There are no countries in the world more complex than Russia and America. Their history makes your head spin, their size boggles the mind, and you can talk about their politics forever. Trying to write a review of such a country is madness. Trying to write a brief review is double madness.

It so happened that, although the author has visited more than 90 countries around the world, he has truly lived in only these two. It is no surprise, then, that the fate of these two countries is the only one that he genuinely cares about.

On the other hand, writing stories about American cities without an introduction is like starting a biography with the hero’s death. It seems there’s no way around it: I’ll have to take up this mad idea again. Luckily, the author has never been known for soundness of mind.

In the end, the portrait of America did come together. It even turned out to be fairly brief, yet it still took up three chapters. The number of interesting facts in it turned out to be so large that I even had to break my rule about not cluttering up the narrative with footnotes. I suppose this time no one would believe me without them.

And I should warn you upfront. Gentlemen! Passions are running higher than ever before today. But believe me, my reader: whether you’re a Democrat or a Republican, I’m not taking sides in this war. No one’s getting spared.

America. Part One. Yesterday

Democracy the American way — Join or die — Three-fifths of a man — Bleeding Kansas — Depression — The American Empire

Democracy the American way

Unfree countries are all alike; every free country is free in its own way.

Everything was in confusion in Washington’s house. If ten years ago someone had told an American that America is not a democracy, he would have simply laughed in response. Today, such talk doesn’t surprise anyone in the U.S.

“America is not a democracy, has never been one, and was never intended to be.” Today Republicans repeat this daily, leaning on the original meaning of the word “democracy” as it was understood in the 18th century, when the Constitution was written.

In many ways, this is true. The U.S. Constitution does not use the word “democracy” even once because, in the 18th century, it was almost a slur, associated with the mob rule of an unrestrained majority. It was used in the same sense in Ancient Greece. Plato considered democracy to be one of the worst forms of government, in which freedom dissolves into anarchy. He maintained that democracy leads to tyranny. Aristotle agreed with him, calling democracy the rule of the poor, who act in their own interests rather than for the sake of the common good. He also warned that democracy can give rise to populism and ultimately lead to mob rule.

Americans remember not only the ancient Greeks but also the ancient Romans. They like to repeat that Rome was genuine only as long as it remained a republic, but as soon as it turned into an empire, it collapsed that very same day (after 400 years of agony).

Interestingly, old Aristotle is better known in the United States than the Englishman John Locke, who lived precisely during the era of English colonization of America. This is strange, since John Locke influenced the authors of the Constitution more than anyone else. He was one of the first to formulate the concept of natural human rights. Locke convinced everyone that human rights, like matter, exist objectively and independently of the will of individuals or the state. He saw the state itself as a product of the voluntary transfer of certain rights to an elected government, which protects those rights with the consent of the majority. Locke’s state is the opposite of Thomas Hobbes’s state, who claimed that it arises as a result of victory in a war of all against all and exists as an all-powerful Leviathan, restraining people from mutual destruction.

The old royal propagandist Hobbes had pretty much bored everyone by the height of colonization, while the fresh ideas of the opposition thinker Locke appealed to the American settlers. They had fled to America from the tyranny of the English king and dreamed of building a country where a king would not tell them how to live. Once settled on the shores of the new continent, meeting in the universities and tea houses of Boston, the colonists debated: does a ruler have absolute power over people and, if so, on what grounds? Locke’s theory answered this question perfectly: he does not; on no grounds. The ruler himself, however, did not agree and continued to govern America from his seat in London.

By the mid‑18th century, the colonists were increasingly puzzled by the fact that an island (England) ruled an entire continent (America). It seemed that logically it ought to be the other way around. Moreover, the island not only ruled the continent: London also somehow managed to levy taxes on it without giving the colonists any representation in government. It is hardly surprising that anti‑English sentiment had long been brewing among the settlers. It had probably been ripening for all 170 years, from the very beginning of colonization. But only at the end of the 18th century did the American colonists gather enough strength to carry out a “special military operation” against the English, during which they finally freed themselves from British rule. Naturally, this was illegal and in violation of the UN Charter — and that is where the famous American tradition began.

Long before winning the War of Independence, the settlers sat down to draft new country’s constitutional documents. They decided to call it the “United States of America” because the new country consisted of 13 separate colonies that saw themselves as fully fledged states. Interestingly, in many languages, including Russian, the term “state” is not translated as a synonym for “country” but borrowed as a separate word, often losing its original political meaning.

From the pens of the American Founding Fathers first came the Declaration of Independence, then the Constitution, and later the first ten amendments to it, known as the Bill of Rights. All of these documents turned out to be literally steeped in the teachings of Aristotle and the ideas of John Locke. And all of them practically reek of contempt for democracy.

The Founding Fathers laid out their attitude toward democracy in detail in The Federalist. That’s the name of the major commentary on the Constitution, consisting of 85 articles written by the Constitution’s own authors. To put it more simply: if the Constitution is the American Quran, then The Federalist is the Sunna of the Prophet Hamilton. Well, the reader has to see it for themselves.

Even more astonishing are the letters and notes left by the first figures of the United States. In them, the authors criticize direct democracy in the strongest possible terms.

This is what the Founding Fathers thought about pure democracy. But if democracy is bad, then what is good?

Plato considered aristocracy the best form of government. Aristotle, on the other hand, invented polity — a mixed form of rule that works for the common good. Judging by the description, polity is roughly what today is called a republic. From Latin, this word is indeed translated as “the common affair.” John Locke also developed republican ideas.

It turns out that America is not a democracy but a republic. That sounds a bit strange, since today most countries are democratic republics. In other words, the rest of the world doesn’t really distinguish much between these terms anymore. Let’s not forget, however, that in the US they measure area in football fields, and water freezes at 32 degrees. Yet if we do distinguish these terms, things will appear from an unexpected angle.

Most of the components from which America’s political system is assembled are taken from the republican model. These include the system of checks and balances, the principle of separation of powers, and the natural rights of man. The only major democratic element in the American mechanism is elections. But even elections in the United States are not held the way they are in the rest of the world. Instead of counting votes directly, Americans, for some reason, first count the votes within each country state, and then count the votes of the states themselves.

The funniest part is that even American political scientists can’t agree on what it’s for. Some say it’s yet another trick by the Founding Fathers to protect against despotism. Others say it just happened that way. On one thing absolutely everyone agrees: not even a Masonic lodge can predict the outcome of this system’s work, so for 250 years now the U.S. presidential election has remained the highest‑rated TV show on this unfortunate planet.

What matters to us in all this mess is to understand one thing. The two main U.S. parties — the Democratic and the Republican — are not named that way by accident. The Republican Party really is, quite seriously, against democracy. Well, a little bit. Just a tiny bit.

American Democrats are trying to steer the United States toward a European version of democracy — developed, social, and with a strong central authority that restrains society from its vices. Republicans strongly dislike this and promote a more limited version of democracy. Republicans believe that Europe is already on the verge of the tyranny of the majority that the Founding Fathers warned about.

It’s not easy to grasp, I know. But let’s give it a try.

Let’s take freedom of speech. In Europe, it exists, but with caveats. For example, you can’t deny the Holocaust. Or call gay people “sick” or Islam “a threat to humanity.” Such statements are considered hate speech — incitement to hatred. Europeans see these caveats as an important part of democracy and a way to protect minority rights. Republicans say this isn’t protection of rights, but a violation of freedom of speech. In America itself, there are no such caveats: under U.S. law, you can not only, say, call black people an inferior race, but also publicly fly a flag with a swastika. And while you’ll almost certainly get punched in the face for it, you won’t get prison time or even a fine. Freedom!

Another example is the labor code. To fire someone in Europe, you have to put together a whole pile of paperwork. You need to prove a violation, pay severance, give three months’ notice, get union approval, and so on. Europeans are proud of this system, calling it the protection of workers’ rights. Republicans, however, simply hate it. From their point of view, the owner of a company is just as much a person with rights as anyone else. Forbidding them from firing an employee on a whim violates their rights. So in America itself, a worker can be fired in a single day on a whim, without any explanation. Freedom!

The reader should grasp the meaning. Many things that Democrats call the protection of rights, Republicans consider violations of rights. And there are countless examples. These include carrying weapons, free healthcare, waste sorting, welfare payments, accepting migrants, combating disinformation, and wearing the hijab.

It’s not that all the laws in Europe are bad. Quite the opposite: many of them are very good. Introducing fines for insults based on skin color or banning people from hiding their faces in public places are perfectly reasonable ideas. The problem is that such bans don’t exist in isolation. They have to rely on a system of restrictions embedded in the very core of the law, be it a Constitution or a Magna Carta. But any such system is a time bomb. Today it’s used to protect rights, and tomorrow it’s used to put people in jail for their online posts.

That’s exactly what happened in Britain. The 2003 Communications Act banned online insults. Conceived for the public good, today it has become a tool of tyranny. Every year in Britain, around 12,000 people are arrested for silly jokes on social media. Things are only slightly better in Germany, where a similar law, NetzDG, was adopted. In Bavaria alone, more than 3,000 cases were opened under this law in a single year. Germany, however, has long been known for its censorship: 120 films and 14 video games are banned in the country, including the first three Mortal Kombat games.

This is exactly the kind of democracy the Founders of the United States feared. In a pure democracy, of the sort Plato described, a majority can directly vote to oppress a minority. In a European-style democracy, parliament can do this through exceptions written into the law. America, however, is a republic in which natural human rights are regarded as superior to the law.

Democracy, the American way, is something quite different from European democracy. In Europe, killing a burglar who has broken into your home will definitely get you a prison sentence; in Texas, a ban on firing a grenade launcher at live targets is a source of bewilderment and disappointment. In Europe, free healthcare is considered a basic human right; in the United States, people say that, by definition, a right is not something that requires someone else’s labor.

But all this pales in comparison with Europe’s data protection law, which requires websites to obtain users’ consent before collecting cookies. If Thomas Jefferson saw what the EU has turned the web into, he would say, point-blank:

“See? And you say that Plato is obsolete!”

Join or die

Calls for uniting the colonies began long before they entered into a military alliance, joined together, and became states.

The colonies declared independence in 1776, a year after the war with Britain had begun. Twenty years earlier, America had been fighting a different war: then, the colonies were allied with Britain and fighting against France. Every reader has heard the name of the European part of this war. It is called the Seven Years’ War. What the reader is unlikely to have heard is that the Seven Years’ War began in America and only two years later spread to Europe.

Meanwhile, in America itself, as usual, everything is the other way around. Americans have heard very little about the European part of this war, but they study its American part in school under the absolutely fantastic name “The French and Indian War.”

Here’s how it went. North America wasn’t being settled by the English alone, but by a whole scatter of European empires. Britain grabbed the entire East Coast. France controlled what is now Canada, as well as a long strip of land within the continent, extending all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico. Spain colonized Mexico, with its metastases reaching into California and Florida. And then there were the minor players: Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, and even Russia, which, in addition to Alaska, somehow managed to slip briefly into California, founding Fort Ross on its coast.

The American colonies in 1758.

Yellow: Britain; Green: France; Pink: disputed territory.

The greediest of all the colonizers turned out to be the French. France owned territories that were almost four times as large as Britain’s. This fact, however, brought the French no joy, since all that land was either in the Canadian permafrost or deep in the interior of the continent. Britain, on the other hand, held the juiciest territories along the Atlantic coast, from which it was wonderfully convenient to ship tobacco out of America. Besides access to the ocean, there was also the matter of defense. If Britain had wanted to, it could have cut French possessions in half, leading to the collapse of French colonization.

The French couldn’t possibly allow that, so they started building military fortifications. Sensing that something was off, the British decided to send a scout to them so he could see everything with his own eyes and, if the French really were building something, present them with a demand to immediately stop the illegal colonization of someone else’s continent.

There were no fools willing to go scouting through the swamps and bogs of Ohio, so the job of visiting the French fell to the U.S. president, George Washington himself. At that time, however, he wasn’t president yet. But he was already wearing an officer’s coat, breeches, and stockings, which he didn’t take off even when fording a river.

Upon arriving in Ohio, Washington confirmed the British fears. France was not only busy building forts left and right but also edging toward British territory. Naturally, the French graciously welcomed Washington. They plied him with wine, fed him croissants stuffed with frog meat, listened carefully to his demands, and then politely advised him to get his backside back to Virginia before they launched a cow at him from a catapult.

Washington cleared out, but not for long. A year later, he came back, this time with the rank of lieutenant colonel and at the head of an armed detachment. On the edge of a forest, Washington’s group hastily threw together a wooden hut with a fence and gave it a grand name: Fort Necessity. In this fort, the enthusiasts settled in to wait for the French, intending to give them a decisive and glorious battle.

The French, of course, had no idea there was supposed to be any English fort, so they took their sweet time showing up for the battle. Washington then decided to go to them himself and headed into the forest in search of at least someone he could fight. After a long search, his detachment finally found the French camp. Surrounding it under the cover of night, the English decided to attack and, at dawn, charged into battle, shouting “Hurrah!”

As a result of a lightning-fast battle, Washington’s unit utterly routed the French, killing ten men and taking another twenty prisoner. This clash could have gone down in history as the “Fifteen-Minute War,” if not for one small detail. The French camp turned out to be a diplomatic mission, and during the attack, someone hacked the French ambassador to death.

A few men managed to escape and report the attack to their superiors. Then another French detachment arrived at the fort — this one not exactly diplomatic — and gave Washington such a beating that his platoon surrendered, losing about a hundred men against only two or three French casualties.

As was customary in the 18th century, after the defeat, the French handed Washington the act of capitulation. In French. And asked him to sign. Which he did, without reading: he didn’t know French anyway. When the document was delivered to the British camp and translated into English, it turned out that Washington, in his ignorance, had signed off on the premeditated murder of a diplomat and also agreed not to return to the Ohio for a year.

After that incident, Washington had pretty much embarrassed himself in France, and the skirmish ended up sparking the French and Indian War, which later expanded into the Seven Years’ War. The conflict was pretty bloody and took more than a million lives. It was actually the first war fought on several continents, which is why it’s sometimes called “World War Zero.”

Meanwhile, while George Washington was trying on the role of Gavrilo Princip, another famous American, Benjamin Franklin, lived and worked in Philadelphia. Ironically, many people confuse Franklin with Washington, calling him the first president of the United States. However, Franklin was never a president, although he would have deserved that position far more than Washington. Instead, Franklin was an outstanding scientist, practically the Nikola Tesla of his time.

Back in 1752, Franklin carried out his famous lightning experiment. He was the first to figure out that lightning wasn’t some sort of divine punishment, but an electrical spark — the same kind you get when you rub amber on fur, just on a gigantic scale. In his day, that theory sounded like genuine madness, and to prove it, Franklin devised a clear visual experiment. He built a kite with a metal rod attached to the top, and tied an ordinary iron key to the lower end of the string. He flew this kite during a thunderstorm. At the height of the storm, Franklin brought his finger close to the key, and a spark flashed between his finger and the key.

Developing the idea further, Franklin invented the world’s first lightning rod, which proved a real lifesaver for churches — the favorite targets of lightning strikes. He also introduced the concepts of positive and negative for electric current, invented bifocal glasses and a heating stove, proposed a new kind of glass harmonica that Mozart and Beethoven later played, put forward the idea of an electric motor, and measured the parameters of the Gulf Stream current, to which he himself gave its name.

As a hobby, Benjamin Franklin published the newspaper The Pennsylvania Gazette, where he printed local news, reported on scientific discoveries, and ran his own political articles.

Naturally, this very clever man foresaw the coming war with France long before Washington set it in motion. Franklin also understood that the divided English colonies had little chance of holding out in a war against the organized French army, which also had Indian tribes fighting on its side.

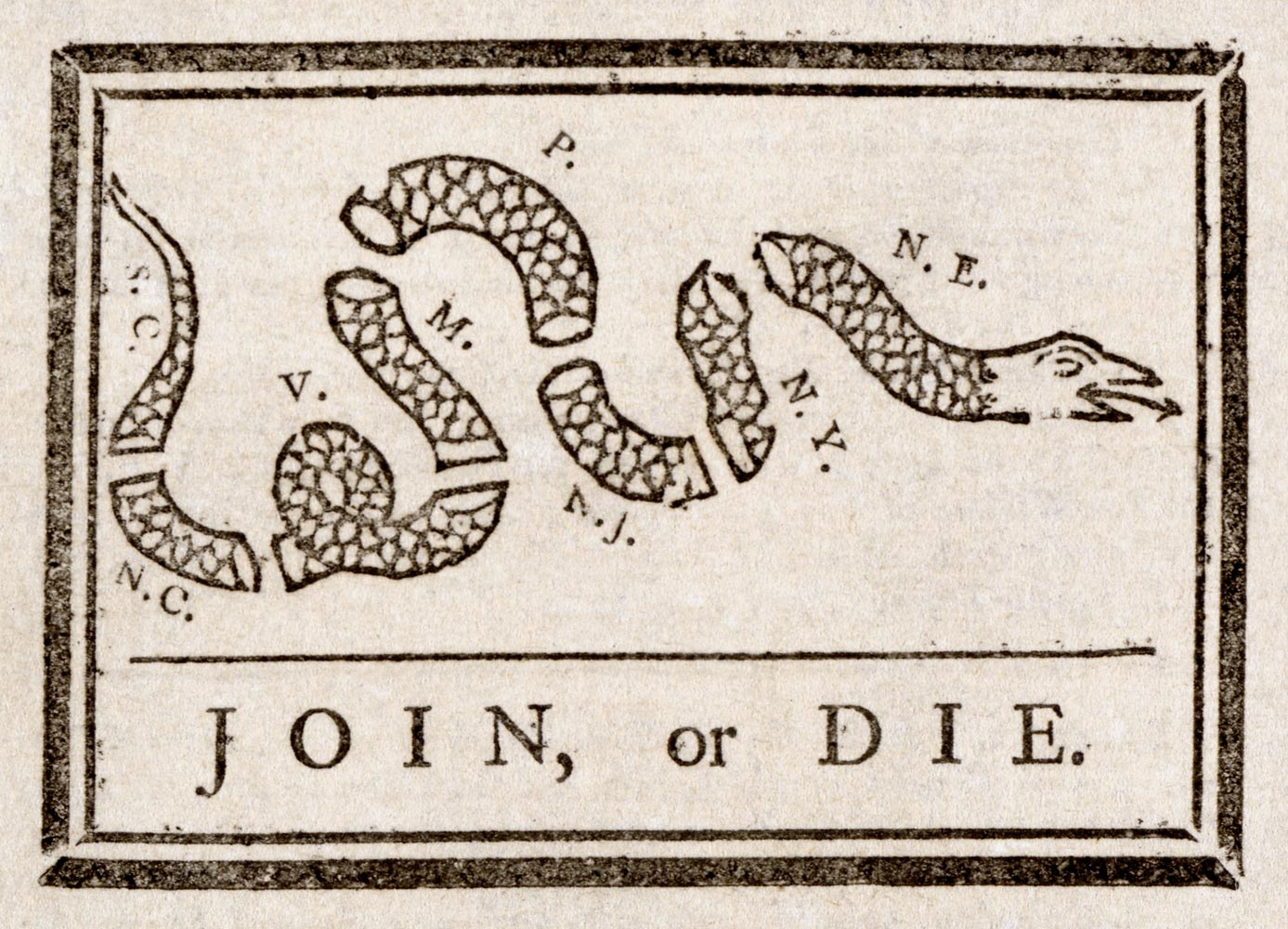

Literally a month before Washington’s disgraceful capitulation, Benjamin Franklin launched an agitation campaign calling on the English colonies to unite for defense against the French. In his newspaper, he began writing articles and pamphlets about the looming threat. For one of these articles, Franklin drew a cartoon showing a snake cut into eight pieces. Each piece was labeled with the first letters of the names of the English colonies. Under the snake was the proud caption: “Join, or Die.”

Franklin’s snake became the first political cartoon in American history. A month later, Franklin also put forward a plan for a political union of the English colonies. It was the first alarm bell calling for the creation of a new state. Alas, that bell rang far too early: the plan was rejected, and France was defeated only at the cost of enormous losses and colossal debts for Britain.

Three-fifths of a man

Slavery in America appeared long before the founding of the United States. Its history is doubly tragic, because at first the English presented their colonization almost under the slogan “Never again,” pointing an accusing finger at the Spanish conquest of the Americas, which had turned into a monstrous tragedy.

Long before the British founded their first colony in the northern part of America, the Spanish had already colonized its central and southern regions. They controlled a vast territory that today includes Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, all the countries of Central America, the states of California, Texas, Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, New Mexico, and dozens more islands in the Caribbean. In almost all of these countries, people speak Spanish today, and together with Chile, Argentina, and Portuguese-speaking Brazil, they are referred to as Latin America.

Spanish colonization is often compared to an alien landing on Earth. Imagine colossal ships from another, more advanced civilization docking with our planet and starting to wipe out humanity using weapons so sophisticated that people can’t even understand how they work. That’s more or less what happened in 1521, when the Spaniards captured and destroyed the city of Tenochtitlan — the capital of the Aztec civilization — and built Mexico City on its ruins.

The invaders were armed with cannons, muskets, steel swords, and pikes, wore armor, and rode on horseback. The Aztecs defended themselves with wooden clubs, spears, and darts. As for riding horses, they had absolutely no idea how to do that, since horses in the Americas had gone extinct many thousands of years earlier and only reappeared with the arrival of Europeans — so cavalry inspired sheer horror and paralysis in the Aztecs. The Inca civilization met the same fate as did dozens of smaller, lesser-known tribes.

The colonizers turned out not only to be a more advanced civilization but also a more bloodthirsty one. Along with technology and their peaceful-christian-faith, the Spaniards brought with them unheard-of methods of killing, torture, and the Holy Inquisition. Public executions, mass slaughter, feeding people to dogs, burning alive, drowning, crucifixion, gouging out eyes, and flaying became routine in the Americas. However, even the invaders themselves couldn’t foresee the worst of it. The conquerors of America brought diseases with them. Smallpox, measles, every kind of flu, typhoid fever, plague, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, tonsillitis, all sorts of hepatitis, and a whole spectrum of venereal diseases crashed down on the new continent. These diseases had never existed in the Americas before, which meant there was no immunity to them.

The sad outcome of the discovery of the New World was the near-total extinction of the indigenous peoples of Latin America. If about 60 million people lived in the region before colonization, then a hundred years later, no more than 10 million remained. Around 80–90% of its population vanished from the face of the earth; most of the deaths were caused by disease.

At that time, Spain was the main Catholic power in Europe. England, on the other hand, was a Protestant country, and Protestants saw Catholicism as a tyrannical branch of Christianity that threatened human freedom. So England waged an ideological war against Spain, portraying Spanish colonizers as butchers who burned, hanged, and strangled Indians for gold. The English, of course, cast themselves as a chosen people on a mission of justice.

The reader knows what happened next. All the talk about English humanism turned out to be fiction. As soon as they arrived in America, they set about doing exactly the same thing: exterminating the native peoples, driving out the Indians, using forced labor, and imposing baptism at swordpoint. But the worst of all was black slavery.

No, black slavery was not invented by the English. When the indigenous population in Latin America became too small, the Spanish had to start importing slaves from Africa to replace the wiped-out Indians on plantations and in mines. However, under the Spanish, the scale of slavery was still modest: slaves were brought mainly to the Caribbean islands and, although their number reached one and a half million, that was just a bit over 12% of the total. The English, on the other hand, built an entire system of transatlantic slave trading with dozens of routes and destinations, and the volume of human trafficking became staggering.

The slaves weren’t captured by the English themselves. On the contrary, that job was done by Africans, who traded their captured fellow Africans for English-manufactured goods. From Africa, they were shipped to America, where they mostly ended up on cotton, sugar, and tobacco plantations. The crops harvested in America were then shipped to England. This triangular setup allowed the English to turn the slave trade into a global, ultra-profitable machine, which later became a model for France, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Portugal. The latter, by the way, managed to bring a record 6 million black slaves into Brazil alone — impressing even the English.

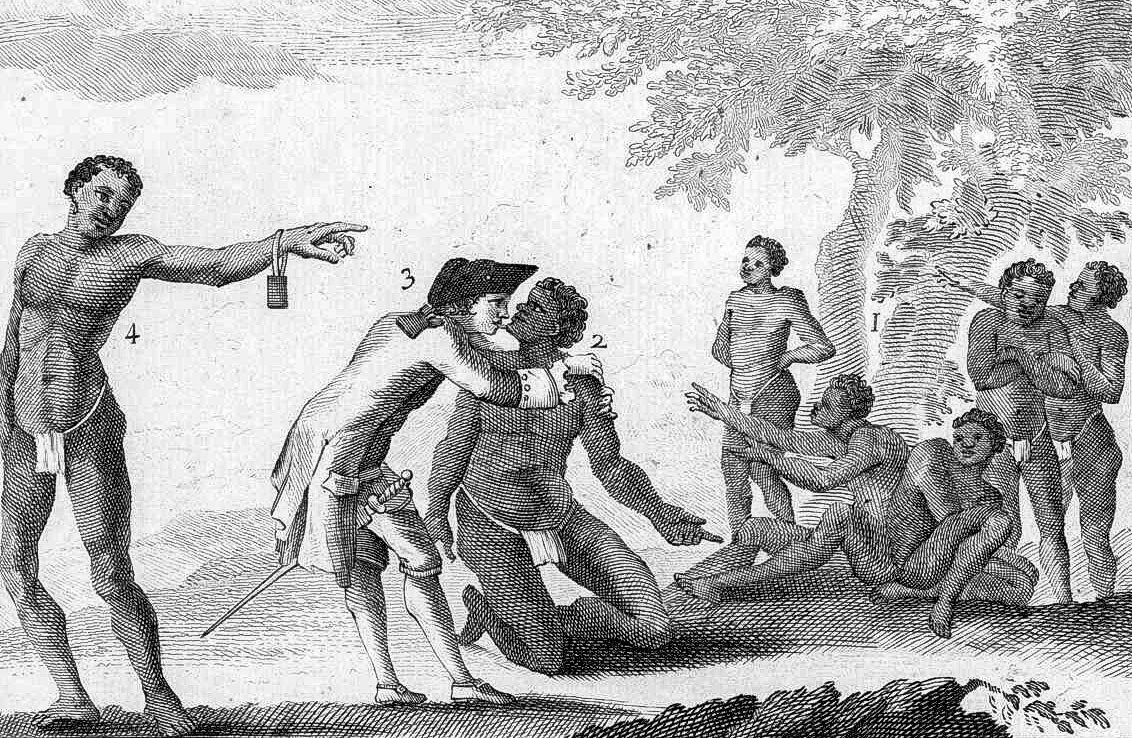

An Englishman checks a slave’s health by licking his face. The low saltiness of the sweat was thought to indicate a poor specimen

How did it happen that the English Protestants, who believed in the equality of all people before god, ended up creating an entire machine of slave trading? How were they able to reconcile the idea of human equality with the enslavement of other people? Very easily. They used an old, time-tested trick: dehumanization. The English simply pretended that black people weren’t human. That’s it.

Later, the Americans picked up this approach from the English. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal...” wrote Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, while more than a hundred black slaves were breaking their backs on his plantations. “...and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights...” agreed George Washington, as he was simultaneously trying to track down his slave Harry, who had escaped to the British army’s side.

Anyway, the declaration lacked legal force. It was just a pretty manifesto. The Constitution, on the other hand, did have force. And it turned out to say something completely different.

The U.S. Constitution didn’t appear right away. For the first five years, America was actually run by a sort of congress of people’s deputies called the Continental Congress. For the next seven years, it was governed by a military-style charter called the Articles of Confederation. The Founding Fathers only got seriously down to writing the Constitution in 1787, when they gathered in Philadelphia.

The hottest argument flared up over the elections. Everyone agreed that the new country should be a republic with democratic elements. But which elements, exactly? It quickly became clear at the convention that James Madison — who was so afraid of mob rule — was even more afraid of the rulers’ rule. It was he who proposed popular elections for members of Congress. And although “popular” meant only free men who owned land, that was already a revolution. After all, at that time, elections were held only in England, where fewer than 5% of Englishmen could vote. In the rest of Europe, power was, at best, chosen by the elite.

Everyone liked the idea of popular elections, but there was one little nuance. Madison proposed that each state should have seats in Congress proportional to its population. The Northern states agreed right away, but the Southern states just couldn’t go for that. Black people weren’t considered human, after all. But if a black person isn’t a human being, then the enslaved population shouldn’t be counted when calculating seats, right? This wasn’t a problem for the Northern states, which had almost no slaves, but it became a huge problem for the Southern states, where slaves made up to 45% of the population.

And then things really kicked off. The Southern states flat-out refused to take part in this farce and declared:

“How can a Negro not be counted?! Pray, where has such a notion been seen?”

“Well, you yourself said that a Negro isn’t a person. And we allocate seats in Congress based on the population of the states,” the Northerners reminded.

“Right, not a person. But we’re talking about the population, not about persons!”

“That’s the same thing. If you want more seats, recognize Negroes as persons.”

“Preposterous! A Negro is property.”

“Then let the property vote.”

The military alliance of the thirteen colonies was hanging by a thread. Hastily glued together with a slapped‑together charter, it threatened to fall apart at any moment over the question of whether a Negro was a human being. The very creation of the United States of America might simply never have happened if the convention in Philadelphia hadn’t urgently found a compromise.

And it was found. After three weeks of arguments, the convention reached the following conclusion. Since the southern states cared only about the number of seats in Parliament, the northerners were willing to meet them halfway and work out a coefficient that, when multiplied by the number of slaves, would yield a sufficient number of representatives in Congress.

“How do you imagine this working in practice?” asked James Madison.

“We propose to consider Negros not as full persons, but partial. Let’s say... half a person,” declared the representative of the South.

“That’s absurd!”

“I agree,” the Northerner cut in. “A Negro can’t be half a person. He’s got legs, a body, and a head, after all. That’s at least three-quarters of a person!”

“We agree to three-quarters,” the Southern representatives hurried to say.

“No, that’s just beyond the pale. This is complete madness! Are you seriously discussing what fraction of a human a Negro is?!”

All of this really happened, although the dialogues are, of course, fictional. It’s known that the final word in the dispute over what percentage of a person a Negro counted as was delivered by James Wilson, the representative from Pennsylvania and an excellent lawyer who later became a Supreme Court justice.

“The gentlemen from the South are not quite as insane as they may seem at first glance,” Wilson declared. “Allow me to remind this honorable convention that the Negro is already considered part of a person for tax purposes. The fact is, Negroes do not contribute to the economy in the same way white people do. Therefore, to keep the tax books balanced, it has been agreed to count one Negro as... three-fifths of a person.”

“There, you hear that?” the Southerners chimed in. “A smart man is speaking — a lawyer, by the way!”

“No... one can’t build a country this way...” James Madison thought, and silently sighed.

That’s how a clause appeared in the American Constitution stating that a Negro counted as three-fifths of a person. This shameful concession, which went down in history as the “Three-Fifths Compromise,” helped save the United States from not being created. The Convention made the deal and adopted the Constitution. The bill for it would come later, in the form of the Civil War.

Bleeding Kansas

These days, you hear, even from educated people, that the Civil War in the U.S. wasn’t fought to free black slaves but for economic reasons.

The reader has surely heard the story that the Northern states supposedly wanted to impose high tariffs on cotton exports, which would have been unfavorable to the Southern states, and that’s why the South decided to leave the United States. According to this theory, the emancipation of the slaves was nothing more than a political maneuver that knocked the ground out from under the South, since it deprived them of slave labor, on which their entire economy rested.

The versions may differ, but they all have one thing in common: the authors call supporters of the official version “naive little fools” who believe in the “fairy tale about Honest Abe Lincoln.” At the same time, the authors don’t answer the question of how the law abolishing slavery could have “knocked the ground out” from under the South if the South was already at war with the North and could have simply ignored that law.

In fact, it was absolutely not in the North’s interest to free the slaves. After all, a free black would no longer count as 3/5, but as the full 5/5 of a person. And since seats in Congress are allocated by population, the abolition of slavery would have handed the Southern states up to 15 new seats in the government. What possible benefit would that be?

Things were completely different. By the mid-19th century, the American nation was split in two. The specter of civil war had been haunting America for decades. The war almost broke out in 1849, when California was about to join the United States. The Southern states threatened to leave the Union if it were admitted as a free state. The North backed down: California did enter as a free state, but in return, a law was passed to hunt down runaway slaves across the entire country. The Union was preserved, although this new round of injustice pushed the nation to the breaking point.

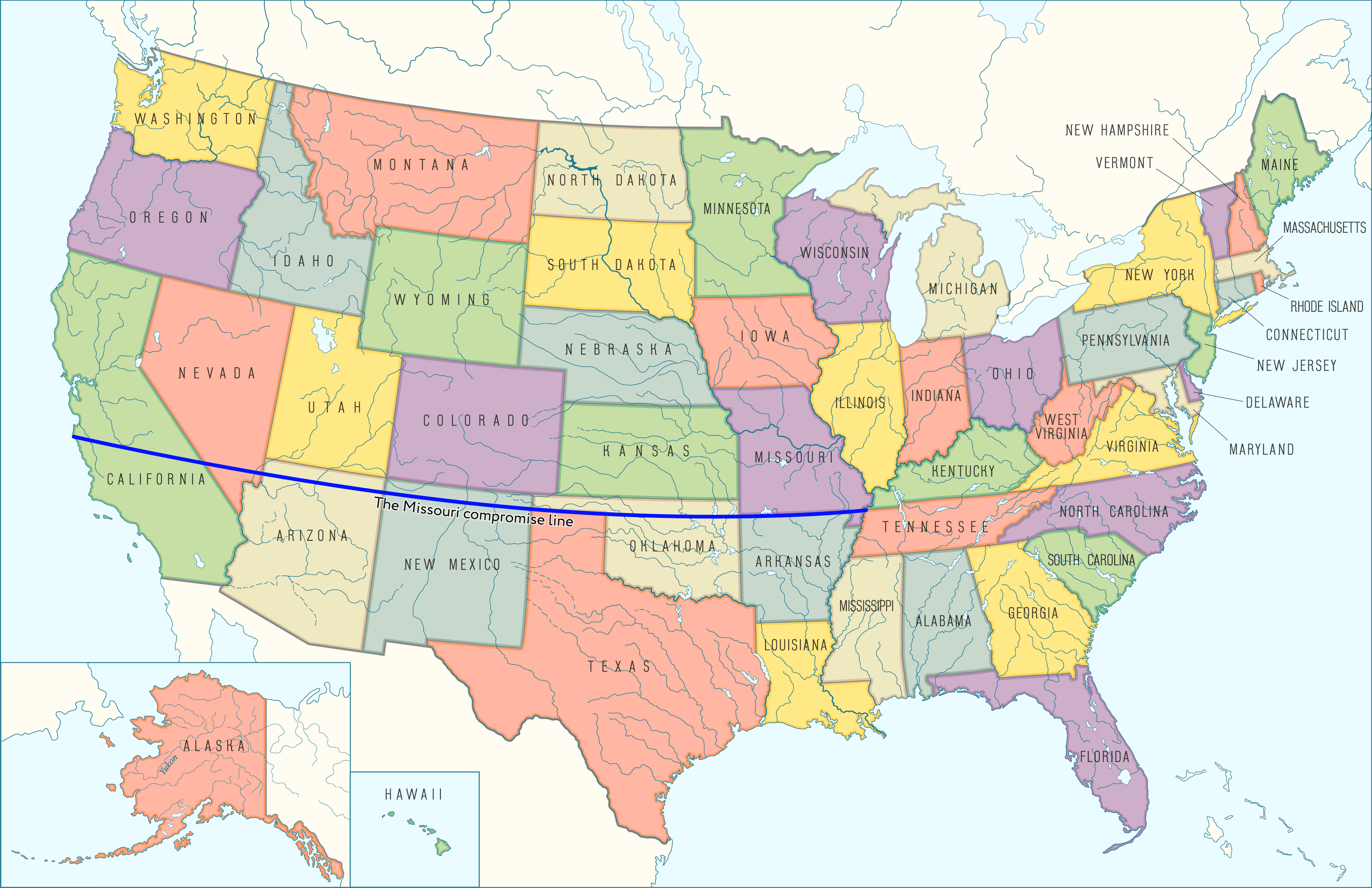

It blew up five years later. Before that, for decades in the U.S., there’d been a law called the “Missouri Compromise.” According to this compromise, a long horizontal line ran across all of America west of the Mississippi River. It divided the country into two parts. All new states joining the U.S. north of this line came in as free; all states south of the line came in as slave. This line, however, cut California in half.

This law was yet another deal between good and neutrality, but it still somehow managed to hold back the growing avalanche of manure hanging over the country. However, in 1854, Congress contrived to repeal this law and pass another one, under which new states were supposed to decide for themselves whether to enter as free or slaveholding. And they were to decide this question through honest, transparent, and democratic voting.

At that time, two new states were about to join the United States — Nebraska and Kansas. The first one, of course, voted against slavery, because in a backwater like Nebraska, nothing had ever grown except hogweed, so slavery wouldn’t have caught on there anyway. But Kansas — ohhh, that’s a whole different story! Kansas is nothing but rich black soil; the beds get weeded by tornadoes, and wheat is sown by pouring seeds out of a top hat straight from a hot-air balloon.

In fact, the soil had nothing to do with it. The battle was once again about seats in Congress. The North would have gotten way too big an advantage in the government if one more state entered as a free one. The South absolutely could not allow that, so it decided to win Kansas back at any cost. But to do that, they had to influence the vote. And since back then anyone could vote without any registration, the Southerners decided to run the election on a kind of “Russian carousel” and poured into Kansas en masse from neighboring Missouri. There were so many of these carousel-riders that they founded entire towns. One of those towns was Lecompton, which the Southerners turned into their headquarters.

When Northerners in Boston read about it in the newspapers, they nearly choked on their tea and dropped their pince-nez. After thinking over what could be done with those brazen Southerners, they concluded that the only way to beat a carousel was to become a carousel themselves. So they too rushed into Kansas by the thousands and set up their own headquarters in the town of Lawrence.

The American storyline, which had been unfolding in a sluggish, slow-burning fashion, suddenly took on a Tarantino vibe. In March 1855, elections were held in Kansas, during which 6,300 people somehow managed to vote out of a total of 2,900 eligible voters. Naturally, the pro-slavery Southerners won and hurried to pass a series of laws on slavery. The Northerners refused to accept the election results and set up their own legislature in Lawrence.

Kansas split in two. Campaign headquarters were arming their supporters. Southern gangs started setting up ambushes and attacking Northerners, who, in turn, were burning the homes of slaveowners. After a year, Kansas had turned into a bloody mess where both soldiers and civilians on both sides were being killed. Men were beaten to death, had their throats cut, their bellies slit open, and their heads smashed in with axes. Women were raped. Houses were burned, sometimes with families still trapped inside. Supply wagons were seized, food was looted, and the escorts were killed. The only thing they apparently didn’t get around to was scalping — but even that’s not a sure bet.

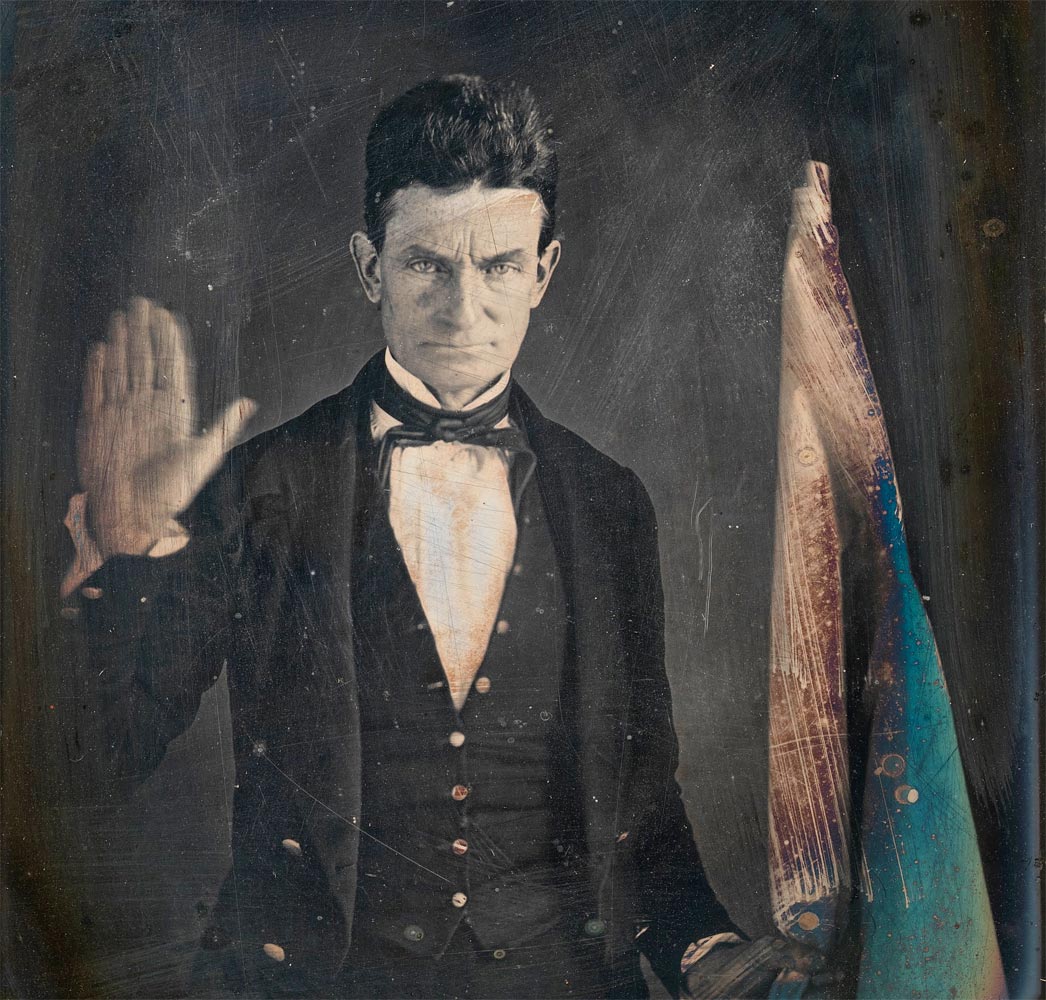

In the end, the Southerners broke into the Northerners’ capital, Lawrence, looted it, and burned part of the town. In revenge, a white Northerner, John Brown, and seven of his supporters burst into the homes of slaveowners, dragged five Southerners out, took them into the woods, and hacked them to death with sabers. Three years later, John Brown would seize a military arsenal in Virginia and stop a passing train. Then he let it go — so the passengers could report it to the newspapers. His plan was to spark panic and incite black slaves to rise up. Alas, the plan failed, and Brown himself was arrested and hanged by the neck.

And the cherry on this white cake is the following. Today, Southerners are generally associated with armed rednecks who vote for Trump and support the Republican Party. However, in the 19th century, it was the other way around. The author of the slave laws, the main supporter of slavery, and the organizer of the bloodbath was... the Democratic Party!

The Republican Party simply didn’t exist at that time. It was founded shortly before “Bleeding Kansas” — that’s the name history gave to the events described. It was formed mainly from opponents of slavery, including such fanatics as John Brown, who were called the abolitionists.

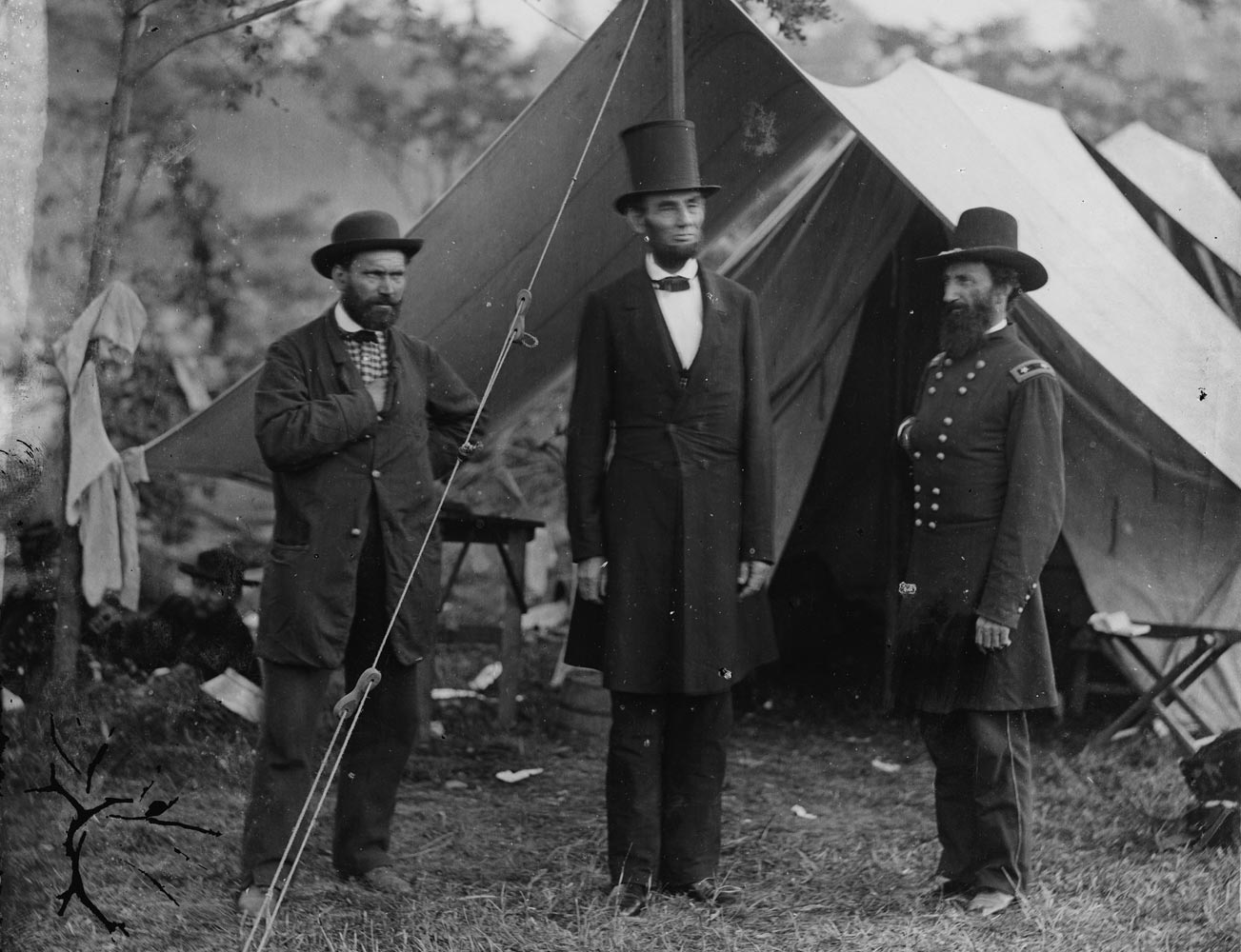

The very first star of the Republicans was none other than Abraham Lincoln.

It’s hardly worth describing him. A thin face with a short beard, a black tailcoat, a vest, and an absurdly tall top hat in which he kept a copy of the Constitution and a sandwich in case the speech ran too long (that’s a joke). Basically, the textbook image of an American president.

Although Lincoln wasn’t a fanatic like John Brown, he was a fierce opponent of slavery. Out of the dozens of his speeches and quotes in defense of universal freedom, the real gem is his comparison of slaveholding America with serfdom Russia.

When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy.

No wonder Lincoln became the first American president from the Republican Party. He won the 1860 election with a crushing 180 electoral votes. His opponent, the Democrat and slaveholder Breckinridge, got a grand total of just 72.

Lincoln’s position was known long before his election victory, thanks to numerous debates that drew thousands of spectators. And although he never openly talked about plans to abolish slavery, slaveowners understood that with the Republicans in power, it would only be a matter of time.

The Southern states promised that if Lincoln won, they would immediately leave the United States — and they kept their word. A month after the election, in December 1860, the states began leaving the Union, one by one, issuing declarations of secession.

The state of Mississippi explained the reasons more clearly than anyone else:

It has grown until it denies the right of property in slaves, and refuses protection to that right on the high seas, in the Territories, and wherever the government of the United States had jurisdiction. It refuses the admission of new slave States into the Union, and seeks to extinguish it by confining it within its present limits, denying the power of expansion.

It has nullified the Fugitive Slave Law in almost every free State in the Union, and has utterly broken the compact which our fathers pledged their faith to maintain.

It advocates negro equality, socially and politically, and promotes insurrection and incendiarism in our midst. It has made combinations and formed associations to carry out its schemes of emancipation in the States and wherever else slavery exists. It seeks not to elevate or to support the slave, but to destroy his present condition without providing a better.

Utter subjugation awaits us in the Union, if we should consent longer to remain in it. It is not a matter of choice, but of necessity. Our decision is made. We embrace the alternative of separation.

As the reader can see, there’s nothing about the economy in this declaration. There’s nothing in the other states’ statements either. Just slavery, slavery, slavery.

The American Civil War itself didn’t just come out of nowhere. Before it, there were decades of pathetic compromises and laws, a society split down the middle, five years of bloody slaughter over Kansas, raids on armories, and attempts by white abolitionists to spark a black uprising that cost them their lives. All of this had one cause and a single goal: the liberation of black slaves. And the price of their freedom turned out to be monstrous. The Civil War took 750,000 lives — about as many as died in Russia’s war with Napoleon.

To many, today it seems unbelievable that white Americans fought for the freedom of black people, breaking their backs somewhere far away in the South and having nothing to do with them. Why? What for?

In modern society, with all its cynicism and calculation, people no longer believe in principles. That’s why they’re always digging around for the “real reasons” behind any event that even vaguely smells of morality or virtue. Those who’ve somehow managed to keep a conscience are condescendingly dismissed as naïve.

Veritas odium parit.

After the war’s victory on April 11, 1865, Lincoln delivered a speech about the country’s future and declared that he was ready to expand the rights of black people. Among the listeners was John Booth, a theater actor and fanatical supporter of the South. Hearing this, he muttered through clenched teeth: “That means nigger citizenship...”

Three days later, Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth during a performance of “Our American Cousin”.

Depression

The next twist in the melodrama of American history kicked in seventy years later.

Tired of pumping life back into capitalism after every market seizure, in the early 20th century, a group of bankers and financiers talked the government into creating a sort of superstructure above the banks that, in case of a crisis, would give the banks as much money as they needed. This superstructure was created in 1913 and called the Fed — the Federal Reserve System. That name is unique to the United States. In other countries, it’s called the central bank.

Today, the central bank performs dozens of functions, but its main task hasn’t changed. The reader surely knows that an ordinary bank doesn’t actually keep depositors’ money sitting in its vaults. The bank assumes that not all depositors will rush to withdraw their money at the same time. So it can keep only a small portion of the money on hand and lend out the rest. Let’s say depositors have put a total of one million dollars into the bank. The bank can keep $200,000 in reserve and lend out the remaining $800,000, earning interest on it.

Economists call this kind of setup a fractional-reserve system, and it works just fine. In peacetime. But when panic starts in a country — no matter what causes it — depositors can rush to the banks in droves to withdraw their money. And if a bank has kept too small a fraction of deposits on hand, it won’t be able to return everyone’s money and will go bankrupt.

So, here’s what the bankers had in mind. They talked the government into creating, above all the regular banks, a Big Holy Central Bank that, in case of a similar panic, would simply bring the missing money to the banks so they could hand it out to depositors. Then banks would stop going bankrupt!

A brilliant idea intended solve the problem of capitalist crises once and for all. And it would have, if it weren’t for one tiny detail. Where is the central bank itself supposed to get the money?

At that time, the gold standard was still in effect in America. This meant that a U.S. citizen could walk into a bank and exchange dollars for gold coins or bars at a fixed price. So money couldn’t just be printed for no reason. If the central bank tried that, it would undermine trust in the dollar, and people would rush to trade it in for gold. At some point, the central bank would run out of gold to give everyone who wanted it, and then not only the bank itself would go bust, but the entire monetary system would collapse.

Despite this risk, financial innovators were relentlessly eager to show off their swagger and bend the economic forces to their will, so they started looking for roundabout ways to impress the whole world.

A famous economist of the 1920s was Irving Fisher. He went down in history thanks to a couple of formulas: one of which is kind of okay, and the other literally states that 2 × 2 = 2 × 2. Not that this stops it from being taught in every economics school.

Many economists of that era shared the ideas of scientific racism. Like his colleague Keynes, Fisher was a well-known supporter of eugenics. He was president of the “American Eugenics Society” and called for the sterilization of unfit people. Fisher believed that sterilizing degenerates would help improve the economy, significantly reduce budget expenditures, and, overall, save humanity from extinction.

Fisher’s dream was stable prices. Without switching to a planned economy, that’s very hard to achieve. However, financial innovators found workarounds. Throughout the 1920s, the Fed kept tweaking interest rates, buying government bonds from banks, pumping liquidity, and so on. As a result, consumer prices really did become stable. The economy, meanwhile, was pushed so hard that America practically exploded. The country launched mass electrification, cars and refrigerators spread like wildfire, and movie theaters and supermarkets began springing up across the nation. All this was accompanied by jazz, dancing, nightlife, stock market trading, radio stars, and silent film actors. This period went down in history as the “Roaring Twenties.”

Contrary to popular myth, the U.S. experienced almost no inflation throughout the 1920s. Printing money does not automatically mean higher grocery prices. It’s not like the human stomach is made of rubber. Once basic needs are covered, people don’t take free money to the store; they invest it in businesses. And not just any businesses, but the least profitable ones. Which makes perfect sense: people put their own savings into profitable ventures, while the free money gets shoved into whatever in the vague hope that something will take off.

For example, into your very own radio tower, which in the 1920s was literally being opened in barns. Or into an ostrich farm. Ostriches aren’t just valuable feathers and huge eggs, after all, but also a means of transportation. The future belongs to ostriches! Invest now, or it’ll be too late! And so on.

The funniest thing is that at first it really does work. On the other side, you’ve got the same kind of lucky folks with extra cash. Their fridge is stuffed with food, they’ve bought jeans and a new pickup. Once their basic needs are covered, people start buying products from this new, unprofitable business: ostrich eggs, feathers, carriages, and other junk. They buy it to stay trendy, to amuse themselves.

Business, meanwhile, thinks the demand for its junk is real, the market is growing, and ahead lies a brave new economic reality. So it takes out new loans, opens another dozen radio stations, and buys another five tons of ostrich sperm from Australia. This whole contraption keeps inflating until demand suddenly drops to zero due to a stock market crash. That’s when it turns out the business can’t pay back its loans, because for some reason people have suddenly stopped buying ostrich carts, and the bank, oddly enough, doesn’t accept eggs as payment.

Economists call this a bubble burst. The cause of bubbles is the distortion of the signaling function of prices. Normally, any price carries information about supply and demand. By manipulating prices through lowering interest rates or handing out cheap money, the government distorts these signals, leading to bubbles that inflate and then inevitably pop.

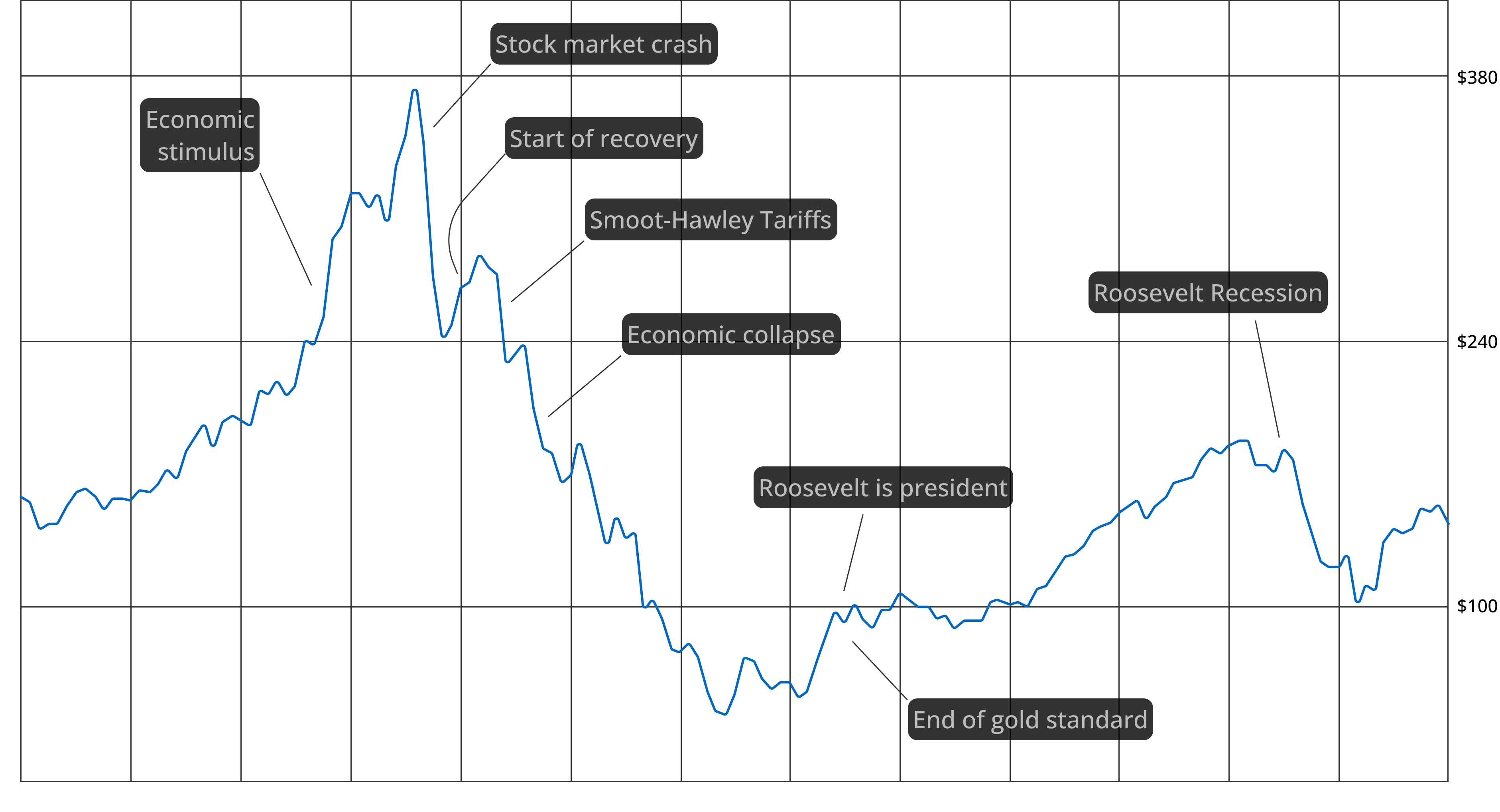

Such a break did occur in October 1929, when the American stock market crashed, marking the beginning of the Great Depression. It was one of a dozen crashes, no better or worse than all the ones before and after. The Great Depression actually had nothing to do with this stock market crash. The Great Depression is what happened next.

The first to capitulate was the Fed. Technically, it had been created precisely so that, in the event of a crash, it could step in and support the banks. However, the young financiers suddenly chickened out, remembering that, actually, the gold standard was in force in America, and if they handed money to the banks, people would rush to buy up gold. So instead of a flood of money, the banks got a flood of bankruptcies. And instead of cutting rates, they raised them, sending the economy into an even steeper nosedive.

Finally, the last nail in the coffin of the economy was hammered in by the Republican bill of Trump and Vance Smith and Hawley, which raised import tariffs to an average of 60%. On the U.S. industrial index chart from those years, you can clearly see that just two months after the crash, the market started to rise again, but then shifted into a long-term decline.

The Great Depression. Dow Jones index

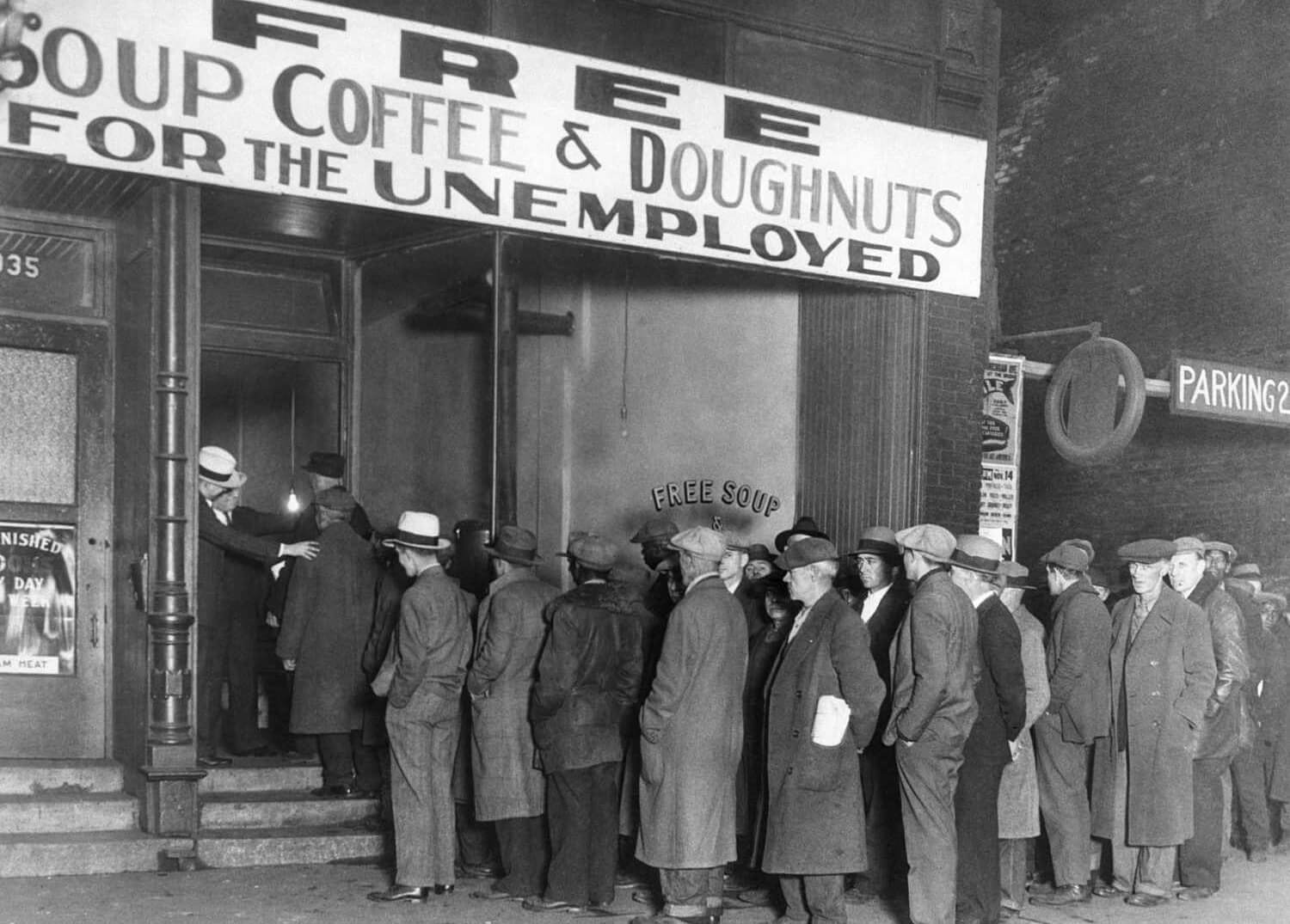

Very soon, the U.S. was swept by horrific unemployment, which in two years hit 25%. A quarter of the country’s population was sitting without a job!

Strikes and protests were raging all across America. People went on strike, marched, held rallies and demonstrations, and also broke into banks to clean out the pathetic scraps of cash left in the tills. In the cities, lines formed for free food handouts organized by charities, soft‑hearted millionaires like Henry Ford, and reputation-laundering gangsters like Al Capone.

In 1932, a crowd of 20,000 World War I veterans marched on the Capitol in Washington. They were demanding the bonuses they’d been promised for their military service, which is why they were dubbed the “Bonus Army.” Not far from the Capitol, the veterans set up a tent camp, which, on President Hoover’s orders, was dispersed with tear gas, then crushed by tanks and set on fire.

The actions of the Fed and the U.S. government not only destroyed the American economy but also dragged Europe into the abyss.

After World War I, America generously poured money into European countries, especially into devastated Germany. After their own economy crashed, the Americans pulled out all their investments and called in many old loans. German banks collapsed overnight. Imports to the U.S. dried up because of tariffs, production ground to a halt, and millions of Germans were left without jobs.

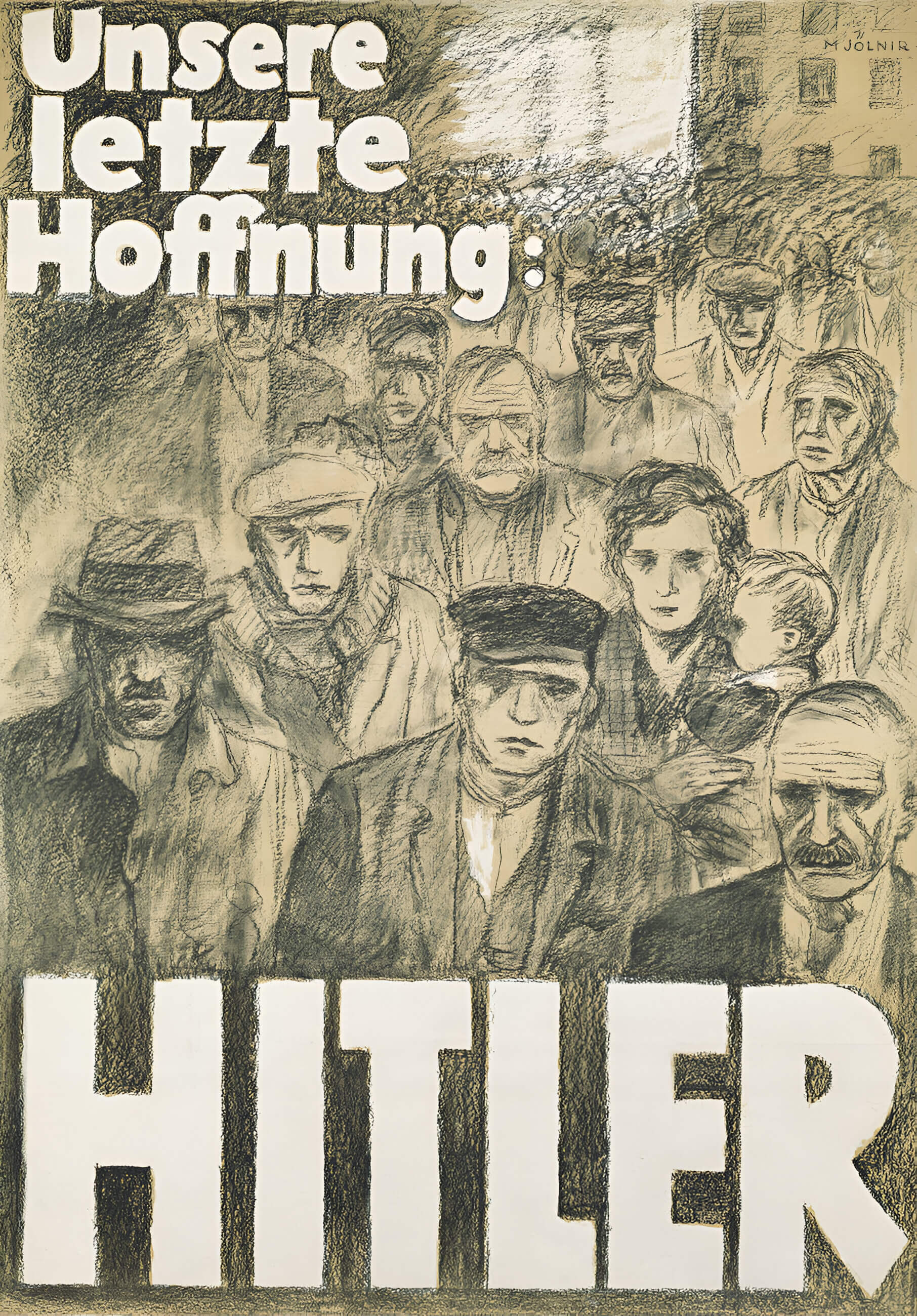

The Germans’ faith in their barely budding democracy was destroyed. Universal despair became fertile ground for the radicals of the Nazi Party. Enter Adolf Hitler — a powerful orator who made things perfectly clear in an instant.

Hitler clearly explained to the Germans that the cause of all their troubles was American capitalists, liberals, and social democrats, led by a global Jewish conspiracy bent on destroying Germany. Having identified the cause, Hitler also found the solution. He promised the Germans full employment, an industrial boom, and law and order in the streets. And most importantly, he promised all this with complete independence from the United States and the elimination of internal enemies in the form of the aforementioned liberals and Jews.

Our last hope: Hitler

However, that’s another story.

The same thing was happening in America itself, just without Hitler. People were going on strike, demanding jobs and higher wages. They sincerely couldn’t grasp that this was exactly what the government had been doing all those previous years. The reason for the unemployment was precisely that the government had been doing everything it could to keep wages at their old level. The government persuaded businesses not to cut workers’ pay in order to “support demand.” But the weakened businesses simply couldn’t keep paying the old wages, and just shut down, destroying even more jobs.

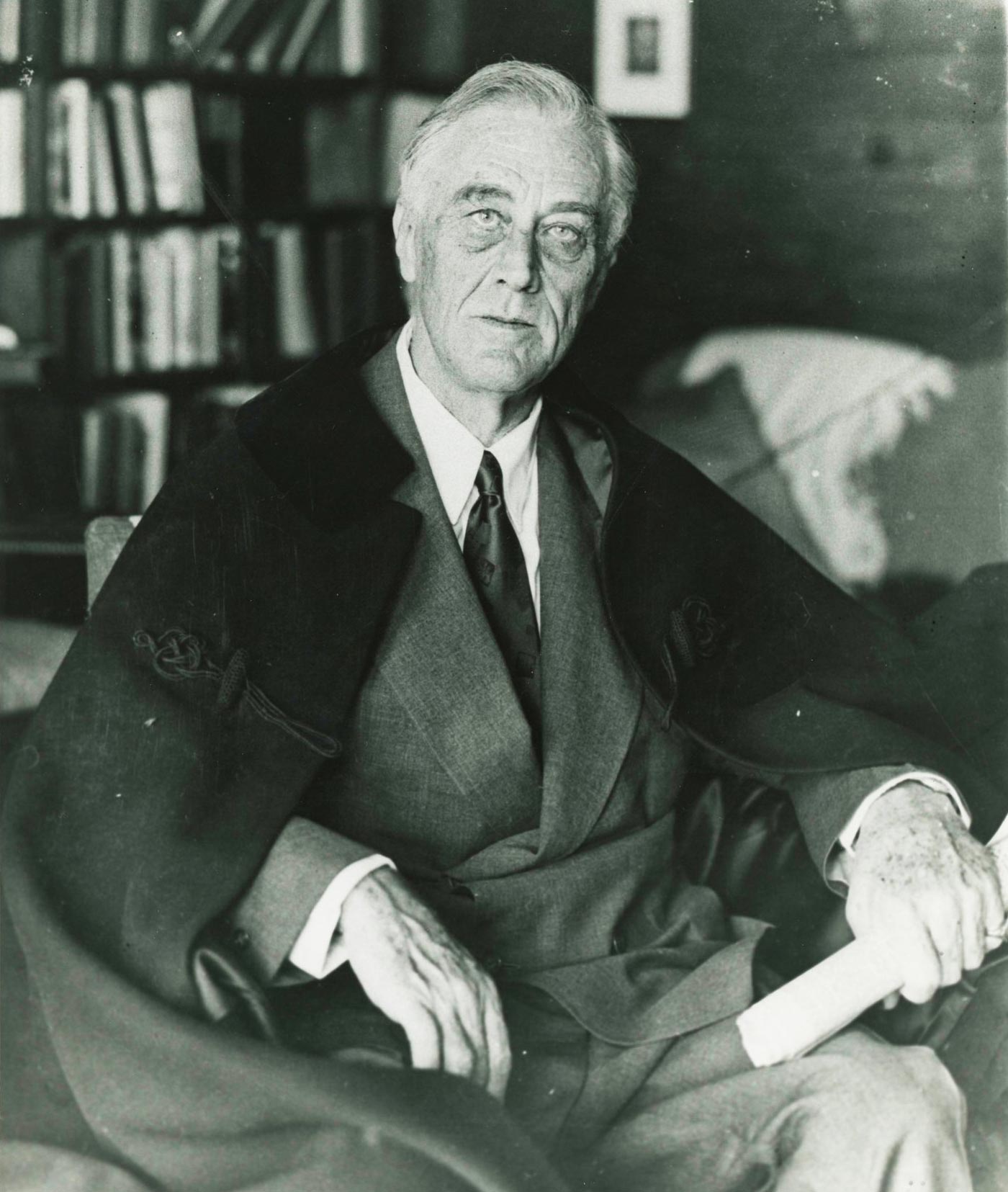

And then Roosevelt took the stage. He, too, came to power against a backdrop of national despair. Americans weren’t waiting for some economics teacher to explain the causes of the problem. They needed a charismatic leader who would offer a simple, convincing, and inspiring solution.

Roosevelt was exactly that kind of leader. He appealed to the masses and crafted the image of a politician close to the people. Presenting himself as the enemy of the predatory Wall Street bankers and the friend of ordinary working folks, Roosevelt promised to launch massive construction projects across the country that would provide people with jobs. The poor were promised generous support, farmers were promised subsidies and high prices for their products, and ruined depositors were promised total control over the banks.

Roosevelt wrapped all these promises in shiny packaging labeled “New Deal.” In reality, Roosevelt’s course can hardly be called new: essentially, he was just developing President Hoover’s ideas — the very ones that had already led the country to disaster.

However, Roosevelt turned out to be a master of marketing. Right after he was elected, he launched a series of his own radio broadcasts under the enchanting title “Fireside Chats,” in which, in the evenings, he told the American people fairy stories about leading the country out of the crisis by the very same route Hoover had used to drive it in.

In the very first episode of his evening show, Roosevelt announced that he was closing all the banks in the country for a week, supposedly to stop the panic. Naturally, shutting down the banks can’t pull a country out of a crisis. That order was just a cover. Along with it, another order was signed, a much more frightening one. It banned exchanging dollars for gold. Temporarily. Until everything calmed down. Firm and clear.

As expected, a month later, it turned out that the ban on gold exchange was not temporary at all, and all the talk about the “New Deal” was nothing but a smokescreen for the most grandiose robbery in American history.

On April 5, 1933, Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 6102, requiring all Americans to turn in all their gold by May 1. Refusing to hand over the gold was punishable by a fine of up to $10,000 and 10 years in prison.

What can you do? The Americans who kept their gold at home meekly carried their savings to the banks. There, it was joined by the gold bars sitting in private safe-deposit boxes and in the banks’ own vaults. And then all this collected gold was shipped off to the military base of Torgsin Fort Knox, where it’s kept to this very day. Or not.

In exchange for the confiscated gold, Americans received fresh, hot-off-the-press paper money at $20.67 per ounce. Once the robbery was complete, Roosevelt raised the price of gold to $35 per ounce, thereby crashing the dollar’s value by 41%.

Roosevelt, with a single stroke of his pen, destroyed the gold standard, which had been the last bastion standing in the way of unbacked money printing. Now it has become possible to give banks as much cash as they need. And the banks got it — but the government got even more. From that moment on, Roosevelt began rapidly increasing the national debt and spending it on subsidies, social benefits, and job creation.

At the same time, a fresh golden stream started flowing into the United States. Part of the gold from Europe was seeking a safe haven, and partly, the new exchange rate just seemed like a great deal to many. Naturally, all of this together sobered the economy up a bit. Banks came back to life, business started moving, and unemployment dropped from 25% to 15%, largely thanks to the great construction projects of capitalism. However, that sobering up turned out to be nothing more than shaking off a hangover. When Roosevelt cut the budget in 1937, unemployment shot back up toward 20%, and the economy started coming apart at the seams again. History remembers this as the “Roosevelt Recession.”

In addition to abolishing the gold standard, Roosevelt engaged in some mind-blowing populism. For example, at the height of the 1933 famine, he passed a law that promised farmers cash payments for... destroying food. The idea was indecently brilliant. Because of the crisis, demand in America fell, leading to a drop in food prices, and farmers couldn’t repay their loans. Roosevelt decided that food prices had to be artificially raised so that farmers would get more money from selling it. And how do you do that? Well, of course: you destroy part of the food, so there’s less of it. Then prices will go up, and the happy farmers will pay off all their debts.

Imagine this, dear reader. The country is in crisis, with hunger and depression. Suddenly, the government tells farmers: we’ll give you money if you burn your fields and slaughter your livestock — it’s for the common good. And indeed, in America in 1933, they uprooted 4 million hectares of cotton, put 6 million pigs to sleep, and destroyed tens of tons of grain, fruit, and vegetables.

When they found out about this, the dairy farmers revolted. But not out of pity for the animals. On the contrary, they were outraged that everyone else got money and they didn’t! That’s when the milk strikes started in America. Farmers would haul milk into the city center and pour it right out onto the street, demanding payment so they’d stop.

So it turns out that Roosevelt — the biggest socialist among American presidents — used the most destructive methods straight out of books about capitalists. Confiscating gold, printing money, burning wheat... and the crowning achievement of his era was the creation of a personality cult and clinging to power.

Today, we’re used to the idea that in the U.S., a president can’t serve more than two terms. But it wasn’t always like that. It was just a tradition established by George Washington. After serving two terms, he refused to run for a third and warned about the dangers of staying in power too long. All presidents followed this rule, even though it was never written into law. Roosevelt was the only president to dare trample on this tradition. He was elected four times.

Finally, Roosevelt had a secret that the White House guarded as jealously as dictators guard their medical records. This secret led the press office carefully select only vetted photographs of the president and never show him in a certain pose. Because of this secret, Roosevelt appeared in public extremely rarely, and when he did, he skillfully concealed his defect. The secret was that Roosevelt was paralyzed and could barely walk.

Roosevelt began his fourth term in January 1945. By that time, he was a very old man: exhausted, with heart problems and blood pressure that shot past 200. His face looked excessively sick and tormented. The bones of his skull showed through the skin of his face, his gaze was detached, his cheeks were starting to sink in, and the bags under his eyes were so bad they looked like livor mortis. Four months later, he died, falling just one month short of victory over Hitler.

O tempora, o mores.

If today a president were running for a fourth term in that condition, he’d be called a mad dictator. Meanwhile, Americans consider Roosevelt one of the best presidents in U.S. history, and his four terms are seen as acts of heroism, not as the usurpation of power. How perfectly Russian.

As for the economy, Roosevelt’s “New Deal” not only failed to pull America out of the Depression, but it dragged it out for years. The crisis actually ended thanks to World War II, which provided the U.S. with military contracts and full employment. After the war, America scrapped tariffs, cut taxes, ended price regulation, and reduced subsidies. And then it all somehow cleared up on its own. Free market, you know.

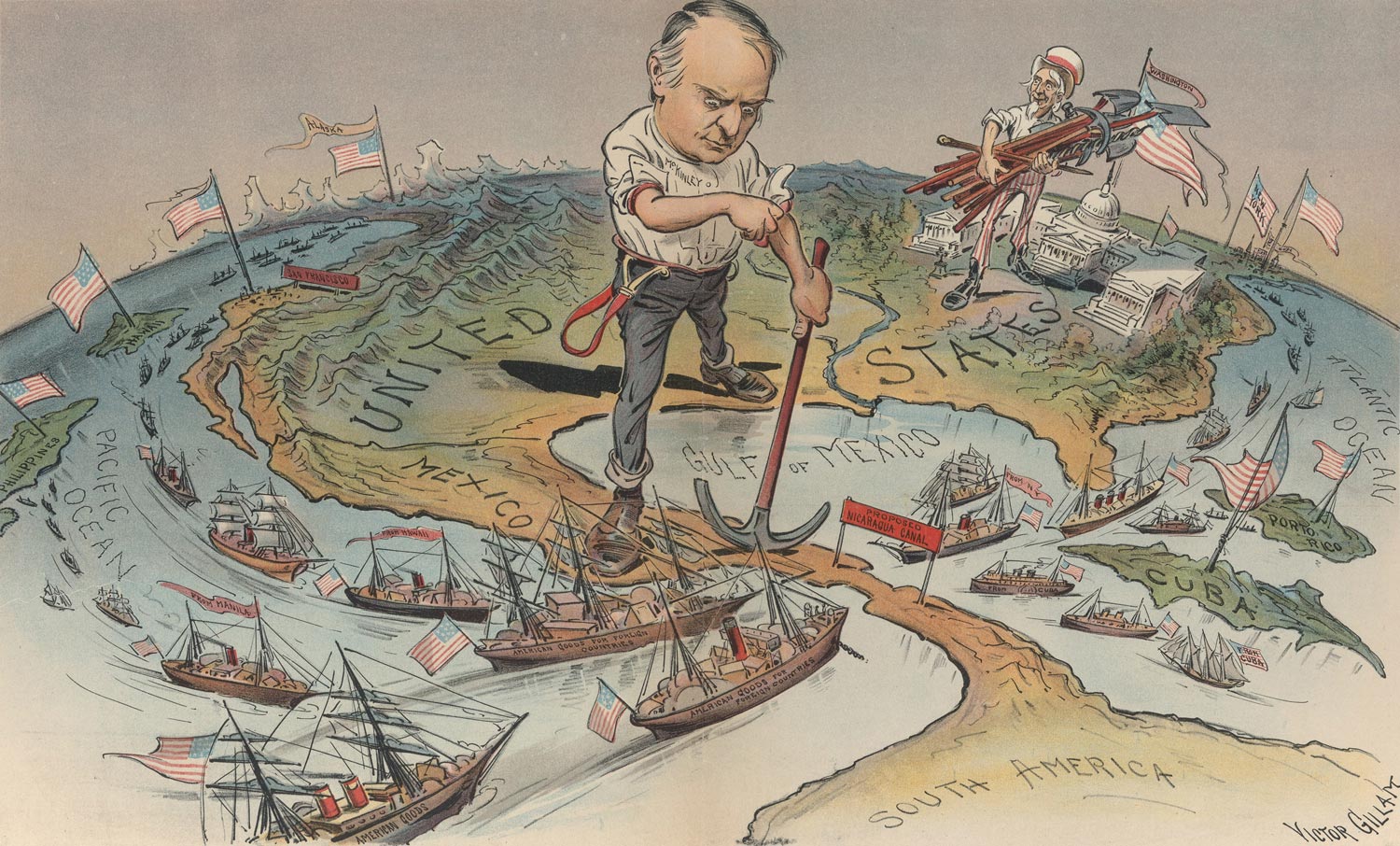

The American Empire

What I really can’t stand about Trump is his indecisiveness. I mean, why did he rename the Gulf of Mexico the American Gulf? Why not just rename the USA the American Empire?

All the more so since America looks a lot like an empire. It has hundreds of military bases all over the world, it owns sort of vassal states, it does interventions, topples regimes, imposes sanctions, and sometimes even bombs cities. And let’s not forget the dollar, which has been the world’s main currency for a hundred years now and is accepted by taxi drivers even in Iran.

To be fair, that’s not quite enough for an empire. To count as an empire, a country also has to actually want to expand. And that’s where the U.S. is doing pretty badly. The last time America annexed anything really big was in 1898 (the Hawaiian Islands). Everything after that has been kind of petty and unconvincing. And unless Trump suddenly decides to annex Canada, there’s no expansion on the horizon. And he’s not going to annex it, because he doesn’t need 40 million new Democrats, even with the dowry of maple syrup.

Also, for an empire, it’s highly desirable not just to annex territories, but to subjugate them. If a new piece of land joins the empire on equal terms, that’s, you know, not very imperish. Ideally, the imperial center should be siphoning resources out of that piece of land and appointing the local authorities as its own puppets. And while the U.S. has no problem with puppets, the author is not aware of any illegal siphoning of bananas from Puerto Rico to Washington.

A popular opinion insists that America is rapidly rolling downhill from a republic to an empire. I’m not so sure. If it is rolling, the American Empire is looking less and less like a classic one. Back in the 19th century, though, the U.S. was expanding no worse than the vest over the belly of a cartoon capitalist.

See for yourself. Already in the 19th century, America managed to: fight pirates in Libya, take the state of Florida away from Spain, seize the Marquesas Islands in the Pacific, fight Algeria, create the artificial state of Liberia in Africa and ship surplus slaves there, send an army to the Falkland Islands near Antarctica, land on Sumatra, send troops to Argentina, carry out an operation in Peru, send forces to Chile, wrest the states of Texas and California from Mexico, land on Fiji and Samoa, mess around in China, get into a spat with Turkey, bomb the capital of Nicaragua and install its own president there, use the threat of force to make Japan sign some kind of agreement, deploy troops in Uruguay and Colombia, grab Hawaii, send troops into Shanghai, trample Taiwan with army boots, throw an expeditionary corps into Korea, land in Egypt and, finally, declare war on Spain and squeeze out of it Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

The cartoons of those years portrayed America as Uncle Sam, who grows from a sweet child into a general dressed in a bowler hat, tailcoat, and striped pants, and then fattens up to the unbelievable proportions of a capitalist clutching a cruiser-battleship under his arm.

Of course, the one that got hit hardest by America's expansion was America itself — more precisely, its Central and South regions. Just look at Panama. The U.S. practically created that country out of thin air. Originally, its territory was part of Colombia. But when Colombia refused to build a shipping canal across the isthmus between the two Americas, a rebellion suddenly broke out in its northern region. Right on cue, the American fleet showed up on the coast. The next day, the U.S. announced that the northern part of Colombia was now a separate country: Panama. And then they went ahead and built the canal themselves. The Panama one.

America hasn’t only gone to war with poor Third World countries; it’s also tried sinking its teeth into some bigger prey.

In 1917, a revolution broke out in the Russian Empire. The Bolsheviks came to power, radical socialists who unleashed mass terror in the country and began preparing for a world revolution. Russia’s allies in World War I — Britain, France, Japan, and others — tried to stop the revolution and sent troops to support what remained of the tsarist army.

Among the Allies were the United States, which landed 12,000 soldiers in Vladivostok and Arkhangelsk. After parading around Vladivostok with flags and getting into a drunken brawl with the Japanese, the Americans soon stopped understanding what they were doing in Russia and went home, having achieved nothing.

It was the only time in history when America and Russia fought each other directly. After that, there has never again been a direct conflict between the two superpowers. Both empires figured out in time that in a direct clash, they could wipe out not only each other, but take the whole planet down with them. So, out of purely peace-loving considerations, the US and Russia decided to fight through their flunkies — small third countries with unstable governments. Political scientists call such wars proxy wars.

All proxy wars follow the same pattern. In some poor country where the government is mired in corruption and couldn’t care less about the population, an opposition starts to form. And it’s far from always being liberal — usually it’s more like pitchfork-wielding workers and peasants. Then Country A steps in and supports the rebels, supplying them with weapons, and Country B steps in to support the current regime, also supplying it with weapons. In the end, a civil war breaks out in the poor country and tears it in half.

Korea and Vietnam are the two most famous proxy wars. The USSR supported the Korean and Vietnamese communists, who fought against local strongmen and promised the people freedom and land. The United States defended the countries’ governments and tried to preserve the old order. As a result, both countries were torn in half. North Korea turned into the planet’s leading totalitarian cult, while South Korea was successfully defended and turned into a cutting-edge country. Vietnam was less lucky. The communists from the North eventually drove the Americans out of the South, but just ten years later, the communist regime in the country collapsed. Today, the country is doing generally fine.

Both wars are vivid illustrations of how the road to hell can be paved with good intentions. North Korea is a phenomenal failure of the USSR and a museum exhibit of the consequences of communism. Vietnam is the gold standard for the monstrous failures of mindless interference. The war in Vietnam not only claimed hundreds of thousands of civilian lives. The Americans used scorched-earth tactics in Vietnam, burning villages with flamethrowers and destroying forests and crops by spraying dangerous herbicides. As a result of the use of chemicals in Vietnam, about a million people were affected, and 150,000 children were born with deformities.

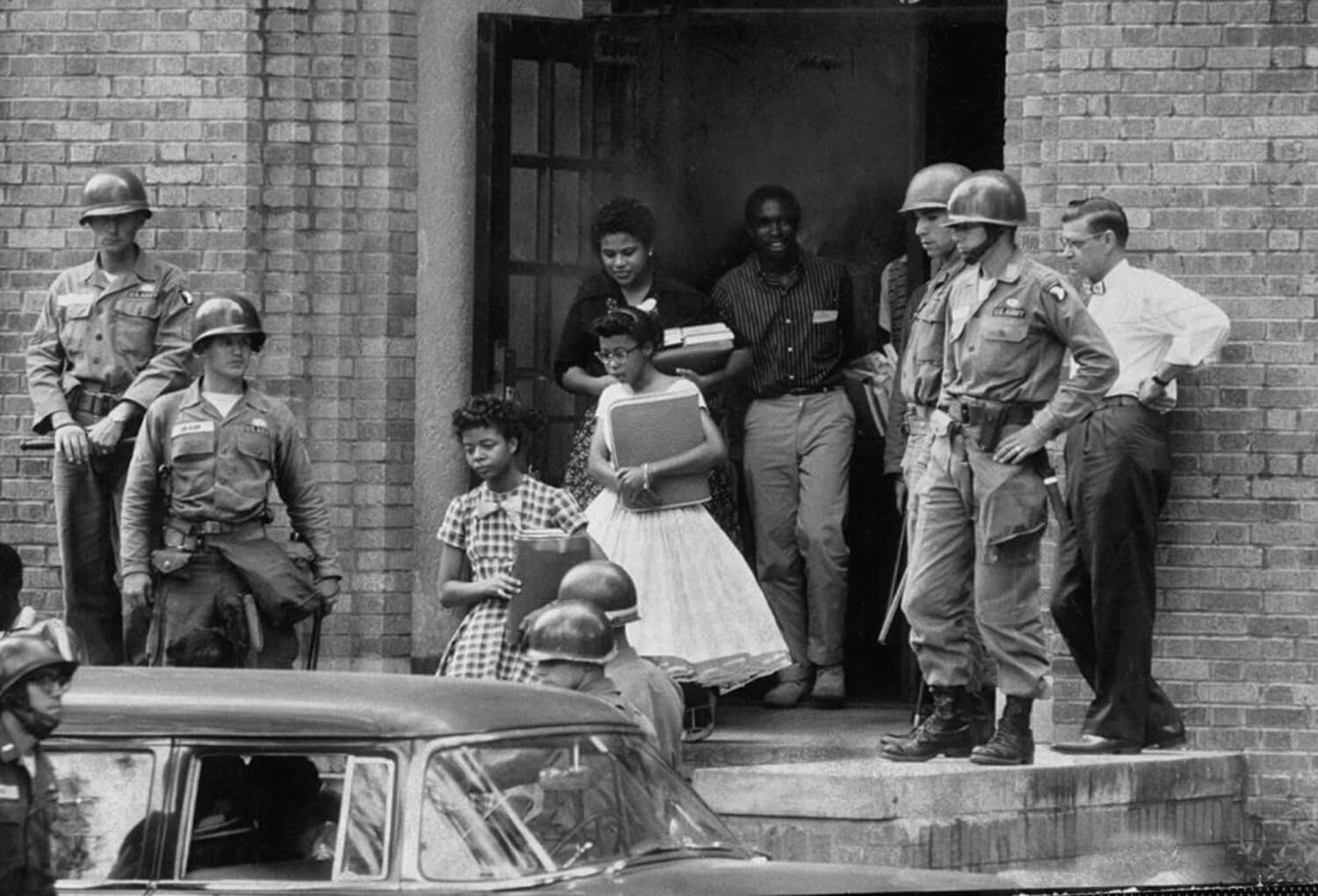

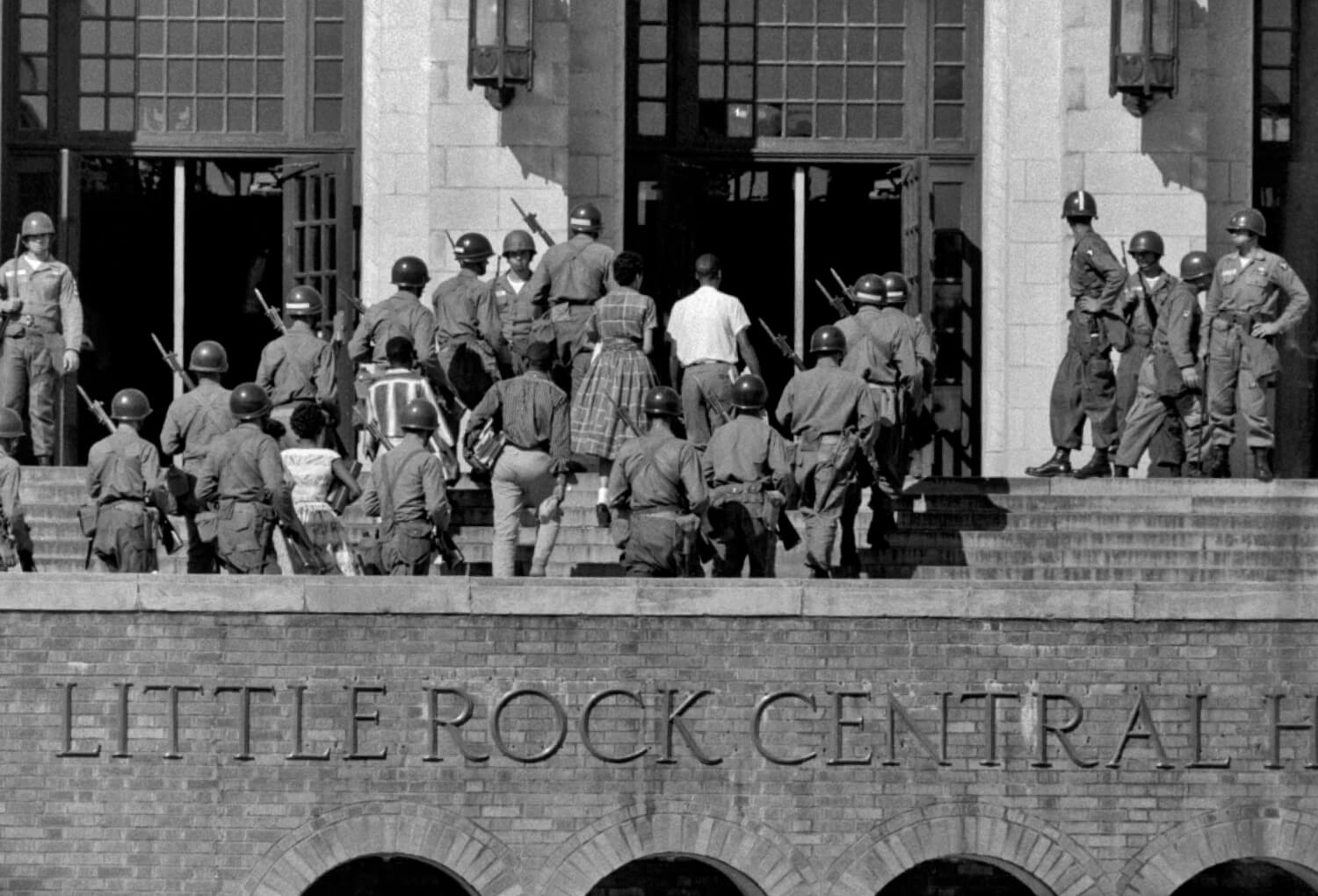

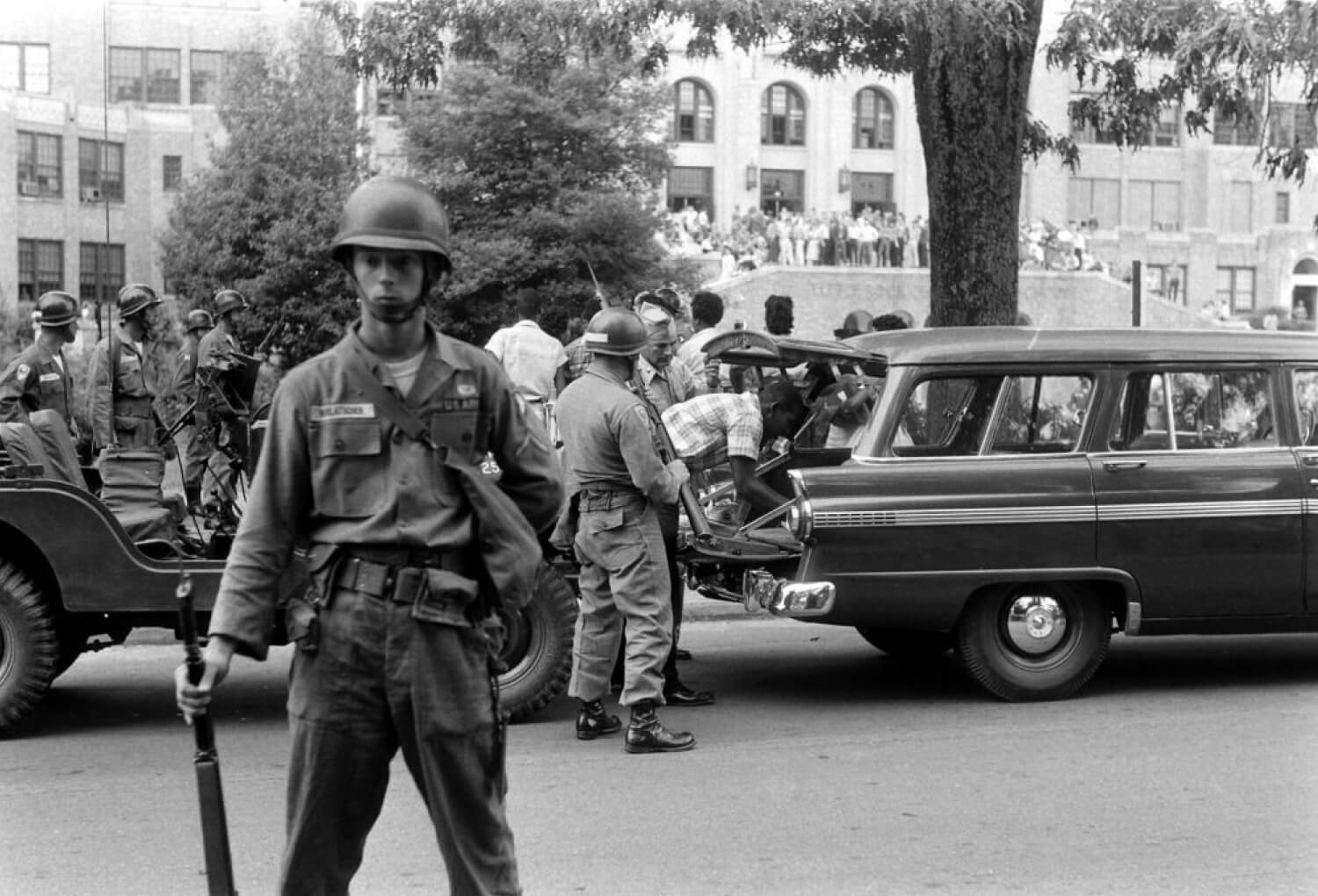

The saddest part is that at that time America itself had barely crawled out of the Middle Ages. It had been only ten years since the Supreme Court struck down segregated schools for black and white students.

The Southern states resisted desegregation so fiercely that the national army had to be brought in. Governors refused to obey, crowds were screaming in the streets, and black children were escorted to school by National Guard soldiers with rifles at the ready.

The Vietnam War became a disgrace for the United States for decades. The whole world, including Americans themselves, ended up with two questions. First: how can a country that only yesterday got rid of racism presume to teach anyone about freedom and democracy? And second: is there really no recourse against America?

The second question was tackled by Bertrand Russell, the very same mathematician who discovered the invisible teapot flying in orbit around the Sun. He organized a tribunal against the United States, modeled on the Nuremberg Tribunal for Nazi Germany. The Russell Tribunal was held in Stockholm and found the U.S. government guilty of genocide against the Vietnamese people.

Unfortunately, the Russell Tribunal had no legal force. But even if it had, holding the U.S. accountable would have been impossible. America is a global hegemon that does not recognize the decisions of the International Court of Justice and has the power to veto any UN Security Council resolution. Imposing sanctions on the U.S. is also impossible: you might as well try to ban Mark Zuckerberg from Facebook. There is no external power in the world, and there never has been, that could hold America to account. Sadly, there’s no recourse against hegemons.

But where justice ends, revenge begins. The absence of recourse breeds terrorism.

In August 1990, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded the small neighboring state of Kuwait, declaring it a historic part of Iraq. Saudi Arabia called on the United States to intervene, and this time the U.S. did everything by the book, securing a UN Security Council resolution. Kuwait was liberated in just a month and a half; the Iraqi troops ran back to Iraq, and Hussein was kindly allowed to stay in power.

These events went down in history as the Persian Gulf War. After the war, Saudi Arabia offered the United States the chance to station American military bases on its territory, since it had itself begun to fear Iraqi aggression. Naturally, America agreed. At first glance, it might seem like an absolutely spotless story. The military operation had UN approval, and the bases were established by mutual consent and for a specific purpose. However, not everyone saw it that way.

The son of a Saudi billionaire named Osama bin Laden thought otherwise. For him, the presence of American troops on the land of the Prophet Muhammad was not a defensive alliance but a desecration of holy ground. Bin Laden declared that the Saudi royal family had betrayed Islam and handed his homeland over to the American infidels.

Osama bin Laden accused the United States of supporting Israeli aggression against Palestine and of committing war crimes in Iraq and Lebanon. He said that America behaves in a way no other power in the world ever has. The deployment of military bases in Saudi Arabia was the last straw for him, after which he declared holy war on the U.S. government.

The rest of the story, the reader already knows.

A month after the September 11 attacks, the United States sent troops into Afghanistan, whose government — the terrorist group Taliban — was sheltering Osama bin Laden. This was a legitimate and understandable response. NATO invoked Article 5 of its charter on collective self-defense. The UN Security Council, in Resolution 1368, recognized the attacks as a threat to peace and affirmed the right to self-defense.

Everything was ruined by another operation. Two years later, after fabricating intelligence data about weapons of mass destruction, America, in the person of President George W. Bush, decided to finish the job and topple the Saddam Hussein they’d failed to take out in the ’90s. In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq — a country that was certainly nasty, but had absolutely nothing to do with either the 9/11 attacks or Al-Qaeda itself.

And the reader knows the rest of this story, too. Ten years after the invasion, out of the wreckage of the Iraqi army and in the midst of a civil war, ISIS was born — a terrorist group so bloodthirsty that even Al-Qaeda disowned it.

The history of America is divided into before and after September 11.

Soon after the attack, Congress passed a law with the wonderfully convoluted title “Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.” For short — PATRIOT. It was a draconian set of measures rushed through with hardly any debate. The PATRIOT Act radically expanded the powers of U.S. intelligence agencies. For example, the FBI gained access to Americans’ bank accounts, phone calls, and correspondence without a court order.

Wiretapping is pretty intangible, though. What really hit everyone was the airport security checks. Before the 9/11 attacks, there was almost no screening when you boarded a plane in the U.S. Nobody made you take off your shoes or pull out your belt. You could bring water, scissors, and even lighters right into the cabin. More than that: friends could walk you all the way to the gate to see you off! Other countries were stricter, but even in Europe, Russia, the Middle East, and Asia, there were neither body scanners nor thorough baggage checks.

The madness going on in airports all over the world today is a consequence of Osama bin Laden’s attack and the PATRIOT Act. And this kind of surveillance over citizens is exactly what defines the new empires.

⁂

Like the history of any country, the United States’ history is full of bloody stains. Even taking into account all the war crimes and illegal interventions, it’s nowhere near the scale of the British Empire. And as for the horrors committed by the Russian and Ottoman Empires — don’t even get me started.

Many people love to point at the long list of American invasions and say, “Look how many there are!” And yes, that’s true. The list is long. But it doesn’t just include Iraq and Vietnam. It also includes fighting Libyan pirates in the 19th century, the war against Hitler, a liberated Korea, a saved Kuwait, and terrorists with their nicely rearranged ribs.

Like the history of any country, the history of the United States is full of bloody stains. And yet the number of good deeds America has done far exceeds the amount of misery and destruction it has caused. It plays the role of global policeman badly, but a hundred times better than the USSR or China would have. And there are no other contenders, nor are any expected.

Ivan Aivazovsky. Food distribution during the famine in Russia, 1892