Barcelona.

Part Two. Gaudí

Good day, my dear readers. Today I will tell you about the great architect Antoni Gaudí and his legacy that he left in Barcelona.

You will find an amazing story about the incredible Sagrada Familia Cathedral, the wonderful Park Güell with its whimsical houses, and the very beautiful buildings in the center of Barcelona, which were built by the great architect.

Oh my, what I get myself into.

⁂

What can I do? In Barcelona, it’s impossible to come and not be amazed by Gaudí. Because here everything is Gaudí. The main cathedral, the main park, the coolest houses in the city, interiors and furniture, street lamps: one guy — Gaudí — made all of Barcelona.

In general, what is Barcelona at the turn of the century? It is an immensely rich city that, along with Catalonia, joined Spain and has been striving for independence for 30 years now.

In order to achieve independence, civilized countries do not engage in civil wars, destroying half of the cities. Good countries begin with cultural independence — they start to develop economically, speak their own language, paint, design, sculpt, mold, and build in their own way. All this is necessary in order to truly differentiate themselves from the administrative center and later say, “look, we are different.” That’s when the national movement gains a strong foundation and leads to success (actually no).

So, at the turn of the century, wealthy Catalan patrons began pouring tons of money into the arts, and it turned out that most of the money flowed into architecture — the Catalans wanted to catch up with and surpass London and Paris. And they also needed somewhere to live.

Such a wealthy uncle named Güell was lucky to encounter Gaudí, and he commissioned him to build an entire park. After that, orders poured in for the architect at such a speed that he dramatically raised prices and adopted the slogan “Slow. Expensive. Fucking good.”

Of course, Gaudí was not the only one working in Barcelona at that time. The whole of Europe was fascinated by Art Nouveau, and at least three more Barcelona architects were building in this style.

And one day, they all intersected on a small stretch of one of the main streets of the city — Passeig de Gràcia. Each of them sold their own little house right in a row. As a result, it turned into such a wild mishmash of Art Nouveau that this place began to be called the “Block of Discord.” In the sense of the discordance of styles.

The Quarter of Discord

All the houses were residential, initially built for wealthy families, which is why they are named as such: “The House of Someone-There.”

The first one is the Morera House. The architect is Lluís Domènech i Montaner. It’s quite a decent house with complex forms that could easily pass as one of the best in Riga or elsewhere.

To the right of it is the Mulleras House by architect Enric Sagnier. Well, it’s noticeably simpler. Sagnier has more interesting works in Barcelona.

Next comes the third one — the Amatller House, designed by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, a prolific architect who built two dozen houses in Barcelona.

This work is truly interesting. The owner of the Amatller House was a confectioner, which is why the house also has a sweet appearance and the texture on the walls resembles a cake.

The stepped gable facade resembles the best houses in Amsterdam, but with a Catalan motif of its own.

The Gothic balconies with a tremendous amount of elements referencing biblical stories, spiral twisted columns, Latin inscriptions, and a pattern of the letter “A” — the name of the house’s owner, mixed with reliefs of flowers, children, and lions — the Amatller House could have been the coolest architectural monument in Barcelona, if not for one “but.”

And all the architects in Barcelona always had one “but” — Gaudí.

Gaudí came and showed all the architects their place. His architecture is something else. It is transcendent, unlike anything else, taken to the absurd and with a vision of Modernism that is otherworldly and unreal in its forms.

Balconies in the Gothic style, you say? Or what’s there? Smooth forms, spiral columns, semicircular facades? Hold my beer.

Whut? Texture resembling a cake? Unusual facade with a rotunda? All of this looks outdated compared to Gaudí.

Gaudí’s architecture doesn’t just play with form and incorporate natural elements into the facade. It is nature itself. In his buildings, there are no straight lines at all. The columns of balconies are not simply spiraled; they resemble the joints of bones. The roof and walls are not covered with tiles or textured; they are clad in a stone skin resembling dragon scales.

The entire Casa Batlló is like some unknown creature embodied in stone. It seems to have a mouth in the form of a balcony, and eyes in the form of windows. The two spires could be its whiskers. It has both skin and bones. Perhaps it even experiences emotions and feels something. Maybe Gaudí didn’t just build houses; he synthesized a new form of life? Not a protein-based one like Frankenstein, but a stone-based one.

Gaudí’s merit also lies in the fact that he didn’t limit himself to the exterior appearance of the building but created incredibly unique interiors, including furniture. If the Casa Batlló looks like a creature resembling a dragon from the outside, then the interior of the house is the stomach of this creature.

Well, Gaudí charged it up.

It’s interesting, how did Gaudí come up with all of this? LSD wasn’t invented back then, and hallucinogenic mushrooms didn’t seem to grow in Barcelona. It seems these were endogenous processes after all.

By the way, Gaudí was a radical believer and a radical Catalan. Not only did he exclusively speak Catalan when conversing with the King of Spain, but he also tailored his Christian faith to his nationalistic views. He reinterpreted the Holy Trinity itself: God the Father remained as God, God the Son became nature, and the Holy Spirit became Catalonia itself.

In general, when it came to constructing the main masterpiece of Barcelona, the Sagrada Familia, there couldn’t have been a better candidate than Gaudí.

Sagrada Familia

The main work of Antoni Gaudí is filled with extraordinary symbolism.

First of all, the temple is designed in the shape of a Latin cross, although with the enormous number of architectural intricacies, this is not immediately evident even from above.

Secondly, there are numerous biblical references in the structure. If we consider the number of facades, there are three. If we look at the number of towers, there are twelve, symbolizing the apostles. Additionally, there are four more towers in the center, representing the four main books of the Gospel, forming a cross shape. In the very center stands the giant tower dedicated to Jesus Christ. Of course, not all of this has been completed yet.

Because, and this is thirdly, the construction of the giant church has been ongoing for 136 years since Gaudí stipulated that it should be built solely on donations. Judging by everything, the Barcelona clergy kept their word and did not divert profits from candle factories into the construction.

That’s actually very little. The Milan Cathedral took 579 years to build, and the Cologne Cathedral took 632 years. However, it does make for a great ballad for tourists.

Continuing reading: Gaudí started construction with the Nativity facade because the Passion facade was turning out to be too frightening, and the residents might have been scared off and halted the construction.

Looking at the Nativity facade — if that’s not too scary, then what is? Well, Catholic cathedrals aren’t exactly a walk in the park: dark, with sharp spires — but here it’s just some kind of gaping mouth dripping with saliva.

But that’s the whole trick of Gaudí’s church. The architectural temple canon is filled with a truckload of symbolism, wrapped in the most advanced modernism of its time. It’s like releasing an iPhone according to Soviet GOST standards for phones and getting a modern, cool device made with medieval standards.

In order for the ingenious plan to work, in addition to everything else, the walls of the church had to be covered with countless biblical narratives. On the facades, there are figures of saints, scenes from the life of Christ, and inscriptions in Latin. On the towers, there are sculptures of apostles, Zodiac signs, and crosses. In various other places, the building is generously adorned with sheaves of wheat and clusters of grapes, symbolizing the socialistic wealth Holy Communion.

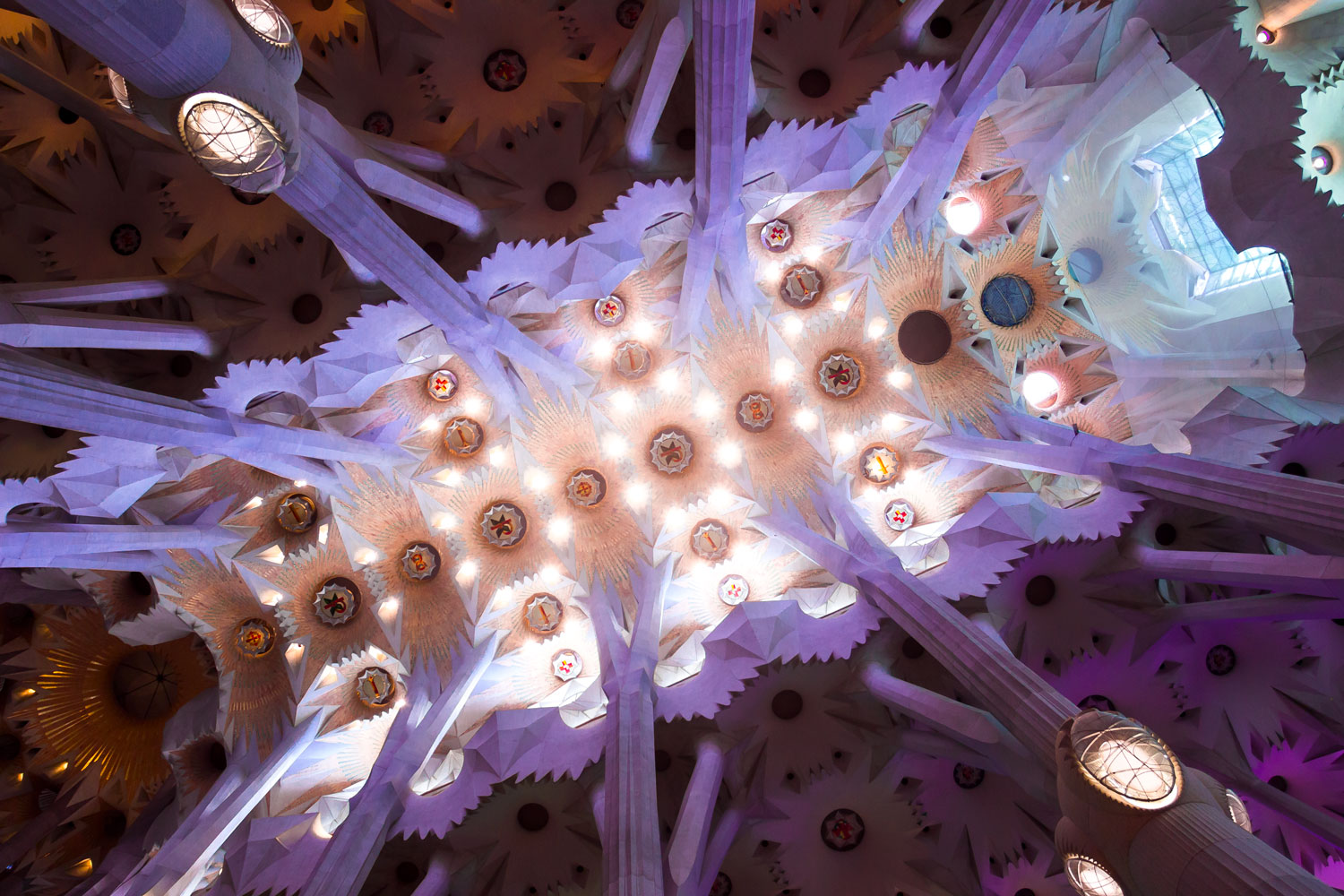

No matter how hard Gaudí tried with the exterior of his temple, the most impressive thing turned out to be the interior, although he barely had time to design it before his death.

Usually, in Catholic cathedrals, the maximum beauty is concentrated in a few stained glass windows. Inside the Sagrada Familia, the stained glass windows run along three walls, and each one is of unique colors, making the play of light in the temple absolutely mind-blowing.

At different times of the day, the interior of the temple is illuminated with different colors. Don’t like the reddish one? Wait an hour.

The columns are designed in the form of trees with branches — a unique solution by Gaudí to balance the load while supporting the vault.

From another angle, the ceiling resembles the abdomen of a crawling insect.

Each “segment” of this abdomen, every little circle in the ceiling, is part of a hyperboloid, a special rotational figure that can be obtained by rotating an ordinary straight line.

All the connections in the internal structure of the temple are based on hyperboloids. That’s why it seems like there are no straight lines in the hall, but in reality, they exist, twisted into a complex geometric shape.

In general, Gaudí brought a lot — and I mean a lot — from nature into architecture. He was influenced by being born far outside the city and spending a lot of time observing due to illness.

Park Güell

It all began with the construction of a park for a Catalan entrepreneur named Guell, who owned textile factories in Catalonia and generously sponsored the arts. It was he who commissioned Gaudí’s first project, and Gaudí built it.

Now the park is still called Park Guell. By the way, you can get a good view of the Sagrada Familia from here.

The park is located on the outskirts of the city, on a hill. That’s why a series of escalators is directly installed through the streets to provide access to it.

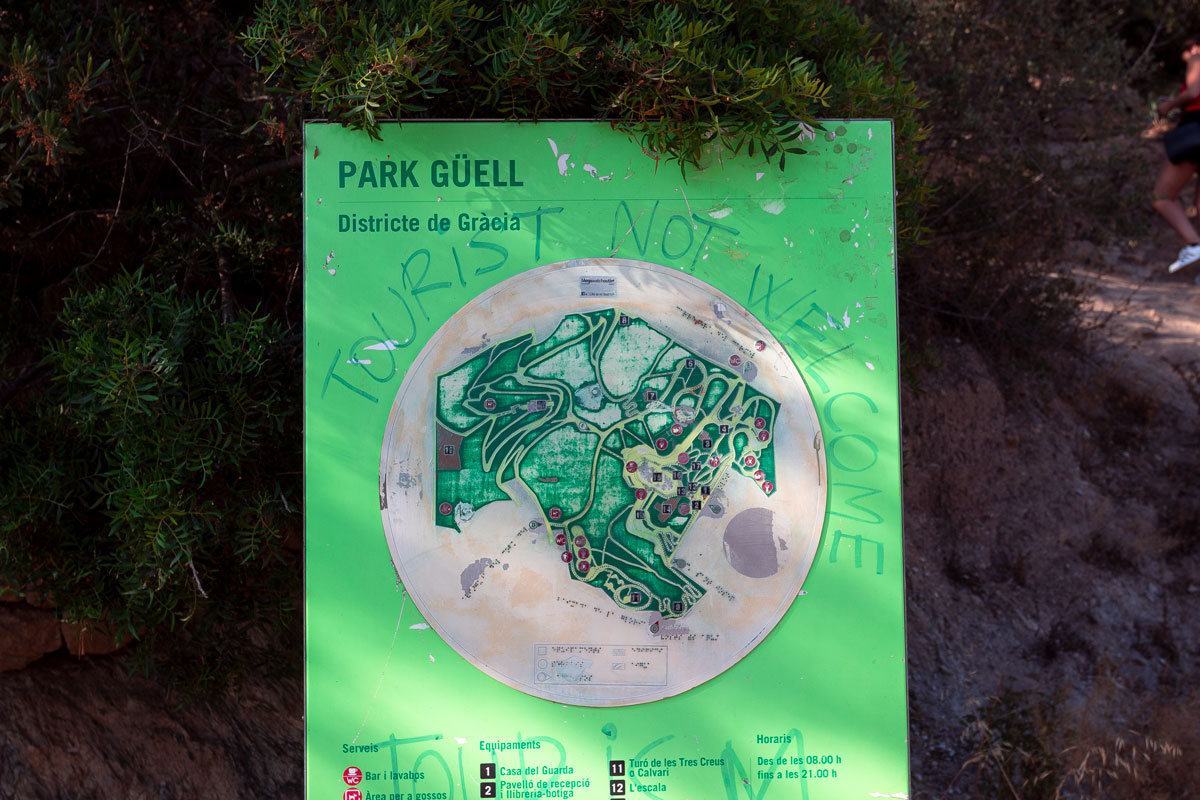

The escalators pass right in front of residential buildings, and throughout the day, there is a constant noise from their operation and the conversations of tourists.

This is a very sad story. The local residents were outrageously angered by such inconsiderate treatment from the authorities in favor of park visitors. That’s why many walls in this neighborhood are covered with insults towards tourists. There is a sign at the park entrance that says, “Tourists not welcome.”

Interestingly, if the escalators were here in the early 20th century when the park was built, it would have been more successful. Because after its construction, it was suddenly discovered that the target audience of the park — the local nobility and intellectuals — were too lazy to travel to the other end of the city and climb up the hill to visit a park.

Oh, yes. The initial idea was to build mansions next to the park and sell them. A brilliant plan. However, the park’s conversion rate turned out to be low, ROI quickly went below zero, and the park was sold off to the government.

After a hundred years, the park’s visitor numbers increased many times over (thanks to the escalators), and now the investments are being recouped (no wonder, with an 8 euro ticket price).

The two sugar houses located at the entrance of Park Guell are the second most recognizable symbol of Barcelona.

And yet, according to the original plan, all that was supposed to be there was the park administration sitting and issuing tickets.

The coolest thing in the park is the long, winding staircase covered in mosaic.

Everyone loves to take photos with it because you can capture the foreground, middle ground, and background — a photographer’s dream. The author waited for half an hour just to capture a portion of the bench without people.

The bench, together with the viewpoint, is supported by the Hall of 100 Columns, which actually has 86 columns.

Overall, well, it’s boring. You can see that it was his first work.

⁂

When it became clear that the park was an economic failure, Gaudí, on the advice of Guell, took it upon himself to buy one of the mansions and lived there until his death. No, he did not die from waking up every day and seeing his park. There were other reasons for his passing.

Despite living a very comfortable life and amassing a considerable fortune, most of which he invested in the Sagrada Familia, towards the end of his life, Gaudí dressed in rags and completely neglected his appearance. It was a clear sign of schizophrenia, by the way.

And one day Gaudí was walking to the church and got hit by a tram. And no one recognized that it was Gaudí because he was dressed in rags and looked like a homeless person. So they took him to a hospital for the poor, and he was identified only a day later, when it was already too late to treat him.

So Gaudí died. You see, how important it is to dress properly. And then in the 21st century, they even wanted to declare him a saint, but something went wrong. However, it is absolutely clear that for Barcelona, Gaudí is a saint. Without any official stuff.