Yazd

There were still 3,000 years until the beginning of our era, and Persian media had already written about Yazd.

For genuine beauty and true Persian architecture, one should visit Yazd. After Isfahan, where everything worth seeing has been artificially brought together in one square, Yazd appears as a natural creation.

The architecture of Yazd has been preserved since the 12th century. The main mosque in the city was built in 1324. Since then, it has undoubtedly undergone many changes and additions, but the fact remains: giant minarets, the tallest in Iran, have stood in the city center for almost 700 years.

By the way, this style is called “Azeri,” which refers to Azerbaijani architectural style. As the reader may recall, Azerbaijan historically was part of Iran.

Opposite the mosque, a stereotypical Persian dome looms above the city skyline, approximately from the same period of construction.

Why did people start building domes in the first place? Well, firstly, it’s beautiful. Secondly, it’s a challenge: try putting a round dome on a square mosque.

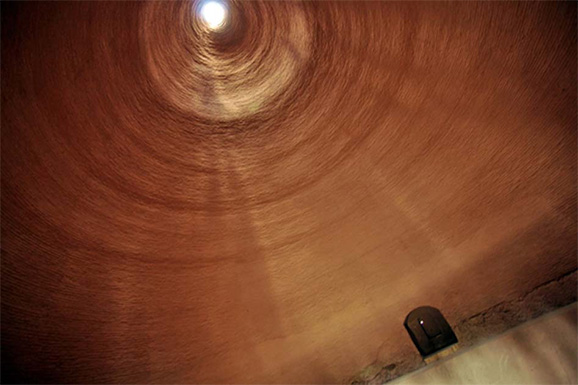

In general, the dome resembles the celestial vault in shape. In other words, a dome in architecture is an attempt by humans to create their own little sky overhead, but with coolness and without rain. That’s why domes are particularly popular in religious structures. Having one’s own little sky in a temple is especially relevant.

As far as the author knows, domes originally emerged in Persia and then spread to the Middle East and Europe.

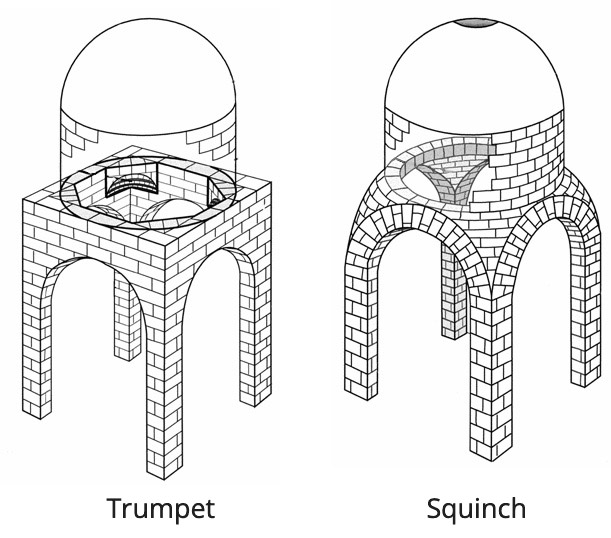

The most challenging aspect of constructing domes is indeed the process of placing a round vault on a square room. If you simply place a round dome on a square base, there will be gaps in the corners. It was in Persia where they first learned to elegantly close these gaps by adding cones in the corners of the square.

Then came the well-known Byzantine dome, from which various variations emerged, including the domes of Russian churches and Roman cathedrals. The key innovation introduced in Byzantium was transferring the domes onto a new type of support system that converges towards the center of the dome, holding it up without the need for any buttresses.

Nowadays, architects refer to the Persian method of dome construction as “trumpet” and the Byzantine method as “squinch.”

Weeeell. Then, even before they learned to place domes on mosques, they used to bury them in the ground — it was easier to close the gaps there — and they were also used for cooling.

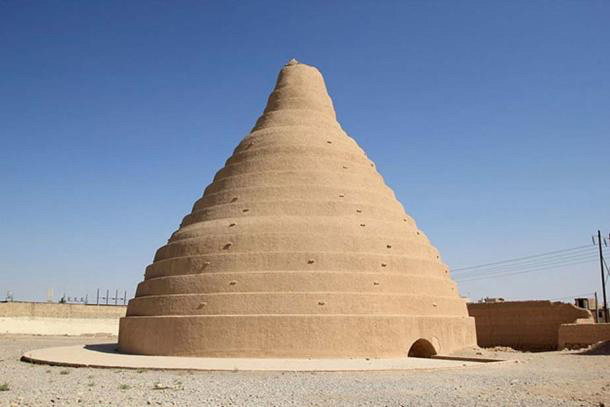

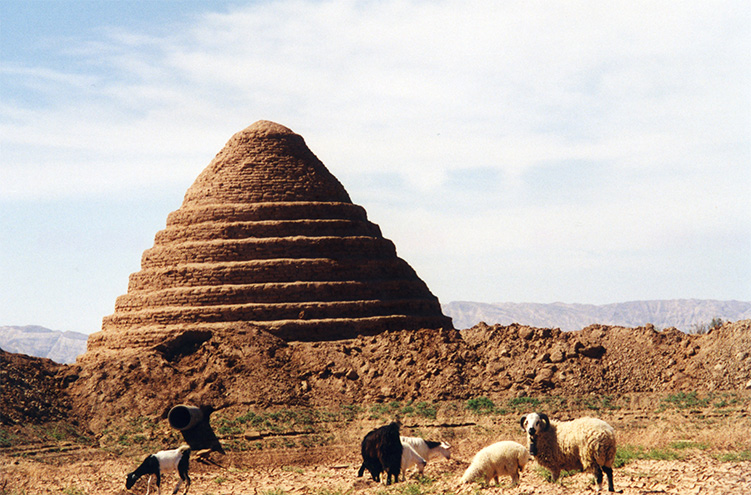

At first, they were simply shapeless structures resembling anthills, which were called “yahchal” in Persian.

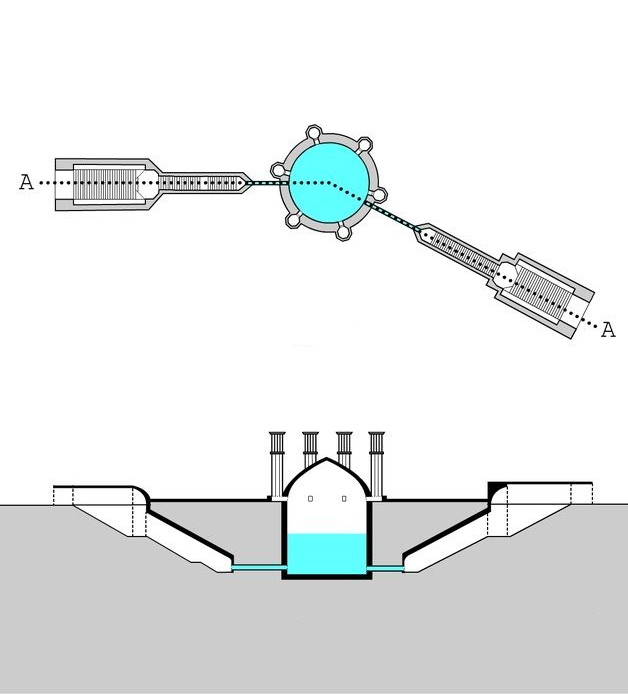

Then the “yahchal” structures were combined with another ancient invention, which seemingly came from Egypt — windcatchers. The result was an incredible construction resembling a mosque with minarets, partially buried in the ground.

Such structures are called “ab-anbar” in Iran, and they serve as Persian refrigerators.

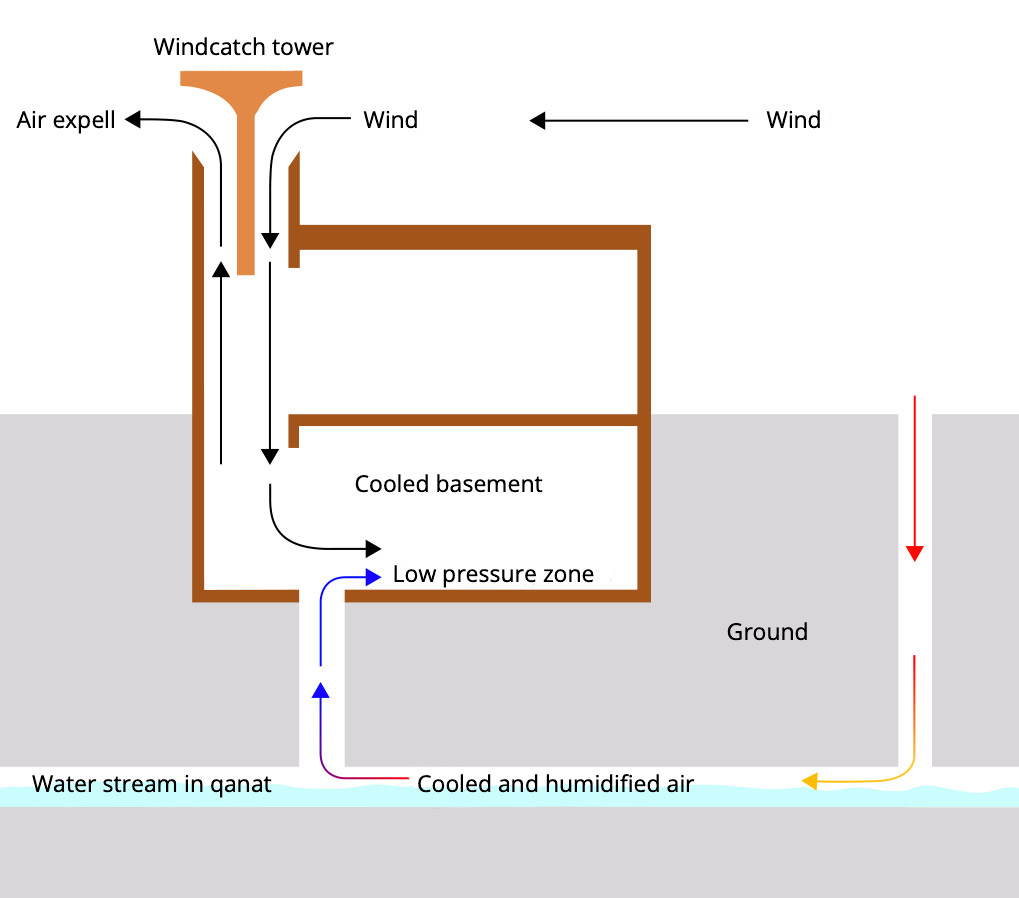

It operates as follows. Underground, in general, is inherently cooler than the surface. Therefore, it is possible to store food and water in underground storages.

But where does the water come from? Are they supposed to carry it in a pitcher all the way from the Persian Gulf?

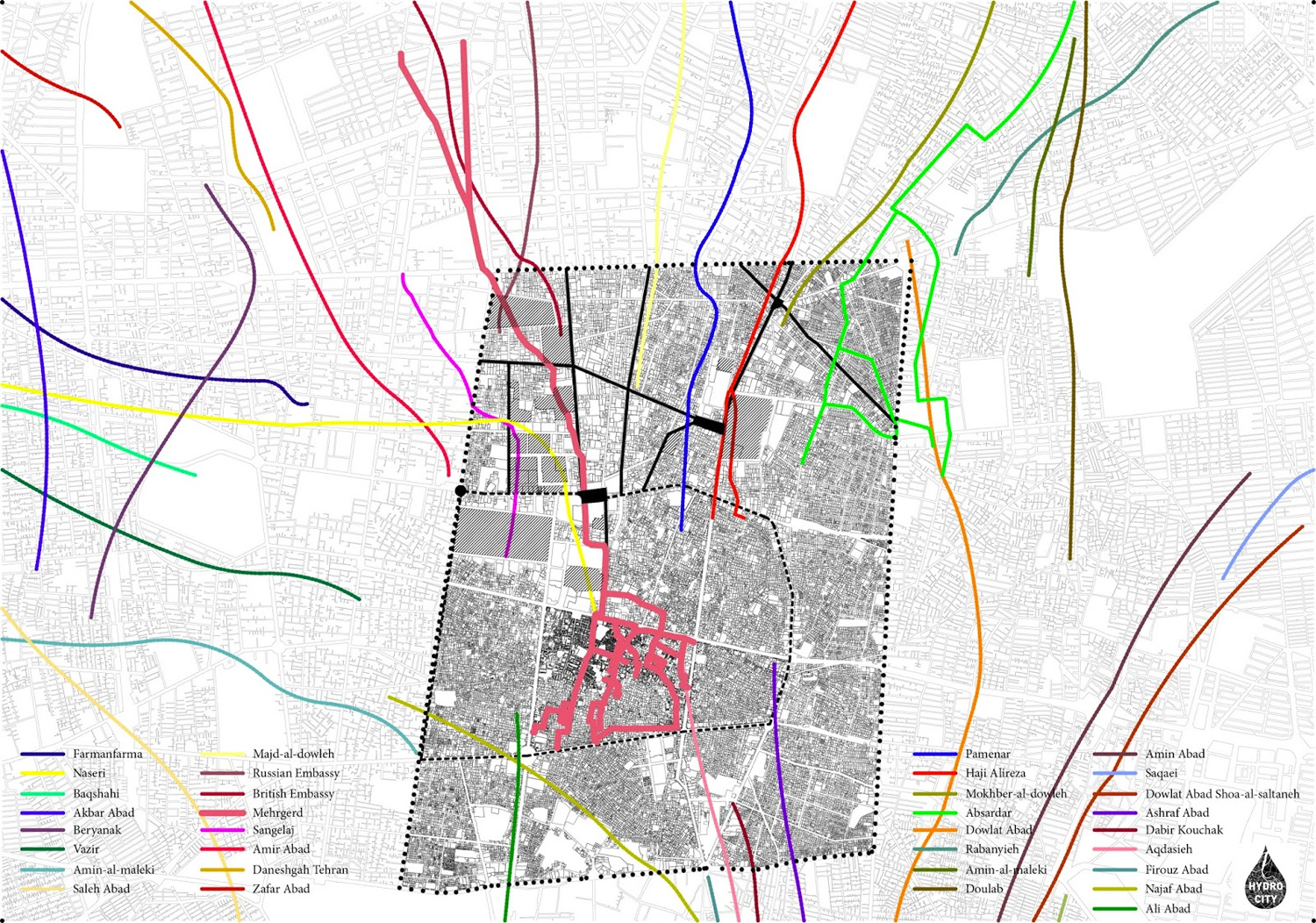

As it turns out, old Iranian cities are extensively interlaced with underground channels that gather water from sources and create a network to serve the entire city.

These channels are called “kahrez” or “qanats.” I couldn’t find a map of the qanats in Yazd, but I did find one for Tehran. Reader, just take a look at this! The water supply network, which is over a thousand years old, envelops the entire Tehran!

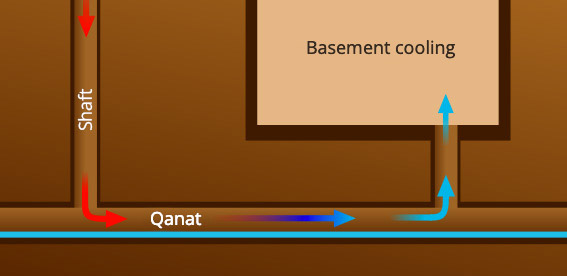

Certainly, Tehran now has modern sewage systems in place, but qanats are still relevant for Yazd. The constant flow of water creates negative pressure. Through a specially dug shaft in the ground, hot air is drawn into the qanat and cooled by the water flow.

It cools down significantly, by 10—15 degrees Celsius. Then the air enters the basements of residential houses, which are all connected to the qanats, and it cools down the entire house.

In conclusion, we have an ancient Persian system of central cooling. By the way, in the Soviet Union, they learned how to centrally heat buildings but never got around to air conditioning.

But for the refrigerator to work even better, windcatch towers are connected to it. It is preferable to have them on all four sides. The top of the wind tower is divided into two parts. On one side, the wind is blown into the wind tower, descends down the tower, and ventilates the room. On the other side, air is expelled due to pressure difference.

In an advanced wind tower, there are not just 2 but 4 or more facets to capture the wind, no matter where it blows from. Additionally, on each facet, there are shutters that can be opened and closed like blinds. The wind tower can be opened on one side and closed on the other, adjusting the gap or completely closing it — full control over the temperature in the house. This was invented a thousand years before the invention of an air conditioner.

Science, bitch!

Going back to it: in the name of this thing called “ab-anbar,” the first word “ab” means “water” in Persian. And this entire monstrous system of water canals was built with one purpose — to store precious water. Later, the Persians developed the idea into an air conditioner.

Yazd has such a well-developed cooling system that it is referred to as the city of wind towers.

Here they are, these little towers. The whole city is dotted with them. It’s not always clear what they belong to and what they cool. They stand in the middle of nothing.

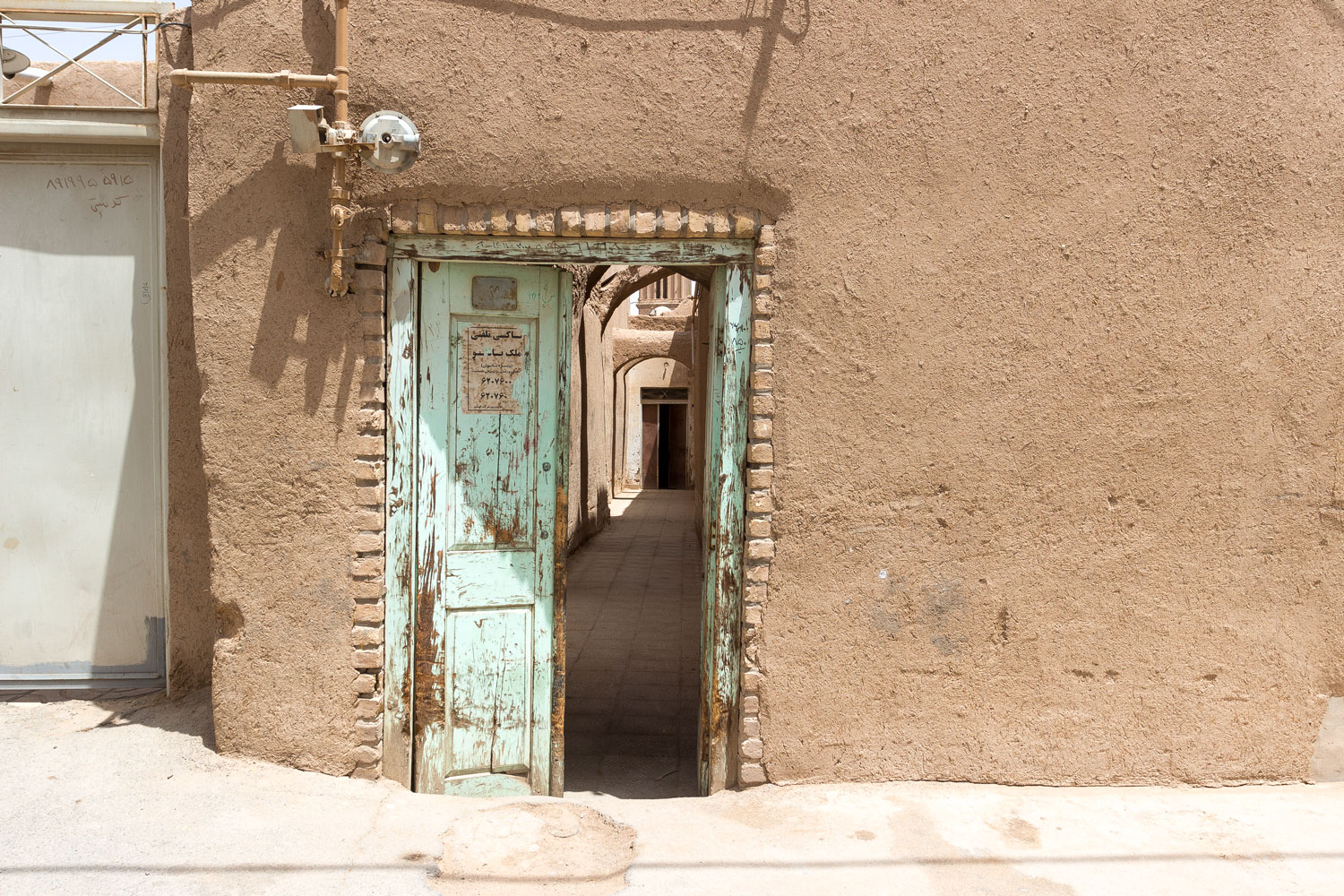

That’s because half of the city lives underground. Look, here’s a completely rundown alley. There’s a sign hanging on a one-story building that says “Silk Road Hotel.” Would you like to stay in such a hotel?

You’re mistaken, because the entire hotel is actually located underground. There is a large space there, with trees, a fountain, several dozen rooms, and two levels.

Or here’s another example. An inconspicuous row of cafes with signs that say “Traditional Cuisine.” You walk by and think that they are some shabby dineries.

You go inside, and there you find something akin to the Sistine Chapel.

At first, it’s unclear how all of this fits here. It seemed like the house was just one story. But the thing is, the domes that are built above the houses are not visible from the street. Moreover, they are slightly sunken into the ground: when you enter, you descend down a staircase. That’s where the five-meter-high ceilings come from.

The dome in the center of the expensive hotel resembles a caravanserai.

The small domes in the hotel courtyard resemble either ladybugs or windmills. The tops of the domes are adorned with colorful glass that tints the sunlight, and underneath them is a restaurant.

And now, having understood the structure of a Persian city, we can move on to the streets.

Yazd is beautiful. The entire old center is built with compressed clay.

It is said that rain can erode clay houses. In the Saudi city of Jeddah, the historical center of Al-Balad was significantly affected by rainfall. Perhaps Iranian houses are held together by dry straw used in the walls.

Sometimes the walls are eroded, and the holes are patched up with bricks.

Other houses are propped up with sticks to prevent them from collapsing onto each other.

Yazd is divine in its decay. Now we know that behind a decaying door, there could be a hidden palace.

You can wander around the old city for days, exploring narrow streets, peeking around corners, and stepping inside doorways.

Yazd is incredible. The gaze is captivated by the textures, patterns, and protrusions on the walls, seeking out rugged recesses and bulges, indentations, abrasions, and roughness.

The sharpness of the cityscape is such that it feels as if someone has enabled anisotropic filtering in one’s mind. The textures of the clay walls, seasoned with straw, are so vivid that one can almost feel them scratching against the surface of the eye.

Yazd is pointless to describe — one needs to come here, touch it, embrace and kiss these walls, lie next to them, and scream out of visual-graphic ecstasy.

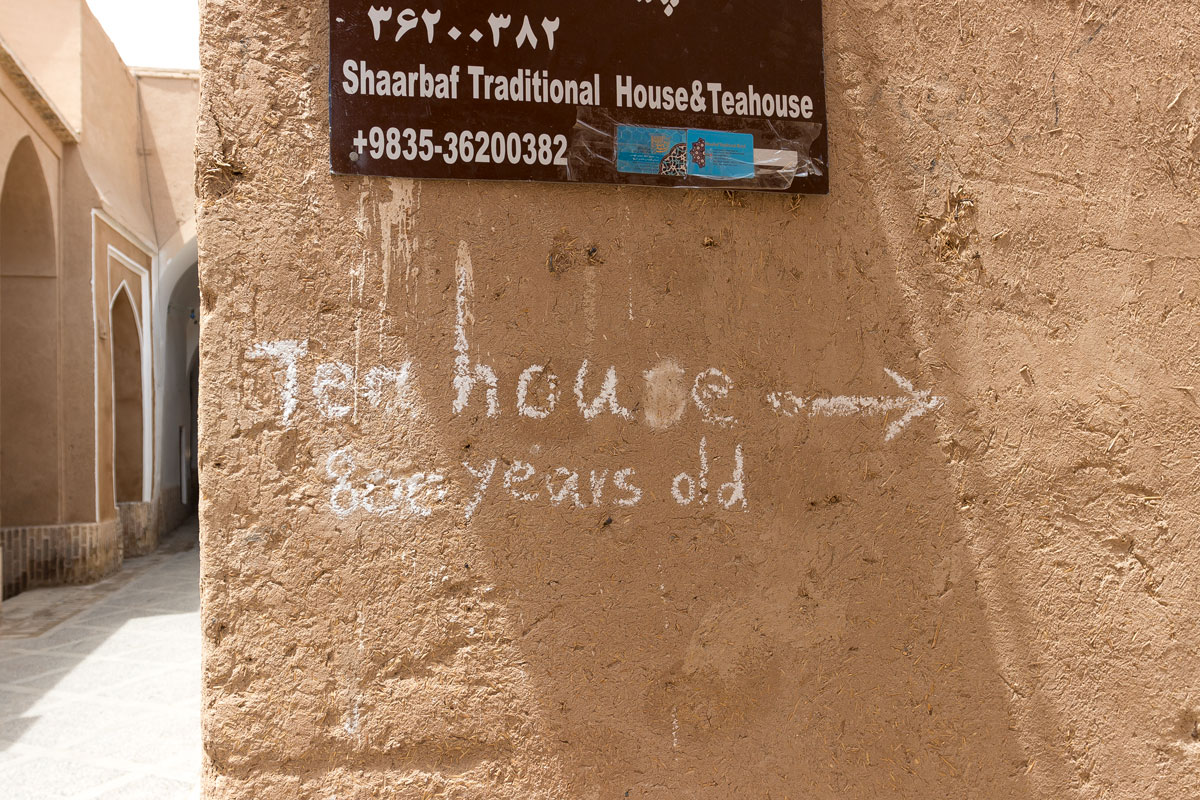

I don’t know how many years these houses have been here. A humble chalk inscription that reads “Teahouse, 800 years” suggests that many.

No matter how much it is, you see, it’s just shocking here. Look further for yourself, I’ll go have some tea.

It was hot in Yazd that day. The sun was blazing at 30 degrees, baking me in the labyrinth of old streets. A carpet merchant, an elderly Persian man, sat in the shade of his stall. His little grandson played at being a grown-up: sometimes digging with a shovel, sometimes sweeping with a broom, and occasionally striking a businesslike pose against the backdrop of magnificent carpets.

In a corner sat an old beverage merchant. I managed to read in Persian letter by letter: “li-mo-na-d.” The merchant quickly understood what was what and called out in the language I knew: “Hey! Friend! Lemonade, very-very! Very-very!”

Apart from the old Iranian man with his ten copper pots filled with strange liquids, there was no source of water within a kilometer radius. We both knew that. The lemonade sheikh began to open the pots one by one and scoop out with a tablespoon into a plastic cup some indiscernible slime, constantly repeating: “Lemonade, very-very! Very-very!”

After mixing seven ingredients, the Iranian handed me a glass of his cocktail, and that’s when I understood where the goods from Eastern markets disappear to. Oh Allah, on that day, the sheikh mixed the entire Isfahan bazaar in the lemonade: from lemon and passion fruit to sweet cotton candy and beads.

The labyrinths of old Yazd can captivate for several days. Once the underground level of the city is explored, attention turns to the above-ground level—the rooftops of the city are interconnected, and it is said that even tours are conducted on them.

Beyond the boundaries of the old neighborhoods, Yazd strives to be modern. Trendy cafes, boutiques, restaurants, and banks are opening up.

The main street of the city is clean, with trees and decent streetlights, parking restrictions, and tactile paving for the visually impaired.

Modernity and cleanliness, like in other cities of Iran, are quite fleeting. Half a kilometer away, the city transforms into a battlefield, tourists vanish, and the sky is covered with clouds. It doesn’t seem dangerous here, but there is little pleasure. By the way, this is on the way to the oldest Zoroastrian temple, which stands away from the city center.

There is nothing worth seeing there, though.

But what’s best of all is to climb onto the roof of an old café, one with a dome, after a hot day spent in the clay Persian streets. Here, a soft divan is already laid out, and the waiter, bowing their head, carries tea up the narrow steep staircase.

Iranian tea is made with mint and served with honey. However, it’s not the viscous mass of honey as we are accustomed to. It is some kind of honey crystals that resemble mountain minerals or precious stones in shape. It grows similar to beryl or aquamarine. The crystallized honey is placed on a wooden stick that is dipped into the tea.

They serve desserts: baklava, cookies, chocolate. After the daytime heat outside, it’s cool, and now you seek refuge not in cold lemonade but in hot tea.

You sit on the rooftop of an old Iranian café and look around. The dome of a thousand-year-old mosque is illuminated with sapphire-blue light. While it’s not quite night yet, the silhouettes of black dresses rush along the streets below, resembling ghosts. The divan is soft, adorned with carpets and cushions; antique lanterns with energy-saving bulbs sway like anchors. You drink this mint tea with honey crystals — a tea that is ordinary in taste, really.

And suddenly, it’s no longer about the tea. You’re not just drinking tea. Into your cup pours the essence of an Iranian evening, its air and lights. You’re not just drinking tea — you’re drinking clay Persian rooftops with domes, drinking illuminated minarets, drinking the mosque, drinking lanterns swaying in the wind, drinking the mazes of old streets blended with cardamom and zaratustra, with the taste of intricately woven mosaic, with the sweet aroma of straw, clay, and sand.

Everything became beautiful on the old Iranian roof. I wanted to share magical tea with someone, but in the night Iran, there was only me and the waiter.