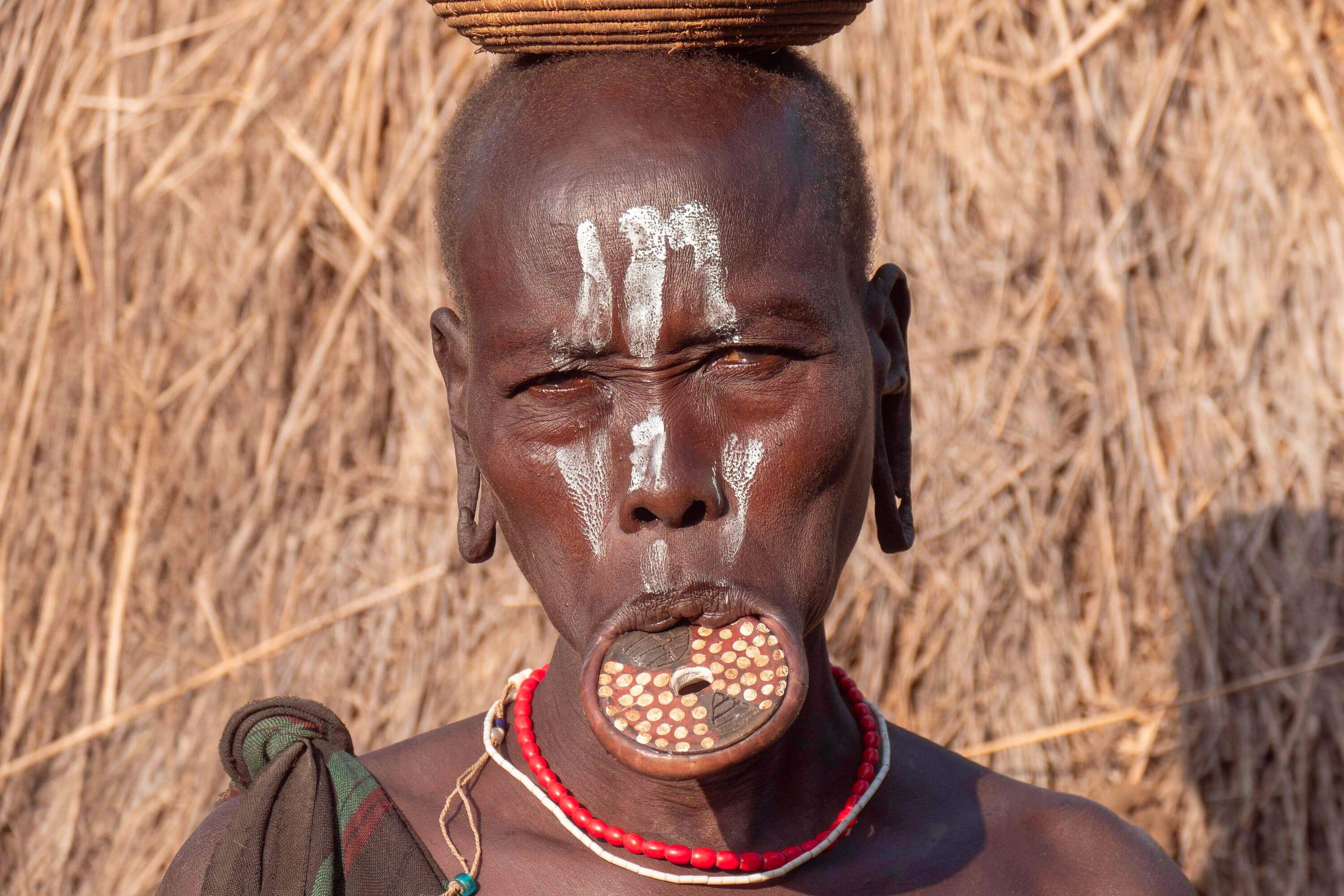

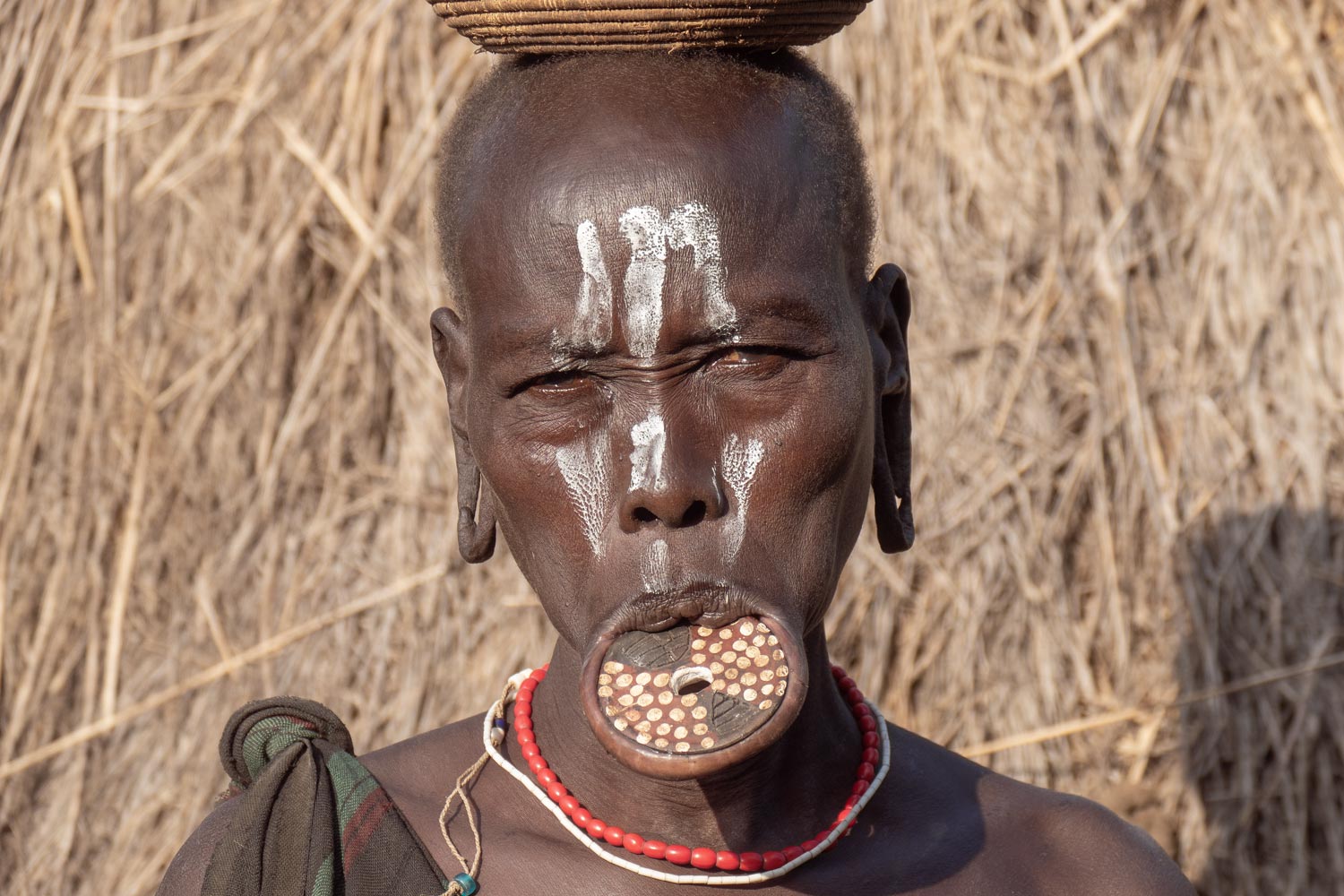

And in the next picture, it’s also a woman, not a “tribal chief,” as thinks everyone to whom the author shows this photograph.

Of course, all such pictures are taken for tourists in exchange for money. The Mursi do not wear these adornments every day. It’s a sort of “festive costume” — religious attire that they wear for various rituals.

It looks like this: the “standard package” of Mursi services includes photographing the tribe as a whole. For taking pictures of individual characters, like these women in full attire, one has to pay them separately. So they’re always ready. Dress up, stand by the hut, and call you over for a photo session. The guide comments, “separate fee for them.”

But what is truly true is the lower lip, which Mursi women begin to stretch starting at about fifteen years old, that is, a year or two before marriage.

First, a small incision is made in the lip, into which a wooden stick or a small disc is inserted. Every few weeks, a slightly larger disc is inserted into the incision, gradually stretching the lip more and more. This process can last over a year until the lip can accommodate a plate about fifteen centimeters in diameter. At that point, the girl is considered ready for marriage.

It is said that recently this ritual has begun to die out. Civilization, albeit slowly, is reaching the Mursi. Some of them move to Jinka and other villages, receive an education, and stop engaging in primitive practices. However, the Mursi are the most isolated tribe, so it’s likely that not much will change here in the next hundred years.

Strangely enough, the stretching of the lip is a voluntary process. In the tribe, there were several adult girls whose lips were intact. However, almost everyone had stretched earlobes, to such an extent that part of the ear seemed as if it had been cut off.

Indeed, the Mursi insert discs not only into their lower lips but also into their earlobes. Usually, these are not clay plates but wooden discs.

And while the lip is stretched starting in adolescence, the earlobes are stretched from childhood.

Terrifying beauty.

But the wild rituals of the Mursi don’t end there. Perhaps their bloodiest tradition is carving patterns into the skin, or scarification. The backs and arms of many Mursi are literally covered with scars in intricate shapes.

This ritual is performed by both men and women. Men usually scar themselves after winning a fight or killing an enemy, while women do it after their first menstruation or simply for beauty.

Scars are made using a blade or knife, first creating a wound in the skin and then rubbing ash or the juice of stinging plants, such as acacia, into it. When these substances enter the wound, they cause inflammation and slow down the healing process, resulting in a raised, firm, smooth scar — a source of beauty and pride.

Of course, the scars do not form a straight line but rather an intricate pattern. What exactly is encoded in it depends on various circumstances. Sometimes it’s something like a clan mark, while other times it’s a design that represents an event in a person’s life.

Well, enough of that. The Mursi also have more pleasant rituals. For example, mothers paint their children’s faces in the style of lip plates, drawing brown circles dotted with white spots on their cheeks and foreheads.

They also have a rare example of civilization. On one of the huts lay a solar panel. The guide explained that the government provided each Mursi village with a mobile phone and a solar panel to charge it.

The idea was to give the tribe the ability to contact a hospital in case of malaria or another critical situation.

Finally, the village even has a souvenir shop. The Mursi are eager to sell animal figurines carved from wood, as well as their famous lip plates.

The author bought one, but it didn’t make it to America; it crumbled in the backpack.

Races and IQ

The reader is surely wondering: are these “primitive savages” actually humans just like us? Would a child taken from an African tribe at an early age and raised in a European family, grow up to not a “backward native” but a normal person?

The answer is clear: yes.

Even if a tribe lacks writing, schools, mathematics, or logical games, this does not indicate primitive intelligence. Tribespeople are excellent at navigating the jungle, recognizing animal tracks, remembering complex routes, and hunting skillfully — all of which constitute their intelligence, which is essentially on par with that of a European person, just developed in a different direction.

To date, there is no scientific evidence that isolated tribes possess any genes that limit intellectual development. The brains of all humans are structured the same way. There are no significant differences in brain structure or volume related to ethnicity.

While the IQ of an individual can be influenced by genetics (for example, in the case of Down syndrome), the difference in IQ between groups is explained by environment, upbringing, culture, and nutrition.

The IQ metric itself is fundamentally flawed from the perspective of mathematical statistics, as demonstrated by mathematician Nassim Taleb in his work. The variation in IQ values within a group of people is significantly greater than the variation between groups. This fact makes all attempts to compare IQ between countries, peoples, or “races” mathematically void.

If we still do consider IQ, a meta-analysis of 62 adoption studies involving nearly 18,000 adopted children showed that children raised in adoptive families had significantly higher intelligence levels than their peers who remained in disadvantaged environments. In fact, their IQ was average for the population and did not depend on their origin.

As a master of technical sciences with a background in applied mathematics, the author quietly weeps when watching yet another video about “races and IQ” from a mega-influencer.

The ignorance of the 21st century is insidious because it disguises itself as science.