Jerusalem

Arriving in the most sacred city on Earth — Jerusalem — you expect to see only historical antiquity, the ruins of the old temple, crowds of pilgrims, and the centuries-old way of life frozen in time...

...but the first thing you see when entering the city from the bus station side is the ultra-modern Jerusalem tram.

This is a Citadis tram; vehicles from the same family are supplied to Dubai, Melbourne, Barcelona, and Paris by the French company Alstom. It is one of the most modern trams, a beauty. In Jerusalem, the tram consists of two cars. It is so long that it doesn’t fit in the frame.

The tram doors open precisely at the level of the platform: no problems for people with disabilities and passengers with strollers.

The tram travels through the entire city, passing by the historical center. Next to the Old City, the tracks are laid across a green lawn.

In the rest of Jerusalem, the tram tracks are laid in such a way that there are no curbs at all. The sidewalk and tracks are at the same level, with identical tiles. People walk as if there is no tram at all.

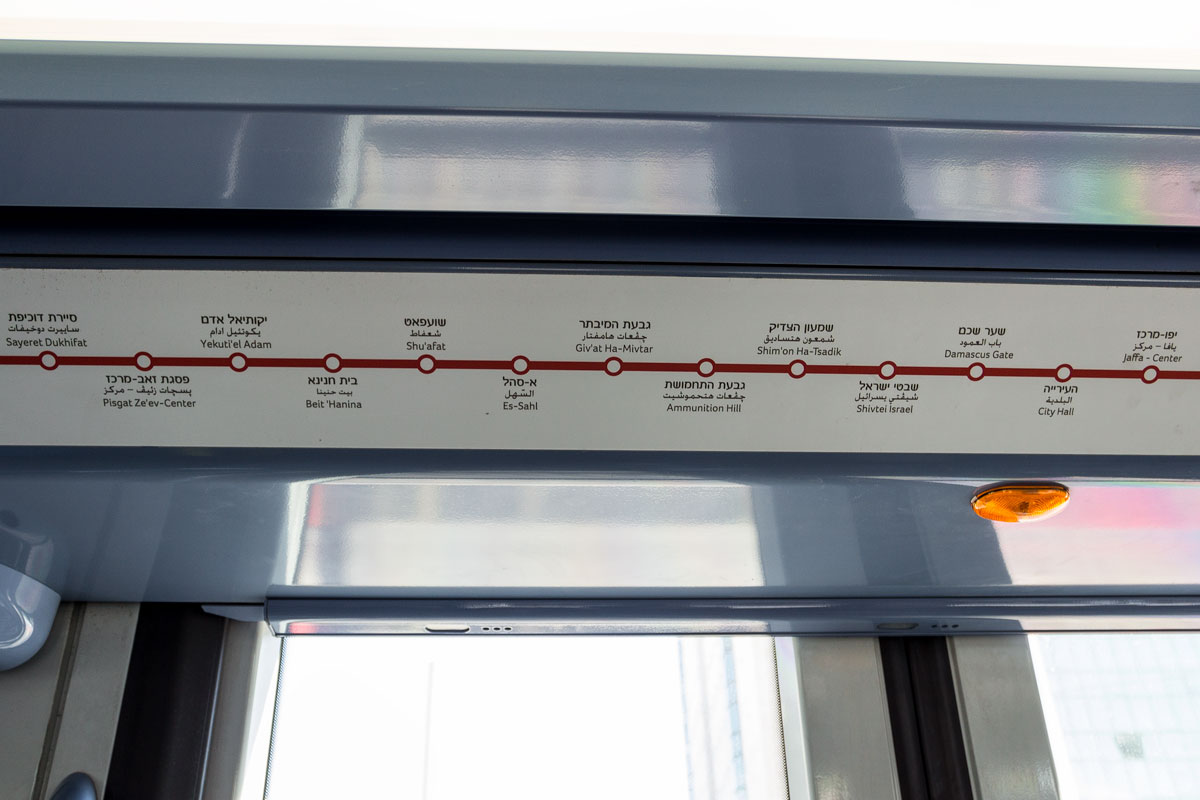

Bus stop and route map.

Tram interior. The width of the salon is standard, two and a half meters, but the space is used more efficiently. The tram is equipped with electronic validators of some antiquated variety and a paper map of stops in three languages.

Jerusalem itself turned out to be a rather modern city, resembling a Central European one.

It is immediately evident that it is a highly touristy place. Cleanliness everywhere is impeccable, and there are many summer cafes.

The city is very well organized. There are bike rentals, benches everywhere, and trash bins.

Of course, they haven’t forgotten about the trees.

In spring, everything blooms just like in Tel Aviv. It’s beautiful.

The alleyways are cozy.

It is customary to abundantly decorate homes with flowers.

Entrance to some charitable organization, perhaps a church.

Street signs.

Mailboxes.

Lovely.

Coziness.

Beauty.

Jerusalem is kept in astonishing cleanliness.

Apparently, due to the cleanliness and urban improvement, the city looks quite bland. All the buildings here are actually modern constructions. They took old square huts, adorned them with stylized textures resembling stone, making them look like antiquity.

But you can’t hide the simplicity of the architecture. It is evident that the houses are just ordinary residential cubes.

Only occasionally something Eastern is encountered. In reality, these textured cobblestones are called Jerusalem stone. Similar ones were used in the construction of Jerusalem two thousand years ago.

Indeed, it is done with great quality. However, if you strip off these stones from the facades, what remains are typical Arab shops combined with housing.

At the construction site, you can see what a house looks like without cladding. It’s just a plain gray concrete block.

Graffiti. There is a lot of it throughout Israel. Tel Aviv is covered in graffiti, and in Palestine, there’s Banksy on every wall. It’s surprising that nobody here gets upset about it, like saying they’ve defiled historical sites.

On the contrary, modern culture is welcomed here. For instance, right in the center, there are bicycles. As you pedal, a fan operates or music plays.

Archimedes’ screw.

Stone cushions.

Very cool lanterns located a hundred meters from the ancient walls.

And here are the ancient walls themselves.

Of course, the entire Old City has long been touristy. The first thing you see is a children’s train heading towards the Western Wall.

In general, the Old City doesn’t differ much from the rest of Jerusalem. Currency exchange, shops, cafes can be found there as well.

In some places, you can even go by car.

It would be understandable if you couldn’t, as people live here after all.

Of course, everything is very clean. The ancient slopes are equipped with stairs and ramps for wheelchairs.

Hydrants, pipelines, electrical panels. Thankfully, there are no air conditioners.

Traces of ancient arches can be seen in the new walls.

In the yards — beauty.

The old city is divided into four quarters: Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Armenian. The most populous is the Muslim quarter, with 30,000 residents. The Jewish quarter has only 5,000 residents.

There is no visual difference between the quarters. The buildings everywhere look the same, and you don’t notice any transition between sectors. Somewhere in the center of all this is one long market, mostly frequented by Arabs.

The market is like any other market. It’s exactly the same as everywhere else.

They sell all sorts of junk mixed together: clothes, spices, sweets, electronics, shoes. It’s completely unclear why this peddler’s den is located near the Temple Mount. Similar market stalls in Moscow near the metro stations get dispersed in droves.

Even a navigator hardly works in these alleys. There are walls around, canopies above. You step out randomly.

It turns out, I arrived at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Here is an interesting detail — a staircase by one of the windows on the second floor. It’s called the Immovable Ladder. The cornice it rests upon belongs to the Orthodox Church, while the window belongs to the Armenian Church.

Of course, it’s Jerusalem. Here, there has been and continues to be an endless struggle for the holy sites. At one point, six Christian churches disputed the right to control the tomb of their Lord, Jesus Christ. They argued according to their respective traditions: monks would punch each other, priests would vandalize the interior of the church. In general, as is usual in any religion, with stabbings and riots.

As a result, the Ottoman authorities, who ruled over Israel at the time, introduced a series of strict laws and imposed a high fee for entry into the church. It is said that the Armenians supposedly placed this ladder to climb into the church through the cornice without paying the entrance fee. When all the Christian churches finally reached an agreement on the rights of ownership of the church, they decided to keep the ladder as a symbol of the strict observance of the achieved status quo.

Now it serves as a symbol of peace, and the ladder cannot be moved, while different parts of the church are divided among the denominations.

Inside the church is somewhat like this. It’s dark and crowded with people. Light seeps through a small window in the dome.

The line to the tomb. It is located in a small chapel inside the church. It doesn’t hold anything interesting, just a stone box with a slab. Naturally, there is nothing inside the tomb. It is actually called “Empty Tomb” in English. Originally, it was more like a bed rather than a tomb. The slab was placed on top later.

In addition to the tomb, by a remarkable coincidence, the church also houses Golgotha, the Stone of Anointing, the prison of Jesus, a crack in the rock, and the navel of the earth.

Let’s proceed to the Jewish quarter. It is the smallest of them all and the quietest.

Here it is surprisingly clean, almost embarrassingly so. No stalls or markets at all.

Well, they sell some souvenirs in a couple of places here.

Somewhere among the narrow alleyways, where it’s easy to get lost, is the entrance to the most famous landmark of Jerusalem — the Western Wall.

You pass through the metal detector frame and arrive at a staircase that leads to a large square.

Actually, that wall in the distance is the Western Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall. It is overgrown and nothing stands out about it.

Nothing except for its history. It is the only remaining part of the magnificent Jerusalem Temple that stood on this site almost three thousand years ago, the center of Judaism, just as holy to the Jews as the Vatican is to Catholics. The Temple was destroyed and rebuilt twice until it was ultimately destroyed by the Roman Empire. The wall fragment is the only thing that remains.

Nowadays, thousands of Jews come to the Wall every day to mourn the Temple. The name “Wailing Wall” was actually given by Arabs who witnessed these Jewish lamentations. In English and Hebrew, it is called the “Western Wall.”

Rituals are complex and not easily understood by those unfamiliar with Judaism. Jews approach the wall, stand close to it facing it directly, sway back and forth, whisper something, and place notes with prayers.

By the way, the wall is actually several times taller; it simply extends deep underground.

But what happened to the temple? Where are its ruins, what stands in its place? Now a Muslim mosque is located here. That’s its gray dome.

Next to it, there is another golden one — it’s also part of the mosque complex. It is undoubtedly recognized as a symbol of Jerusalem. Let’s find a better photograph and take a look at the Old City from above to get a closer look at everything.

This entire place, surrounded by high walls, is called the Temple Mount. The small gray dome nearby to the south is the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The large golden dome is called the Dome of the Rock and was built around the so-called Foundation Stone, a Jewish holy site, from which, according to legend, God began the creation of the world.

And where is the Western Wall? The Jewish holy site is so small that it becomes a focal point in this vast city. To save the reader from having to search throughout the entire photograph, I have marked it on the picture.

Isn’t it true that this state of affairs sheds light on the relationship between Jews and Muslims? From the revered Jewish temple, only a pitiful piece of wall remains, and this inevitably led to a sorrowful conflict.

What do the conflicting parties say about the Temple Mount? The two most extreme opinions are as follows:

The issue of Jerusalem is extremely complex. During a war, the city was separated from Palestine, annexed, and established as the capital of Israel. Such status is still not recognized by half of the world. Jerusalem balances on a delicate edge. Any event can become the catalyst for a surge in terrorism, as it once served as a pretext for the armed uprising of Palestinians when the Israeli president visited the Temple Mount.

Well, the city lives its contradictory life. Muslims go to pray.

Jews mourn the ruins of the ancient temple.

Elite graves are sold on the Mount of Olives.

Streams of Arab homes vanish somewhere beyond the horizon. And we follow them to Palestine.