Persepolis

To my horror, I learned that the ancient capital of Persia is now called not Persepolis, but Persepol. And with the stress on the second “e”: Perse-e-e-pol. Out of nowhere, huh? It’s clearly written in Greek — any person would read it: Περσέπολις. However, then we’ll have to say Constantinopolis.

In fact, the Greek name is a fabrication. Greeks often called Eastern cities by different names. There was never any Palmyra: the Syrian city was called Tadmor. There was never a Persepolis either: for a short period of time, it was called Parsa, but for over two thousand years, it has been known as Takht-e-Jamshid.

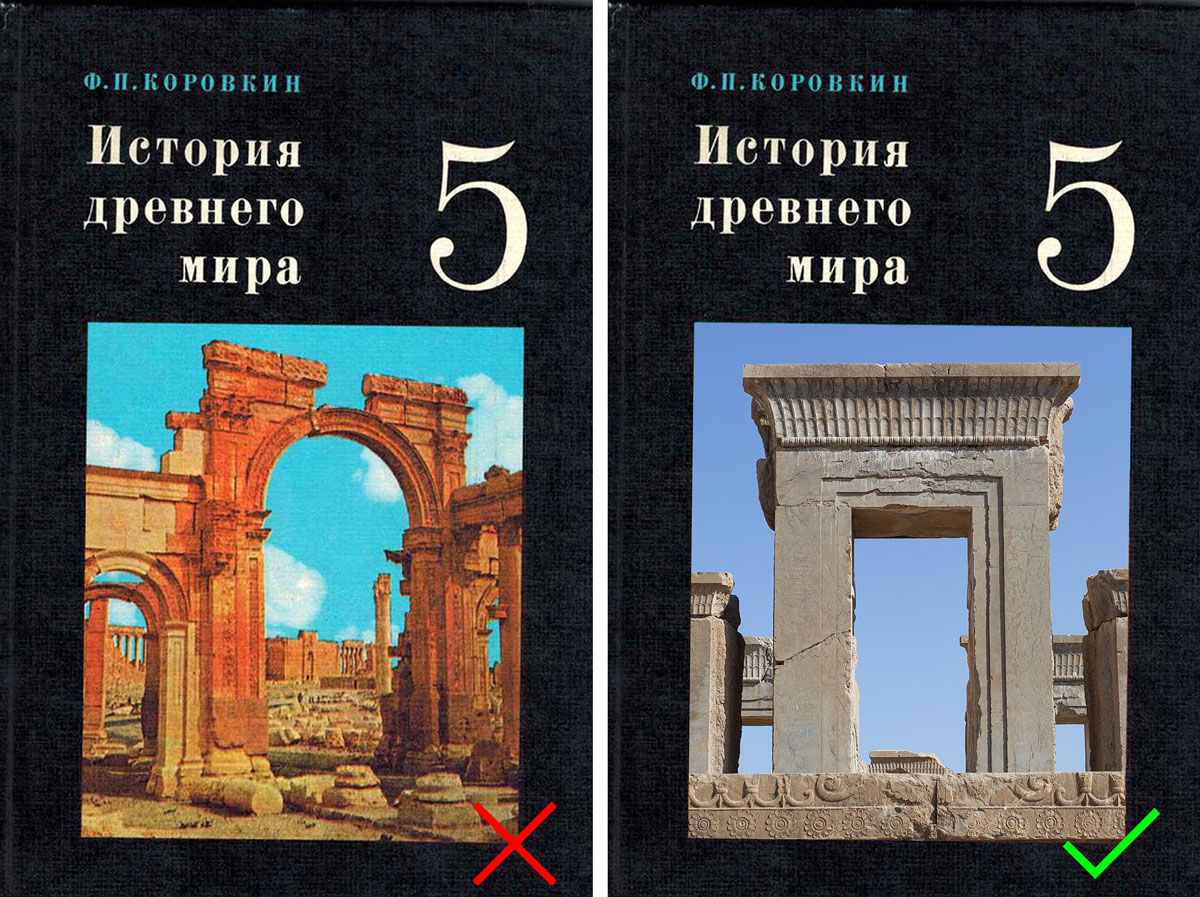

Unlike Palmyra, Persepolis never made it to the cover of a history textbook. There was little mention of it in the pages of school books. And that’s a shame. Although Palmyra was founded as early as -3000, the Roman columns and amphitheater only appeared in the 2nd—3rd century AD. The majority of Persepolis, however, was built by -500.

Persia has existed for many years and has undergone a dozen different governments during that time. Only a dedicated historian can remember them all. Initially, Persia was the Median Kingdom. Then came the Achaemenid dynasty, which ruled for 350 years until it was defeated by Alexander the Great.

Soon after that, Macedonia disintegrated, and Persia changed hands. At different times, Iran was ruled by the Seleucids, Parthians, Sassanids, Umayyads, Abbasids, Tahirids, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ilkhanids, Timurids, Safavids, Afsharids, Zands, Qajars, and finally, our beloved Pahlavis.

It is not entirely clear what all these dynasties did to the country, because Persepolis, which was founded during the Achaemenid era, remains the only truly cool ancient ruin in Iran.

By the way, the reader must have heard something about the Achaemenids, at least about King Xerxes. He’s the main villain from the movie “300 Spartans.” The name of King Darius the Great should also ring a bell. In fact, these two were the ones who built Persepolis entirely.

Darius initiated the construction. Persia was already a powerful and influential empire before him. It controlled the entire Middle East, Turkey, and Egypt. Darius conquered additional territories in India, Tunisia, parts of Greece, and annexed Crimea. Xerxes completed the construction with the superprofits obtained.

For some reason, a strong myth has formed about Persepolis being the capital of Persia. Guys, this is an unimaginable foolishness! Have you ever seen an empire’s capital in the 6th century BC located in the desert, without access to the sea or a river?

Persepolis was never intended to be a capital. The city was exclusively built as a public relations move to host ceremonies and showcase the empire’s power. The true capital of Persia was in Babylon, and the second one was in the city of Susa.

⁂

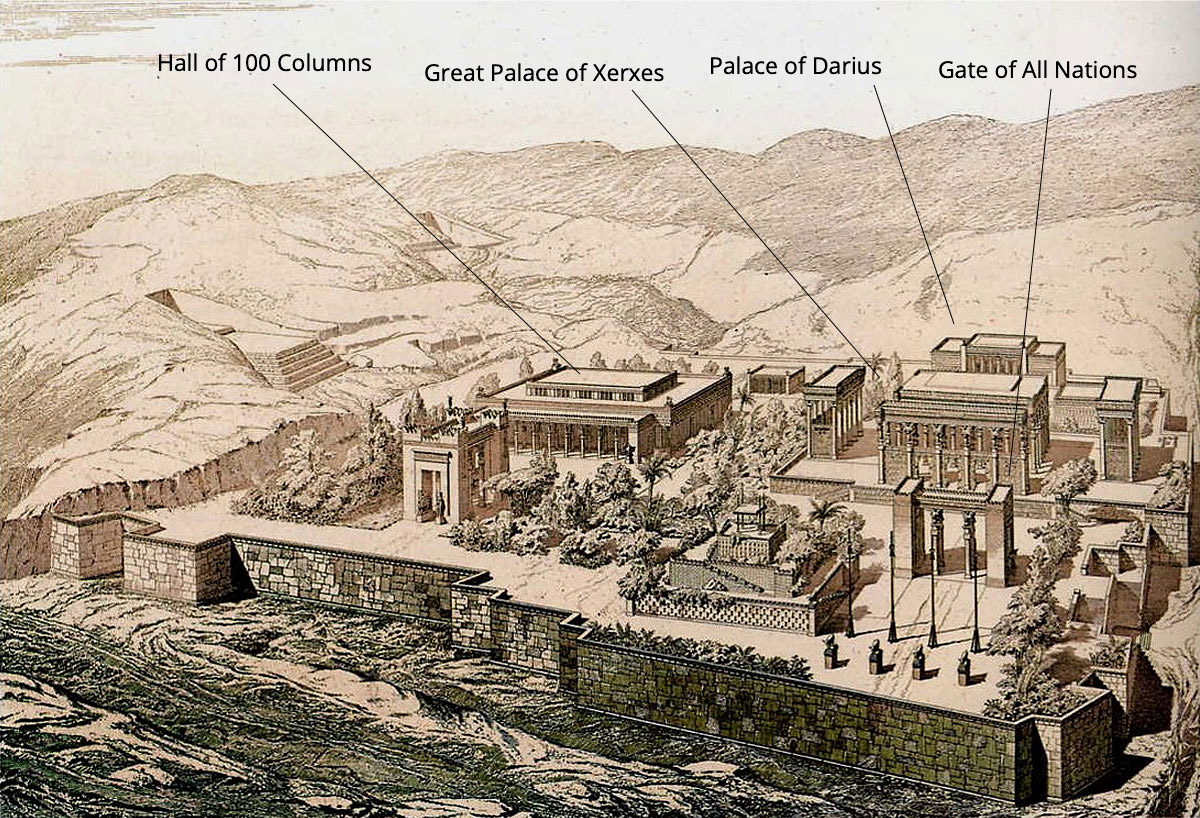

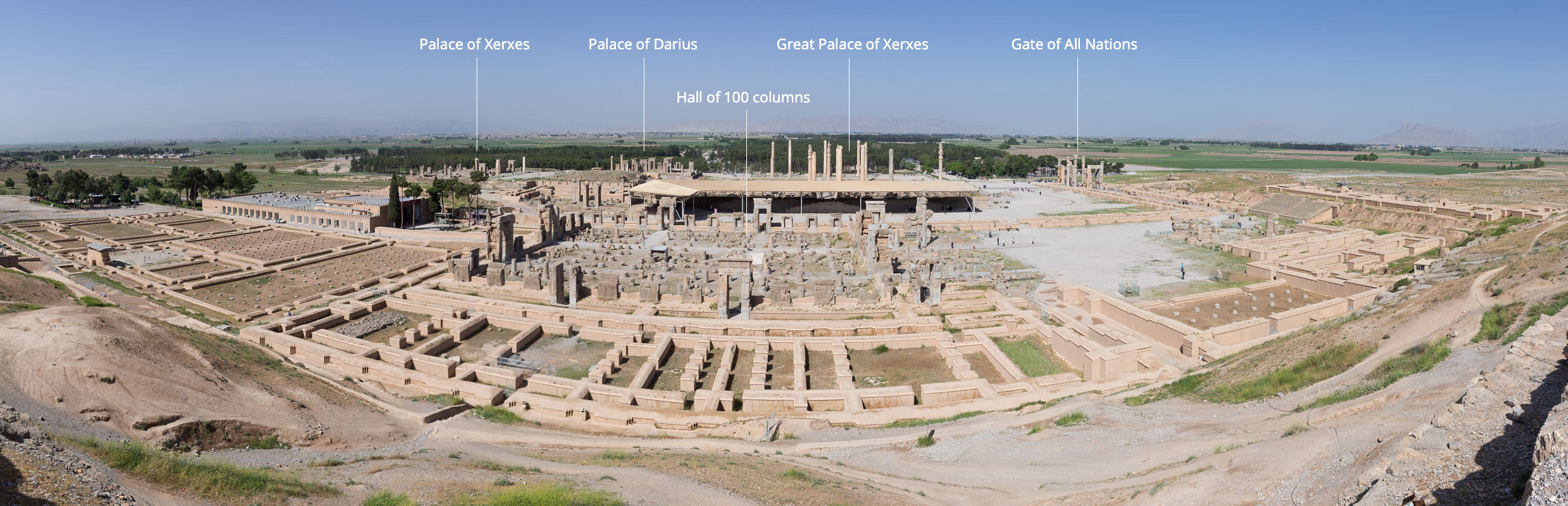

Persepolis fits quite compactly within the view from the nearby hill.

The city begins with a gigantic ceremonial entrance that is about a kilometer long.

Xerxes built the entire entrance ensemble. Besides the metal detector frames, they were installed by the Iranian FSB to prevent terrorists from carrying a bomb in their pockets and detonating Persepolis like Palmyra.

The 2,500-year-old staircases are, of course, covered with wooden planks, but they have been perfectly preserved.

The ceremonial entrance to Persepolis is called the Gate of All Nations. Such grand entrances with columns and statues are known as propylaea in ancient architecture.

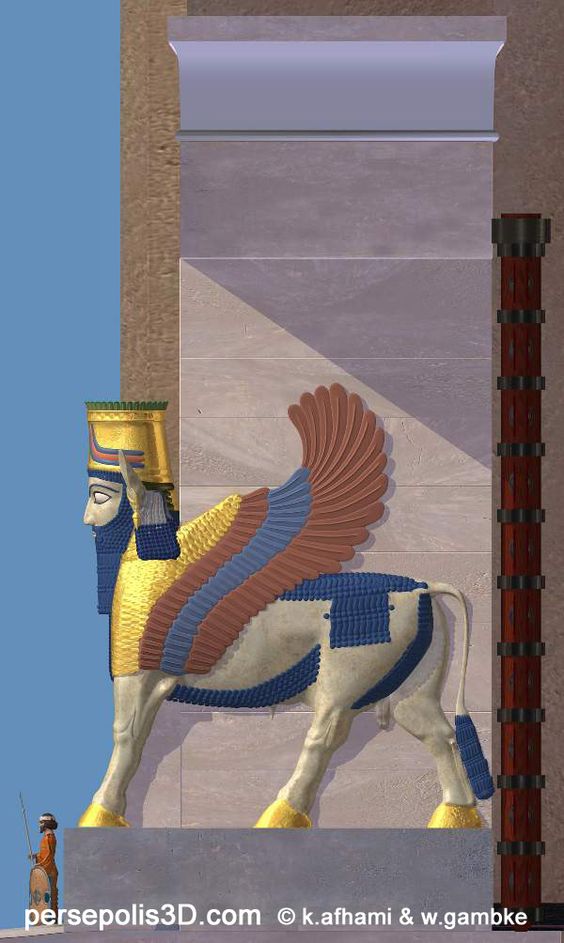

The entrance columns depict Lamassu, winged human-headed bulls. It is a typical stone architecture of medieval Mesopotamia. They are like guardians of the entrance.

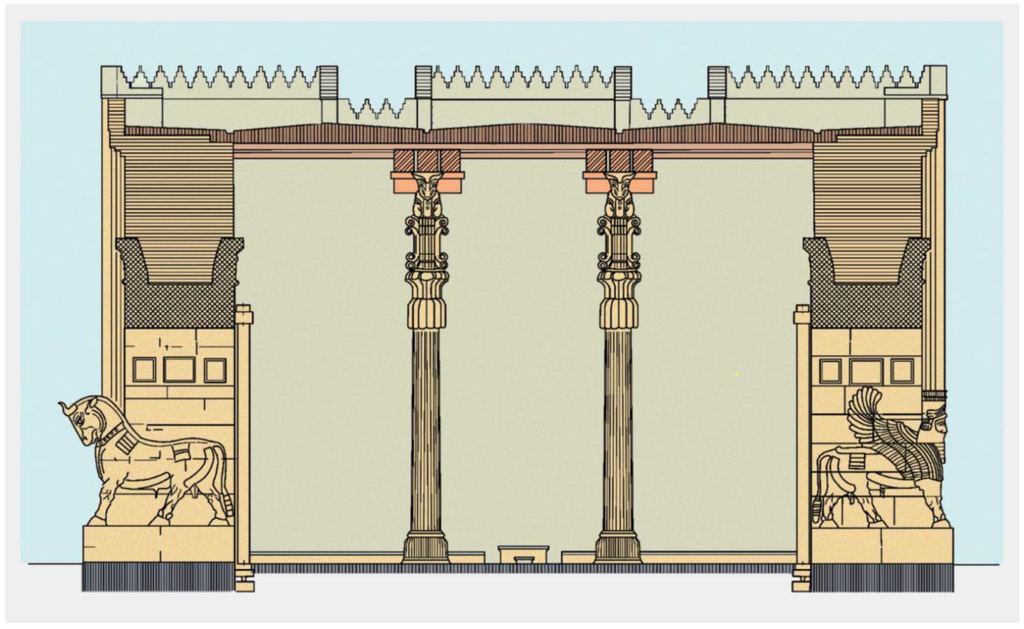

Such sculptures stand symmetrically on both sides: at the entrance and at the exit. There are also two pairs of round columns between them. Remember, soon it will become clear what they are for.

Historical-glycogenic folklore in the best traditions of Persia. It seems that such things were known to Vavilen Tatarsky in “Generation Pi” when he overate mushrooms.

The first impression is that the gates have been preserved very well, but it’s just an illusion. In reality, propylaea are almost always covered structures. And it was precisely the roof from Persepolis that got blown off. Remember that the sculptures stand symmetrically on both sides? Remember that there are also round columns between them? Well, the roof was resting on all of that.

Two and a half thousand years ago, the entrance to Persepolis looked like this:

And also, all the sculptures and columns were painted. Yes, yes. Both Greek temples and Roman statues — everything was once colorful, and the paint job was absolutely nauseating. Fortunately, the paint did not survive.

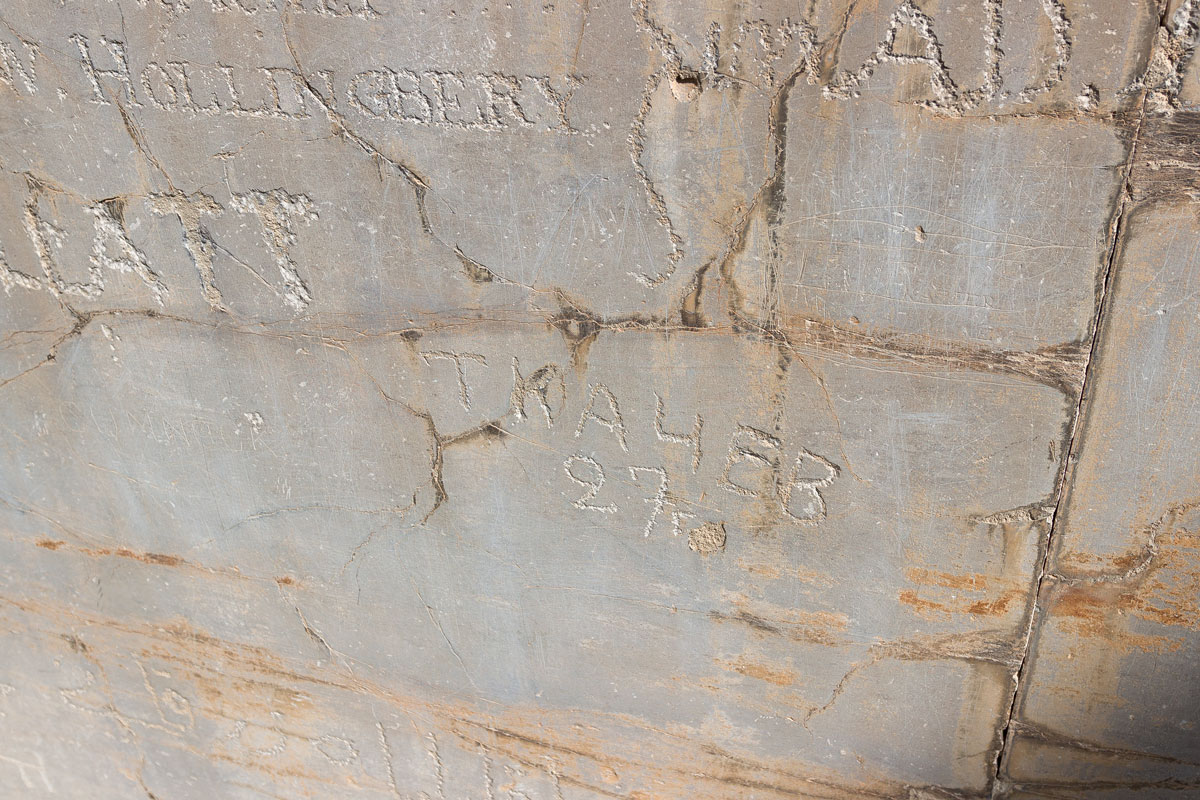

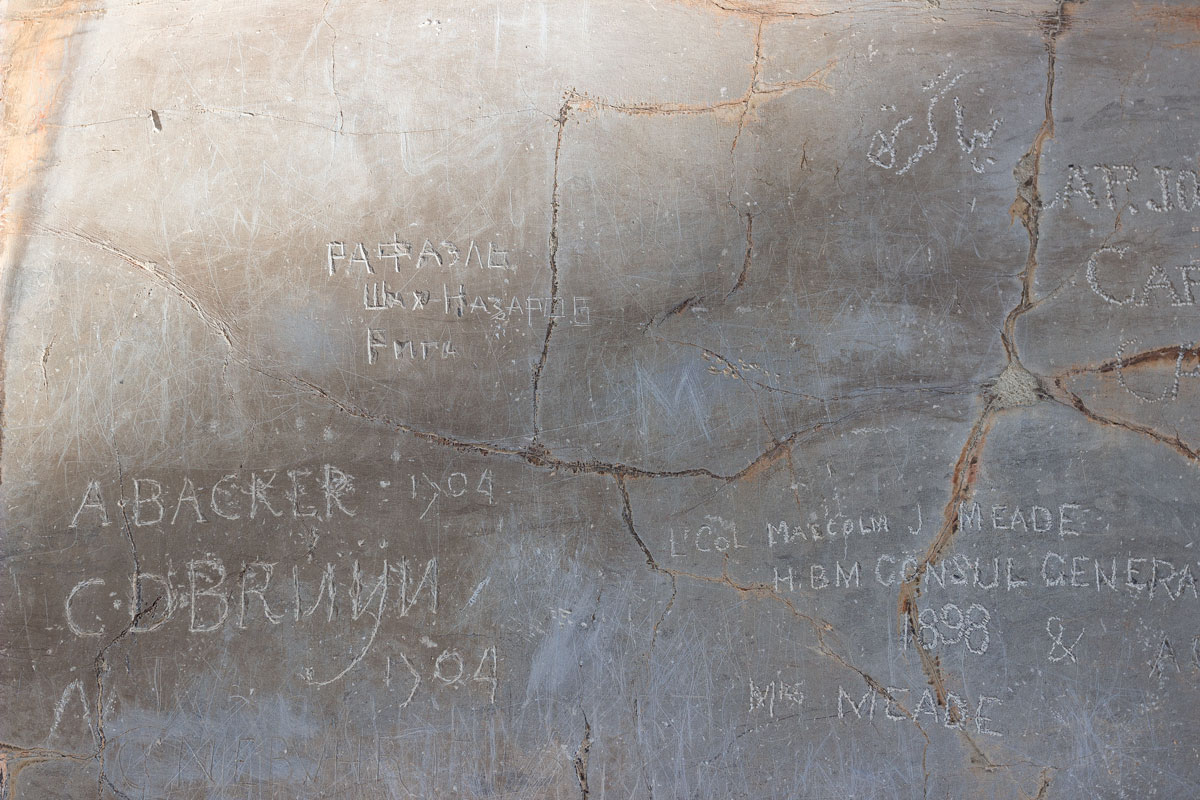

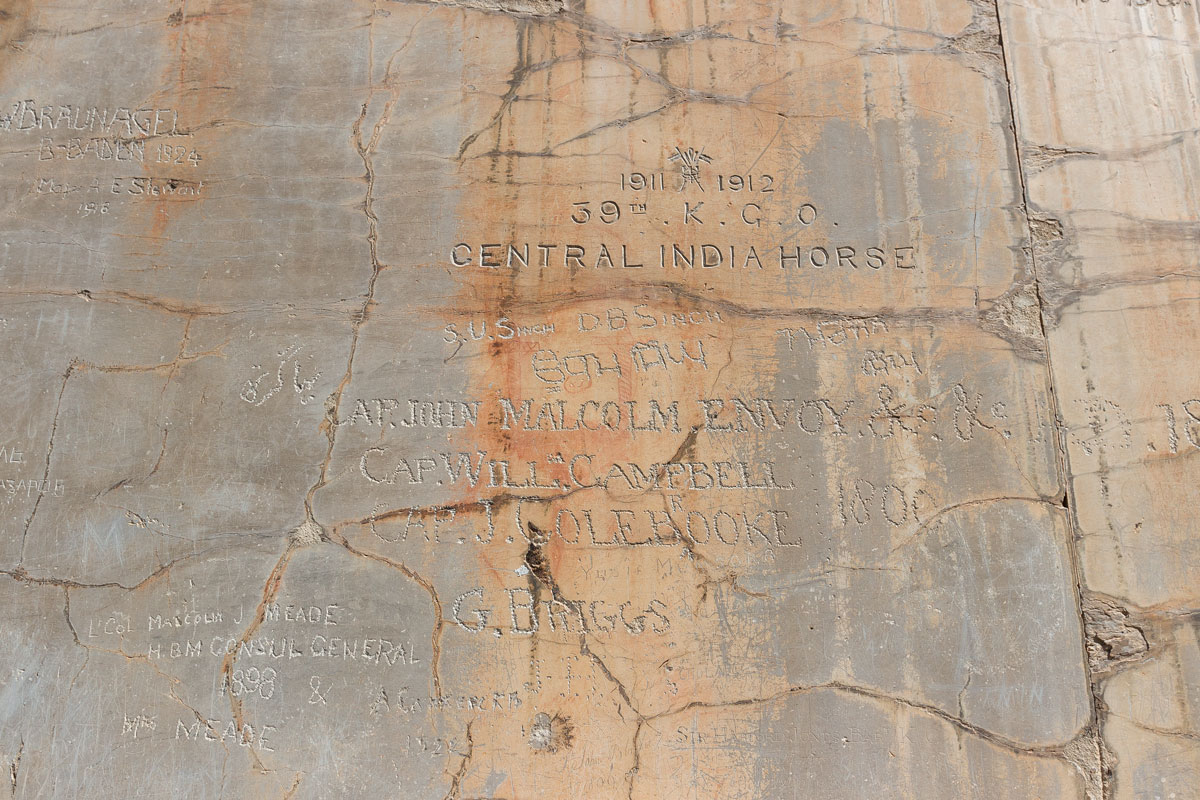

But what has survived are the historical inscriptions on the gates. From them, we can learn that Persepolis was visited by: Soviet citizen Tkachev in 1927, Danes Baker and Bruun in 1904, as well as Riga resident Raphael Shahbazyan (the dating is being established by archaeologists).

It seems that in the early 20th century, the gates of Persepolis served as something like autograph boards. Here, notable mentions were made by: the Central Indian Cavalry, a trusted representative of someone named John Malcolm, Captain William Campbell, and others.

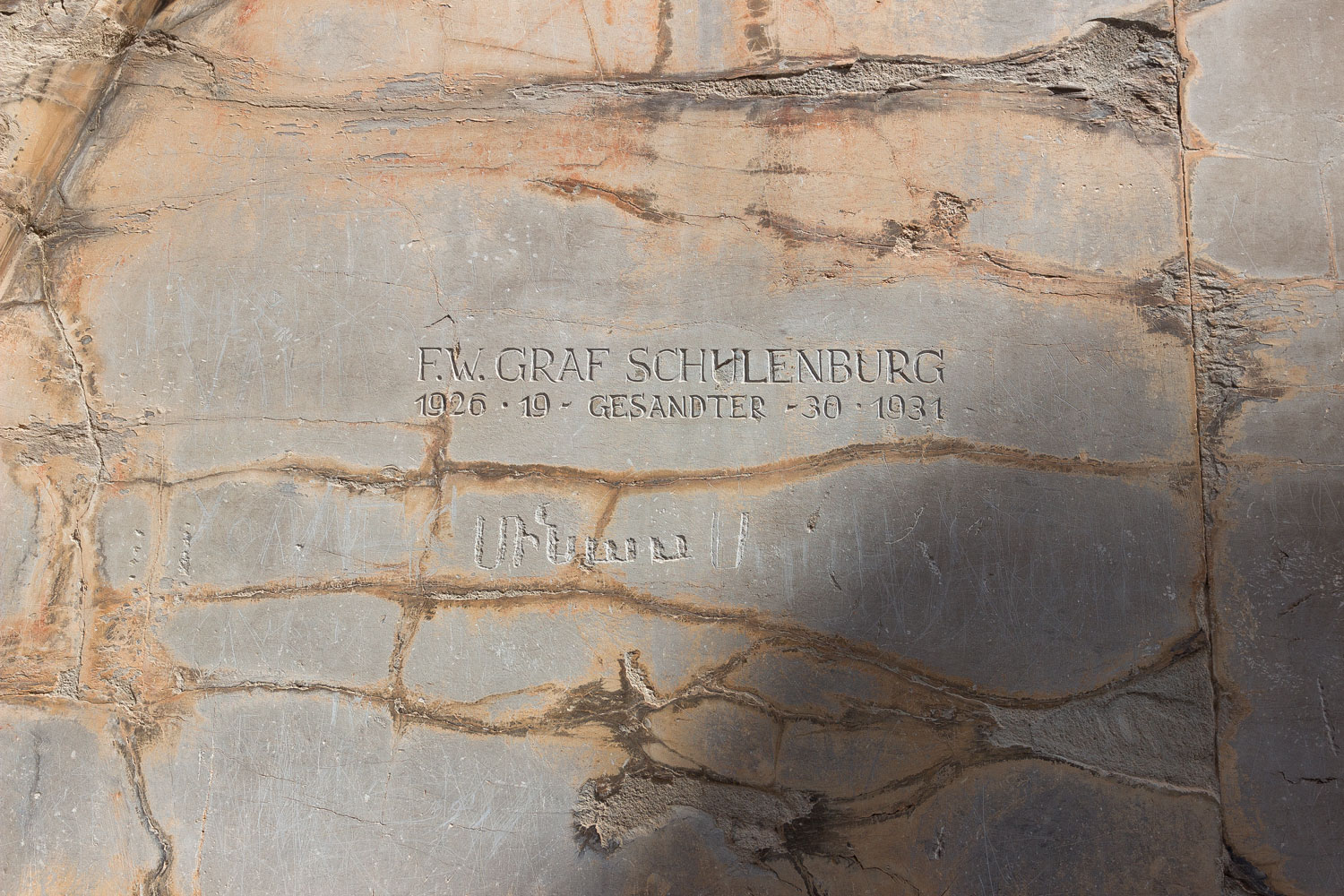

But the most important person, of course, was Schulenburg, the ambassador of the Third Reich in the USSR. He was also an ambassador to Iran at one point and had a great fondness for visiting Persepolis.

If the reader remembers, in the first chapter of the story about Iran, I explained how Hitler recognized the Persian people as true Aryans. Therefore, leaving such an inscription on the gates of Persepolis was an honor for Iran. Look at how precisely it is engraved, unlike all the others.

The propylaea led to a wide street intended for the ceremonial procession of the Persian army. Two rows of stone slabs served as bases for tall walls that framed the street.

In the background, the main part of Persepolis is already visible — the giant columns. This is all that remains of the Great Palace of Xerxes.

The columns — the main delight.

The walls of the palace collapsed because they were made of straw-reinforced bricks, similar to those used in the clay houses of old Yazd. However, the columns were carved from stone. That’s why only the columns from Persepolis have survived.

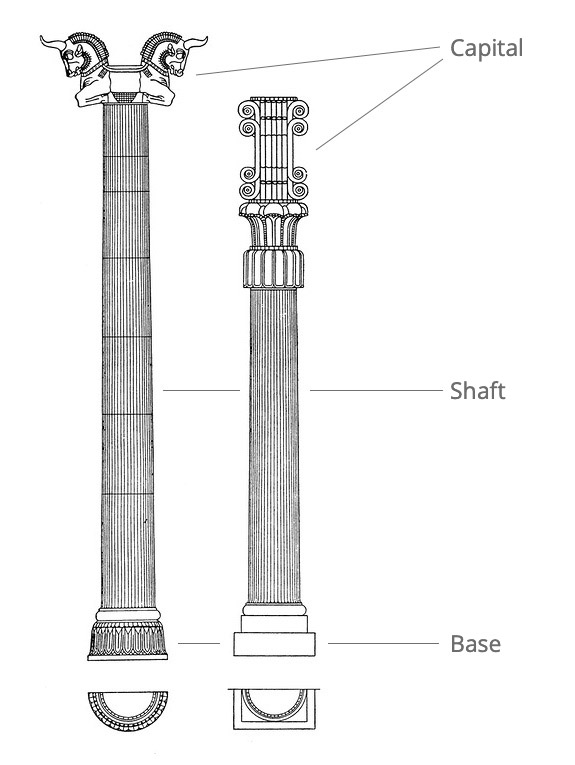

By the way, a column consists of three parts: the base, shaft, and capital.

Persian columns have an interesting base. I just can’t understand what is depicted on it. Some say it’s unopened lily blossoms. In my opinion, they look like the buttocks of dancers.

The shaft of the Persepolis column is unremarkable. By the way, those grooves along the shaft are called flutes.

And the capital — the top part of the column — is an extract of grandeur.

The capitals in Persepolis were of two types. Either there was a complex structure of volutes on the top of the column, or a double bull’s head.

Something tells me that some columns had both volutes and bull’s heads. It’s difficult to determine from the ruins.

The columns, like the gates, appear to be well-preserved.

In reality, that’s not the case either. Nothing remains of the palace. The columns didn’t stand on their own in an empty space; they supported the roof.

The bulls on the capitals and the columns themselves were, of course, also painted in garish colors.

From the reconstructed models of the palace, it is immediately evident that its purpose was to accommodate delegations and ceremonies. There was no emphasis on comfort, just columns and a roof.

Behind the palace, secondary ruins begin. It seems that somewhere around here was a banquet hall.

Well, they wouldn’t just depict plates and sheep on the reliefs for no reason.

Next to it is the Palace of Darius.

Different sources constantly confuse to whom the ruins belonged. For a long time, it was believed that Darius’ palace was right there in those large columns. Then it turned out that the columns remained from the ceremonial hall, and Darius had a modest room.

The large arches with openings are doors and windows.

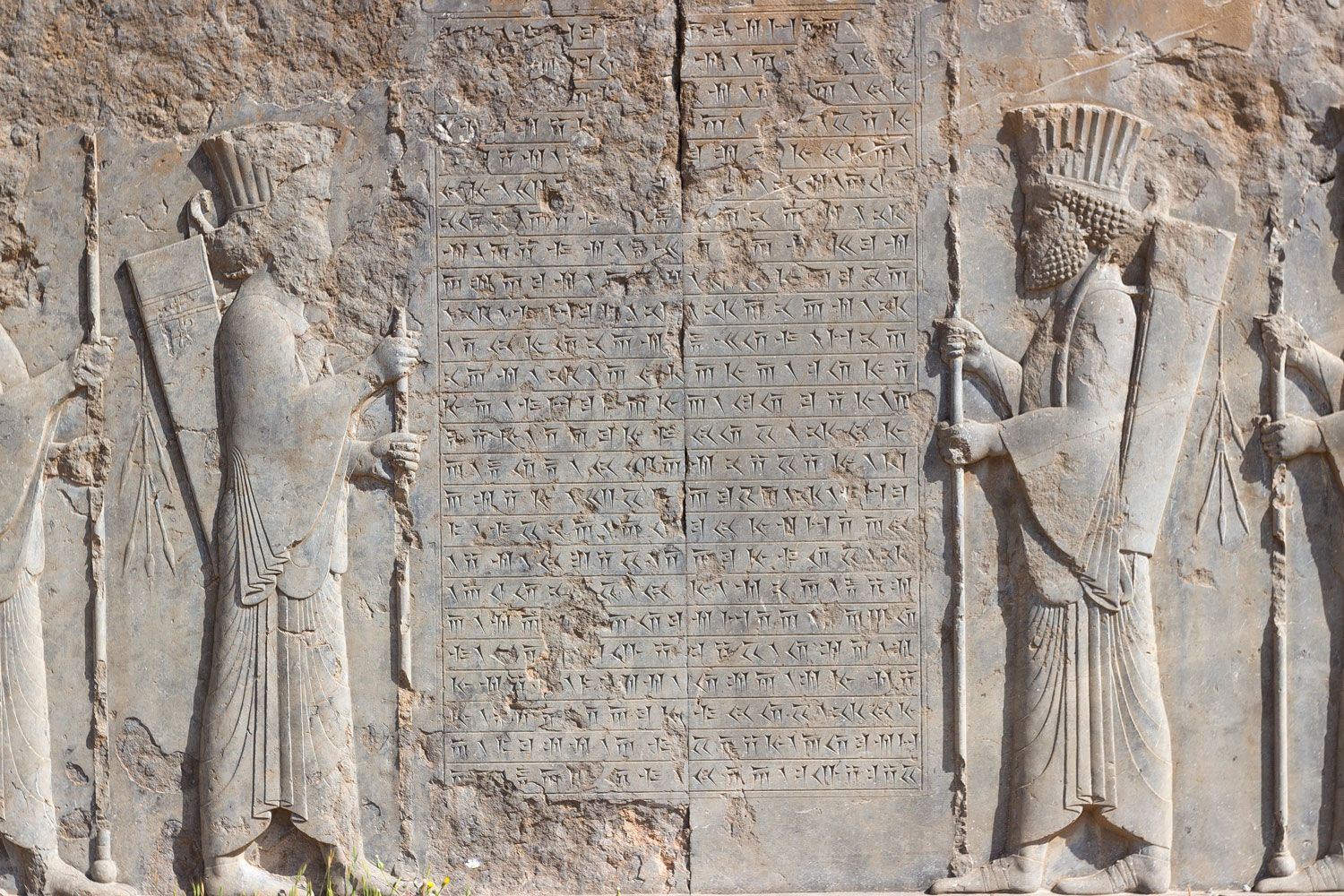

The bas-relief on the palace foundation is mind-blowing.

This is the Ancient Persian language, one of the rare written monuments of that time. The reader may look and say, “Cuneiform!” Exactly, but cuneiform is a writing system, and the language recorded in cuneiform is Ancient Persian.

The final part of Persepolis is the Hundred-Column Hall. It is best viewed from the hill that adjoins the city.

Oh, where is the hall with the columns? Sure, they have crumbled over of two thousand years!

⁂

In the summer of -331, Alexander the Great crossed the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and approached Media, the heart of the Persian Empire.

In the same year, under the army of the Macedonian, ancient Babylon and Susa, two capitals of the empire, fell. Until then, the Greeks knew nothing about Persepolis, which once again speaks to the meaninglessness of these palaces in the desert.

After crossing the mountains, Macedonian reached Persepolis. The first attempt to storm the fortress failed, but shortly thereafter, a second attempt followed, and Persepolis fell. The Macedonian army wintered in the city, waited for spring to arrive, and then moved on.

The ancient city of Persepolis was plundered, burned, and destroyed by Alexander the Great in -300. It was his revenge on Xerxes for capturing Athens 150 years earlier.