Hebron

“Are you going to Turkey? Take a car to Kurdistan!”

“When you’re in Jordan, go to Iraq!”

One day I told him that I was going to Palestine:

“Stay away from Hebron.”

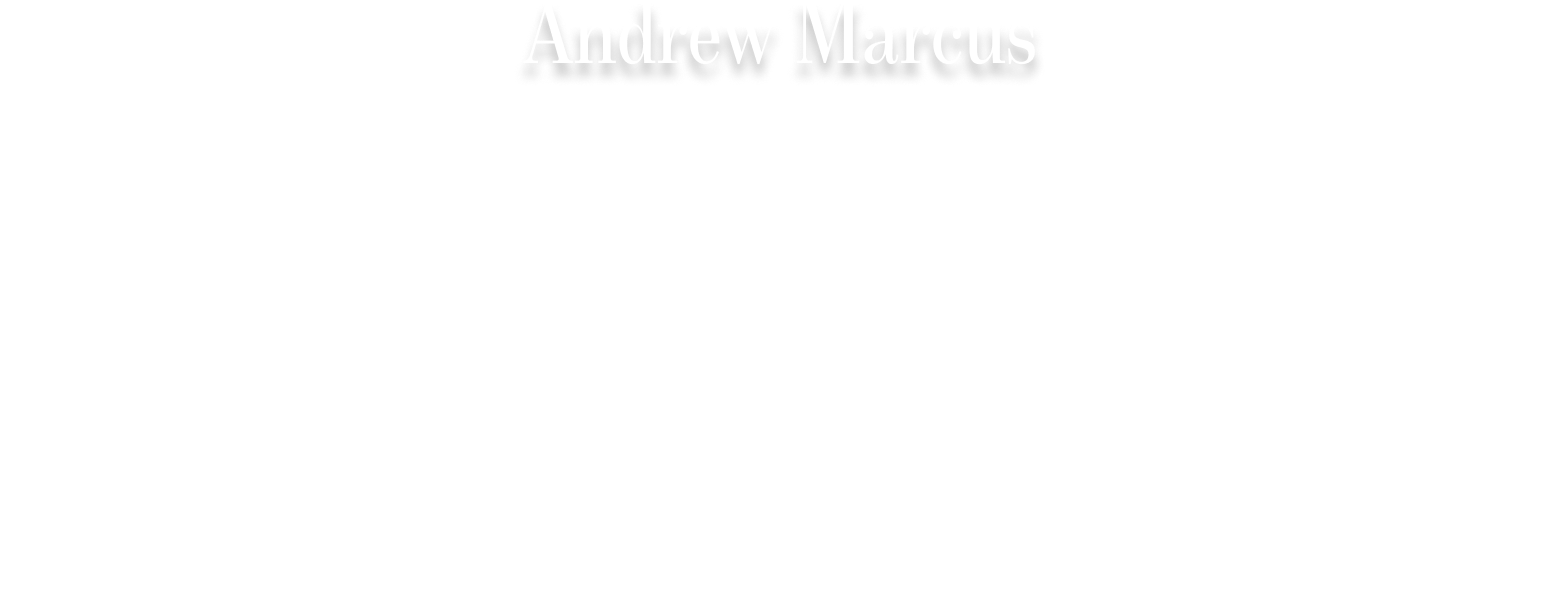

Palestine is not a unified state but a fragmented territory divided into three zones.

In Zone A, only Arabs live, and Israelis are not allowed to be here without a special permit — it is an undisputed Palestinian territory. In Zone B, everyone is allowed to stay. And finally, Zone C is only for Israelis and passage of Palestinians.

When talking about the occupation of Palestine, they primarily refer to Zone C. It is precisely Zone C that divides the unrecognized state into fragments, creating significant problems for living and moving around the country. For example, in Zone C, Palestinians are prohibited from building anything without special permission from Israeli authorities. Naturally, obtaining such permission in practice is simply impossible — 95% of applications are rejected, while Israelis obtain permits without any issues. Moreover, Zone C contains the majority of Palestine’s natural resources: fertile land, forests, minerals, and water.

And this land, to which people have no access, occupies more than half of all Palestine. Let’s look at the map: the beige patches represent Zones A and B, while the vast blue territory in two shades is Zone C. This is what Palestine looks like. A country torn into pieces!

It’s not so difficult to imagine such division on a country-wide scale, but what about a specific city?

Hebron is divided in a unique way, different from the rest of Palestine. One quarter of the city is separated into a special zone called H2, designated specifically for Jews. The remaining part of the city is occupied by Palestinians and falls under Zone H1. Along the border between the two zones, right in the middle of the city streets, there are checkpoints with armed soldiers who restrict free movement across the border.

What is it like to live in an ordinary city that is divided in half? To undergo searches in the middle of the street? To be unable to access certain former schools, markets, and shops?

It is almost impossible to reach Hebron directly from Jerusalem unless traveling with a Palestinian in a car using some clever bypass routes. There are no direct buses or taxis available because the road to Hebron is blocked by the Israeli wall near Bethlehem, and passage through Zone C is only possible by bus until the small settlement of Kiryat Arba.

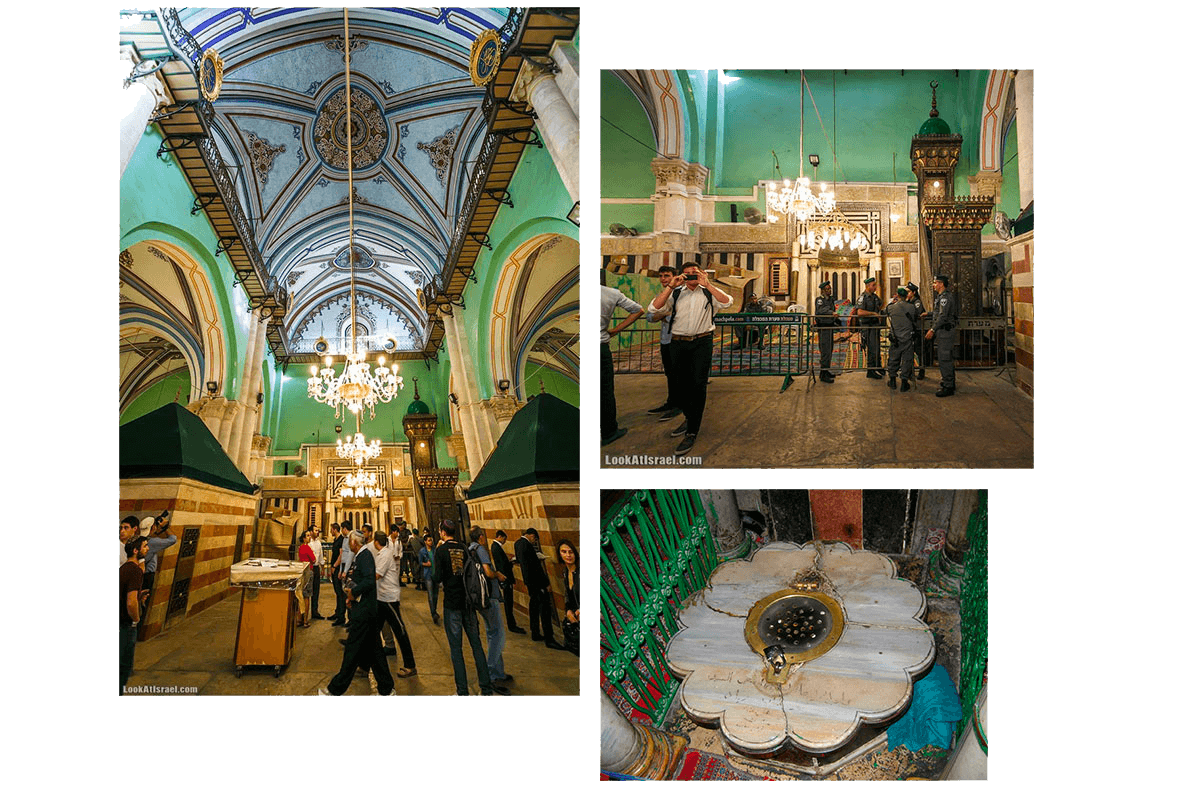

Kiryat Arba is one of the early Jewish settlements established in Palestine. It is an extremely volatile place located very close to Hebron. Constant acts of terrorism and violent clashes occur here between Israelis and Palestinians. Kiryat Arba holds strategic importance. Similarly to Bethlehem, Hebron is home to one of the holiest sites in Judaism. Jews refer to this place as the Cave of the Patriarchs (Mearat HaMachpela), Arabs as the Mosque of Ibrahim, and Christians as the Cave of the Patriarchs.

Kiryat Arba

The bus arrives in Kiryat Arba, and the first encounter with Hebron and its horrors begins right here. Figuring out how to proceed into the city from this point requires some guesswork. Travel guides don’t provide too many details about the entire route, and the area is far from being tourist-friendly.

Before traveling to Hebron, it would be highly advisable to thoroughly familiarize oneself with this place. It’s not at all like Bethlehem, although it might seem that way after visiting Bethlehem: how much more intense can it get? But the problem lies in the fact that almost nowhere is it described what Hebron truly represents. Only dry facts stating that the city is divided into two parts. Well, it’s divided, so what? The whole country is divided.

“Where are you guys going?” Suddenly, Russian speech is heard from behind.

“To Hebron.”

“Oh-ho-ho, to Hebron! What brought you here, for heaven’s sake?”

By chance, the passerby turns out to be incredibly charismatic: a middle-aged man in a checkered shirt and driver’s cap, thickly bearded, carrying a crumpled bag of groceries from a supermarket in Jerusalem, wearing ridiculously oversized glasses with double lenses.

“But why are you heading to Hebron? Today is Friday, and with sunset, the Sabbath will begin. I remember there was some order not to let foreigners into the Machpelah before the Sabbath.”

“We heard something like that, that’s why we’re in a hurry. By the time the bus arrived in Kiryat Arba, it was already quarter past three, and the sun sets just after seven. We had to explore everything before sunset to avoid wandering in the military zone at night.”

“Well, don’t rush. Do you even know anything about Hebron? How to get there and what to do there?

The character’s name was Israel Lugovsky, and he turned out to be a former Soviet migrant who left during the perestroika era. Probably because Lugovsky was a professor and the author of several articles on linguistics, his story about Hebron turned out to be so intricate that we had to spend a whole hour listening to the intricate plot twists between the Strugatsky brothers’ novel and the ballad about the terrorist Baruch Goldstein.

Baruch Goldstein. If the reader has only heard of Palestinian terrorism until now, then this name is the most prominent among Jewish terrorists. Once in 1994, a local doctor, an American immigrant, Dr. Goldstein stormed into the Cave of the Patriarchs and opened fire on the praying Muslim crowd. In this act of terror, 30 people were killed and more than 150 were injured, after which Goldstein was knocked down with a fire extinguisher and beaten to death with iron bars.

Lugovsky told scary and convoluted things about Hebron. He personally knew Baruch Goldstein’s father and, it seems, even knew the terrorist himself but chose not to talk about it. His close friend was ambushed and killed by Palestinians somewhere there, between those huts along the way to the city, which happened to be the exact route marked in the navigator.

“What a pity, guys, that you didn’t call me earlier!”

“Well, who knew you were here?”

“Ah, yes. I wish I could have shown you around Hebron. I would have shown you the Cave of the Patriarchs, all those places where the massacre happened, where my friend was killed... By the way, here, behind the fence, is Goldstein’s grave. They wanted to bury him in the old Jewish cemetery in Hebron. The military authorities opposed it. Why? Obviously, Arabs would come and destroy his tomb. That’s why the local rabbi insisted on burying him outside the city, here in Kiryat Arba. Temporarily. But it has been 21 years since then. At first, there was just a plaque, then it was paved. You can go and see it.”

Across the road from our conversation spot, at the end of a small alley, behind a low fence, there was indeed a tombstone with inscriptions in Hebrew. Such a place, of course, cannot be marked in any guidebook or map. It is impossible to stumble upon it by chance. And one cannot know about someone like Baruch unless they are interested in the history of the Palestinian conflict. But what an artifact it is: a monument to a terrorist!

No man’s land

The road from Kiryat Arba to Hebron goes through hilly terrain, passing through some completely unkempt huts and winding streets. The maps of this area are imprecise, and the navigator malfunctions.

But even if you manage to orient yourself and go in the right direction, it is still impossible to figure out how to enter Hebron. Look at where the map leads. Hebron is on the horizon, and the road descending sharply to the right. There are no signs or side streets — no indication whatsoever of how to proceed into the city.

But there begins to linger some nervous tension in the atmosphere. Shouts of local youth in Arabic can be heard in the distance, while children run across the rooftops, releasing homemade kites made from black polyethylene bags. They make similar ones in Indian slums. But India is a peaceful country, while this is militant Palestine.

Only the locals helped, kindly escorting us all the way to the checkpoint. Honestly, for a moment, it seemed like they were leading us to our death: after descending the road, we had to turn left, dart between the houses onto a staircase, and pass through a cave that was probably carved out many centuries ago and now overgrown with houses.

It’s simply impossible to figure out on your own that you need to go precisely here! And after Lugovsky’s stories, I felt extremely uneasy: it was right around here where his friend was approached from behind and killed by Palestinians.

Hebron clouds the mind from the first steps. On the way from Kiryat Arba, you need to cross a checkpoint with soldiers, showing them your passport and visa. This signifies a transition from the Israeli side to the Palestinian side.

The Palestinian part, which you enter after the checkpoint, is about three hundred meters wide. After passing through it and exiting the cave, you encounter another checkpoint where the accompanying Palestinian cannot pass. This means that we are once again entering Israeli territory without even spending twenty minutes in Palestine.

So far, everything is clear. But after going through the control at the entrance to Hebron, you find yourself squeezed between two fences. On the fence to the right stands the Cave of the Patriarchs — it is located in Israel. Behind the fence to the left are ruins and residential houses — they are located in Palestine.

But where located the road itself?

The descent into the city goes for several tens of meters between the fences.

And then it reaches a small square with a park. On the side stands a house with an Israeli flag.

Right next to it is a fence with a Palestinian flag. What is behind this fence — is it Palestine? And in front of it, I suppose, is Israel?

In front of the Cave of the Patriarchs stands a police station with Israeli flags.

However, if you go up and to the right from there, you come across a Palestinian wedding without encountering any barriers along the way.

But how? How is it possible if it is customary to see checkpoints with document checks at such crossings in the West Bank? If Kiryat Arba was Jewish, after the first inspection, we found ourselves in Palestinian territory, and after the second, in the Jewish part of Hebron, then where are we now? Is this Palestine or Israel?

And to whom does the road between the fences belong? It seems to be located as if between two countries. But at the same time, it appears that it belongs to neither of them!

You see, dear reader, it is very difficult to convey this feeling in words, but being in Hebron, one cannot understand where he is. It is customary for a man to have a sense of himself in a specific time and place: right now, at two in the morning, the author is sitting at home on his familiar street in a small regional city located in a country called Russia. And the reader is at home, on his own street, in his own country, which he knows precisely and unequivocally.

Hebron deprives one of this fundamental understanding: standing on the ground, knowing coordinates and even the name of the city, you cannot say where exactly you are: in Palestine or in Israel? This feeling is difficult to convey. But if you thinks about it, it begins to drive you crazy, and the reason literally cries out, “Answer me, answer me immediately! Where am I? Tell me precisely, I must know it right now: where exactly am I? Whose country is this?!”

Being on this road between two countries is like entering a looking glass, a parallel world, a black hole projecting into the inside of a closet standing in a room. It is impossible, simply impossible, to be on the road and not be in a specific country!

And there you stand, not understanding where you stand. Meanwhile, soldiers drive around the city in large military jeeps, fully equipped: wearing heavy bulletproof vests, rifles slung over their shoulders, flashlights and first aid kits in their pockets, carrying additional pistols, sporting purple berets or helmets, with backpacks, knee pads, radios, and heavy military boots.

“Gentlemen!” I dare to ask them, “I apologize, could you please tell me where we are right now? I understand that it sounds strange. But there is Israel over there, and Palestine over there. If we’re standing between them, where exactly are we standing?”

“Well, we don’t even know ourselves. It’s a military zone. A disputed territory.”

A disputed territory. That’s how it looks: indistinguishable from ordinary ones, except that it drives you crazy. Well, at least such an explanation — a disputed territory — helps calm my mind for a while.

Meanwhile, somewhere nearby, something starts to explode and hiss, as if from a machine gun burst. The soldiers exchange glances.

“Is that gunfire?”

“No, probably just fireworks. They tend to provoke like that, setting off firecrackers. It happens all the time.”

Hebron is an oppressive place. Everything reminds you that it is a real war zone.

All the windows of the houses are boarded up and barred, and many roofs have booths where snipers can monitor during periods of unrest.

Concrete blocks in the shape of the letter “P” are scattered on the streets, which are used as cover during gunfights.

To better control the city streets, passageways between houses are barricaded with a pile of concrete blocks or rusty containers — whatever is necessary — the main goal is to have as few enemy access points as possible, allowing movement only along the main streets.

Some entrances to the houses are boarded up with iron shields.

But the most significant thing is the checkpoints in the middle of the streets. Tourists pass through them without any issues, but Palestinians are subjected to personal belongings inspections each time.

Just stepping away from the central square, where the police station is located, you think twice: Is it worth continuing further?

Hebron can be the setting for a horror film. When in the middle of a war-ravaged city, with mannequins of terrorists on rooftops and shelters from shelling, a lone scruffy kid plays ball, bouncing it off concrete structures and shouting something in Arabic upon seeing white people — something inside twitches.

The road leads further into an even more real Hebron. But is it worth going there?

No, this is too much. The walls of Bethlehem could still be endured; they were peaceful, although they looked intimidating. But in Hebron, it’s simply a war zone. It’s better to leave here. And not the same way I came — I don’t want to go through those caves again. It’s possible to leave the city through the Palestinian side, but how do I get there?

Ghost Town

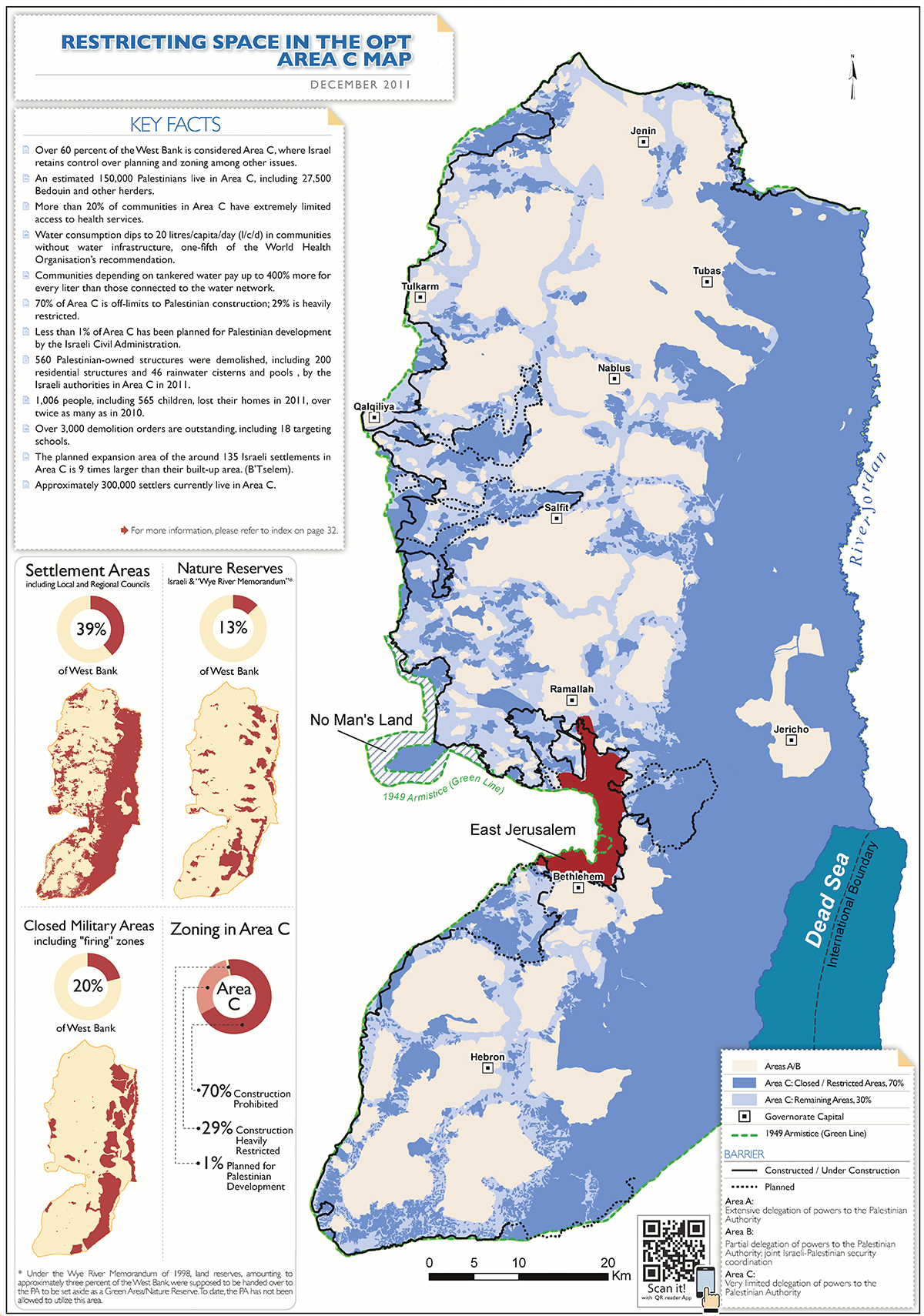

The only peaceful place in Hebron is near the police station and the Cave of the Patriarchs. The cave is already closed; it’s around five o’clock, and Shabbat is about to begin. But here, there are constantly military personnel on duty, and it’s relatively clean. On the way, you come across a couple of young people dressed in protective-colored clothing with the marking “EAPPI” — an international religious organization with a peacekeeping and observer mission in Palestine. By their appearance, these guys resemble Jehovah’s Witnesses: similar types with light hair, wearing identical clothes, and with a sweet smile on their faces that reveals some underlying belief.

“Good day. Can you tell me how to get out of here?”

“Hello. Where do you need to go?”

“To Jerusalem or Bethlehem. Just away from here.”

“Are you Jewish? From Israel?”

“No, from Russia.”

“That’s good...” What did he mean by that? “Oh, how can I explain to you? To the left of the Cave of the Patriarchs, there is a checkpoint. You need to pass through it, then turn left and pass through another one — you will find yourself on a street where there’s an old abandoned market. The street is straight, with houses on both sides — you just need to keep going straight. There will be a turn at one point, the street will start curving — ignore it, keep going straight until you exit the market into the city. And there you will find taxis, minibusses, or a bus — they will take you to Bethlehem. From there, you can catch a taxi to Jerusalem after crossing the wall.”

“Understood. Is it possible to leave through the Jewish side?”

“I wouldn’t recommend it.”

“But that’s how we ended up here. Are we crazy?”

“Oh no, not at all.”

“Is it safe at the abandoned market?”

“Yes, absolutely.”

“Are you sure?”

“Hmm, yes, it’s safe there. Don’t worry.”

Don’t worry. It’s easy for you to say in your uniform.

Indeed, behind the two checkpoints, there was an abandoned market. The street was squeezed between continuous walls of houses with boarded-up doors on both sides.

At the top, along the entire market, there is an iron mesh stretched with piles of garbage on it. They say that it’s the Jews living on the upper floors who throw trash from their windows onto the Arabs.

This street is part of the old city, currently located in the Israeli-controlled part of Hebron. It’s not entirely clear what is happening here. If the checkpoints have been passed, then why is it considered the Israeli section? How could Jews throw trash at Arabs if they are not supposed to live in the same houses at all?

The division of Hebron is simple only on paper. It seems that both peoples can actually live here simultaneously. However, they are separated from each other to the extent that only Jews can walk on the right side of a street, while Palestinians can only walk on the left side. And all under military supervision. It’s a terrible place.

The abandoned market turned out to be even more uncomfortable than among ruins. There’s nowhere to turn, you can’t even fly away because there’s a mesh overhead. There’s no one on the street, only occasionally some women in black abayas or suspicious Arabs passing by, glancing at foreigners.

I want to leave here as quickly as possible. But going back is not an option, this path is now the only one. I can only increase my pace, even run a bit, to quickly reach the city and catch a bus.

You can also meet their children here. Palestinian children who race through the abandoned city on their bicycles. They seem to sense fear and deliberately play on it: they accelerate along a straight street and come flying towards you at full speed, shouting at the top of their lungs: “A-A-A-A-A-A!”

You try to dodge, but they steer towards you! At the last moment, they sharply brake and veer off to the side. Goosebumps all over. As you start to quicken your pace, you hear a sinister laughter of children behind you. It’s like a horror movie.

Somewhere in the middle of the street, hangs an old sign that says “Tourist Center.” What the hell! Clearly, it’s a ploy to lure someone into an alley where they will be ambushed and attacked.

The market street continues for half a kilometer already, and there is still no way out. Finally, it takes the long-awaited turn where at least the sky can be seen overhead. This is halfway through the journey.

The first signs of people. Ruins of houses with Israeli flags, guard towers on the rooftops, and barbed wire.

After a short break, the street plunges back into the market. Now, instead of houses, there are empty stalls on the sides, and instead of an iron mesh on the ceiling, torn rags made from bags and cloth hang.

Finally, the abandoned market comes to an end, leading to a relatively decent street, although there are no buses or taxis there. And there are no bus stops on the map either. What now? Should we continue forward? If we’re already lost, we’ll end up in the same slums again. Should we go back? Never! Just not back to the market again!

Suddenly, from the direction of the market, a well-dressed young man emerges, wearing a white office shirt and black trousers. A Palestinian.

“Hey, hello.”

“Well, hello.” (We didn’t need you here.)

“What are you looking for?”

“A bus stop. We want to get out of here.”

“Ah, you need to go further in that direction. Or go back, you can leave through the Jewish section, there are buses there.”

“We just came from there; they told us it’s better to leave through the Palestinian side. But there don’t seem to be any buses here.”

The guy in the white shirt inspires trust and speaks good English. It seems that it’s possible to have a conversation with him.

“Listen, buddy. What’s going on here? Abandoned markets, military people, it’s like a nightmare.”

“Ha, well, this is Hebron. Don’t you know? The city was divided in half by the Jews, they occupied half of it and set up checkpoints. We can’t walk around peacefully here; our homes and schools are over there. All the markets had to be closed. Have you explored the city thoroughly? Seen everything?”

“No, just the part near the Cave of the Patriarchs. We didn’t go further; there were only ruins. We decided to leave.”

“That’s a pity! Come with me, I’ll show you everything here!”

“It’s kind of creepy, though.”

“Why? What’s there to be afraid of? Look around. There’s a checkpoint with soldiers. They’re protecting us. Further ahead, there’s the police, snipers everywhere. What’s there to fear? This is a military zone, every step is monitored. Let’s go, I’ll show you the city. By the way, I’m from a human rights organization. I’ll show you our project.”

Damn it! Let’s go. Ahead — who knows what awaits us, behind — a market with crazy children. And if we have to stay here forever, at least let’s see the city. Besides, it’s true: there are soldiers everywhere. Maybe Hebron isn’t that scary after all?

And we turn around and go back, not through the market, but slightly to the right, taking a different path guided by our random guide — it’s not entirely clear where exactly, but it’s definitely clear that it leads straight to that part of the city where we hesitated before.

Concrete barricades appear on the road again. This time with signs that say “Boycott Israel! Fight ghost town!”

Two hundred meters ahead, a serious checkpoint emerges. We pass through it without any issues, while our companion undergoes a thorough inspection: they are compelled to empty their pockets and show all their belongings.

After crossing the checkpoint, the guide, cursing at the soldiers, begins their tour.

The guide tells: “This part of the city is called ’Ghost City.’ Once, Hebron was entirely Palestinian, but in its historic area near the Cave of the Patriarchs, there used to be a few hundred Jewish residents. Then, the Jewish terrorist Baruch Goldstein opened fire on praying Muslims in the mosque, prompting Israeli authorities to close all the shops, restrict Palestinians from moving around the streets, and deploy their military personnel everywhere.”

“They call it protection. But in that part of the city, 30 thousand Palestinians used to live! And they destroyed and shut down everything here for the sake of a few hundred Jews! Look, can you see? It’s all closed and boarded up now. There used to be a market here, people used to walk around.“

The guide turns off the street and ascends an old staircase. At the top of a small hill — since the entire city is built on hills — a familiar sniper tower, similar to the one in Bethlehem, comes into view. Perhaps the local piece of the wall also runs through there.

There is an excellent view of Hebron from the height.

And now, after the guide’s narration, it becomes clear how Israelis and Palestinians can live in the same place: Hebron was a completely unique case where dividing the two nations along a clear line was simply impossible. They lived here side by side for many consecutive centuries. There were conflicts and violence between them — everything happened — but the city remained intact until the 21st century arrived with its intifadas and terrorists.

Now Hebron is divided into two parts, but it was impossible to instantly evict tens of thousands of Palestinians who were living in the newly established Israeli part of the city. It necessitated a certain level of coexistence: Arabs can live in the Jewish part, but with numerous medieval restrictions.

The Israeli part of Hebron constantly makes itself known: sometimes flags are displayed, and other times there’s a water tower with the Star of David.

The guide leads to an old Muslim cemetery. It is a beautiful and serene place, like a dream. An elderly man in Arab attire leads a group of children. He passes by, then stops.

“Where are you from? Are you from the USA?”

“No, from Russia.”

“Ahh, that’s good.”

And continues on. Wonderful place. Warm-hearted people.

Suddenly, two friends join the guide, seemingly appearing out of nowhere in the middle of the cemetery. Were they attending a burial? However, the guys turn out to be just as intellectual as the guide himself. Only one of them looks slightly intimidating: with an elongated neck, a slightly crooked nose, and bloodshot eyes. It’s evident from his appearance that he didn’t sleep well.

“Hey, hi!” The guys approached, greeted the guide, and introduced themselves with some Arabic names. “Are you tourists? Where are you from?”

“We’re from Russia.”

“Ohh! Unexpectedly”, the scary-looking one with a broken nose switches to Russian. “I studied in Minsk for 5 years! I really liked Russia. You’re a good country; America is bad. We love Russia in Palestine; it supports us. Though, Minsk is not in Russia. I didn’t know that when I was going there. It turned out to be in a neighboring country, but there’s no difference.”

The guide introduces his friends: “We work together in a kind of charitable organization. We collect money for the sick, elderly, and children. And we also have one special project nearby our office. I will definitely show it to you when we get there!”

From the cemetery, you can see the Patriarchs’ Cave — it’s on the left side of the photograph. So, it means we have already returned to where we started.

In this part of Hebron, it is best seen how much the city has been affected.

There are shattered stone blocks lying.

The road through the cemetery is littered with construction debris from demolished houses.

Ruins.

There was indeed a massacre here.

Destroyed houses.

Israeli checkpoints in the middle of the streets.

Children run around the cemetery and ask for money.

Abandoned taxis belonging to someone are parked in front of houses, covered in dust, with deflated tires.

Terrible devastation, garbage dumps.

Empty streets with children riding bicycles — there is nothing else for the local youth to do. No playgrounds here.

But there are children. Unfortunate, poor children. While they are young and do not fully understand the conditions they live in.

The guide, all this time, talks about the horrors that Palestinians face: “In the occupied part of the city, there are no proper schools, hospitals, or stores. People have to walk several kilometers to another part of Hebron for work. There is only one university in the city, and it’s not enough for everyone.”

Throughout the entire narrative, he mentions some “project” without giving any indication of what it is. Finally, we arrive at a secluded corner near a partially destroyed house. We circle around it from the back. The guide opens the door on the ground floor, leading down to a basement area, and says, “Please, come in! This is our headquarters. Follow me, I’ll show you the project.”

Of course! How can one refuse such an invitation? Come on, my dear, into the basement of this abandoned house in Hebron — we will show you the project! However, curiosity and trust in people prevail, and upon closer inspection, the room behind the door turns out to lead not to a basement but simply to a small space with a sofa, computer, and rug.

And we enter the Palestinian headquarters. The guide turns on the computer and solemnly declares, “Here it is! This is our project.”

The project turns out to be a regular online community called the “Hebron Peace Center” on a social network. The group raises funds for charity and maintains a small blog about Hebron.

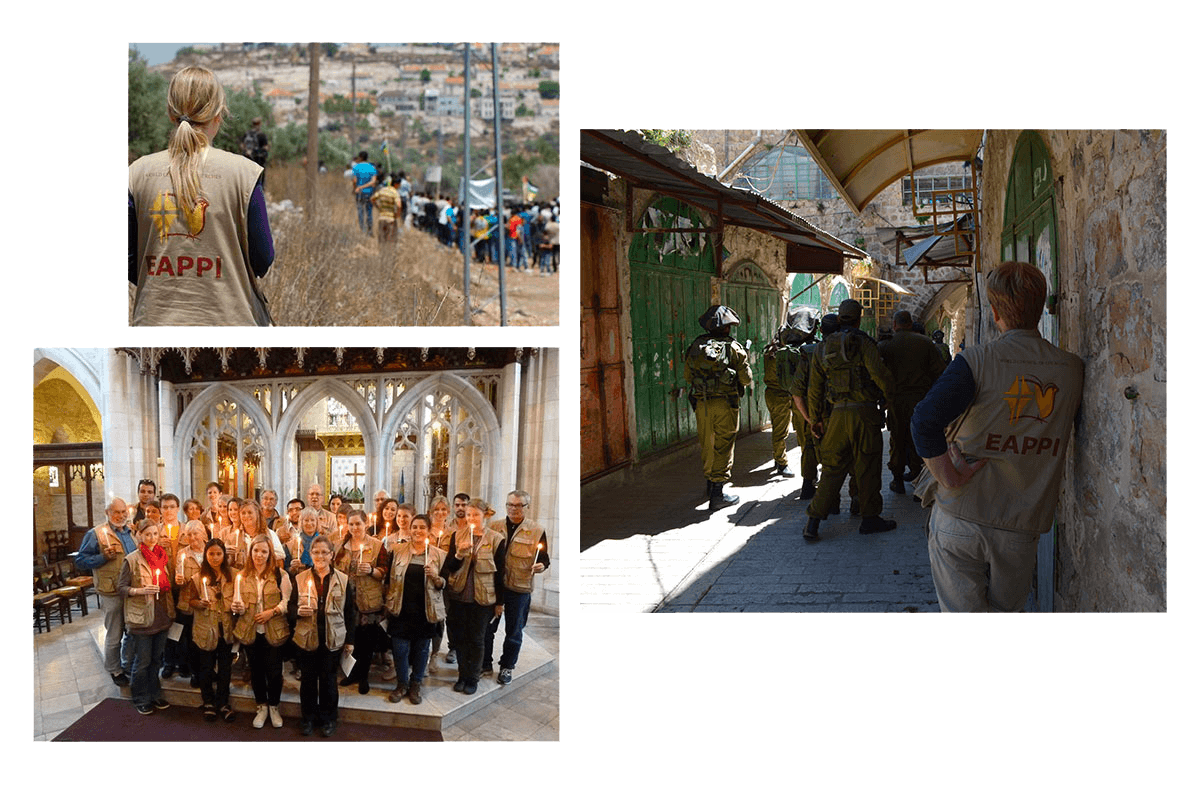

What turned out to be genuinely pleasant is that this guy, it seems, was not lying. He even showed a paper filled with childlike handwriting. It was from an English language school where he teaches.

However, the paper turned out to be filled not with exercises on verb tenses and indefinite articles but with a political agenda being pushed onto children in this English school. It read: “The occupation of Palestinian residential homes in Hebron is no longer associated with peacekeeping activities; Israel simply wants to seize the city. For instance, they renamed the Ibrahim Mosque to Ma’arat HaMachpelah...”.

In the header of the sheet, there is an incomplete star and a Palestinian flag with a heart.

What did the Kristi from Bethlehem tell? About how the rebels involve children in their games from an early age?

It’s a pity there isn’t a similar interview about the Second Intifada in Hebron. It was much bloodier than anywhere else. The city underwent such powerful destruction not because of the terrorist Baruch Goldstein — he was just a despicable moron seeking revenge for his slain friend — but because of what happened several years later. It has occurred multiple times throughout the history of these places.

And what’s the problem with renaming the Ibrahim Mosque to Ma’arat HaMachpelah? Considering that this burial site is described in the Old Testament.

Compared to Hebron, Bethlehem seems like a sea of tranquility and calm. Hebron is the collision of two nations head-on without the possibility of resolving the conflict through peaceful means or the construction of walls. The Patriarchs’ Cave, where four forefathers and their wives are buried, revered in all three religions, does not compare in religious significance to the solitary tomb of Rachel.

Bethlehem surrounded the tomb with a wall. The cave of the Patriarchs cannot be surrounded by a wall. Palestinians will not tolerate such restrictions. Similarly, Jews will not tolerate it either, as they are willing to live in Palestinian cities in small groups, in constant clashes with Muslims, but not to leave holy places.

Therefore, in Hebron, Arabs and Jews have to coexist on the same streets and go to the same mosque-synagogue. The Cave of the Patriarchs is currently divided into two parts: Muslim and Jewish, and each group prays only in their respective section, except for ten special days a year when both halls are opened.

And yet, we are in the basement of an abandoned house, together with two Palestinians, in the midst of a ruined ghost town where war, terrorist attacks, and murders have long become the norm; in a place that cannot even be clearly attributed to anyone; somewhere between a Muslim cemetery, sniper towers, the Cave of the Patriarchs, and concrete checkpoints.

Almost escaping Hebron an hour ago — how the hell could we have come back? He led us here to catch a bus in the Israeli part, and where did he bring us?

“Buddy, you have a great project. I’m glad to meet you, but we need to go. You mentioned there’s a bus station here, right?”

“Yes, it’s nearby. Or maybe we can smoke a hookah? I’ll prepare it now!”

“No, no, we don’t need any hookah. We’re running out of time.”

“Alright. Listen, we’re actually involved in charity work. If you don’t mind, could you help us with some money? Look, I’ve told you so much about the city and our lives. How much can you spare?”

“Of course! Here, take this. It’s all I can give. The rest is for my bus fare to Jerusalem,” I count out 50 shekels and give it to the guide. After all, without his tour, I wouldn’t have been able to see the city.

“Thank you,” The guide takes the money and notices my plastic card from the corner of his eye, “By the way, there’s an ATM here. Maybe you can withdraw more? It will be enough for your fare.”

“Uh... an ATM?! Here?” What is he talking about, which ATM? Half the city was destroyed by war, what ATM?

“Well, yes, it’s nearby. Shall I show you?”

“Listen, buddy, even if there is an ATM here, I can’t give any more. We need to catch the bus. How much time do we have?

It was half past seven on the clock. The sun would set in ten minutes. Staying overnight in Hebron, oh God, we absolutely didn’t want that! Quickly hoisting our backpacks, we walked briskly towards the bus station, along with the guide who couldn’t seem to detach himself from us now. What else did he want?

We passed through the Israeli checkpoint and arrived at the place where a lone guy was dribbling a ball against the wall. It wasn’t far from the police station, just a few hundred meters away. But a crowd of Palestinians had already gathered around, as if they had specifically come out of their homes for the darkness. They converged on us from different sides, about ten people in total. The guide greeted everyone, looked at the sunset sky.

“Guys, listen. It seems like the bus station is already closed. My mistake. You don’t need to go there; you need to go to the Palestinian part, where I first met you. Shall I escort you there?”

At this moment, fear started to truly overwhelm me. The bus station was closed. It was twilight outside, with no illumination in this part of the city, only ruins and a cemetery. There was a crowd of Palestinians around. Why had they surrounded us? Why wouldn’t they let us pass? What would they do next? Attack us? Politely ask to hand over the camera?

But the crowd didn’t attack or take our belongings; they just bombarded us with endless questions: Who are you? Where are you from? Why did you come here? How much is the camera worth? Children ran up, surrounding us, grabbing at our clothes and asking for money. The guide was not lagging behind either. Now, completely forgetting about the bus station and ATM, he came up with a new excuse to keep us in Hebron.

“Guys, I’ve been thinking, it was wrong of me to take money from you. How will you get home at night? Let’s go to my headquarters, I’ll return everything. Let’s go!”

With the onset of night, Hebron transformed from an extremely uncomfortable city into a real horror that one could only run away from. Run wherever our eyes could see! And we ran. The crowd and children surrounding us parted, staying behind. Nobody tightened the chain; they simply let us go. But before we could run a few meters, a cry came from behind:

“E-e-e-e-hey, s-t-o-o-o-o-o-p!”

A quick glance back made us stop: a crowd of Palestinians had already been surrounded by several armed Israeli soldiers and were being led somewhere towards a checkpoint. Someone from the crowd, whether Palestinian or soldier, waved their hand invitingly in our direction.

“The end of the walk,” an desperate thought raced through my mind. We had to obediently turn back and walk together with the soldiers towards the checkpoint. What would they do to us now? Interrogate us, surely. Why did we take photographs? Why did we enter the headquarters and what were we doing there? Why did we give money? But it seemed that the soldiers were only concerned about the Palestinians.

The guide started being searched. He passed through the checkpoint without presenting a pass and without emptying his pockets. Now he stood with his hands raised while the soldiers inspected his personal belongings.

“Look, look how they’re humiliating us!” shouted the guide. “You have a camera, take a photo of this crime!”

It became clear that the soldiers had no interest in the photos of the two lost tourists. Surprisingly, photography was not a major concern in Israel. Military zones, walls, snipers — so what? The Israeli army pretended to have no secrets from anyone. Even if they searched Palestinians simply for walking on the street without a permit, they didn’t hide it and claimed it was necessary for general security.

“Keep filming, keep filming how they’re humiliating us!” shouted the guide. But I had had enough. “Sorry, buddy. I’d rather tell it verbally,” with this thought in mind and realizing once again that the soldiers didn’t care about us at all, we ran back to the Cave of the Patriarchs, until something else happened.

No way out

Next to the Cave of the Patriarchs, at the police station, it was bright and calm. Right in front of the police station, there was a neatly landscaped lawn — an unusual, singular green space in Hebron. During the day, a few Jews would relax on the lawn. But now, as night fell, the entire area was occupied by tents, and the road next to it was filled with cars, where Jews rummaged for mattresses, candles, chairs, and warm clothing.

They came here for Shabbat.

God, what a cursed place! The city is destroyed, surrounded by cemeteries and ruins, and if you turn the corner, you’ll end up among Palestinians with who-knows-what on their minds. As if that wasn’t enough, orthodox Jews have the audacity to organize a picnic in front of the Cave of the Patriarchs every night from Friday to Saturday! They’ve arranged a green lawn in the middle of a military zone next to the security checkpoint and come here for Shabbat to spend their sacred day closer to the tombs of biblical patriarchs... Madness! A sect!

There was no time to contemplate this masquerade — we wanted to get out of Hebron at any cost. Climbing up the deserted road squeezed between two borders, we reached the checkpoint at the entrance to the city, hoping to still find a way to reach the Israeli side. Perhaps there were still buses available? Or maybe someone would give us a lift.

“Stop. Where are you heading?” Two armed soldiers stood at the checkpoint.

“To Kiryat Arba,” we replied.

“You can’t.”

“Why not? We need to go to Jerusalem.”

“Where are you from?”

“From Russia.”

“Well, hello there,” the soldier switched to pure Russian, “I’m from there myself.”

“Oh, what a meeting!” It was impossible not to be delighted by such an encounter. An Israeli soldier from Russia! Finally, someone we could trust, someone who would understand and help. “Maybe you can explain to us how to leave from here? We’re tired of this Hebron, damn it!”

“You won’t be able to leave from here. Hebron is closed. It’s Shabbat for the Jews. Entry and exit are prohibited for everyone except Jews until the end of Shabbat.”

To fall through the ground. No, what does it mean? The city is closed on the Sabbath?! But that’s until the next sunset, until Saturday!

“Are you serious? Are we supposed to stay here overnight? But we have a hotel, a plane... Let us go!”

“I can’t, I’ve been ordered not to let anyone out. You can spend the night here. There’s a campground down below with the Jews. Ask them, maybe they can help. Or ask at headquarters — we’ll find you a bed, you’ll spend the night.”

Your mother!

They say that Jews can still leave the city during Shabbat. But the sun has already set, the candles are lit. On Shabbat, not a single Jew, especially an Orthodox one, who came to rest in Hebron, would allow themselves to drive a car because of two tourists who got stuck near the Cave of the Patriarchs due to their ignorance. They should have asked about this service, but they shouldn’t have hoped for it: no one offered help. Shabbat. Not allowed.

“I’m sorry, but could you help us get out of here?” The question, addressed from below to the chief of staff standing on the second floor of the police station, seemed filled with despair, as if directed upwards to God.

“Where are you from?” For the first time, I regretted not being from Israel.

“From Russia.”

“Ah! Fellow countrymen,” the chief of staff switched to Russian. The native language didn’t offer much help in getting out of the city, but it was still a relief: to know that there were people nearby who thought and looked at things the same way you did. Apparently, Hebron is patrolled by peacekeepers from different countries for greater objectivity, so there’s no need to be surprised. “Listen, guys. You won’t be able to leave from here anymore; the city is closed for Shabbat.”

“But we can’t stay here. We have neither food nor a tent. Our flight is tomorrow evening, and our belongings are in Tel Aviv hotel.”

“Well, you’ve really gotten into a mess. I don’t know. Go into town; they have hostels there. Spend the night, and in the morning, we’ll figure something out. Maybe we’ll take you out as part of a military group.”

Hostels. Hostels in Hebron! He’s either joking or delusional. Two hours of wandering around the city — nothing but ruins. What kind of hostels are there? A den under a tombstone?

“Wait a minute, you’re from Russia, aren’t you? You have Russian passports, not Israeli ones?”

“Yes, Russian passports.”

“Then why the hell do you fuck my brain? Go to the Palestinian side, catch a taxi, and get out.”

“But we went there, there’s nothing there!”

“That can’t be, you must have gone the wrong way. See that checkpoint on the left of the Machpelah? You go through it, then walk through the abandoned market...”

Escape

They say that to conquer fear, you need to face it head-on. Walking through the abandoned Hebron market during the day was a nerve-wracking journey. Walking through it again at night seemed like a waking nightmare.

But there was no other way. After passing through two checkpoints near the Cave of the Patriarchs, we had to once again immerse ourselves in the corridor of an empty, long street, drowning in almost complete darkness. The sky at sunset still remained bright in the city, but no light reached the abandoned market, sandwiched between walls of houses and covered from above with thick patchwork blankets.

The children were still there. Now they weren’t riding their bicycles anymore, but hiding around corners and popping out just as we ran past — screaming wildly, chasing after us. But now, it was only partially scary; fear was overridden by adrenaline and the engulfing rush, an incredible cynicism towards ourselves.

And now, you no longer recoil from these children, but you counterattack with a shout in response:

“Well, come o-o-o-on! Ha-ha-ha! Damn Palestine!”

At the end of the market, there was the last taxi, with no one around. It was as if everyone deliberately dispersed and made way for it as a reward for the entire adventure. And this taxi would take us to Bethlehem for exactly the amount of money left in our pockets.

But here’s the thing. Sitting in a taxi, catching your breath from running through the scary market, and not having time to recover – after five minutes you look around. There is no trace of the old town, ruins, or war. The lights of branded electronics stores, chain cafes are glowing around, a wide illuminated highway leads into the distance, there are many people, nightlife! But where is Hebron?

And this is Hebron. Welcome to H1. It’s a regular city with modern shops, ATMs, hostels, hotels, restaurants, major companies, cafes, schools, kindergartens, residential buildings, and a university!

All of this was here, nearby, you just had to go a little further. Gradually, the ruins and devastation would have dissipated, the streets would have been filled with cars and people, and an ordinary Arab city would have begun.

But who could have known?

⁂

Having reached Bethlehem, it was necessary to overcome a considerable distance along the seven-meter Israeli wall, take another look at Banksy’s artworks, pass by Rachel’s Tomb and Anastas House, go through the winding corridor of the checkpoint between Palestine and Israel. And then spend a long time hitchhiking to Jerusalem, and after that — to Tel Aviv, rummaging through pockets to find a few leftover shekels.

But all of this was pleasant hassle. And Hebron remained in memory for a long time as the scariest city ever seen by the author during their modest traveler’s career. It drove one crazy with its uncertainty. Dispelling horror in the atmosphere of ruined streets and a ghost town. Lurking and luring with the intention of striking from behind — but never actually delivering the blow.

The scariest city on Earth — Hebron. Can’t wait to return there.