Agra. The Taj Mahal and Edwin’s family

Rail transportation in India is something. In terms of railway length, India is second only to Russia, but the quality is stuck somewhere in the mid-20th century.

For example, the Indian sleeper class is not just two, but three berths in a row. The third berth, in the middle, is formed by lifting the backrest of the seat to a horizontal position. Of course, when it is lifted, sitting becomes uncomfortable as the head will rest against it.

Such a three-tier sleeper is called a “sleeper.” There are several variations of it: with or without air conditioning, with two levels instead of three. The sleeper class is not the worst option for travel. Much worse are the sitting seats. Some of them are reserved when purchasing a ticket, while others fall into the category of “unreserved.” As many people as can fit will board and travel in the unreserved section.

Unreserved tickets are extremely cheap, so they are popular among the poor population. The sitting coach looks like a regular Russian commuter train with soft or wooden seats in two rows. The only difference is that during rush hours on popular routes, the coach is packed to the point where there is no space to move or breathe. It’s quite an experience. Traveling in such a manner makes no sense, but for the sake of sensations, it’s worth simply visiting Bombay and taking a ride on the suburban trains there.

There are numerous trains that run from Delhi to the city of Agra. The duration of the journey ranges from two to six hours or more, depending on the route (which is unpredictable here), transfers, delays, and the novelty of the train.

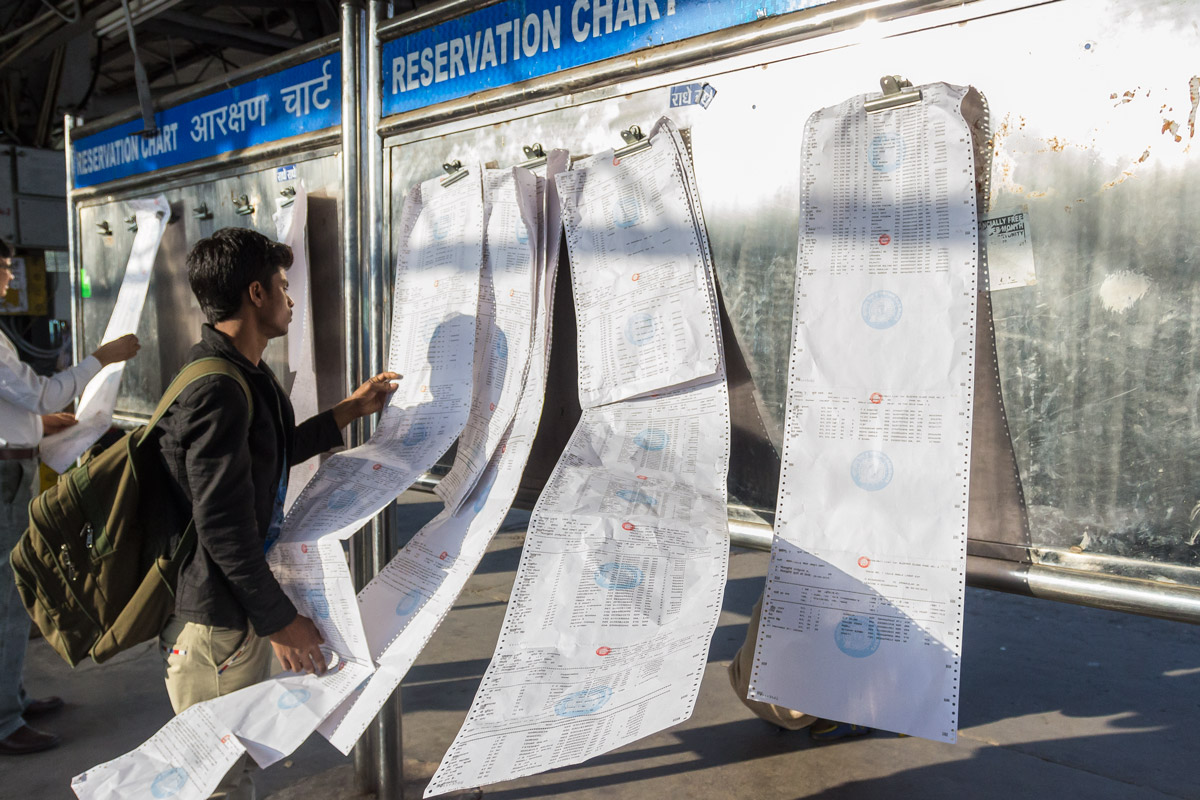

Giant lists of passengers’ surnames are displayed at the train station. One needs to come to the station and find their name on these lists to determine the coach and seat. The lists are attached with office clips, so they constantly fly away in the wind. Passengers chase after them all over the platform.

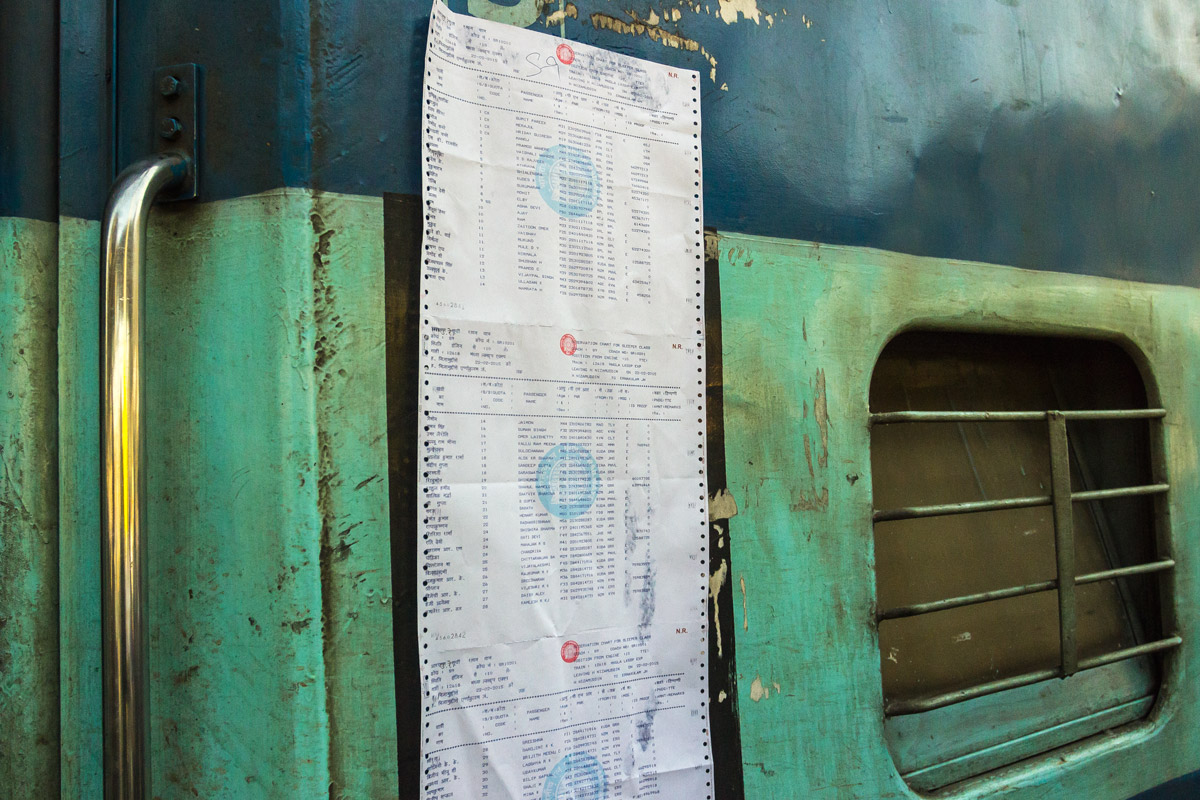

At the entrance of the coach, the list is duplicated specifically for that particular coach.

Welcome to the Indian sleeper class.

Side seat by the window. You can see that the backrest is attached with hinges. The backrests can be lifted from both sides, like the bridges in St. Petersburg, creating a middle berth. Three switches control the air conditioner.

Well, about the air conditioner... Fans are hanging all over the ceiling. It’s inexpensive and provides some relief from the heat.

In principle, it’s not much worse than old Russian trains. It’s a bit dirtier and resembles a prison due to the dull lighting, window grilles, and green-gray color.

It’s safe to travel. Indians are completely harmless, and travelers from Russia are always welcome.

Food vendors constantly walk through the coach, repeatedly saying, “chai, kofe, kofe, chai.” At some point, the Indian sitting next to me can’t take it anymore and shouts, “Hey, chai!” It’s a dialogue that is understood without translation. In response, they pour some rusty water into a plastic cup for him. It looks least like tea. I don’t think it’s worth drinking.

The level of poverty in trains is simply extreme. For example, someone can easily be lying down in the compartment, and it doesn’t matter: they’ll bypass somehow.

Blatant self-flagellation happens as well.

For example, someone crawling on their knees and elbows, scooping up all the dirt from the floor, dressed in tattered rags. In his hands he holds a rag soaked with dirt down to every thread; it’s so filthy that it seems to be made not of fabric, but of pure dirt itself.

And here he is, crawling almost on his belly along the floor, wiping the rag in front of him and under the feet of those sitting. It feels like he might just start eating the scattered garbage and licking the floor with his tongue any moment. It’s an incredible level of self-degradation. Usually, he receives nothing when reaching out his hand since no one even wants to look at him.

I felt ashamed to film him, but another time I discreetly started recording. A less frightening character crawled through the coach — a legless cripple with a lost, insane gaze.

The platforms along the way to Agra are no different from Russian ones, just lower. Passengers jump off them and cross the tracks.

Landscapes. I thought India looked more deserted and brown. It turns out it’s quite green here, and they even grow things.

Agra.

Agra is a small city located two hundred kilometers from Delhi. The city’s name is not well-known to many, but everyone knows about the Taj Mahal, which is located here. The city fort is slightly less famous. The city itself is of absolutely no interest, like some isolated community.

Cows feed from garbage bins.

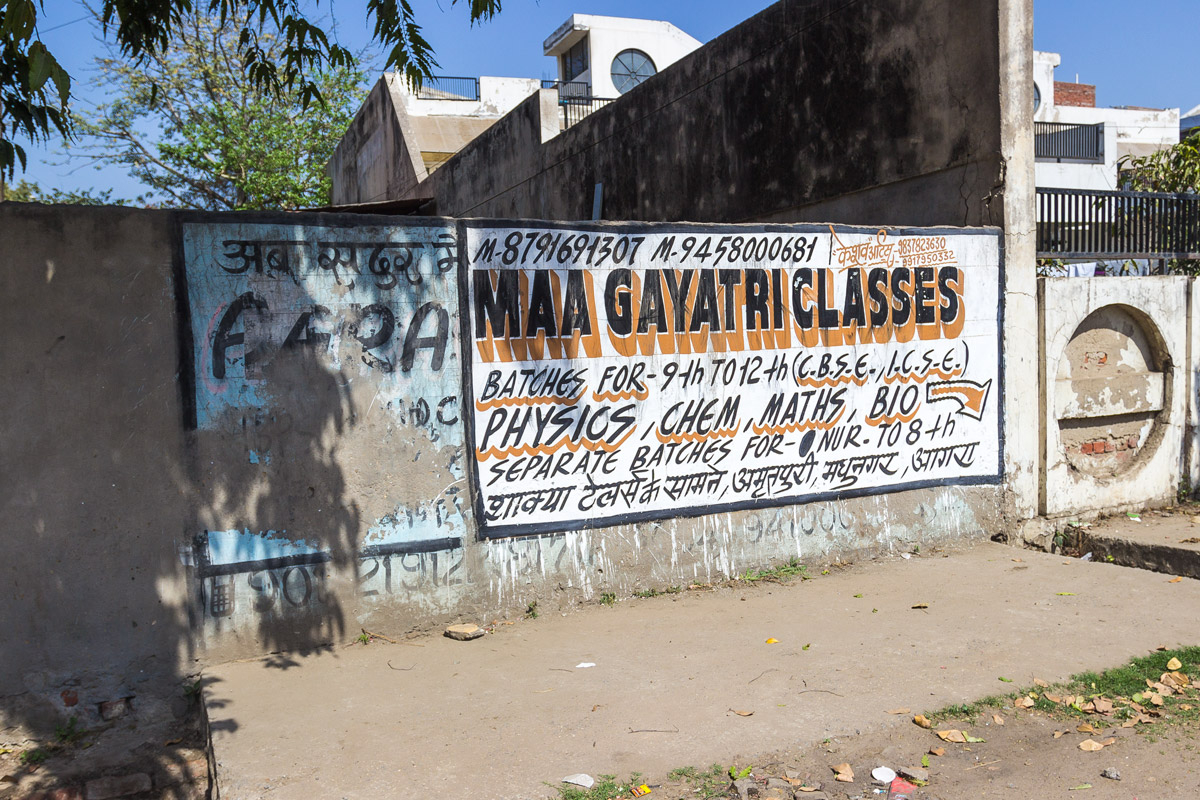

Advertisement for physics and mathematics courses.

Agrin Red Fort. It doesn’t differ from the Red Fort in Delhi. There are plenty of these red forts in India.

The dried-up river near the fort is littered with garbage.

Inside, of course, it’s clean. But it’s also empty. There’s absolutely nothing worth seeing.

Oh, look, little parrots!

Nyaaa.

But from the fort, you can see the Taj Mahal. It is located on the riverbank. According to legend, a black Taj Mahal was supposed to be built on the opposite side of the river.

Closer.

The distance from the fort to the Taj Mahal is not far. You can take a local minibus to get there.

You can also walk and, for example, come across a monument to a horse with equine glanders.

The Taj Mahal is situated in a large garden, with entrance accessible from three sides (excluding the river side) through big red brick gates. Adjacent to the gates and walls are similar shabby huts, like in all of Delhi. The surrounding area is completely neglected.

The same tuk-tuks and vendors selling everything imaginable. Agra doesn’t differ from any other Indian city.

I really didn’t want to pay 750 rupees for the entrance to the Taj Mahal, so I started looking for a way to capture it from the rooftops of nearby houses. I explored everything I could. This is the best view you can get this way. You can’t really see anything properly.

Had to go to the ticket counter. After purchasing the ticket, I was approached by an Indian who introduced himself as a guide and started persuading me to take a tour for an additional 750 rupees. I ignored him for a long time, but he followed me through the entire queue, eventually lowering the price to 200 rupees.

In the end, I fell for the offer to capture the Taj Mahal at night. I still can’t tell if it was my imagination or if he deceived me by saying he would take me there with a tripod after closing time. But in the end, I agreed. It turned out to be worth it.

The Taj Mahal is impressive.

Not many people know that it is a Muslim mosque. Prayers are held here on Fridays. The perimeter of the entrance arch is adorned with Persian calligraphy. The guide assured me that the letters at the top are made larger than those at the bottom, but from a distance, they appear identical. No differences could be found.

But the color truly changes with the sunlight. The patterns also shimmer.

The ornament is inlaid with four types of stones. They were brought from different countries. Malachite comes from Russia.

Optical illusion.

In reality, these columns are perfectly straight.

It’s boring inside. The Taj Mahal is actually a mausoleum where the Shah and his wife are buried. There are two tombs inside. During the day, light enters through a small window, but it becomes completely dark by sunset. Photography is not allowed, but everyone takes pictures with their flash anyway, even though there’s nothing worth photographing.

During the course of the tour, it became apparent that not only was it impossible to enter the premises after closing time, but also pointless: there is no illumination at the Taj Mahal, and it remains in complete darkness.

The guide turned out to be a rather interesting character. His name was Edwin, and he studied Russian language at Agra University. According to his account, he was even a successful student, and during the time of perestroika, he was offered an opportunity to study in the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, his parents did not allow him to go.

I must have impressed Edwin somehow, and he invited me to his house for dinner. I was taken aback.

“Are you inviting me to your house?”

“Of course! You’ll be my guest.”

“But I have a train to Delhi, and there’s only an hour and a half left.”

“Don’t worry, I live 10 minutes away from the station. You’ll make it.”

We arrived at Edwin’s when there was only an hour left before the train departure. The house turned out to be a typical, untidy brick building, much like many of the dwellings that make up most Indian cities. The house had two low floors and a small courtyard with a typical rural toilet, a cold-water sink, and a parking spot for a motorcycle.

One had to climb the stairs to reach the second floor. It seemed that there were two living rooms on the second floor. In one of the rooms, there was a small kitchenette separated from the workspace and bed by a modest yellow curtain. There was also an unfinished open area where some barrels stood, various items were scattered around, similar to what can often be found on any balcony, and laundry was drying on ropes.

The prayer room was located on the ground floor. Surprisingly, Edwin turned out to be a pastor of a Catholic church called God’s Believers Army. The entrance to the room was through an opening in the wall with an untidy arch above it and a curtain instead of a door.

Leaving me to interact with his daughters, Edwin rushed to the store to look for chicken. Prior to this, on the way home, he had already stopped by several shops but couldn’t find anything. Perhaps meat is not consumed very often in Agra, so it felt like they were specifically searching for chicken for the honored guest.

There are six people in Edwin’s family: his wife, two daughters, brother, and son. The eldest daughter speaks Russian very well, and other family members are not far behind.

There was an old computer in the house, but the power cable turned out to be broken. There was also internet in the house, but a dedicated line was expensive, so everyone used mobile internet. Someone used an old Symbian phone, while others had inexpensive Android devices. In any case, everyone was registered on Facebook and communicated through WhatsApp.

As far as I understood, the entire family is educated. Edwin graduated from Agra University, and his children are currently studying: some are completing their secondary education, while others are pursuing higher education. There were several textbooks on chemistry, physics, mathematics, and biology lying around the house. In one of the photographs, there is a thick solutions manual for ICSE (Indian Certificate of Secondary Education) problem sets spanning 10 years.

While I was examining the dwelling with undisguised curiosity and amazement, after about half an hour of absence, Edwin finally returned with the chicken, and his wife started preparing dinner. By the time dinner was ready, there were only twenty minutes left before my train departure, so I had to eat hastily.

Several large plates were placed on the table. One plate was filled to the brim with boiled rice, while another held Indian flatbreads called chapatis. In the third plate, there were some legumes, it seemed. The chicken was served in a small pot with curry sauce.

Here, I must honestly admit that I was somewhat apprehensive about eating chicken meat due to reading about the possibility of contracting intestinal infections or, worse, typhoid fever. I was unaware of the feeding practices for chickens in India, as well as how they are plucked, eviscerated, and stored. It was also unknown what utensils they were cooked with. What is the quality of the tap water?

But I couldn’t refuse the dinner that was specially prepared for me. I planned to eat as little as possible, but Edwin, like a caring grandmother, kept adding piece after piece, saying, “Eat, it’s all for you.” I had to eat the whole chicken. After that dinner, my stomach felt a bit uneasy, but probably because I hadn’t eaten anything all day. By the next morning, the heartburn subsided, and there were no further consequences.

Meanwhile, there were only ten minutes left before the train departure. Edwin quickly helped me throw my things into the backpack and swiftly left the house. I had already given up hope, but then he rolled out a motorcycle and shouted, “Jump on quickly!” I jumped onto the luggage rack and held onto the sides—I had never ridden anything other than a car before.

It won’t start!

The motorcycle refused to start. And time was ticking. Tomorrow morning, I have a flight to Varanasi that I absolutely cannot be late for. Edwin shouts, “Get off!” After several attempts, the engine started, and I hopped onto the back seat. In an instant, Edwin took off, swiftly flew out of the gates, and raced me through the night in Agra at such speed and recklessness that it couldn’t be compared even to crazy rickshaws. It’s a pity I couldn’t capture this part of the journey. If only I had thought to move and grab the camera from my backpack or the phone from my pocket, I would have been instantly thrown off the motorcycle. Edwin swerved between cars and tuk-tuks like a madman, trying to make it to the station on time.

Upon reaching the station, Edwin literally threw the motorcycle onto the asphalt and ran to the platform. We were out of breath from climbing the stairs. We approached the platform, listening to the announcement in Hindi. We looked at the departure board. It had left 1 minute ago.

“Well, there will be another one,” he says, “or you can stay overnight at my place.”

“You know,” I say, “I don’t believe it. It didn’t leave. They always run late here. I’ve looked at the statistics for this route. On average, by half an hour. It has never arrived on time.”

“It left, it left. This is a new train. It doesn’t run late.”

They started walking along the platform, talking about life. Edwin shared his story about how he had tried to go to the USSR and how his parents took away and burned his passport: “You’ll leave, find yourself a wife there, and stay there forever.” They also discussed faith and people. Then he remembered that he had left the motorcycle unattended at night and became agitated.

At that moment, they announced a train delay. It hadn’t departed; it was just running late, as the statistics had predicted, exactly by half an hour. It turned out to be a truly new and modern train.

And I sat in my seat by the window, facing the platform side, and we departed. Edwin stood for a few minutes, waiting for the train to leave, and when it started moving, he continued walking for a while, picking up his pace, clasping his hands together, and muttering something to himself.