The slums of Kibera

“Are you staying at a hotel or do you live here?”

“At a hotel. I’m here, in Kenya, for a couple of weeks.”

“I see... so, how do you like it? Have you noticed that it’s very expensive here?”

“Hmm, not really. Well, how much am I paying?.. Let’s see. For ten days, three hundred dollars. That’s thirty per night. Well, it could be cheaper, but it’s okay.”

“Strange. Everyone complains, even expats. Are you wealthy?”

“Not at all. I’ve been traveling the world with just one backpack for almost a year now. We’ve got a war, you know.”

The waiter brought two plates of scrambled eggs with cappuccinos and placed them on the table. One portion was for me, and the other for my companion, a beautiful Kenyan woman with African braids neatly arranged on her head. Wearing a wrinkled red dress, she looked around nervously, examining the pristine interior of one of the best restaurants in Nairobi. Having breakfast in a shopping center of the prestigious district Kilimani is something not every Kenyan can afford.

“It’s my first time in a place like this. I’ve never been in restaurants. Is this a regular scrambled egg?”

“Well, yes. With sausages. And coffee.”

“They’ve arranged it so nice! It looks very tasty, but you could basically make the same at home.”

When the breakfast was finished, the waiter brought the check.

“You’ll pay, right? By the way, how much does it cost?”

“Eight dollars for the scrambled eggs and two dollars for the coffee.”

“Wow. That’s terribly expensive! I could never afford something like this.”

I paid in Kenyan shillings. My companion looked around the sparkling clean restaurant once more, touched her satisfied belly, and adjusted her hair.

“So, handsome, are you ready? Then let’s go.”

We left the restaurant and got into a black van where the driver was waiting for us.

“Ready.”

“Take off!”

Scramble for Africa

Kibera is the most famous slum in the world. Perhaps because slums rarely have a name, let alone such a simple one. Perhaps because this slum is considered the largest in Africa and one of the largest on the planet.

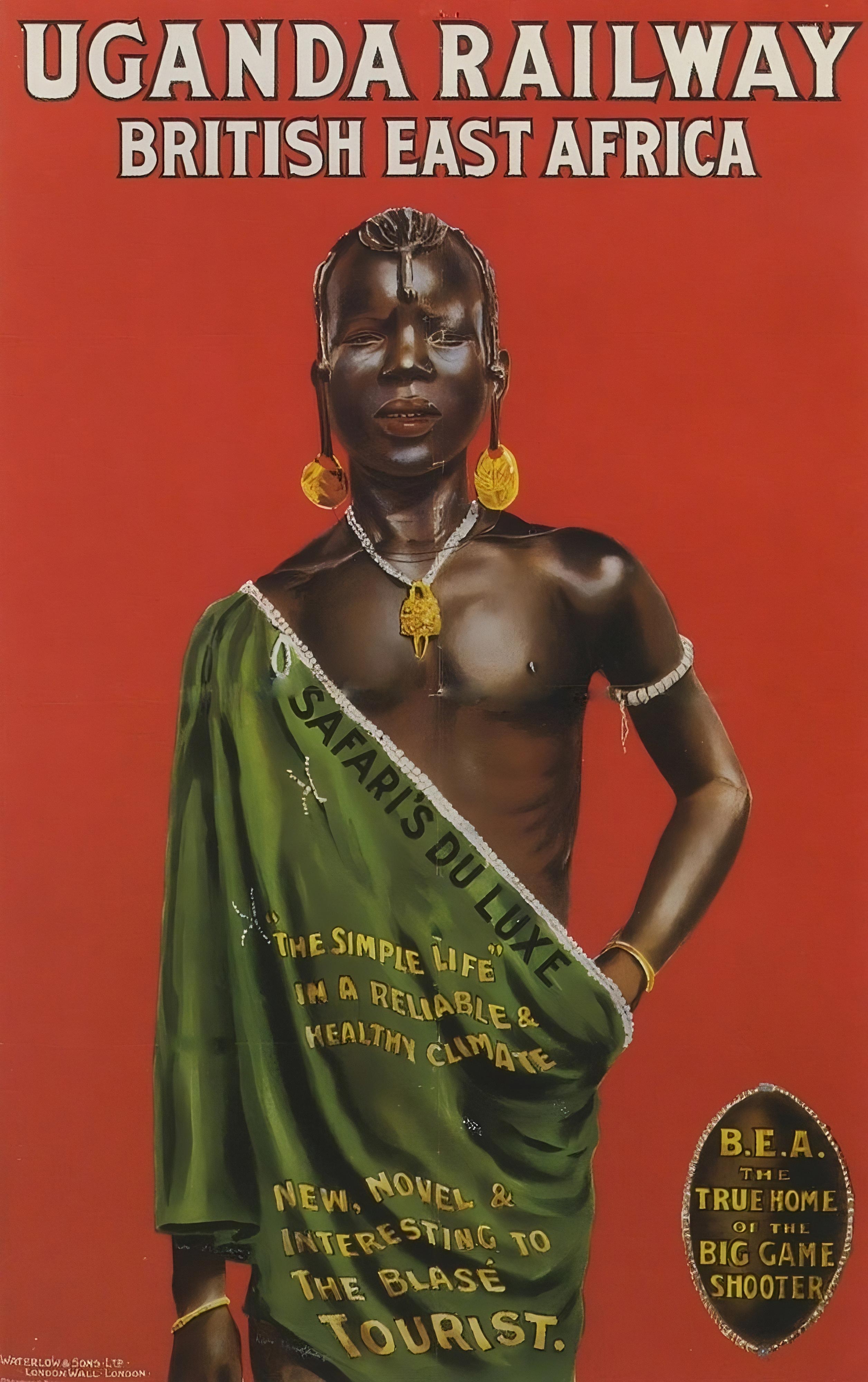

The history of Kibera is sad and prosaic. At the end of the 19th century, seven European powers were fighting for control over Africa. One of the main players was, of course, the British Empire, which firmly took hold of East Africa and colonized Egypt, Sudan, Somalia, as well as Kenya and its neighbor Uganda.

However, while Kenya could be easily controlled due to its access to the sea, Uganda was located almost in the center of Africa. To prevent losing it to Germany, the British needed to establish supply routes. They took on this task by building a railway that connected the city of Mombasa on the Kenyan coast to Lake Victoria, from where the further route to Uganda continued by water.

This colonial war went down in history as the “Scramble for Africa.” Britain and France emerged as the winners, while the German Empire lost in the scramble and disintegrated after World War I.

The city of Nairobi, the future capital of Kenya, emerged as one of the stations on the Uganda Railway. Before the British, there was no city here, only swamps and pastures of the Maasai tribe. Thus, Britain created modern Kenya along with its capital Nairobi literally from scratch. The downside of colonization, however, was the emergence of slums on the outskirts of the new city.

To build and then maintain the railway, the British brought in migrant workers who settled right next to their workplace. After the project was completed, some of the immigrants returned home, while others stayed near the railway tracks and found new jobs. Later, they were joined by Nubian soldiers who had fought on the side of Britain, and the government allocated land for them to live on the outskirts of Nairobi.

First the influx of migrants, then the influx of black soldiers, and later the influx of other settlers from poor areas led the British to anticipate social problems. Therefore, they decided to engage in the favorite activity of white colonizers in Africa — racial segregation.

To prevent black people from bothering whites, the British divided Nairobi and its outskirts into ethnic neighborhoods and introduced a pass system. Living in the better areas of the city now required a special permit, which, with rare exceptions, was issued only to whites. Additionally, the British enacted an anti-vagrancy law, under which all homeless people were expelled from the capital beyond the settlement boundaries.

All of this together led to the creation of giant slums on the outskirts of Nairobi, where the poor and homeless from all over the city began to gather. By that time, the first immigrants and Nubian soldiers had already settled in the area and even managed to give it a name. They called it “Kibera,” from the Nubian word “kibra,” which translates to “jungle.”

It turns out that the Kibera slums, where we are about to go, is not a result of “African backwardness”. This is a result of Britain’s colonial policy and a living monument to racism, which has survived to this day and may well outlive us.

Kibera

The slums begin with the very Uganda Railway, which is a narrow-gauge track one meter wide — the cheapest and most effective solution for colonizing a foreign continent in the 19th century. The railway is still used for freight trains, but they pass through here quite infrequently.

Following the railway, begin typical settlements, similar to those the reader might have seen in the story about Bangladesh.

Kibera shares many similarities with other slums. For example, the streets here have the same piles of garbage as in Cairo’s Garbage City, which are similarly eaten by local goats.

Sometimes there is so much garbage that it covers an area the size of a football field.

The housing in Kibera is reminiscent of another place. It most closely resembles the Dharavi slums in Mumbai. While in Bangladesh people live in huts made of wood, straw, and plastic bags, in Kibera most homes are made of iron.

Obviously, these homes do not have air conditioners. They probably don’t always even have fans. Fortunately, the climate in Kenya is not too aggressive, but temperatures sometimes reach up to 30 degrees Celsius — and then being in such an iron house must be unbearable.

Add to that the fact that some houses have windows facing directly onto a garbage dump. It’s frightening to imagine what kind of scent pervades Kibera homes in the summer.

In Kibera, there are also clay houses. To be more precise, it’s not even clay but an incredible mixture of sticks, straw, and dirt, assembled into something resembling the shape of a house. Only the roof of such a house remains made of iron. This is actually a good thing, as it at least prevents it from being washed away by rain.

The houses are typically one- or two-story, and the doors open directly onto the street. Fancy. Almost like in America.

In front of almost every house lie large wooden planks. Just like drawbridges at castles, they are laid across ditches where, instead of crocodiles, float piles of garbage.

Indeed, iron housing is not the biggest problem in Kibera. The sewage is a far more frightening issue. There is no regular garbage collection, so residents either dump waste at their feet or burn whatever can be burned.

Fortunately, in most parts of Kibera, the smell is fairly tolerable. The worst situation is for those living near the local river, which carries such an odor that it makes you physically ill to be close to it.

It seems that the locals have long since gotten used to it and don’t notice even the strongest smells. Just a meter away from the garbage-filled river, one can find fish for sale in the open air. Dust and splashes land on it, and of course, flies settle — the ones that have just been feasting on the waste flowing in the river.

One can only hope that the fish itself wasn’t caught in the same river.

Medicine and Economics

Is there any doubt that the population of Kibera suffers from a wide range of diseases? Here they have cholera, pneumonia, diarrhea, tuberculosis, intestinal infections, and HIV/AIDS.

Collecting statistics in such slums is extremely difficult because even post-mortem diagnoses are not always accurate. Some figures indicate that 12% of the population has HIV, and 30% suffer from norovirus. Additionally, every fifth child under the age of ten has had typhoid fever at least once, a disease Europe hasn’t heard of since the mid-20th century.

Other figures show that 34% of children under five die from pneumonia, while among adults, the highest mortality rate is from AIDS, which claims the lives of over 18% of Kibera’s residents.

However, over the past ten years, mortality rates have decreased. Through the combined efforts of the WHO, the Red Cross, American foundations like the CDC and USAID, as well as Kenya’s Ministry of Health, mass vaccination and the distribution of free antibiotics were initiated in Kibera. As a result, mortality from pneumonia has dropped threefold, and from tuberculosis almost fourfold.

Today in the slums, one can find pharmacies and medical centers, many of which operate on charitable contributions.

Some of them even have modern equipment and conduct laboratory tests.

Unfortunately, intestinal infections are not so easy to defeat. Treating them every time is exhausting, and there is no vaccine for all sorts of things like norovirus. To eradicate this bastard, one needs access to clean water and proper sanitation — prophylaxis, in other words. But how can all this be provided in the slums? It can’t. So for now, in Kibera, people draw water from taps sticking out in the middle of the street. That’s in the best case. In the worst case... don’t even want to think about what kind of water they drink here.

Most Kibera residents cannot afford clean water and good nutrition. The average “income” in the slums is only one or two dollars a day. Out of this, about ten dollars a month goes to housing. Another five dollars go to electricity, which is paid not even to the government, but to local gangs that have run illegal wires from the power lines. It’s an expensive affair. And since there is no gas in Kibera either, cooking is usually done over charcoal.

Despite this appalling poverty and unsanitary conditions, people in Kibera do their best to remain dignified. They are not drunkards, junkies, or degenerates. These are people who fell into a deep social pit decades ago and cannot climb out despite all their efforts.

And this is evident from the first steps in Kibera. A visitor will not see drunken people lying around or beggars asking for alms. Oh no, people in Kibera are busy with work! The slums have their own economy, albeit a very primitive one. There are bars, barbershops, shops, pharmacies, and even internet cafes.

The most surprising sign of all is “Hotel.” Of course, there are certainly no hotels here. For some incredible reason, in Kibera, ordinary eateries are called hotels. It must be a local joke.

Painted on many doors is another sign: “Pub.” Sometimes, beneath it, appears a proudly misspelled note: “Take a way.”

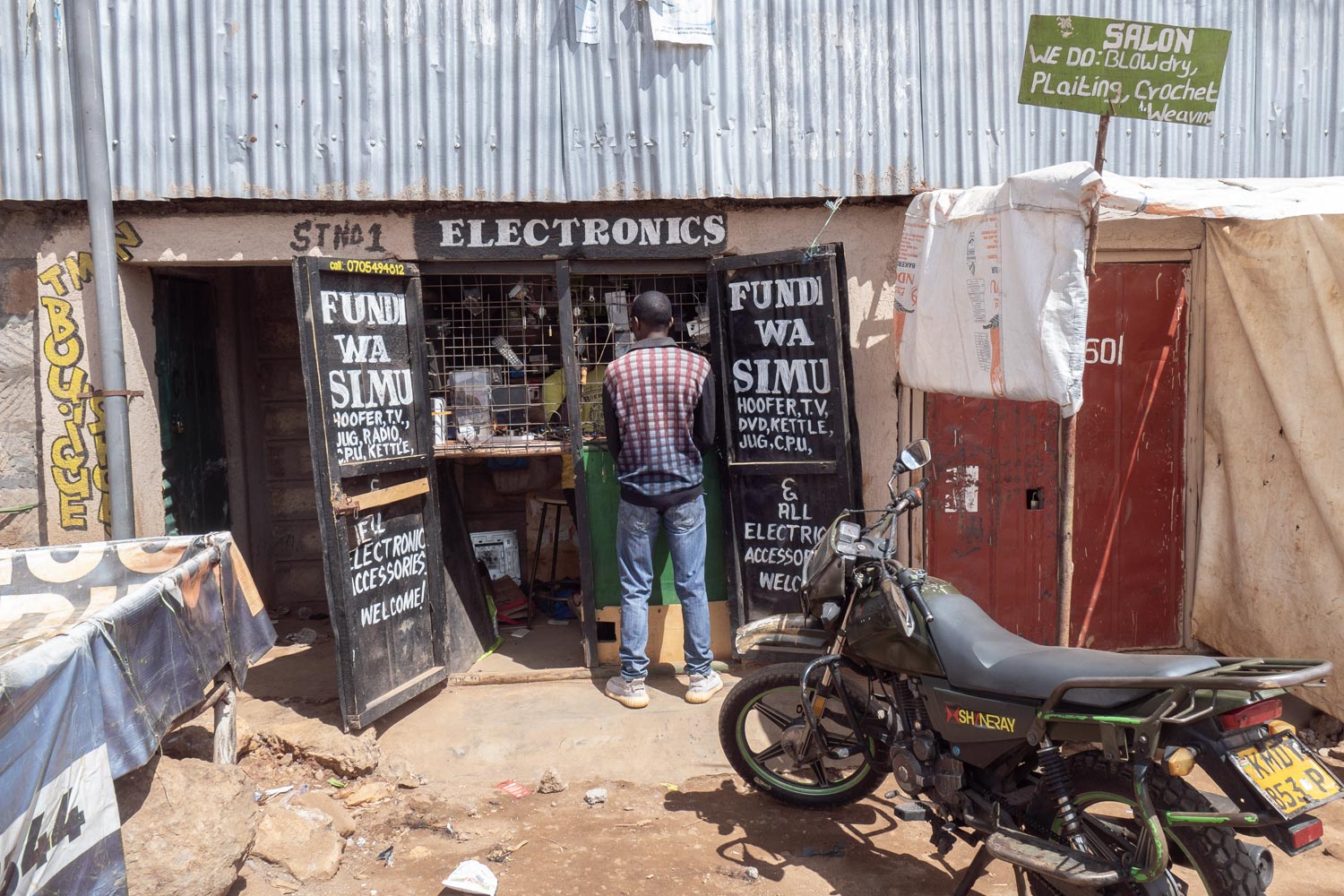

Kibera also has electronics shops. This sign should be taken literally: such stalls sell wires, remote controls, speakers, microchips, and other technical scraps, not televisions or computers.

Most commonly, one’ll come across SIM card shops, which are usually also decorated with the brands of Kenyan mobile networks. Judging by the neat logos, Airtel has likely distributed special stencils and paint in Kibera.

On virtually every street in Kibera, one’ll find a beauty salon or barbershop. By the way, the reader might have noticed that all the signs are in English. That’s correct: almost everyone in Kibera speaks English, as it is an official language of Kenya alongside Swahili.

Kibera’s small businesses go further, offering services such as photocopying, laminating, mobile internet setup, and equipment repair.

According to statistics, unemployment in Kibera is over 50%. But this figure means nothing because the concept of “permanent employment” doesn’t exist here. Nevertheless, most people are engaged in something.

Some people sell candies and snacks.

Some people sift millet and sell it.

Some people clean and sell fish.

Kibera has its own clothing shops.

There are also carpentry workshops here where they make their own furniture, as well as repair, paint, and varnish it.

Although the average Kibera resident indeed lives on a couple of dollars a day, there is a sort of middle class among them.

The most successful people in Kibera work in taxi services and delivery. That’s why cheap motorcycles, such as the Bajaj Boxer, are so popular in the slums. A used model can be bought for around $500. It’s a large sum for a slum resident, but it’s manageable.

Obviously, motorcycles require maintenance, so there are workshops and cleaning services operating in Kibera.

Motorcycle owners dress differently too. One can tell: middle class!

Cars are much less common. Typically, they are very old Toyotas, sometimes from the 1990s, with strange logos. These cost between three to five thousand dollars. That’s a very significant amount for Kibera, so a car is usually purchased by a family, often on credit and for a specific purpose.

Children of the Slums

How many people live in Kibera? In general, we cannot know this because slums, by definition, are informal settlements without property registration.

The numbers vary. It was once believed that Kibera had either 500,000 or 2 million residents. Then Kenya conducted its own assessment, and it turned out the slum’s population was no more than 170,000. A more recent estimate suggests about 250,000. That’s still an incredibly large number, but at least it’s not millions.

The Kenyan authorities have been trying to resettle Kibera since 1920. All attempts failed because the “resettlement” was carried out in the best traditions of Africa — simply demolishing some houses and evicting people. Naturally, people returned and rebuilt everything anew.

Not long ago, Kenya launched a national slum resettlement program, this time starting with the construction of housing. However, this program is also struggling. The new housing turned out to be extremely affordable but not free, and residents had to pay officially for electricity and water.

As a result, the renovated areas were unaffordable for local residents, and the new apartments quickly ended up in the hands of officials and their sons. Instead of being resettled, the unfortunate Kibera residents were pushed even deeper into the slums. This phenomenon is called gentrification and often occurs when attempting to redevelop poor areas.

No matter how many people live in Kibera, dry statistics won’t tell you anything about them. Meanwhile, the “slum population” is not a faceless mass. These are real people — each with their own story — who study, work, start families, have fun, and take care of themselves to varying degrees.

A random passerby on the streets of Kibera can look as stylish as a member of a subculture in New York. It leaves one to wonder whether they consciously created their look or simply threw on whatever they could find.

The most dramatic part of Kibera is the slum children. Behind their appearances lies an entire story. Some are forced from a young age to care for their younger siblings, literally carrying them on their backs.

Some, as early as six years old, already have adult features appearing on their faces.

Children in Kibera do have a childhood, but it’s a difficult one. Very often, children work from a young age because their parents can’t support them. However, this doesn’t mean their entire childhood is spent working: slum children manage to find time for work, study, and play.

Of course, there are no playgrounds in Kibera. Children have to play right in the middle of the trash.

And still, children remain children. Smiles are more common on their faces than sadness.

School

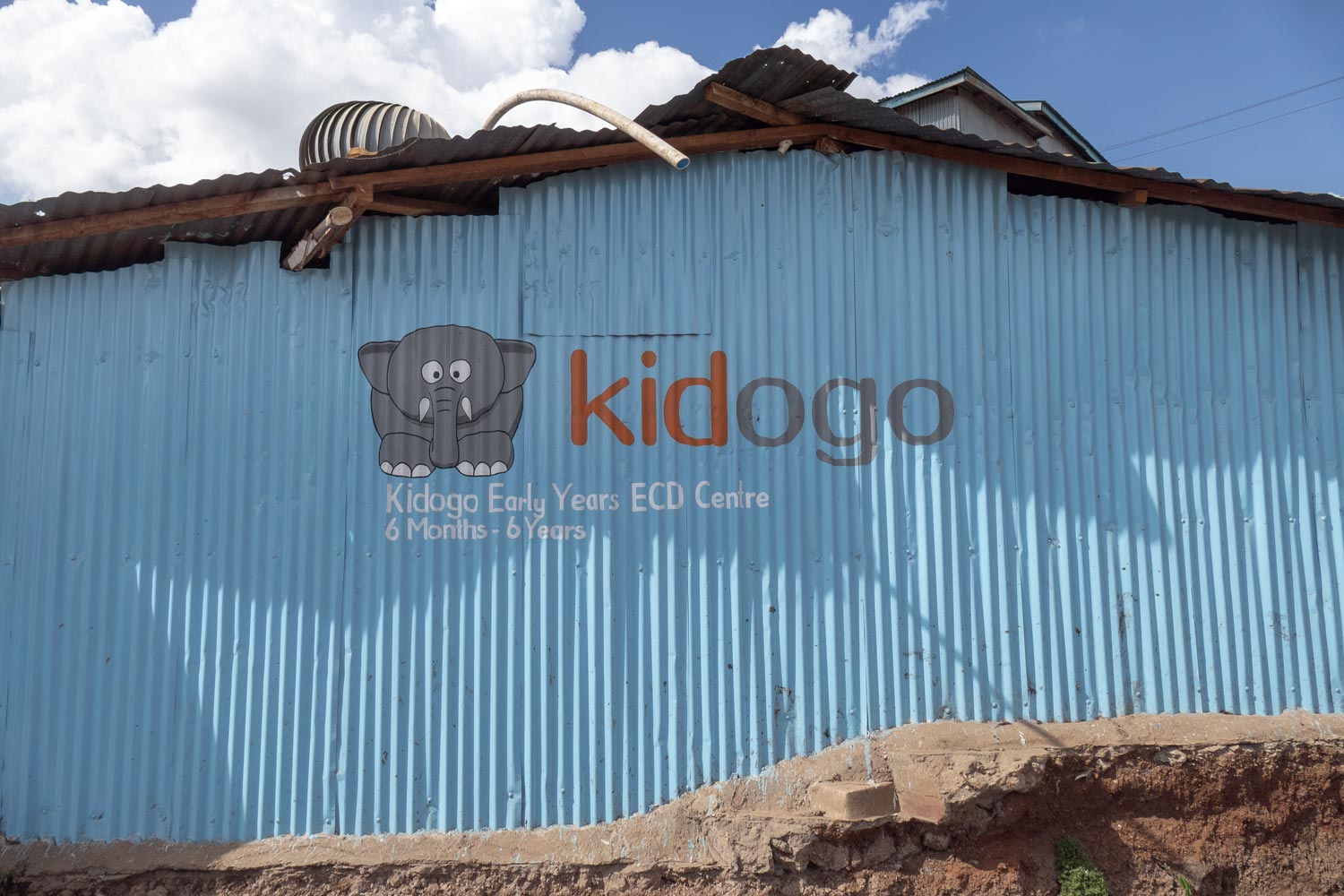

Although the story of Kibera is one of social failures, some measures have worked. For example, a kid’s center has been built in Kibera where children up to 6 years old are taught.

It turns out that there is an exceptionally decent school for girls in the slums.

Not far from the girls’s school, there was a general school. My companion, a beautiful Kenyan woman, approached the school’s door and opened it, letting in the students who were waiting for her.

“I work at this school. It’s called Seed School... like, a seed of knowledge.”

The school turned out to be a gray, shabby building made of concrete blocks of terrible quality. Upon entering, a visitor is greeted by a dirty, narrow corridor with grimy, scratched walls and a small poster on the crossbar: “Keep calm and practice English.”

In the corridor, there’s also a class schedule on a sheet of poster board stuck to the wall with large pieces of tape. It shows that school runs from 7 AM to 2 PM with two long breaks for breakfast and lunch. One of the schedule slots is labeled “Free choice,” and another is “Health Check,” which is conducted daily and takes 20 minutes.

“We try to spark the children’s interest in learning. The situation in Kibera is very difficult. Children often work because if they don’t, their families might not make it. So, they don’t always have the opportunity to study, and if learning isn’t enjoyable, they will just scatter.”

“I see that breakfast and lunch are on the schedule. Do you really feed the children? That’s amazing.”

“Yes, we do feed them. And, you know... that’s another reason why children come to school. Sometimes, apart from the school meal, they don’t eat anything else all day...”

“You mean to say that the children here are starving?”

“Not exactly starving, more like... well, they don’t eat enough. They don’t have regular meals. Children from poor families don’t always eat three times a day. Sometimes they eat at school, come home in the evening, and there’s simply no food, so they have to wait until morning.”

“That’s what’s called to starve... At least nobody dies of hunger here?”

“No, they don’t die of hunger. We get help from organizations in America and Europe. This girls’s school, for example, is funded by Beyoncé. And our school is part of the Seed program from Canada. We receive grants that are entirely used for teachers’s salaries, books, and food for the children... Yes, and this is where the classes are held. Come on in.”

The classroom turns out to be as gloomy as the corridor. It doesn’t even have proper windows, just narrow slits near the ceiling covered with grilles. The chalkboard is propped against a wall adorned with colorful sheets featuring charts and drawings. The chairs are roughly assembled scraps of wood in the shape of a chair. The desks are terribly worn, and it’s easy to get a splinter in your finger from them.

“This is how they learn. It’s not much, of course, but it’s all we can afford for now.”

“What subjects do you teach?”

“Different. We try to provide the children with basic knowledge about the world. In the early grades, we teach mathematics, English, and biology. It’s important to explain to the children from the start how the body works, that, for example, you shouldn’t eat with unwashed hands, and how crucial it is to follow hygiene. That’s the only way to defeat epidemics. Look, here’s a poster; it shows the body’s structure and it’s in English.”

“And this is for the middle grades. Here we have geometry, where the triangle is. To the right of it is a diagram of how a ballpoint pen works, which is part of physics. Below are food products, and at the very bottom is quite complex: diagrams of the heart’s function and the reproductive system.”

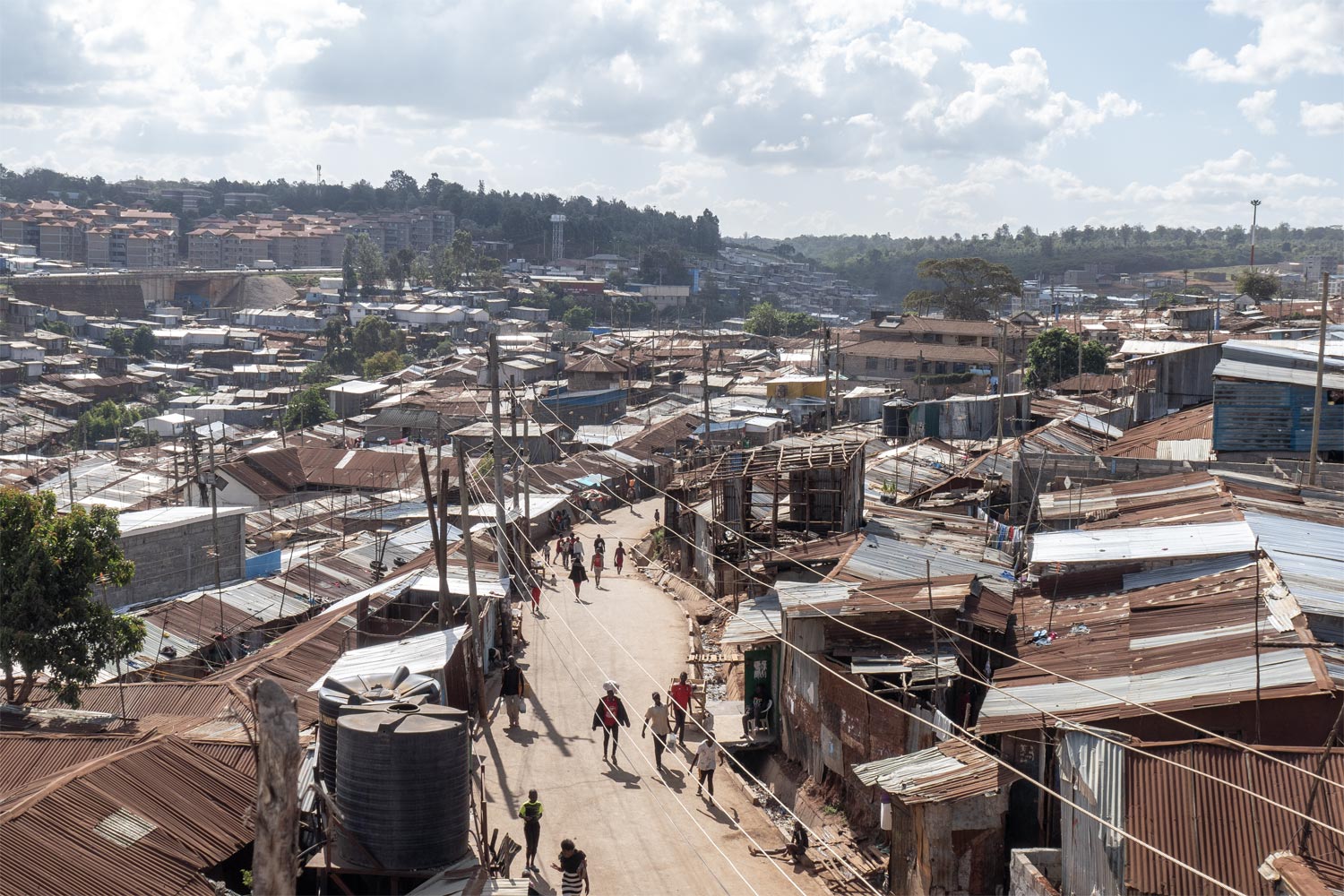

After showing me a couple of classrooms, my beautiful Kenyan companion, who turned out to be a primary school teacher, led me up several flights of stairs. I stepped onto the school roof and from there saw all of Kibera laid out before me. The rusty roofs of the tin shacks stretched almost to the horizon, reaching towards the distant skyscrapers of Greater Nairobi.

Somewhere below, people were walking along the dusty road, casting long pre-sunset shadows that resembled unknown wanderers.

In the gap between the shacks, was visible a blooming, green football field — the only vibrant spot amid this rusty swamp.

The Kenyan woman touched my shoulder:

“So, handsome, do you want to meet the kids? We have a music class here.”

We went down a floor and entered one of the brightest rooms in the school. It had a window that spanned half the wall, making even the gray-brown walls seem less gloomy and somewhat enlivened. I was seated on a chair, and five children were brought to the center of the room. Glancing around, I saw a cassette player sitting on a chair in the corner.

“Oh, no! Don’t tell me they’re going to dance for me!”

“Everyone gets embarrassed. They think I’m torturing the kids! No, they are very happy with all the visitors. They love to dance.”

With these words, the Kenyan woman turned on the music, and I froze in horror. For the next few minutes, I was given a performance by five black children who clumsily danced to African rhythms in front of the “white master” slumped in the chair.

“Do you have something to give them?”

“What, to give? In what sense? Money?”

“No, they don’t need money, they’re children! Do you have a cookie?”

“Uh, yeah... I have a Snickers here...”

“Give it to them. Just tell whoever you give it to that they should share it with everyone.”

I took a crumpled Snickers out of my pocket, with two pieces in the package, and gave the children first one piece, then the second, gesturing that they should be divided equally among everyone.

“They won’t eat it now. They’ll save it for the evening in case there’s no food at home.”

“I think the kids are tired. They’re barely dancing anymore. Let’s wrap it up; I feel awkward watching all this.”

“Alright, let’s go. Kids, bow and say thank you!”

“Oh, no, that’s not necessary! It’s fine, it’s fine.”

⁂

The entire way back, I traveled in silence. What is there to say? In the slums of Kibera, it’s not outcasts, drunks, junkies, or “genetic waste” that are trapped. Here live hardworking people, many of whom want to learn and work, but they can’t because they got caught in a vicious cycle several decades ago.

Toward the end of the trip, I finally decided to say something.

“You know, I was looking at the GDP growth statistics for Kenya. It’s the fastest-growing country in Africa. The economy is growing by 7% a year. If this continues, Kibera will dissolve in about ten years.”

“These talks have been going on for many years, Andrew. I hope you’re right, but for now, it’s just a dream.”

“No, really. There used to be similar slums in Vietnam, but they dissolved. I know economics! I can assure you that Kibera won’t be here much longer!”

The Kenyan woman smiled indulgently. When I asked about safety in Kibera, she assured me that I could probably go into the slums alone but would likely get lost. She then added that one should never do that. After all, the twenty dollars I paid for the tour would go towards the development of the school and meals for the students. It’s a small price for a European tourist, but a giant help for a resident of the slums.