Tehran

Tehran is the Iranian capital, a rather dull metropolis gradually engulfed by residential districts. In many ways, the city resembles Moscow. Where it is not, there it is similar to Arab neighborhoods. Therefore, we will not stay here for long.

I immediately want to see Tehran from a height. Closer to the outskirts of the city, just like in Moscow, stands the Burj Milad TV Tower with an observation deck.

Before the visit, a lovely Iranian woman in a hijab tells: the tower was built in 2007, it is the 6th tallest building in the world, and at the top, there is a rotating restaurant with two different types of coffee.

The view of Tehran from the tower immediately clarifies everything: the city is not wealthy, but it is green and well-populated.

The majority of Tehran is built with five-story buildings, but unlike Moscow, the typical Tehran “khrushchyovka” usually consists of a single entrance, not three. Arab influence can be seen in the urban development: such variations in height and the pattern of “street-building-street” would be unacceptable even in Soviet planned construction.

Tehran’s problems are also similar to those of Moscow: the city is gradually encircled by panel high-rise buildings, and giant highways cut it into sections. In the foreground are expensive private houses with access to parks.

In the north of Tehran, it meets the mountain range of Tochal, which separates it from the Caspian Sea. The mountains provide an excellent view of Tehran.

Somewhere on Tochal, there should be an excellent city viewpoint, as well as a well-equipped ski resort with a cable car, all within a three-hour reach from the city center. Unfortunately, first the smog and then the rain hindered reaching there. It should look something like this:

But let’s come down from the heavens to the ground.

The first thing that catches the eye upon arrival in Iran is not a desert at all, but a blooming green country with a mild climate. Trees are always planted along the streets. Cities always have several parks of European standards.

Here are typical streets in downtown Tehran. Here we can see all the attributes of a normal life: sidewalk tiles, tactile pathway for the blind, well-dressed people, green trees, and a traffic jam.

Just a slight turn from the main streets, and Tehran becomes more reminiscent of a typical Arab city. The already narrow sidewalks are filled with road signs and lampposts, cluttered with motorcycles, while the sides of the buildings are pressed against endless shops, stalls, and eateries.

Usually, there aren’t too many people on the streets of Tehran, but in certain “bazaar” parts of the city, crowds of people surge, and the number of motorcycles rivals that of Delhi.

Due to haphazard parking, narrow streets in Tehran often experience traffic congestion. Dilapidated houses, mostly adorned with store signs and advertisements, loom heavily over the traffic jam.

But there is no need to fear dilapidation. In this sense, Tehran is very similar to the Vietnamese city of Hanoi. If all this mess is cleaned up and stripped of advertisements and air conditioners, some rather decent architecture will unexpectedly emerge from beneath the dirt.

If you carefully scrutinize this dilapidation, you can spot true gems within it. For example, like this bas-relief on the facade of an old theater. It is utterly impossible to imagine an image of a woman’s breast in any Arab country, and cultural artifacts like these distinguish Persia from Arabia.

Another house turns out to be a splendid mansion from the time of the first Pahlavi Shah. It is now occupied by a chandelier store. The sign on the store reads: “Bazaar-e Lustre Tehran.” The word “lustre” (chandelier) has been borrowed into the Persian language from French, just like “bilet” (ticket), “bakaleh” (grocery), “mersi” (thank you), and many other words.

By the way, about chandeliers.

Imagine a reasonably long but not overly wide street in Moscow. For example, Malaya Bronnaya Street. Now, imagine that on both sides of Malaya Bronnaya, there is a continuous wall of houses, and each house on the ground floor sells chandeliers. Moreover, these chandeliers are of such sizes that they wouldn’t fit into any apartment in the houses along Malaya Bronnaya.

The main mystery of the East is who and for what reason needs so many gigantic chandeliers?!

Instead of chandeliers, of course, it could be any other merchandise. Various cabinets, all sorts of chests, assorted chairs, different samovars and teapots, diverse toilets. The important thing is that entire streets are cluttered with the same merchandise in colossal quantities.

There is a good proverb about the Western and Eastern approach to business. If a gas station opens on a newly built highway, an Arab will open a second gas station nearby, while an American will open a store.

So, once upon a time, someone opened the first chandelier store in Tehran, and it took off. Now the city is divided based on the principle of a bazaar. On each street, they sell a specific product, and identical stores stretch for kilometers.

There are real bazaars in Tehran as well, but they will only appeal to those who have never seen Eastern bazaars in other countries.

There is no truly Persian market in the capital; you have to go to Isfahan for that (and we will definitely go there). Only occasionally you come across shops with colorful shop windows filled with copper teapots and engraved plates.

Vibrant scenes are always captured in shops with spices and fruits.

The Tehran Grand Bazaar is like regular city streets, but with a roof. The shops are open on the ground floors of buildings, and the merchants live in those very buildings.

That’s how it’s done in the East: you wake up in the morning, go down to the ground floor, open your shop, and sit there until evening. Eastern markets, and any shops for that matter, open directly from the house, from the apartment. That’s why everyone here knows each other and shares customers.

The busiest rows in the Grand Bazaar run along its border with the wide Panzdah-e Khordad Alley. It seems that food festivals or something similar are organized here during holidays.

This pedestrian zone is always crowded with crowds. The most expensive stalls of the bazaar are located right here, and they mainly sell spices, fruits, hijabs, and small electronics — the essential grocery set of a modern Iranian.

European clothing is also popular in the bazaar. For example, there’s a store called Nike. Oops, I apologize, that’s actually the Persian letter “m” written in cursive. Nevertheless, everyone here wears European clothing. The author even noticed a biker wearing a t-shirt with the US flag.

It soon becomes clear why the alley is so popular — several of Tehran’s largest mosques are located on it.

Pay attention to the artwork on this minaret. It is another example of Kufic calligraphy, which I mentioned in the overview article about Iran. On the building itself, there is simple Arabic calligraphy.

The alley connects with a row of ministries, palaces, recreational areas, and simply historical quarters of Tehran.

An antique mansion, seemingly from the beginning of the 20th century. It has a beautiful style. Let’s call it Persian Baroque — I’m not particularly knowledgeable about architecture.

Under the roof, among other decorative elements, a winged angel Faravahar can be seen — a symbol of the ancient Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism. It is remarkable that the Islamic Revolution did not completely demolish the reliefs of women on the walls of theaters nor the “pagan” gods from the royal estates.

Unfortunately, there are not many well-preserved houses left in the city. They all need to be sought out, finding the right angle for capturing them.

Only one place in Tehran is prepared for tourist visits — the Golestan Palace. It was once used for the coronation of Reza Pahlavi and diplomatic receptions.

The golden rule is that everything prepared for tourists in the East is monstrously boring and uninteresting.

Well, it is beautiful, no doubt.

But what’s the point of seeking beauty in a place where it is put on display?

The former Shah’s residence is a completely lifeless, static, and artificial place.

Inside, it’s even worse. The wooden parquet resembles what was laid in Khrushchev-era apartments. Modest rooms by Kremlin standards are covered with either glass or diamonds — in such quantities that their shine could trigger an epileptic seizure. Expensive chandeliers hang from the ceiling. We know where they come from.

In general, it’s boring. It’s much more interesting to search for emeralds among the rubbish that people pass by every day.

But the main object in Tehran is the famous American embassy, which was destroyed during the 1979 revolution. At that time, the Islamic followers of Imam Khomeini took 66 people hostage and released them only after a year and a half.

The embassy still stands in the center of Tehran and has been turned into a museum. Anyone interested can enter and see how everything is arranged inside. At the entrance, they ask for your country. If you’re from Russia, they will be doubly pleased to show you the den of the common enemy. If you’re from America, it’s interesting to wonder what they will say.

America is hated here. And I really love people who hate America — they are always so endearing. That’s why the museum guard, after asking where I’m from, just said it straight out: “I hate America.” In English. After that, he buried himself in Google on his Android smartphone. There was a Snickers kiosk next to the ticket office. Yum-yum-yum.

The walls of the fence are covered with graffiti of varying quality.

The inscription above the entrance reads: “Museum-Garden of Anti-Arrogance. Okay.

The embassy building is a luxurious mansion, where even the columns at the entrance resemble the White House in some way. The building is surrounded by a vast garden — it turns out that all major embassies in Tehran are so grand, dating back to the time of the monarchy.

In the embassy courtyard, there is a permanent exhibition showcasing openly anti-Semitic and anti-American works.

On the poster to the right, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is depicted in the style of Colonel Sanders from the KFC logo, but with the restaurant name changed to KPC. At the bottom, there is a poorly written and forced decryption: “Killer Palestine Children.” The authors do not explain the connection between Netanyahu, chicken wings, and Palestine.

The poster on the left claims that Iranians love Israel because they hate Islam.

And so, all the works are a display of tastelessness. It is clear from them only that there is a strong hatred for Israel and the USA in Iran. Why this is the case, they cannot explain.

The BBC poster with the caption “Sponsor of terrorism” — on what basis? In the poster with the phrase “He wants us,” written with a mistake (should be “he wants”), the word “US” is inexplicably highlighted. It turns into “He wants the USA.” Persian cynics lack even a milligram of self-criticism and fail to see obvious flaws in their works.

Inside the embassy, there were typical Soviet-style corridors painted in green. The Statue of Liberty on the wall is the creation of the rebels.

The poster depicting the Statue of Liberty shooting down an Iranian plane. It refers to the event of 1988 when a civilian Iran Air plane was shot down by the US Navy. Interestingly, despite the openly hostile relations between the countries, America paid $131 million in compensation to the victims’ families.

Not too many secrets were found in the embassy. The most interesting item was a teletype machine for sending encoded messages, TSEC/HW-28. No information or any mention of this model could be found.

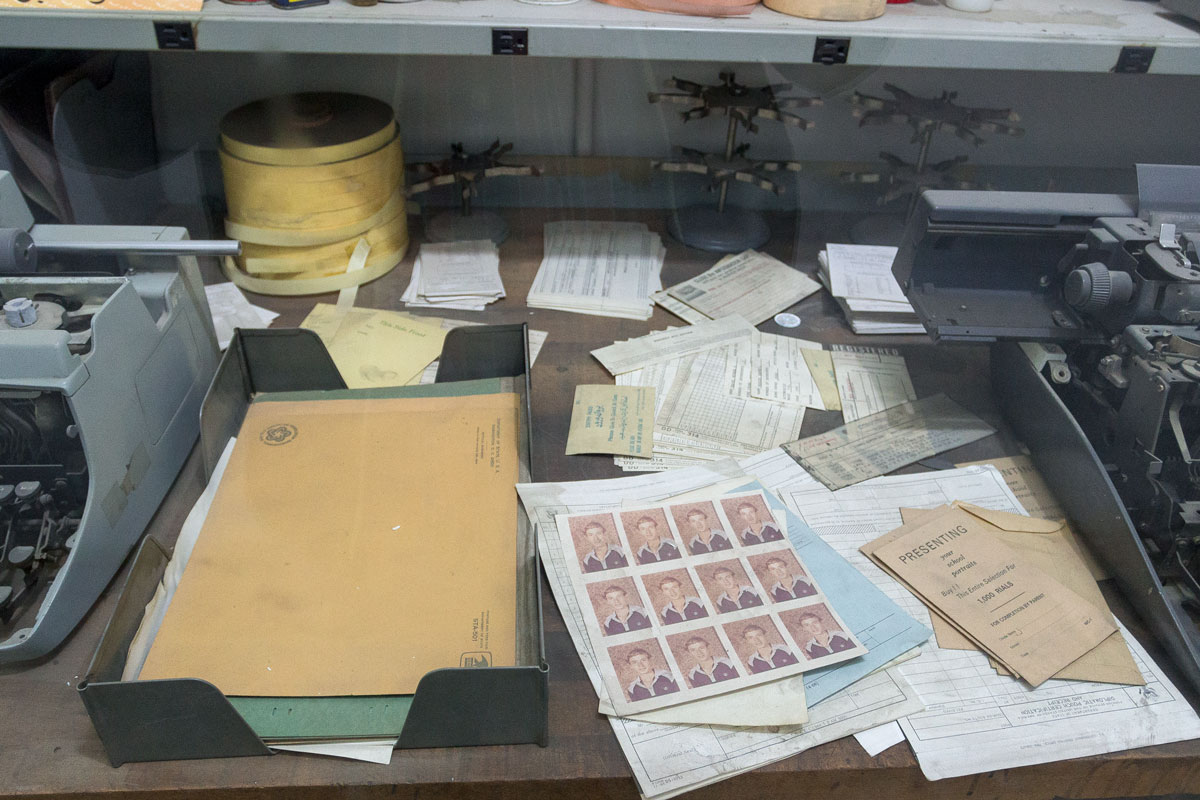

The revolutionaries got hold of the entire contents of the passport desk, including the visa stamping machine.

The workstation of the visa officer.

Soundproof room for confidential negotiations.

Secret room with confidential cabinets. Didn’t understand what was inside them, but judging by the thickness of the door, it was something important.

There were also plenty of cabinets in the embassy that resembled old PBX systems — presumably, these are devices for encrypted telephone communication, teletypes, radios, and other communication equipment.

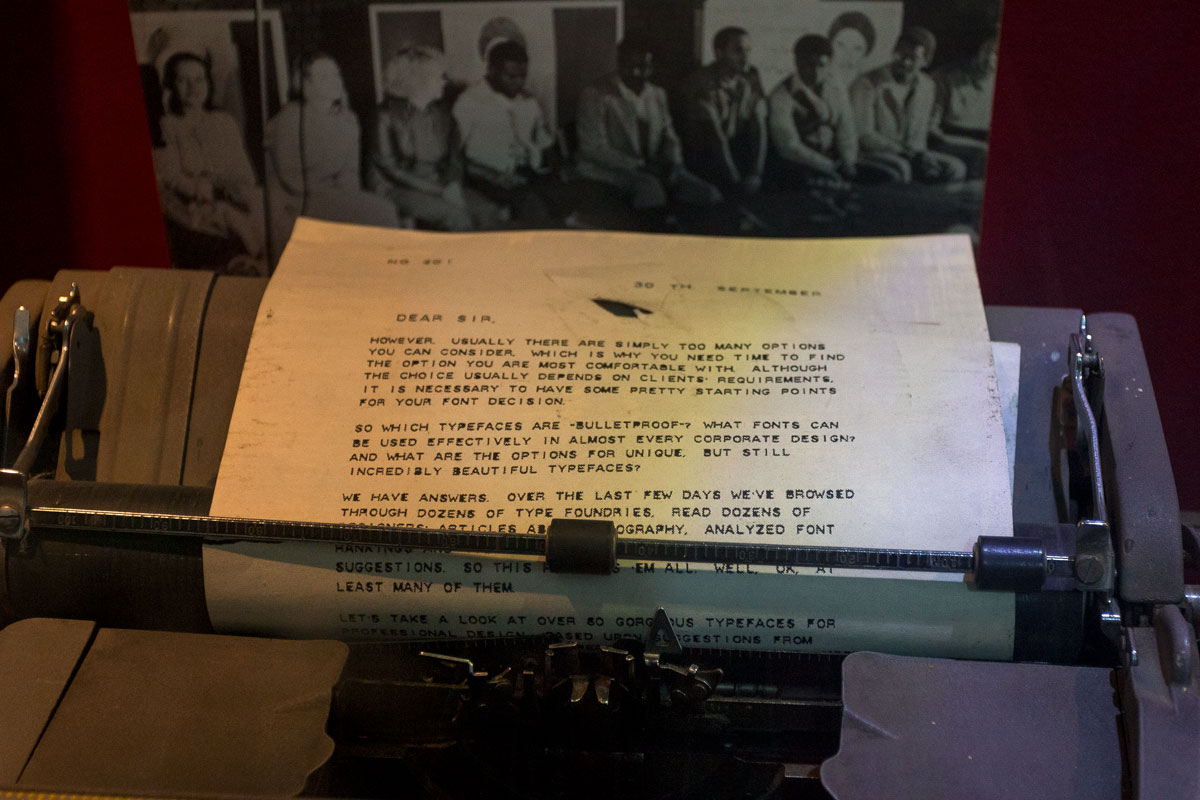

The revolution caught the embassy staff off guard. Secret documents with incredible facts fell into the hands of Iranians. For example, according to the text of this letter, undercover agents were caught in the act of plotting against the government. The filthy imperialists coordinated a branded typeface with the State Department.

In reality, at the moment of the consulate takeover, the Americans urgently began destroying secret documents. All of this was very similar to the recent eviction of Russians from the consulate in San Francisco. Back then, black smoke started billowing from the chimney of the Russian consulate.

Apparently, Russia had a similar situation to America in Tehran. At the most critical moment, the paper grinder, which turned documents into dust, malfunctioned. Therefore, the Americans had to use a regular paper shredder.

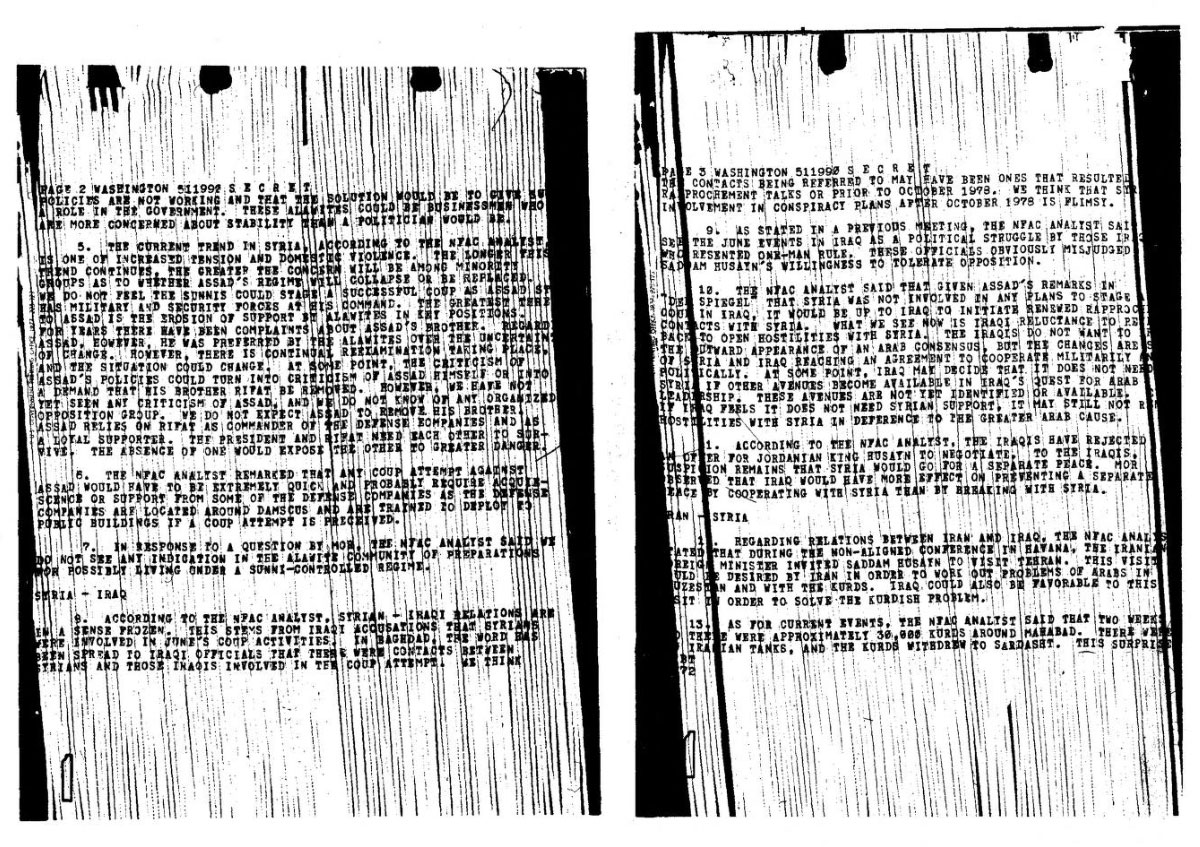

But the shredded paper, although difficult, can be assembled. This is what the Iranian revolutionaries did, and as a result, they released a huge collection of classified documents called “Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den.”

There is nothing particularly interesting for the reader in these documents. They mainly consist of letters and instructions for spies and double agents, which require a deep understanding of espionage to comprehend.

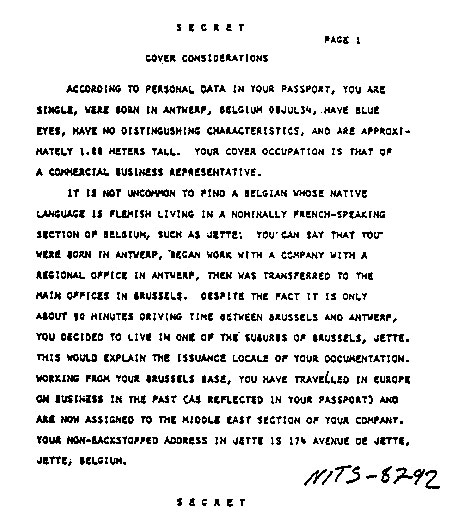

Well, for example, here are secret letters with instructions for spies.

The first letter is a background, a fictional legend for the CIA agent named Thomas L. Ahern, who is operating in Iran under the guise of a Belgian citizen. The letter explains that he was born in Antwerp and his purpose of coming to Iran is for business. The agent speaks French poorly, so his primary language is Flemish. According to the legend, the agent lives in the suburbs of Brussels but works in Antwerp.

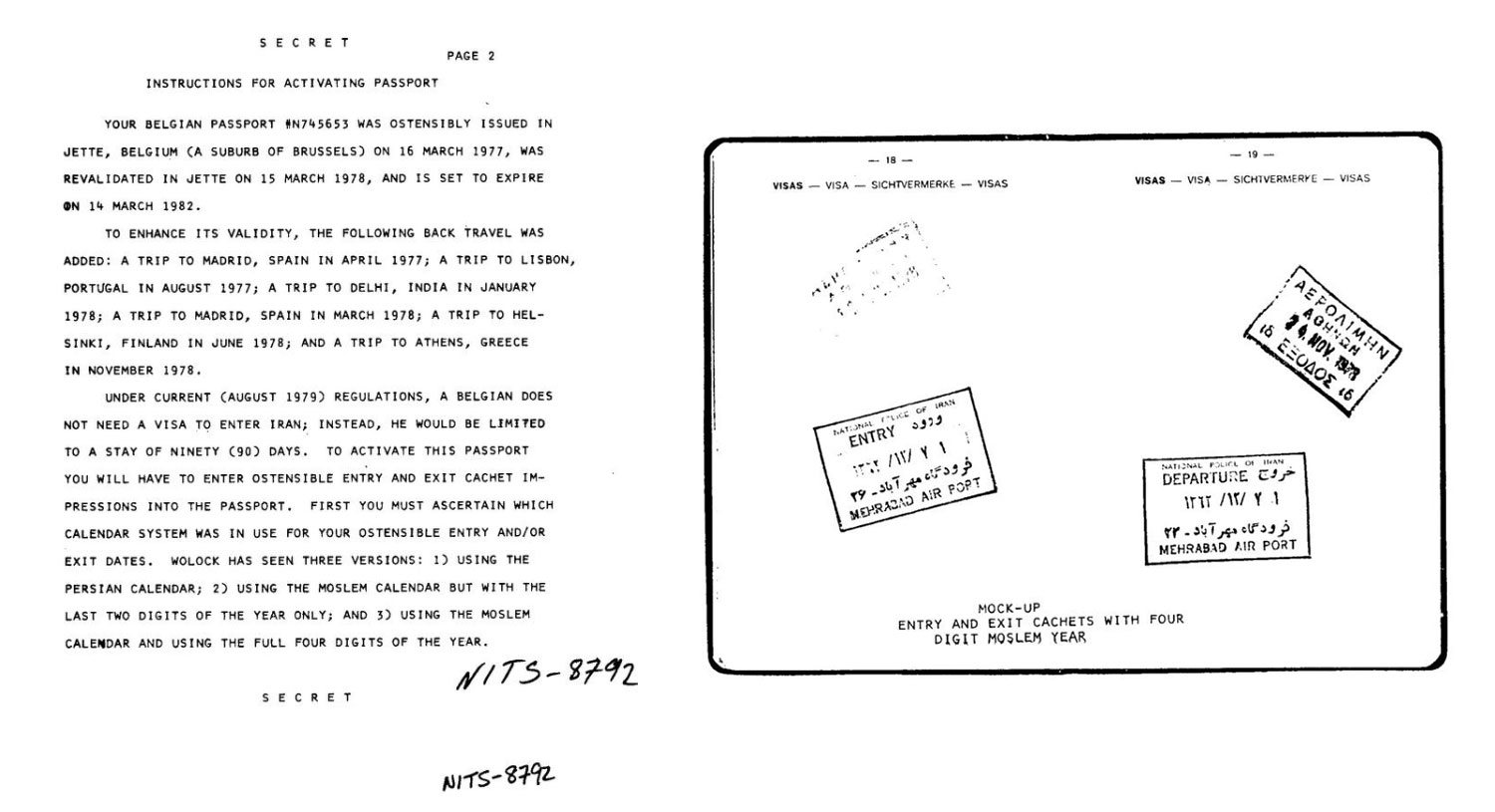

The second letter is an instruction on passport usage. From it, we can learn that a foreign passport has been fabricated for the agent, with fictitious visas and stamps added to make it appear authentic. Scans of the passport are attached.

The most interesting part: in the Tehran embassy, they found a bunch of compromising material on the USSR. The letters discuss double agents such as Alexander Ogorodnik, Anatoly Filatov, and others. They all worked for US intelligence. Ogorodnik was arrested by the KGB in 1977; during the interrogation, he pulled out a pen, bit off the cap, and promptly kicked the bucket. Filatov was sentenced to 15 years in prison. In principle, these stories are known, and you can read about them in many places. They only fail to mention where the USSR got so many spies from.

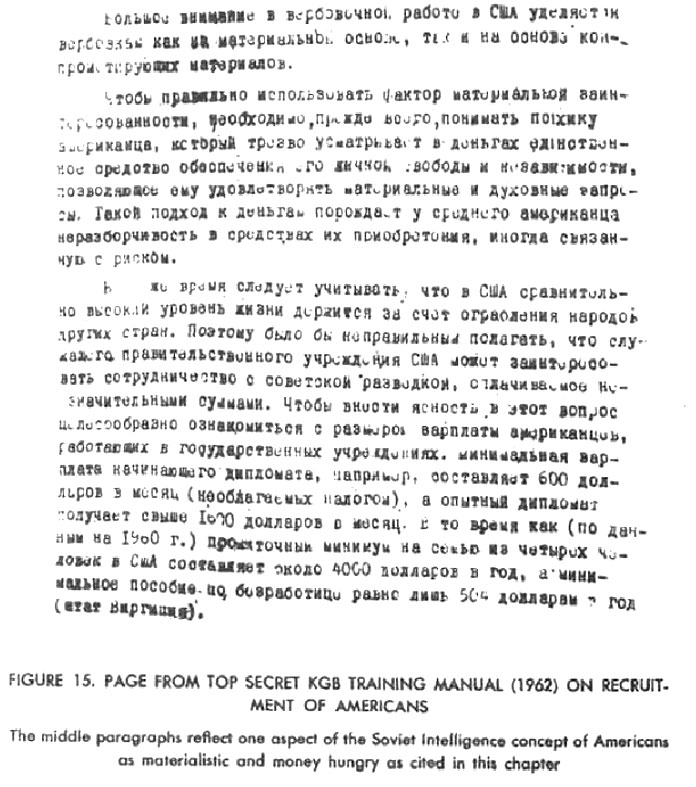

And here’s what the Tehran documents state. The highlight of the Soviet part of the documents is a small excerpt in Russian, which makes it clear that the communists fervently believed that Americans cared only about money. Therefore, they paid their spies with ideology and Marxism. The whole country later paid the price for it.

⁂

Let’s take one last look at Tehran. Even under conditions of global isolation, the city is gradually transforming into a megacity. Tehran has a convenient metro system with 120 stations that runs through the entire city.

Surface transportation is also quite convenient — old buses run everywhere, and modern bus stops are appearing on the streets.

Traffic on the highways is fast and abundant. Modest but clean residential neighborhoods pass by in the taxi window. In the distance, the towering Milad Tower and the first modest skyscrapers shimmer. The walls of buildings are adorned with the works of street artists.

Iranian youth secretly venture out to rave parties in the desert, watch banned movies at home, and hang out near the city theater building.

Tehran has developed to approximately the level of CIS countries despite forty years of sanctions and an utterly incompetent government. What will happen if Iran sheds its despised regime and becomes a participant in the global economy?