Malaga

Spain is a rare example of a country where it is good in every corner of the land: in the capital, in the village, and in provincial cities. The atmosphere of one of the small cities by our standards, Malaga, is so rich that it seems like this summer air can be cut with a knife.

The balcony parade, launched in Madrid, continues here and reaches a new level.

In Malaga, everything is ten times more interesting: ten times more beautiful, ten times more detailed, ten times more vivid and colorful.

Perhaps this time it is necessary to tell more about the balconies.

There is an interesting fact that is completely impossible to notice without knowing the language: all Spanish city names are perfectly translatable into Arabic. Usually, translating a word into Arabic is roughly the same as typing Russian words using English transliteration: it becomes barely readable. But in Spain, almost all names translate beautifully, letter by letter.

I noticed it by chance, simply because I have traveled a lot in the Middle East. I checked in dictionaries, and indeed: it turned out that Madrid, Malaga, Seville, Granada — all these Spanish names originated from Arabic.

And all because long ago, before the word “Spain” even existed, the Iberian Peninsula was part of the Arab Caliphate. Since the time of the great Muslim conquests, around 10% of words in the Spanish language have been preserved from Arabic, and even the tradition of siesta seems to have been taken from Islamic culture: after the midday prayer, Muslims were prescribed a nap due to the scorching heat.

So, Spanish balconies are also purely Arabic thing.

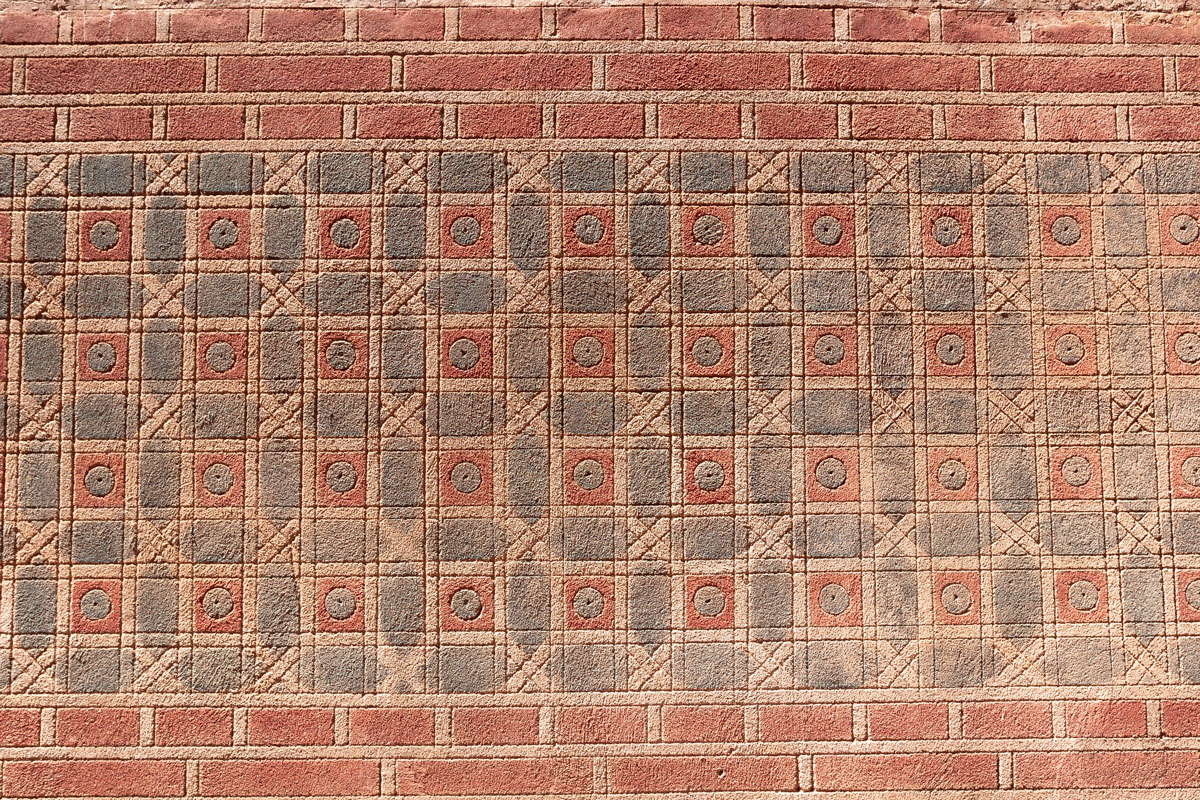

Architecturally, an Arabic balcony is a wooden birdhouse attached to a wall.

Arabs have never known how to build regular housing for people and still don’t, so all their houses are dilapidated cubes made of sand mixed with seashells. The material of old Arab houses is so fragile that a whole house can easily be washed away by heavy rain. Therefore, there could be no talk of any projections on the walls — a balcony on such a projection would collapse instantly.

Therefore, Arabs came up with the idea of cutting out balconies from sticks and fitting them into window openings. I remind the reader of what such balconies look like in the Arabian city of Jeddah.

And now compare it with Spain. The same intricate wooden structure, but placed on a stone projection — the Spaniards have indeed advanced in architecture further than the Arabs.

The balconies of Malaga protrude from sunlit walls, adorned with flowers, and gracefully cascade downwards — and down below, on the streets, under awnings and along coffee tables, it feels so good.

In the heat, it is best to drink hot coffee with cardamom and dates. It’s a pity that they don’t serve dates in Spain, and the coffee options are limited to cappuccino. The Spanish seem to have forgotten this Arabic tradition for some reason.

The delight of Malaga manifests itself in its transformations. As soon as the traveler thoroughly examines every detail of each Malaga balcony, the city instantly presents them with awnings and cafes. Just when you’ve had your fill of them, Malaga offers its microscopic street art.

Then the gaze is captivated by the streets and facades.

In the end, Malaga showcases its squares and open spaces, which are incomparable to those in Madrid.

And on one of these squares sits the most famous resident of Malaga — Pablo Picasso.

Picasso, who worked in the Cubist style, was heavily criticized in the Soviet Union, which is why he remains as unknown in Russia as Spain as a whole. In his most prominent work, “Guernica,” it is unlikely that anyone will discern the Spanish Civil War, which has no relevance to us.

But in Malaga, anyone can discern the endless diversity of a Spanish city, which Picasso absorbed from childhood.

It must be that only after visiting the house, studio, and museum of the artist, Malaga, already bursting at the seams from the internal pressure of its atmosphere, explodes like a massive balloon and scatters into fragments.

A three-dimensional city, like in Picasso’s imagination, disintegrates into two-dimensional elements in your eyes, which gather on the canvas of a photo matrix – details, patterns, textures, and whims of geometric shapes.

The consequences of a big explosion haunt the consciousness until the end of the day, and the city slowly, gradually comes together. Suddenly, you begin to understand the intricate cubism and feel everything that inspired Picasso, not just look, but truly see.

And suddenly it becomes so vividly clear that you cannot be born a second time — to be born in Spain, to absorb Malaga within oneself.