Varanasi.

Part One. Sunrise

There is a city of medium size in India, the name of which is seldom heard, but pictures from where have been seen by many. This city is called Varanasi and it is famous for its vibrant religious life. It is here that mass bathing rituals take place in the Ganges River, and pilgrims from all over the world gather here, including Buddhists and Hindus. Additionally, Varanasi hosts ritual funerals associated with the cremation of human bodies in open air and the subsequent scattering of ashes in the Ganges.

The significance of Varanasi for Hindus is as infinite as the significance of the Vatican for Catholics. Varanasi is considered the holiest place on the planet, and Hindu cosmology regards this city as the absolute center of the Earth. It is the oldest city in India and one of the oldest cities in the world. According to legend, the city was founded by the god Shiva five thousand years ago. From a scientific perspective, Varanasi has been continuously inhabited for at least three thousand years.

But behind the beautiful history and traditions, there is another side to Varanasi. It is the most cynical, corrupt, hypocritical, dirty, and intimidating city in India.

⁂

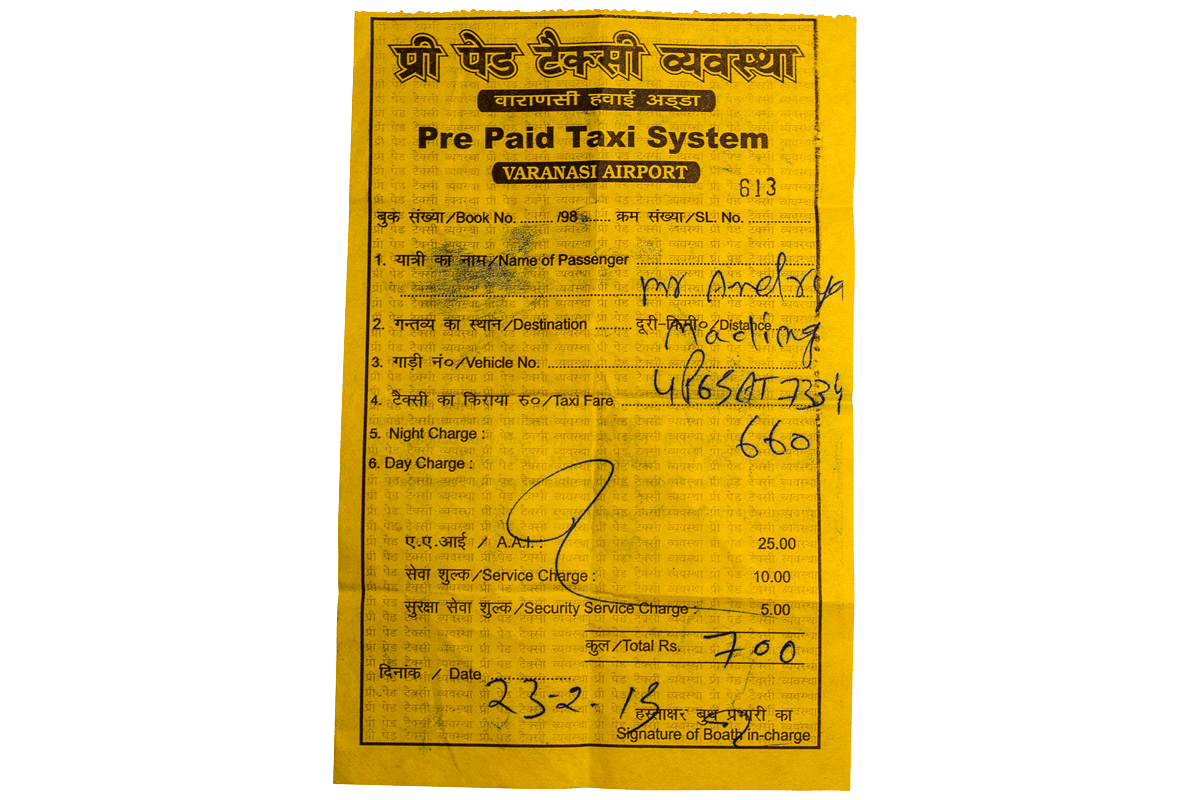

The distance from the airport to the city center is approximately thirty kilometers. There is no proper transportation available, so one has to take a taxi. And as it is known, taxi drivers tend to overcharge and deceive. To combat this, India has implemented a pre-paid taxi service managed by the police. The essence of this service is not to hand over money directly at the end of the trip but to prepay for the taxi at the counter and give the driver a signed receipt.

No matter how hard I tried to negotiate a fair price with private drivers and rickshaws, it didn’t work out. They kept changing vehicles every fifteen minutes, tried to make me pay half the fare upfront (claiming there was no fuel and they needed to refill), attempted to hand me over to a driver who didn’t speak English — but they didn’t want to let me go. They even tried to pull off the classic Indian trick with the hotel:

“I need to go to this hotel,” I show them the booking confirmation printout.

“Let me have a look. Ah, there’s a number here. Let me call them.”

“What for?”

“To ask the exact address.”

“No need, I’ll show it on the map.”

In reality, he wouldn’t have called to inquire about the address. Instead, he would have informed the hotel owners that I wouldn’t be arriving and canceled the reservation. Then he would have taken me to a hotel owned by his friends and received a commission for bringing a customer.

Desperate frustration was evident on their faces. Fifteen minutes passed without any success — none of their tricks worked. In the end, I ran out of patience, bluntly told them to go fuck themselves and headed towards the pre-paid taxi booth, ignoring the running Indian man shouting, “Please come back, sir!”

Pre-paid taxis cost twice as much, but they protect you from such harassers. Or so I thought until I arrived in Varanasi. Throughout the journey, the taxi driver was chatting with someone. It turned out he had made an arrangement with a “tour guide” to meet me and escort to the hotel since not every narrow street in Varanasi is accessible by car.

The tour guide turned out to be a young man in his twenties who warmly greeted and forcefully began escorting me:

“Are you from the hotel?”

“No, my father works as a taxi driver, and I’m helping him.”

“I understand. How much money do you want?”

“Oh, as much as you can pay,” In their language, it means 300 rupees.

“Alright, lead the way,” It’s impossible to resist them all day long.

Of course, the guy took me to a wrong hotel. I show him the printout and say, “Sorry, buddy, but I’ve already paid for it.” He nods and takes me to the right place, while showing the city and its waterfront that you fall in love with at first sight.

Along the whole waterfront stretch out simply unimaginable structures.

Fantastic. How many years these walls have been here? Any resident of Varanasi will mysteriously respond, “No one knows for sure.” In reality, these walls belong to the same type of fortresses scattered throughout India, and although they appear incredibly old, they were constructed between 1750 and 1800.

In fact, even the modern huts look good here.

Mountain goats.

On the ancient walls, they paint advertisements for hotels, yoga courses, and cafes. Despite its utter simplicity, this advertising looks like a work of art and fits perfectly into the overall landscape.

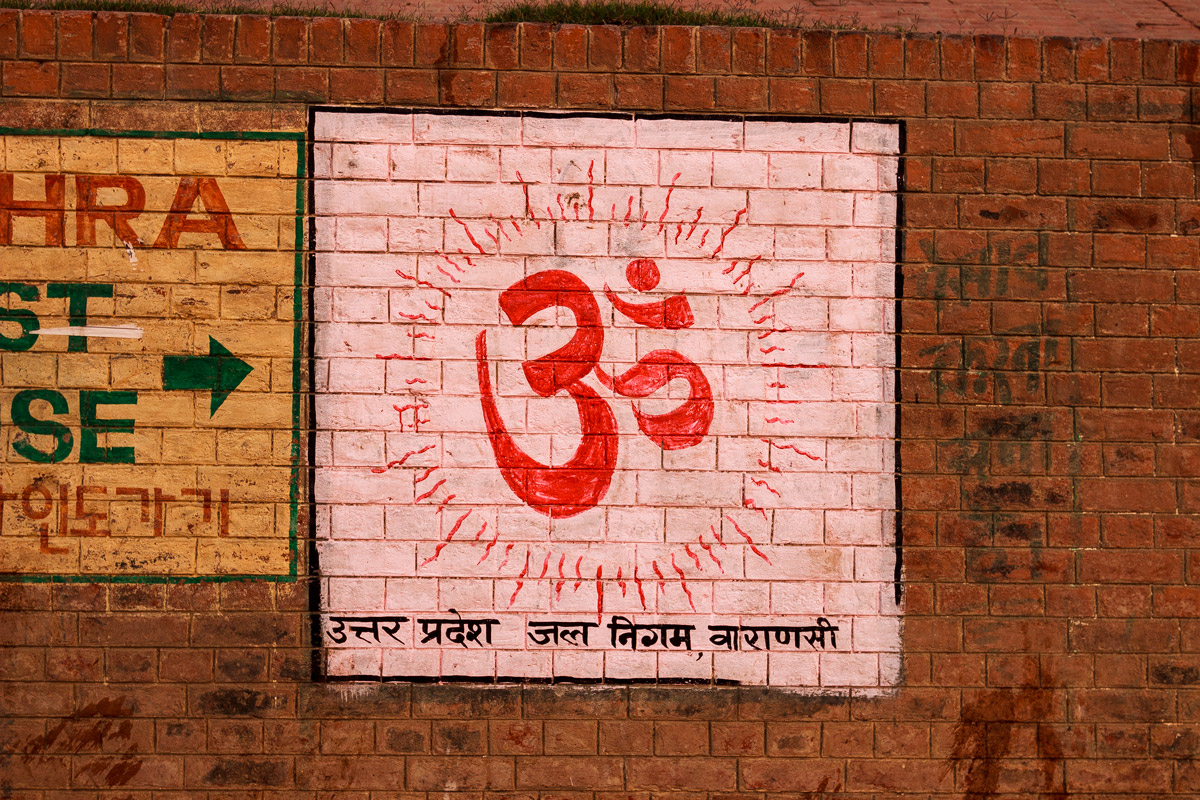

Many walls are covered with Hindu symbols. Om.

Swastika.

Shiva.

And, of course, Mother Ganga.

The striped steps near one of the temples look extremely photogenic.

Tent houses are set up along the river.

The guide first escorted me to the hotel and then persistently followed me throughout the evening, showing the best photo spots and telling about local features and attractions. He wasn’t much useful, of course. But I couldn’t shake him off — even if I tried to break away and get lost in the crowd, he somehow miraculously found me. And I didn’t really want to openly send him to hell since the situation around was slightly provocative.

On the way to the hotel, my guide asked me about many things, including a question whether I smoke hashish, to which I answered affirmatively. Not that my purpose of traveling to India was enlightenment through drug use, but Varanasi seemed like a special place: a holy Indian city, a center of ancient civilization’s traditions. Moreover, de facto, the sale of marijuana is allowed in special bhang shops in Varanasi, regulated by the police.

When the evening festival ended and it was already dark (in India, night always falls a little after 6 p.m.), the guide did not leave my side, escorting me back to the hotel. I didn’t mind his company. After all, it can be unpleasant and easy to get lost on the narrow winding streets of Varanasi at night. Not far from reaching our destination, my guide suggested entering a “very old temple.” I was surprised: where among these huts did he find a temple? I followed him to the second floor. Before me opened a dirty room with a cheap carpet on the floor, on which were sitting several people.

“What is this place?”

“Sit down, you’ll find out soon.”

You must imagine the author at that moment. Drenched in sweat, exhausted from a sprinting race through the streets of Varanasi and the festival, probably having slept only four hours for the second consecutive day, tired from the flight and arguments with touts, carrying a camera and tripod. And he suggests I sit on a dusty carpet in some house filled with Indians.

“I’m not going to sit down anywhere. Why did you bring me here?”

At that moment, I realize where and why they brought me. A thuggish-looking, short Indian approaches me, holding a huge chunk of hashish between his fingers, and says in a hushed voice, “Look at this! The best one, Afghani!” My first thought was, “Afghani hashish in India? Why not Indian hashish?” My second thought was more sensible: “I need to get out of here.” And it was absolutely the right thought because the brown chunk could have contained anything. For example, it might not have been hashish but opium. Murders are statistically rare in Varanasi, but thefts are not unheard of.

“Wow, that’s cool. I’ll definitely buy the whole chunk from you tomorrow. Just not today. I don’t have any money left, and look at me: I’m all sweaty, tired, and I want to sleep.”

“Come on, don’t be like that! You’ll smoke and relax. Come on, sit down!”

“No, guys. Seriously, I really love to smoke, but let’s do it tomorrow.”

The thug turned to my guide and started speaking in Hindi, gesturing actively. From their facial expressions and gestures, I could understand that the dialogue went something like this:

“Why the fuck did you bring him here? You said he smokes!”

“He told me that he smokes, so I brought him...”

The drug dealer turned to me and sternly ordered me to come tomorrow and buy a larger chunk. “Of course, I will,” I said. Then he shouted something loudly downstairs and told me to leave. As I descended to the first floor, I saw that the entrance was secured by an iron grille with a padlock. An Indian man, presumably a guard, approached the door, asked something to the thug, and unlocked the door for me. The guide showed me where to go, bid farewell, and instructed to be near the hotel at 7:30 a.m. so that he could continue showing me the city. To avoid trouble, I had to agree and figure it out on the next day.

Varanasi wakes up at 5 in the morning and begins its daily life with the sunrise.

A barber shaves his customer.

A janitor sweeps the trash.

Boatmen transport tourists.

A woman washes and dries the laundry.

Half of the entire embankment is occupied by laundry.

The laundry being washed isn’t theirs. The Varanasi embankment is a large spontaneous laundry, where clothes from the entire city are brought to be washed.

Every morning, hundreds of people descend to the Ganges River to take a morning bath.

They wash themselves well. Someone lathers their entire body with cheap household soap, and then, sitting on the steps of the embankment, scoops water from the Ganges River with their hand.

Someone wades into the water up to his waist or dives in completely. In the same position, it’s convenient to also brush teeth.

A little further away, burnt corpses are lowered into the same river. It may seem like these people are also washing laundry. In reality, they are rinsing the clothes and belongings of the deceased. On the right side of the photograph, is visible a bundle of orange fabric with a white sheet. It is a corpse lying on wooden stretchers.

Varanasi is a city of death. Thousands of followers of Hinduism come here to die. It is believed that the soul of a person who dies in Varanasi does not return to Earth in the body of another being. The cycle of births and deaths, the famous Indian samsara, has no power in Varanasi. The chain of reincarnations is broken once and for all for those who meet their death here, sending their consciousness to the transcendent world beyond matter and time — moksha.

According to Indian funeral tradition, the deceased are not buried in the ground but cremated on a pyre. Places for ritualistic cremations are located on the banks of sacred rivers and are called ghats. Varanasi is dotted with ghats along the entire Ganges embankment.

Photographing funerals is quite an activity. Firstly, it is not very ethical. Secondly, the locals can be hostile towards it. All Varanasi travel guides strongly discourage capturing the funeral process. The relatives of the deceased may vehemently oppose and behave very aggressively. Photographers may face threats or even stones being thrown at them.

Therefore, it is advisable to rent a boat and equip with a telephoto lens to capture the cremation from the river.

Boat rental for an hour costs only 300 rupees. A smiling Indian will gladly welcome you on board and take you along all the ghats.

Varanasi is beautiful with the Ganges. A true Indian city.

Clusters of houses, hotels, and ghats are all mixed together.

From the water, the walls of the fort are better discerned in these structures.

Gradually, the boat approaches the soaring spires of Indian temples, at the base of which lie enormous piles of firewood.

This is the famous Manikarnika Ghat, the largest active crematorium in Varanasi and in all of India.

Gathering of people. A group crowded at the top of the stairs consists of relatives of the deceased. Soon they will carry the corpse on stretchers, wrapped in an orange shroud.

Piles of tattered clothes amidst the pyres are the belongings of the deceased and those previously buried. In India, it is customary to bury a person along with all his belongings.

Burning firewood. Nothing remains of the body anymore.

Well, actually, something remains. If you zoom in on the photograph, you can discern bloodied legs peeking out from the smoldering pyre.

And here they are spraying water from a hose. They wash away the remains and ashes into the sacred Ganges River. A little further downstream, someone is bathing and brushing their teeth with this same water. Mother Ganges endures it all.

The boat approaches very close to the ghat, and here the boatman himself prohibits me from taking pictures. The captain paddles towards the shore, disembarking me right at the foot of the crematorium and handing me over to the tour guide.

“Hello! I work here as a volunteer, helping with funerals. Come, I’ll show you everything.”

“How much does it cost?”

“Whatever you’re comfortable with.” (Preparing to pay 300 rupees.)

The guide leads me into the inferno of Manikarnika, stepping over scattered firewood and coals, through piles of dirty debris. Smoke from the pyres and human bodies stings the eyes, but it doesn’t cut the nose or give off a burnt skin smell. It smells fairly tolerable, like a regular bonfire, with a hint of some ether oil. Apparently, they eliminate the odor by adding frankincense or other herbs to the fire.

“Look, there are three buildings here. These are hospices. Three hospices — three castes. The lowest caste, the middle castes, and the highest caste. Now we will go to the first hospice. People there await their death. Tell me, do you believe in karma?”

“Of course.”

“That’s very good. We all believe in karma. After all, everything material — money, possessions, luxury cars, expensive houses — is temporary. During your lifetime, you have it all. But a day comes and you lose it. Only one thing remains: your karma. It is eternal. It consists of your good and bad deeds. You cannot escape from karma.”

The guide initiates me into the mysteries of Indian funerals. People pass by me, carrying a stretcher with the deceased, chanting the prayer: “Ram naam satya hai.” Not far away, sits an Indian man in white attire; his head is shaved — he is the son of the deceased, assigned a special role in the funeral.

We approach the hospice, an unwashed building of swampy sand color with no doors or windows — only holes in the walls. The guide leads up the stairs to the second floor, where I would never dare to enter alone. The house resembles more of a hideout of Wahhabis in the mountains of Afghanistan.

On the second level, sitting on the floor — a terrifying, disheveled old woman. Next to her walks a young girl.

“This elderly woman is waiting for her death. The young girl is helping her prepare. Sit here.”

The guide seats me on the floor in front of the old woman. She extends her hands towards me and places them on my head. Closing her eyes, she begins reciting a prayer. The guide explains, “She is praying for you, wishing you happiness and good health.”

At that moment, I am briefly snapped out of this hypnotic sequence of events, and realize that I must turn on the camera. I manage to capture only a few seconds: scary.

The assistant repeats his story: “Karma is very important in our life. Some tell he has cars, house, money, but one day he has nothing. One day he has only karma”.

And then — at this very moment — the mystical universe of Varanasi reaches its highest point, apogee, absolute maxima, after which begins its drastic fall to the unfathomable depths of cynicism, avarice and hypocrisy.