Sarajevo

The roads between Dubrovnik and Sarajevo only appear as straight segments on the map; in reality, the roads in these areas constantly loop and intertwine into a complex tangle, leading through mountains with serpentine routes.

Bosnia is wonderful.

Even on the approach to Sarajevo, you realize that there is no trace left of Europe. The landscapes and city silhouettes with prominent minarets rather resemble Palestine, only gloomy and cold.

Bosnia is related to Palestine not only in terms of landscapes but also in the state of the country, and the history of the conflict has something in common. Bosnia suffered more than any other republic during the dissolution of former Yugoslavia. Its economy is still in a deep crisis, and many cities, including the capital, have yet to recover from the war.

When Yugoslavia began to disintegrate, Slovenia was the first to break away from the crumbling empire. Being the most economically developed and geographically close to the center of Europe, the republic managed to secede quickly and bloodlessly. The secession process was more difficult for Croatia: the country was involved in a four-year war and suffered damage, including to Dubrovnik.

As for Bosnia, the conflict in this country escalated into a real catastrophe and nearly tore it apart.

⁂

More than half of Bosnia’s population are Muslims. The country has a large number of mosques, all of which have a down-to-earth Balkan charm.

The first impression when you arrive in Sarajevo is as if you’ve arrived in Jerusalem. Similar streams of houses flow somewhere into the mountains.

Women often wear hijab, the city center features bazaar architecture, and even the tiles on the sidewalks resemble those in Palestine.

Of course, like Arabs, Bosnians love to sit on small chairs, drink tea, and smoke a hookah.

Sarajevo is often referred to as the European Jerusalem. Here, you can find a mosque, an Orthodox church, a Catholic cathedral, and a synagogue in close proximity.

With a slight touch of Eastern charm, at first glance, Sarajevo doesn’t differ much from Zagreb.

In some sense, it is even worse here. Much poorer.

Everything is abandoned, even architectural monuments.

A typical Sarajevo alley is polluted with graffiti, cluttered with cars, and filled with construction debris.

Bosnia appears to be the poorest country in the Balkans.

Amidst all this misery, the only modern skyscraper towers over the city — the Avaz news agency tower. It immediately becomes clear who holds the power in the country.

From the tower, there is a beautiful view of Sarajevo.

The view from Sarajevo to the tower is not very beatiful.

It’s not immediately clear what to expect from a city whose central train station still displays a poster for the “1984 Olympics” in 2016. Thirty-two years have passed!

But Sarajevo is a beautiful and astonishing city. In reality, it is simply an undiluted cultural concentrate mixed with the remnants of military artifacts.

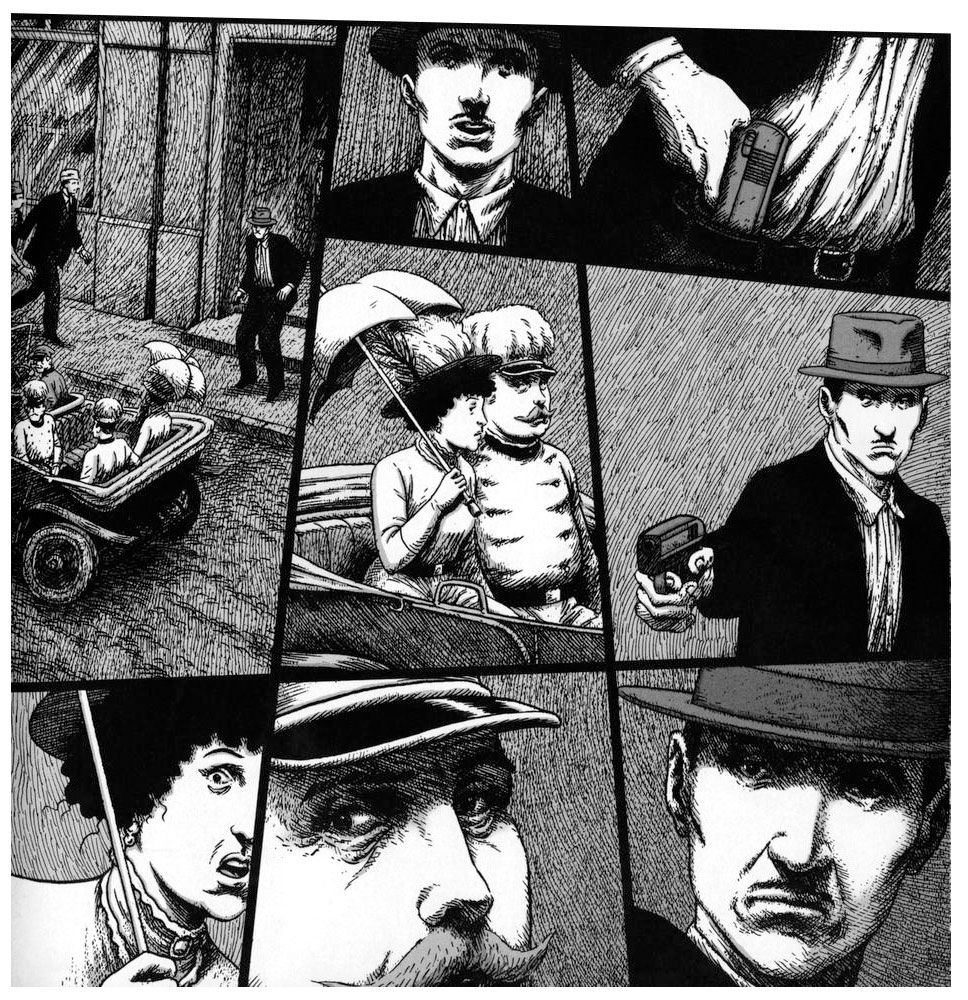

The most famous place in the city is the so-called “Latin Bridge.”

It was here, in 1914, that Gavrilo Princip assassinated Franz Ferdinand. The First World War began from this inconspicuous bridge in Sarajevo.

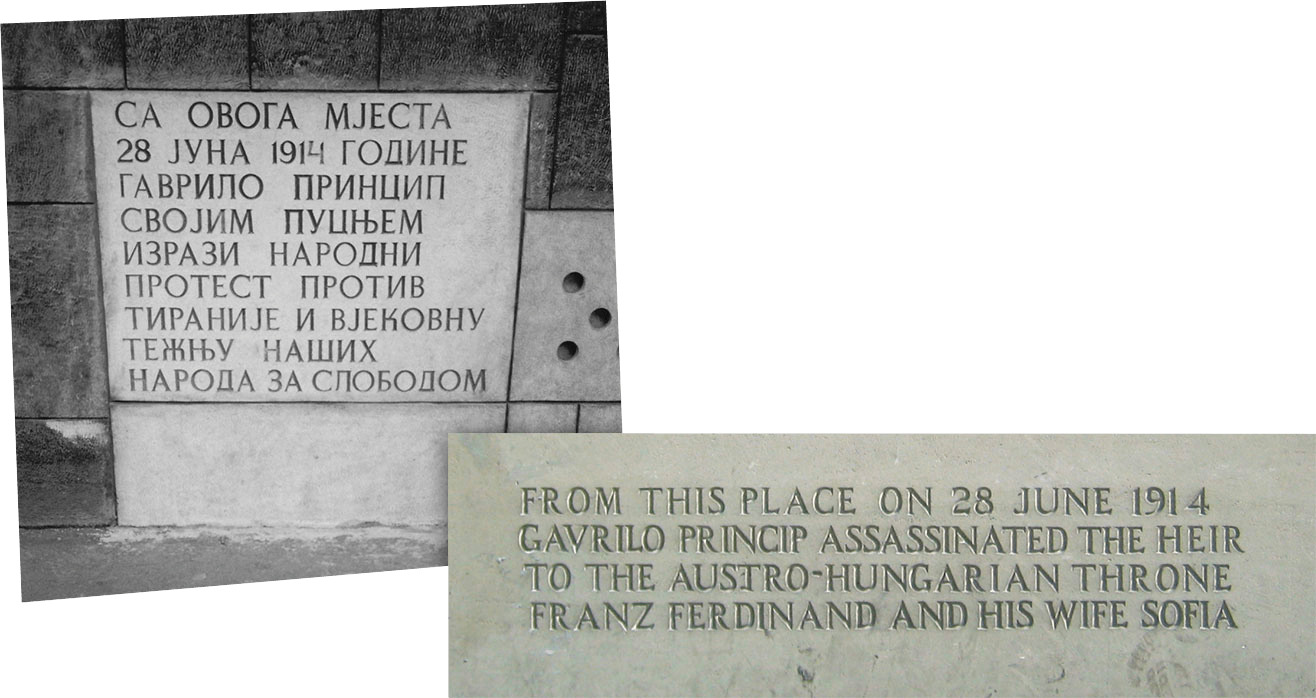

It is interesting how the perception of Gavrilo Princip has changed over time. The war led to the formation of Yugoslavia, and before its dissolution, there was a plaque on the bridge praising Gavrilo for “expressing with his shot the people’s protest against tyranny.” After the breakup, the plaque was replaced with a neutral one: “Franz Ferdinand was killed here.”

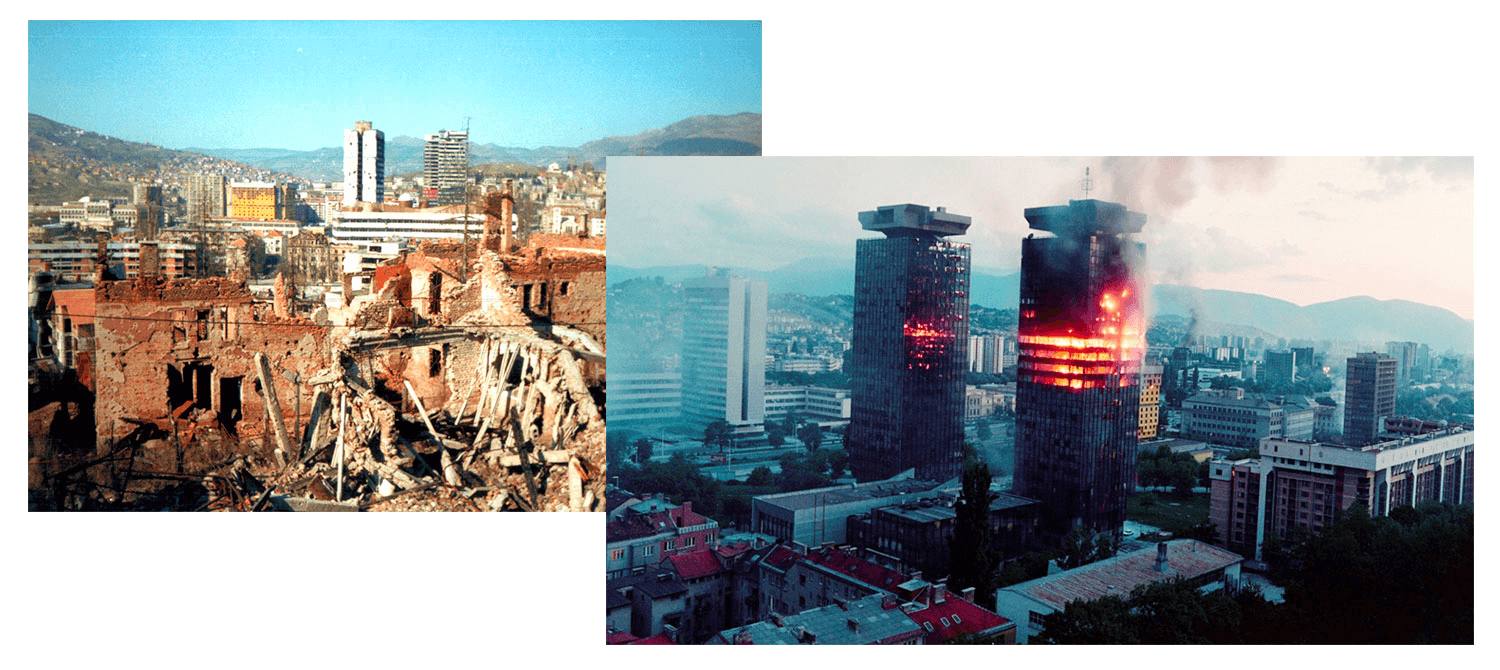

Such a historical place elevates the already dense atmosphere of Sarajevo to unimaginable heights. The consequences of the 1992-1995 war begin to be perceived independently of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, evoking direct associations with the First World War.

There is a lingering thought in the air that the war in Sarajevo has not ceased for over a hundred years. It’s not surprising, considering that even not all historical buildings in the city center have been rid of shrapnel scars.

What can be said about ordinary residential houses? Traces of war will haunt you wherever you find yourself in Sarajevo.

The further from the center, the more destruction there is. In some areas, there are practically holes on every residential house.

Some houses were blown to pieces, leaving only ruins. There is no one to clean them up, so they stand in the middle of the street, surrounded only by a fence with barbed wire.

Among these ruins, there are plenty of stray dogs that gather in packs. Author wanted to explore the ruins more closely — and had to almost run away.

Across the street are the bullet-ridden panel buildings of monstrous architecture and paintwork that survived the war. Somewhere on the facade, there are traces of shrapnel, and in some places, entire floors were hit by projectiles and patched up with bricks.

But the most significant destruction is in areas close to the so-called Eastern Sarajevo. The Bosnian War divided the city into two parts, creating a neighboring entity called “Republika Srpska” as an appendix to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Later, the unrecognized state became part of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a republic with broad autonomy, and the formal border between them was erased. However, the actual border remained — the former frontline is felt several kilometers away.

The houses here are shattered and it is unclear when they will be repaired.

The asphalt hasn’t been changed since the time of the war. Let’s remind the reader that the war ended in 1996. Twenty years have passed, and there are still traces of projectiles on the asphalt.

Traces of shrapnel on lampposts.

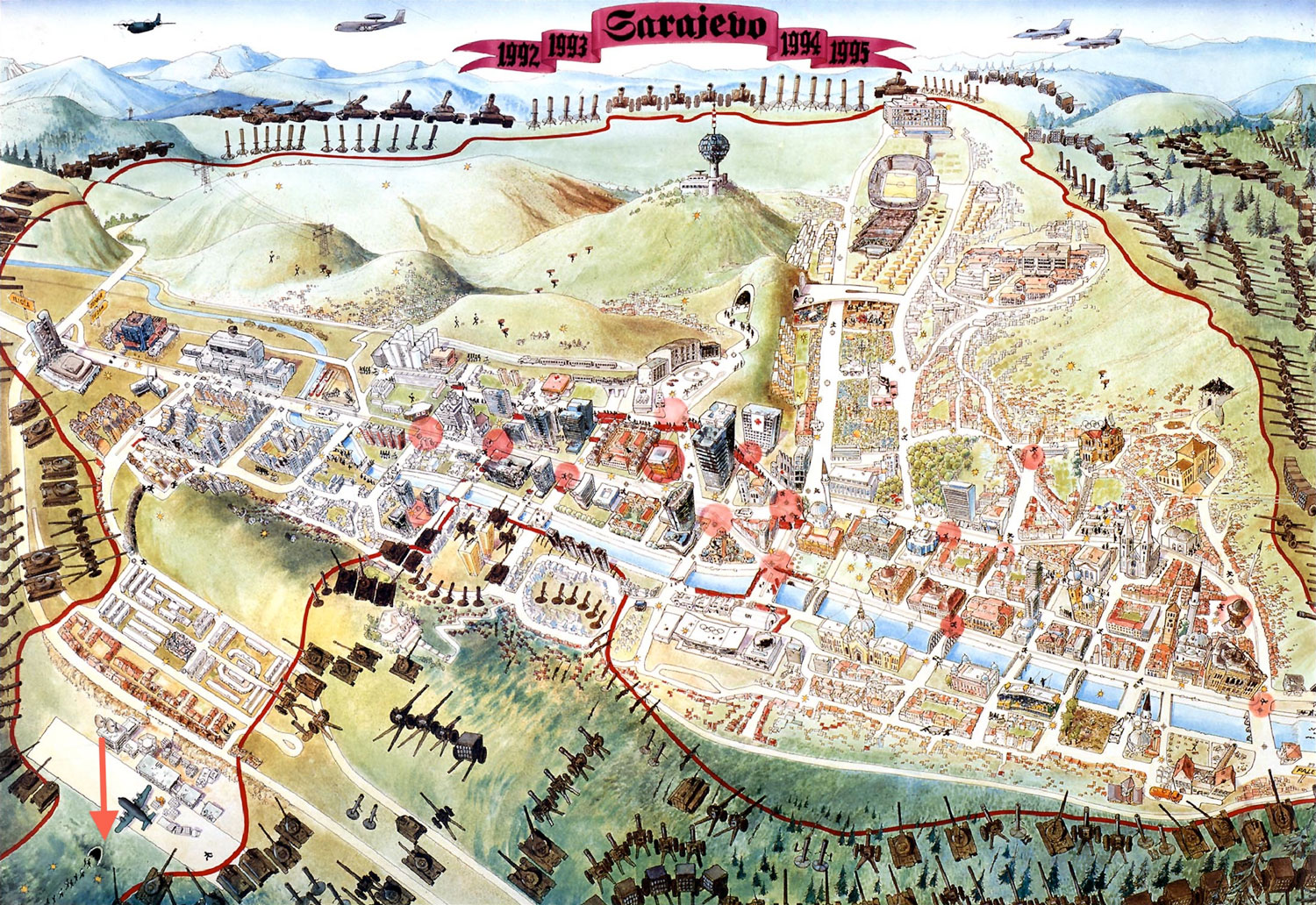

What triggered the war, or more precisely, the main episode of the war — the four-year siege of Sarajevo?

Just as the First World War started with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the Bosnian War began with a “retaliation” that came many years later — in the center of Sarajevo, some Muslims killed a certain Serb during a wedding. It was likely a personal dispute that escalated and ended up affecting the entire country.

At that time, a referendum on secession from the disintegrating Yugoslavia was taking place in Bosnia, which the Serbs — comprising one-third of the population — dismissed with contempt. The inevitable outcome was the declaration of independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina a couple of days later.

One month later, Europe recognized the independence of Bosnia, and on the same day, the Yugoslav army and Bosnian Serbs began encircling Sarajevo. Under the pretext of protecting the Serbian population from destruction by radicalized Muslims, of course.

Then a full-scale blockade began, which lasted for almost four years and surpassed in scale anything seen in Europe since World War II.

For four years, the city was completely deprived of a normal life. Everything was as expected during a siege, nothing out of the ordinary: lack of electricity, hot and cold water, shortage of food, hunger, lack of communication, blockade of all transportation and the airport, as well as regular and intense bombardment of the city.

In short, another senseless and merciless war.

What did NATO do all this time? The same as always — they threatened to deploy troops against the Serbs. Full-scale intervention began only in 1994 when the city was already heavily devastated, with thousands of civilian casualties in Sarajevo alone, not to mention the massacre in Srebrenica and other towns.

The inaction of NATO and the UN was such a slap in the face for the Bosnians that it gave rise to a multitude of parodies and slogans, “United Nothing” being the most well-known.

Shortly before NATO’s intervention, the Bosnian army managed to dig an almost one-kilometer-long tunnel under the airport, connecting the two severed parts of the city. Through this tunnel, several thousand soldiers passed daily and supplied the isolated areas of the city with humanitarian aid.

The tunnel emerged on the outskirts of the city, into rural areas. The ruins of houses remain here to this day.

Perfect invisibility of the exit saved the tunnel from being detected — it was located in one of the rural yards.

And here you realize that the most amazing thing in Sarajevo is the one hundred percent preservation of time. Just like that Olympic poster hanging at the train station since 1984, the tunnel hasn’t disappeared since the war. Its main length was buried, and the remaining part was turned into a military museum.

Anyone can descend and feel like a Sarajevo refugee.

Warheads are hanging. The guide tells that when he was a child, he used to run around the city with friends, collecting remnants of shells and extracting bullets from walls.

The children in Sarajevo had a happy childhood. Thank God it’s over.

Although Republika Srpska is now part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Sarajevo is no longer divided in half, the eastern part of the city — just like the eastern part of Jerusalem — lives a somewhat separate life.

Here they commemorate the 20th anniversary of the departure of Serbs.

The inscriptions are written in Cyrillic script.

And in retaliation for removing the plaque from the Latin Bridge, they unveil monuments in “their” part of the city to the despicable troublemaker, the assassin Gavrilo Princip.

Let them open it. The state of Bosnia, 20 years after the war, is as if the war is still ongoing here. Bosnians probably complain that Serbia is to blame for everything? Undoubtedly, Serbia played its role, but it was played out 20 years ago.

The issue is not solely about post-war destruction but widespread corruption. Even the former president of Bosnia and Herzegovina was arrested for granting amensties in exchange for bribes. What can we say? Even after the most devastating war, a country can be rebuilt in 20 years. This is demonstrated by examples such as Israel, Germany, and even the troubled USSR. But Bosnia is not an example of that.

The story about the consequences of the Balkan Wars does not end with Sarajevo. Someday we will reach the other two hotspots of the conflict — Kosovo and the culprit of the events — Belgrade.

Meanwhile, we are leaving Bosnia, with the unhealed scars of destruction from twenty years ago remaining in our memory. The beautiful European Jerusalem, underground tunnels, bullet traces, and the spiraling skyscraper Azala, enveloped in leaden clouds resembling a menacing citadel from a computer game.