America. Part Three. Tomorrow

American Dream — Home in Texas — Medicine — The Melting Pot — Sluggish Depression — Poor and Rich — America’s Great Divide — Trump

American Dream

For a child who was born and raised in Eastern Europe, American cities always seemed distant and unbelievable, almost like something out of a fairy tale. No wonder, really: the countries of the former Eastern Bloc were mostly built up with identical concrete apartment buildings that looked pretty drab even in summer, and in winter inspired genuine despair.

Of course, in Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and other former Soviet countries, there have always been villages, rural settlements, and pockets of private housing right in the middle of cities. However, the houses there were always run-down, untidy, and even rotting; paved roads were a rarity, toilets were traditionally built outside, and the plots themselves were surrounded by unattractive fences.

All of that paled in comparison with the life Hollywood showed. Any Soviet child, rewatching Back to the Future for the hundredth time, dreamed of living there — in a spacious two-story house with a white porch, standing on an endless straight street lined on both sides with lush elms and stretching so far into the distance that its end became indistinguishable behind clusters of yellow traffic lights hanging overhead.

And had to live here — in a standard apartment with a rug on the wall, in a standard stairwell with the inescapable smell of the trash chute and damp, in a standard building of the standard series П-44.

The construction of housing in the Soviet Union was overseen by the state bureau Gosstroy — literally, Govbuild. The engineers at Gosstroy did not simply build cities the way commercial companies do today; they also defined construction standards. These standards were an attempt to strike a balance between housing costs and human needs, to quickly cover the entire country with affordable yet decent housing.

Back in the 1950s, Gosstroy developed a highly original plan for building cities with socialist housing. Taking as a basis the ideas of the French architect Le Corbusier, who proposed constructing buildings in the middle of a park, Soviet urban planners invented the microdistrict development model.

They proposed building cities according to a molecular model: individual houses (electrons) were grouped into residential clusters (atoms), which in turn were combined into neighborhoods (molecules). Here’s how the plan was made. First, on a drafting paper, the future school was drawn. Then a compass needle was stuck into the center of the school, and a circle with a radius of 600 meters was drawn around it. Next, the same operation was carried out with the kindergarten and the public park, around which circles with radii of 300 and 400 meters were drawn. A series of such constructions defined the microdistrict’s boundaries.

Soviet urban development was far from thoughtless: all the shops, schools, parks, pharmacies, bus stops, and kindergartens ended up within walking distance. The problem was that the very idea of dense communal living turned out to be a failure. People were settled in tall apartment blocks that, with each new government, became ever taller and ever more crowded. The culmination of this story was the near-uniform development of the entire country with identical buildings up to 40 stories high and with a dozen entrances. This already happened in modern Russia, where such buildings are now sarcastically called humanhills.

American cities are organized quite differently. Skyscrapers stand only in the business center of a large city — the downtown. Beyond that, America is usually built up with two-story or one-story houses. Naturally, there has never been anything like a Govbuild in the USA — houses have always been built by private companies — and if you ask an ordinary American, “What do you think of Le Corbusier?” they’ll most probably answer, “Not bad, I ate it in France.”

The American otherworld revealed itself to the Soviet people only on the eve of the USSR’s collapse. American films entered the country, freedom of speech emerged, and market reforms began. Looking at America, many people started to wonder: what would Russia look like if we had never had the Gosstroy, and houses had always been built by private companies? Of course, it would look like the American dream! The entire continent would be covered not with gray concrete, but with marvelous private homes!

Alas, the answer many Russians gave themselves turned out not just to be wrong; it was wrong twice. American housing not only has nothing to do with a dream. It has also never been a product of a free market. Although America was indeed built by private companies, the state directly intervened in the market. And the result of this intervention was not picturesque villages, but enormous megacities and suburbs stretched to the limit, which today are literally collapsing under their own weight.

The American Dream, as the classics understand it, was born right after the Second World War. When millions of American servicemen began returning from the front and the army as a whole, the government began generously handing out subsidies for education and housing. Naturally, paying for housing in city centers would have been far too expensive, and the cities weren’t limitless. So the subsidies were given for building houses in the suburbs, where vacant land was being handed out for next to nothing.

During the period when subsidies were in effect, more than 4 million families received subsidized housing. When every war veteran in Europe had a home of their own, new wars began — first in Korea, then in Vietnam. At that point, another 9 million families received housing. Later, subsidies began to be granted simply for military service, and by then new wars had come along: in Iraq, Serbia, and Afghanistan. In this way, 29 million American families obtained their own homes at bargain prices, and a house of one’s own, a car, and a happy family came to be known as “the American Dream.”

In this utopia, everything would be perfect if not for one circumstance.

The development of suburbs led to an explosive increase in the area of cities. While European cities grew not outward but inward — with an increase in the number of details and a complication of street layouts — American cities were simply bursting in all directions with a monotonous rectangular grid. The city centers, by contrast, began to decline as Americans moved en masse to the suburbs. Maintaining these increasingly empty centers became unprofitable, so they either sprouted business districts or simply became deserted.

It turned into yet another American paradox. While cities around the world were growing and developing, in the US, cities were living in the past and shrinking back into wastelands.

Brainerd, Minnesota. West Front Street in 1894 and 2025

Decline came not only to small towns. Megacities like Chicago, although they did not turn into wastelands, threw an entire layer of history onto the trash heap. Magnificent neoclassical and Art Deco buildings were ruthlessly demolished by bulldozers, and in their place rose glass-and-concrete skyscrapers that have now become the foundation of the American style.

Chicago’s historic architecture was torn down and replaced with skyscrapers

In the suburbs themselves, things turned out even worse. Each new wave of construction subsidies wrapped the cities in yet another ring of identical houses, set ever farther from the center. As a result, today’s American cities have turned into the same kind of humanhills — only horizontal.

Meanwhile, all the businesses stayed put downtown. So, to let people reach the right skyscraper for work, they had to build entire networks of roads and interchanges on a scale the world had previously seen only in dystopian movies.

But even this urban nightmare turned out to be only the tip of the iceberg.

The main problem turned out to be supplying the new districts. As the reader knows, a city is maintained by the taxes collected from its residents. Therefore, under normal circumstances, the settlement of new citizens replenishes the city budget. But taxes grow linearly. If the city keeps expanding, however, the complexity of maintaining infrastructure — power grids, water supply, and sewage — grows much faster, exponentially. It turns out that each new resident not only increases the city’s expenses, but also lives at the expense of the taxes paid by the previous ones... and that is nothing other than a financial pyramid!

And this is not a figure of speech. American cities literally operate on the principle of a financial pyramid.

It was precisely the sprawl of infrastructure that led to the bankruptcy of cities like Detroit, Stockton, San Bernardino, and Chester. And that’s only the official list. Dozens of cities are hiding their default: Cleveland, Baltimore, Camden, Gary, Jackson, Bridgeport, Reading, Flint. Many large cities are in very poor financial condition: Chicago, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Portland, and New York. All of them are still alive only thanks to the money the federal government pours into them as if into a bottomless pit.

Many American cities are doomed to catastrophe. Supporting them is as pointless as propping up a financial pyramid. Sooner or later, they will have to declare bankruptcy, and the earlier that happens, the sooner market forces will correct the imbalance that the government has been creating for 80 years straight.

America faces another problem as well. The departure of successful Americans to the suburbs has left downtown to its fate. Mostly the poor, the unemployed, and simply idlers who couldn’t manage to earn enough for their own home remained living in the city center.

As always, black people got hit especially hard. Although by law the subsidies were supposed to go to all U.S. citizens, in practice, banks simply refused to issue mortgages to black veterans who had served honorably in the army and taken part in the war. And if a black person somehow did manage to get a loan, they would be refused when they tried to buy land. The same story played out with education: although the law promised it to everyone regardless of skin color, universities — especially in the South — were in no hurry to admit black students. As a result, even honest, hard‑working, and educated blacks were left without housing and without education.

Today, any American knows: with the exception of the ghettos, the most dangerous and dirty place in America is the city center. Downtown is always filled with bums, drug addicts, and the unemployed, often black. But capitalism is not to blame for this at all; the blame lies with insane social programs.

Home in Texas

As for the suburbs, even in the most luxurious, wealthy, and clean American village, it’s simply impossible to live. Streets laid out straight as if by a ruler; perfectly trimmed, evergreen lawns; neat houses that look like they came off a movie set... boring to death.

And the problem isn’t that you get tired of perfection. The problem is that it’s a half-hour drive to the nearest decent cafe. The problem is that you can’t walk beyond the settlement, because beyond it lies nothing but wasteland and roads. The problem is that a column of protesters shouting “Freedom for Krakozhia” will never pass under your windows, you’ll never spot a concert poster on a lamppost, and the smell of over-roasted chestnuts will never drift out from around the corner.

The reader has surely heard about the epidemic of depression in the United States. And he has surely heard that depression is a disease of big cities, where skyscrapers block out the sunlight, and the sirens of ambulances and police cars make it impossible to sleep at night.

Oh no, dear reader! Depression reigns supreme in the American heartland, in villages and suburbs. It does not bloom and multiply among skyscrapers, but lives together with Americans in their luxurious, brand‑new houses; depression sleeps with them on Texas King memory‑foam mattresses and accompanies them to work on the back seat of a brand‑new Ford F‑150.

The author spent several months living in the southern states. For me, an outstanding example of a depressing life was Houston, a large city in Texas that houses the Mission Control Center for space flights. A new street called Star Sky Way was polished to a grotesque perfection, and along it stood a neat row of brand‑new houses.

An American lived in one of these houses. Let’s say his name was John. He lived alone, with no family or pets, and worked remotely, apparently as a circuit design engineer for a large company. John decided to rent out one of the rooms in his house on Airbnb — perhaps in order to pay off his mortgage more quickly.

The author turned out to be his first guest. I stumbled into his place, soaked to the bone from the rain, since I’d had the bright idea to take the bus from downtown Houston. When John met me — wet, with an old backpack on my shoulders and speaking with a rough accent — he looked, judging by his face, about ready to call 911. Noticing this, I decided not to wait for his question.

“Oh, sir, I beg your pardon. Allow me to explain my appearance. The thing is, I’m a traveler and have already been to seventy‑five countries. I travel with just a small backpack and use public transport. So I got soaked walking from the bus stop to your house.”

“Got it... Wait, there’s a bus that comes here?”

“Yes, sir. You have good public transport in America, whatever people may say. Not Europe, of course. But believe me, in the rest of the world it’s even worse.”

“Amazing, I live here and didn’t even know there were buses around. But you could at least have called a taxi, why get soaked?..”

“Well, sir... I’m from Russia.”

The house in Texas turned out to be the best one of the whole trip across America. It was new and bright, with an incredibly large living room and kitchen, equipped with the latest appliances. I had never lived in a place like that before.

The hallway lights turned on automatically whenever someone walked through. In the evening, the lights in the living room switched off by themselves, and in the morning they switched back on. At night, the temperature in the house dropped, so it was more comfortable to sleep under a blanket, and by morning, it slowly climbed back to normal.

Behind one of the doors in the living room was a direct exit into the garage, so you could drive to work in the rain without even needing an umbrella. The big TV in the living room was voice-controlled through an Amazon smart speaker. In the same way, you could ask the house to turn on the ceiling fan, dim the lights, or even show who was standing at the front door. And finally, a little pull-cord hanging from the hallway ceiling lowered a hidden ladder that led up to the attic, which, however, was entirely taken up by the air-duct system.

“John, everything you’ve got here in Texas is just insanely huge!”

“Exactly. This isn’t New York with its tiny apartments. In Texas, we like to live big. I used to live in a big city, but it wasn’t the same. In this house, I feel super comfortable.”

“It’s just it’s so far from the city, and nothing much around. In the city, you walk outside, and everything’s right there, and there’s always something going on.”

“Yeah, that’s the upside of cities. But just look at the downsides: traffic jams, homeless people, noise, and crazy rent. And if I need to go into the city, well, I’ve got a car.”

“Don’t you ever get bored out here?”

“Sometimes I do, but then I just hop in the truck and drive over to my friends’. We order pizza and watch football. That’s it.”

The next day, before heading to Houston, I decided to take a walk around the neighborhood. It turned out that the American’s house was one of hundreds of exactly the same beautiful, brand‑new houses lined up along the street.

Closer to the edge of the neighborhood, I came across an overgrown pond, and the landscape suddenly looked just like rural Russia.

The houses around the pond, as well as right at the edge of the village, turned out to be surrounded by a solid wooden fence. And although the neatly trimmed lawns together with the smooth sidewalk indicated that I was still in the United States, there was something in the air that felt inexplicably Russian.

The exit from the settlement was crowned by large automatic gates, beyond which stood the very same bus stop where the author had pulled in yesterday. That’s exactly where the polished sidewalk ended. Beyond that, running along the highway, lay a narrow, purely technical pedestrian strip leading to nowhere.

Looking at the map, I found several restaurants in the area with incredible names like “Take the Wheel” and “Mad Max BBQ,” where no sane person would ever go for dinner. There were also a couple of food markets of dubious quality. Other than that, the place was surrounded by the standard American set of entertainments: a church, a school, a daycare, a soccer field, and a pickleball center — an idiotic mix of tennis and ping-pong for retirees.

You could still walk to the small stores, but the nearest Walmart, the most famous American supermarket, turned out to be either a two-hour walk, a twenty-dollar taxi ride, or forty minutes by bus. Getting to downtown Houston by bus took even more — an hour and a half.

Within just a week, living in the Texas house became unbearable. The American himself worked from his home office from morning till evening, and at night drove off to see his friends. The author, bored out of his mind, explored the house and discovered a door leading to the backyard. It turned out to be just as far from the American Dream as the American Dream itself. It was a small, empty, and fully fenced-off nook, cluttered with patio furniture and a barbecue grill. The heat — the unbelievable, suffocating Texas summer heat — made it impossible to stay there. But even without the heat, the place just felt uncomfortable.

Looking even more closely, I discovered that the windows didn’t face a cozy little garden at all. Carefully hidden behind the blinds, there was... the wall of the neighboring building. Exactly the same.

John’s house wasn’t the first place in Texas where the author had lived. A week earlier, I’d stayed in a suburb of San Antonio — a pretty nice little town with a gorgeous riverwalk right in downtown. That time, I got the classic one-story America. Same twenty-minute drive from a major city, but a completely different picture!

The house was built in 1980. What can I say — practically an old-timer! Naturally, the inside couldn’t possibly feel as bright and spacious. The ceiling hung low like a heavy sky, and the windows let in light only reluctantly, leaving the rooms in a rather dim gloom.

Still, even in this well-aged house, there was a wall-mounted control panel that managed the temperature and the lights. Mechanical thermostats first appeared in American homes back in the 1930s, so you can’t impress even a resident of the most remote backwater in the U.S. with a “smart home.”

Alas, the backyard at this house also turned out to be a lifeless, overgrown wasteland. Texas is one of the hottest states, so it’s hard to find anything in a backyard besides sun-scorched grass.

The surrounding houses were nowhere near as cool as those in Houston, but at least they were different. The street was just as scruffy, but it actually showed signs of life. The mailman was delivering letters, the ice cream guy was cruising past the houses in his musical truck, and the residents were tidying up their lawns. Just like in proper small-town America, passersby greeted the unknown newcomer with a fleeting smile and the standard question: “Hi, how are you?”

On one side of the street ran a concrete sidewalk, another typical American feature. Every now and then, it would stop for no apparent reason, then start up again.

Unwinding like a meander from hidden nooks toward the edge of the settlement, the sidewalk eventually led to a bus stop, from which you could either get to downtown San Antonio or ride to the nearest Walmart. The scenery around the stop once again brought Russia to mind and made it pretty clear that only poor folks and retirees ever used it.

The author got on a bus, took a random route, and got off the moment he saw something unusual out the window. What caught his eye was a crooked Presbyterian church that looked more like an electrical utility box in Balashikha.

The church was surrounded by one-story houses that were anything but cozy this time — ramshackle to the point of rivaling some Siberian village.

The manicured lawns were long gone. Instead of the curly elms along the streets, there were thickets of maple and the chewed-off stumps of some other trees.

Although all the roads were paved, the view was anything but uplifting: a cracked road stretching off to god knows where, crooked houses, and wooden poles from Roosevelt’s time leaning off to the side.

Finally, between the two parts of the settlement, I found a railroad and a power line ran alongside it. A lonely rusty track shot straight off far beyond the horizon, and along the rails there was trash, torn clothing, and wooden boards from which someone had vainly tried to knock together a shack.

The Texas House has taken the issue of the large number of mental disorders in the U.S. off the table.

An American, whether he lives in an old one-story house or a brand-new Texas palace, is a hostage of the American Dream. He’s isolated from society, shut in on that little patch of land in front of his house, stewing in his own juices and cooking up a nice case of depression. Of course, that’s not the only reason, but it’s definitely the most striking one.

Medicine

If owning your own home, a car, and a happy family is called the American Dream, then healthcare ought to be called the American Tragedy.

And here we are again with this American paradox. On the one hand, the U.S. has the most advanced medicine in the world. They use surgical robots, transplant organs, treat cancer, and implant chips. At the same time, clinics slap on astronomical bills for popping a pimple, nurses are googling drug names, and a dentist’s office in Brooklyn looks as if they just finished filming “Saw 20” in there.

“Because it’s private!” immediately reminds the reader.

“About as ‘private’ as housing,” the author shoots back.

In reality, healthcare in the U.S. is not only not private but also, in many ways free. And that’s exactly where all the horrors come from. It should be made private and price regulation abolished... But let’s take it step by step.

The gigantic medical bills result from the lack of private healthcare in the U.S.

Free healthcare was invented in the Soviet Union. Before the Russians, the Germans had made huge progress, but their system introduced by Bismarck in 1883 was still insurance-based, not free. The outstanding physician Nikolai Semashko was the first to create a direct, state-run, completely free medical system with no insurance at all, turning treatment from a service into a human right.

Meanwhile, nothing in this world is actually free. Behind any service, there’s labor that has to be paid for — the only question is how, and by whom. The USSR took it upon itself to provide free healthcare, education, and housing to two hundred million people. To cover costs on that scale, all private businesses had to be handed over to the state, and its profits were then siphoned into the budget, from which those “free” services were paid for.

The upside of this system was universal access to healthcare and the complete absence of billionaires. The downside was the gradual economic erosion. Directors’ salaries barely depended on how well they did their jobs, so they just kept their seats warm, and investing in new developments became extremely difficult and risky, since any failure could easily be taken for theft.

The USSR collapsed and was replaced by capitalist Russia. Business was privatized, and now the budget could only collect taxes, not all the profits. To save the bleeding‑dry budget, Russia introduced a health insurance tax, and to preserve the illusion that healthcare was still free, they decided not to show this tax in payroll calculations. This trick, which falls under the category of fiscal illusions, leads people to believe that their healthcare is paid for by their employer.

European healthcare works about the same way. The tax rate varies. While in Russia they pay 5.1%, in Germany it’s almost 15%, in France 13%, and in Italy 9%. This means that with a $2000 salary, a Russian pays $102 for insurance, a German $300, a French $260, and an Italian $180 per month.

There’s private healthcare in Europe too. It’s especially popular in Russia, where there are always lines in the free clinics, and the small regional hospitals look downright terrifying. The main problem with this “dual” healthcare system is that even if someone only goes to a private doctor, they still have to pay a tax out of every paycheck. So they’re basically paying for an imposed service. Normally, that would be something you could take to court — just not when it’s the state doing it.

Regional hospitals in Russia can be in terrible condition

The tempting idea of free healthcare was bound to find its way into the heads of American socialists. It was first proposed back in the 1920s, but it didn’t reach the halls of power until 1965. The Democratic Party was then pushing for a European-style welfare state and suggested starting with healthcare reform. The Republicans sharply criticized the reform and warned that it would lead to a wild surge in prices.

After Kennedy’s assassination, all the power in America was in the hands of the Democrats, so the universal healthcare project was passed without much trouble. It consisted of two programs: Medicare and Medicaid. The first one set super-low prices for medical treatment for seniors over 65, and the second introduced free healthcare for low-income people. To pay for these programs, they introduced a 2.9% payroll tax. They’re still in operation today, in 2025.

The law that was passed was a huge success. Millions of Americans gained access to socialized medicine. The hospitals remained private: a person would come in, get treated for free or for a modest fee, and then the hospital would be reimbursed by the government. The law defined the reimbursement amount as reasonable. In practice, it was calculated as the lowest of the following: the average price in the area, the doctor’s usual price, or the actual cost of the service.

The prices were set too low from the very beginning, but the Ministry of Health assured hospitals they’d make it all back once millions of new clients came rushing in for treatment. And they did rush in. In the first year, 19 million Americans who had basically never gone to the doctor before, signed up for the program. Hospitals were hit with such a flood of patients that they ran out of beds and doctors.

For the first few years, the system coped, but then it started to break down. Demand for medical care shot up many times over, but prices, of course, stayed the same! To stay afloat, hospitals tried to get around the government’s artificially low rates. They started jacking up the “reasonable cost” any way they could: adding unnecessary procedures, inflating production costs, padding reports, and so on. Large hospitals still somehow managed to maneuver, but small rural clinics began shutting down en masse.

The introduction of state-run healthcare led to the mass closure of hospitals

The Ministry of Health was frantically looking for ways to plug the hole in the ship. They introduced spending controls, reimbursement quotas, and strict reporting. None of it helped much. Hospitals were shutting down, and Medicare was just devouring the budget: from 1970 to 1985, expenses shot up from $7 to $72 billion.

Finally, the Ministry of Health went to extremes, drawing up a price list for every medical service. It contained thousands of entries. Every procedure, surgery, exam, and test was on that list. Only, instead of actual prices, there were work-hours, which were then multiplied by a regional coefficient and converted to dollars. From that moment on, healthcare in the U.S. switched to a stripped-down version of a planned economy. Prices for medical services stopped being market-based and became government-set.

The work-hour table used to calculate the cost of medical services in the U.S.

And to stop hospitals from piling on unnecessary procedures, the government began reimbursing expenses not item by item but as a single flat rate per diagnosis, with a specific bundle of services. Take, for example, chronic bowel backup. Before the reform, Medicare set only the prices of lab tests and a packet of laxatives, while everything else was paid to the hospital at “reasonable cost.” Now, however, there was a single fixed price for the entire treatment: the tests, the laxatives, a week of bed occupancy, the cost of cleaning the bathroom, a gallon of peach jelly, and a gift set of enemas.

The brilliant plan was dreamed up by Republican Reagan, who, back in the 1960s, was busy criticizing the whole idea of socialized medicine. Despite their disagreements, both parties work together just fine. If the Democrats built a coffin for healthcare, the Republicans nailed the lid shut.

Yes, hospitals could no longer extract inflated reimbursements from Medicare. But they had survived precisely by inflating them, because all those work-hour calculations produced completely inadequate prices. The government forced hospitals to operate at an underpriced rate and prevented them from refusing patients. After Reagan’s reform, hospitals began closing by the hundreds each year; many others were on the verge of bankruptcy.

However, even in this draconian system, a loophole was found. The thing is, Medicare, just as before, applied only to seniors over 65. And the law said nothing about the young and healthy! Hospitals had to treat retirees at a loss, but for everyone else, they were free to set any prices they wanted.

A record of Reagan’s speech against free healthcare

American healthcare was saved from collapse by an astonishingly brazen workaround — the kind of scheme worthy of a chapter in an economics textbook.

Suppose treating a senior costs $1,000, of which the government reimburses only $900, and the remaining $100 become the hospital’s loss. Then, if a hospital treats 100 seniors, the total loss will be $10,000. Now, suppose treating a young person costs $100, and the hospital treats 20 young patients in total. Then the revenue from them will be only $2,000, which is nowhere near enough to cover the losses from treating the elderly.

So how do you cover the remaining loss — and even turn a profit? Very simple. You just spread this amount across all the young patients by billing them not $100, but, say, $1,000. They’re the ones who end up covering the losses from treating the seniors!

That’s where those insane bills for tens of thousands of dollars come from. If healthcare in America were truly private, it would never have such distortions. Those crazy bills weren’t created by capitalism at all, but precisely by social reforms and government interference in the economy.

But how on earth do Americans survive with such expensive healthcare? Do they really pay tens of thousands of dollars to treat a common cold? Of course not. Those prices are a fiction. Nobody pays them. And it’s not about insurance.

Gradually, the medical business realized that jacking up bills could not only cover losses, but also turn a nice profit. Hospitals decided, “What’s the difference? We’re already sending out fake bills. Why not make them even faker?” And they literally started making up prices for services the way they liked it. Moreover, different patients get completely different prices! Of course, that’s illegal on paper, but in practice, the cost of treatment is determined by:

- – Type of insurance. Premium plan? More expensive!

- – Medical history. Get sick often? More expensive!

- – Employer. Work in tech? More expensive!

- – Address. From Manhattan? More expensive!

- – Language and accent. Immigrant? More expensive!

- – Appearance. Wearing a suit? More expensive!

- – Companion. Came with a lawyer?.. Cheaper!

“But this is some kind of bazaar!!!” exclaims the reader.

“We did warn you,” reply the economists.

But, as I already said, these bills are a fiction. Under U.S. law, medical debt is not a criminal debt. You don’t go to jail for not paying it. And the hospital won’t go to court, because any judge, when they see a $100,000 bill for popping a pimple, will at best make the patient pay ten bucks, while the hospital could end up in serious trouble.

Medicine in the US is basically an Arab bazaar scaled up to an entire country. Just like a Turkish shopkeeper, the hospital pulls a price out of thin air — about 10 times higher than normal — in the hope that some sucker will actually pay it. Any reader who’s ever been to an Arab bazaar knows exactly what to say to get a discount. The author has counted three options:

- Oh my God, where am I supposed to get that kind of money? — will give 50% off.

- Are you out of your mind, you greedy capitalists?! — will give 75% off.

- I ain’t care I’m unemployed — will ask you to tip the cashier some $50.

The numbers are, of course, arbitrary, but I stand by the meaning.

Actually, it’s even simpler. All the problems with healthcare are solved by getting a good job. Any large company pays for employees’ insurance, and all that haggling straight out of an Arab bazaar is handled by the insurance company. The person themselves pays the remaining couple of dozen dollars. No good job? Then you’ll have to wait your turn at a low-income clinic, where treatment is free. In the northern states, there are plenty of them; in the southern ones, fewer, but overall, only 8% of the population in the country lives without insurance.

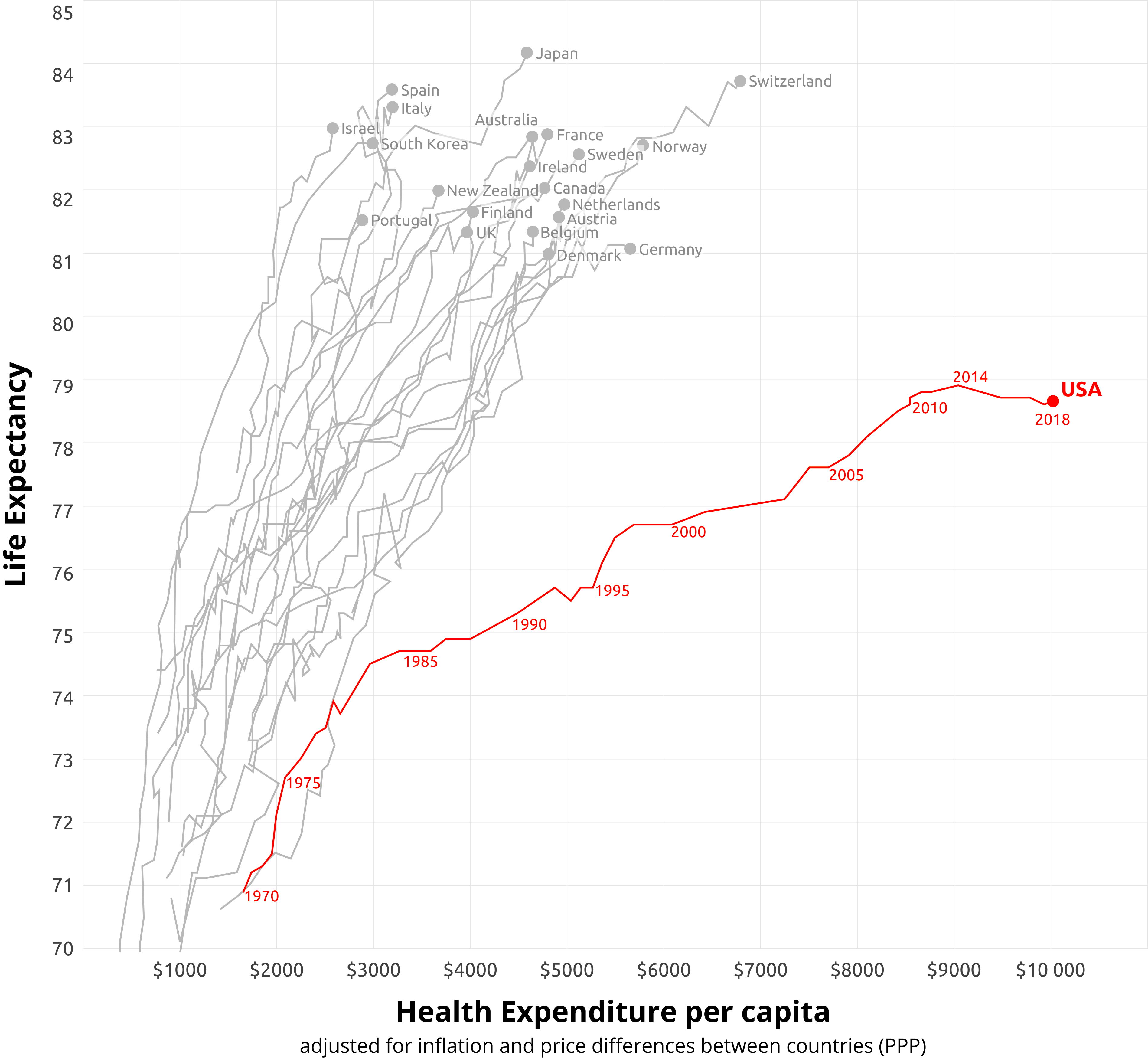

The quality of healthcare is measured by life expectancy. And on any chart, America is way out in front on healthcare spending, but when it comes to life expectancy, it lags behind all other developed countries.

The chart looks terrifying, but that’s just the lines and a cleverly chosen scale. If you look at the actual numbers, people in Europe live to 82, and in the US, just under 79. A 3-year difference isn’t that big. For example, in Russia, people only live to 70 — now that’s a real difference.

But what’s dragging America down isn’t bad healthcare; it’s the countryside. There’s nothing in Europe quite like the American backcountry, where it’s just ranches for dozens of miles in every direction. In major U.S. cities, people live on average just as long as in Europe. New York or Austin, with their 82.6 years, beat Berlin by a full year of life, and in some cities, people live up to 84 years.

It seems like rural hospitals were hit the hardest after socialized medicine was rolled out, right?

Despite failures, American socialists have been calling for completely free European-style healthcare for decades. The first to respond to their call was Barack Obama, who passed a law with the cute name “Obamacare.” Stripping away all the fluff, the law simply required every American to buy some kind of health insurance, even the cheapest one, and if you refused, you faced a fine of up to $700 or 2.5% of your annual income. The poor, as usual, got subsidies.

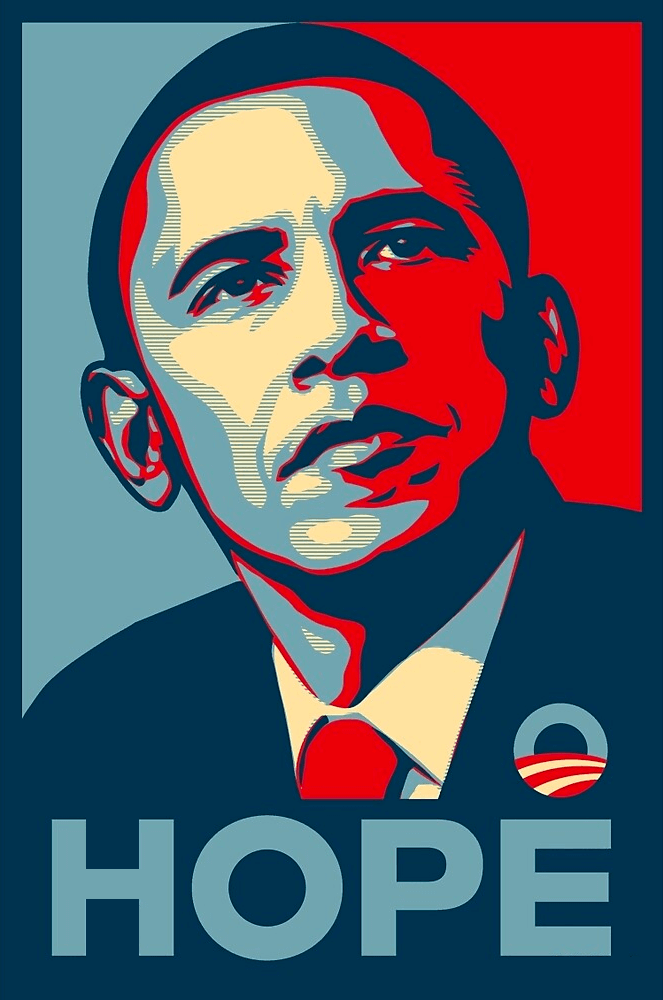

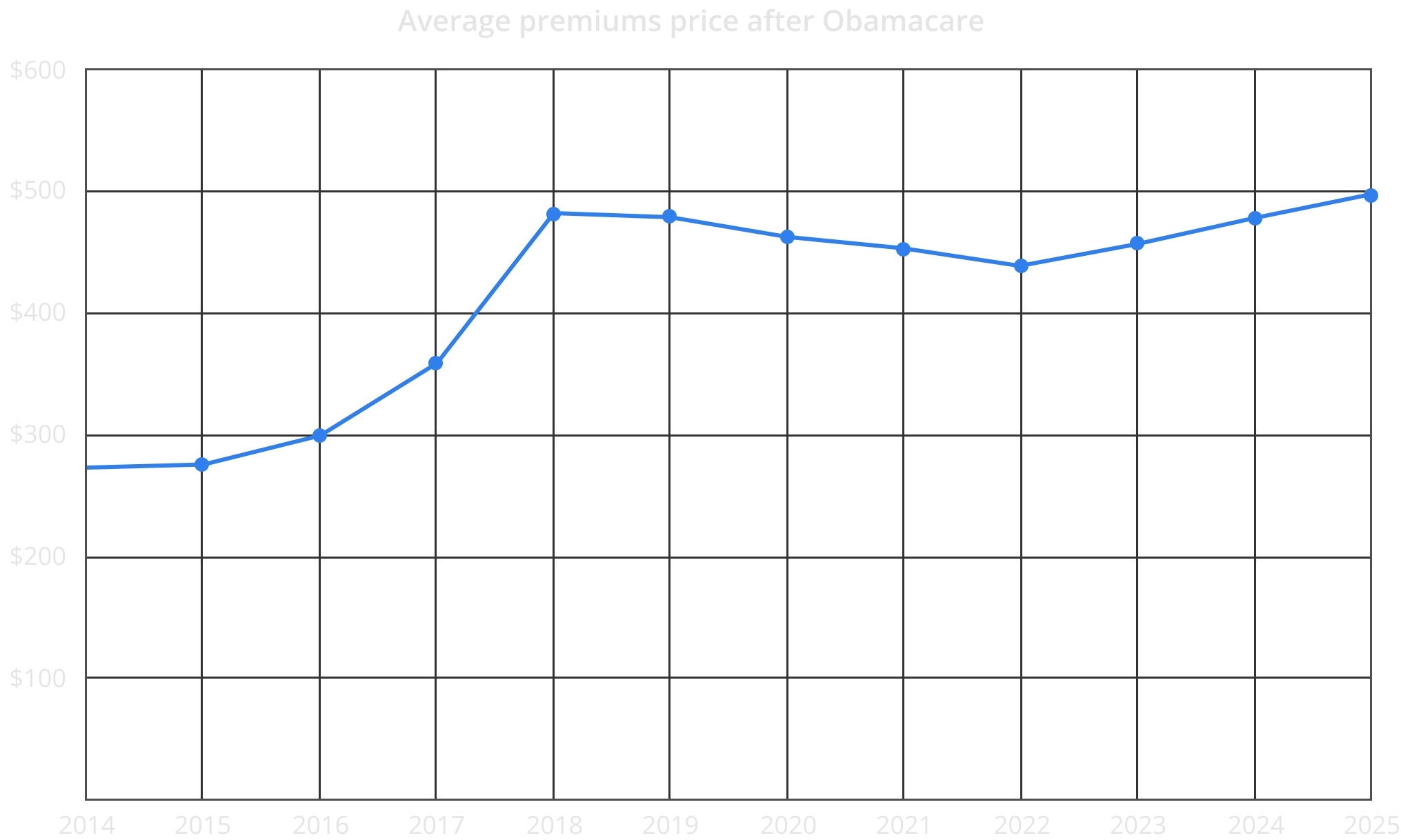

What could possibly go wrong with Obama’s plan? Literally everything. Obamacare went into effect in 2014. Millions of Americans rushed to buy insurance and, in full accordance with the economics textbook, medical costs shot through the roof. Before Obama, the average insurance plan cost $250 a month; afterward, it was around $500. At that price, far from everyone could afford it — and on top of that, there was a penalty waiting for them!

Obama’s half-baked program didn’t last long. By 2018, the Republican Trump had become president. With a one-vote margin, Congress decided not to repeal Obamacare, but to make it optional. After that, insurance prices went down and then returned to their usual rate of growth.

The reader is probably starting to wonder: so how does healthcare work in Europe or Canada then? Answer: It doesn’t.

Germany takes 14.6% as a health insurance tax. On top of that comes a generous 2.5% insurance company fee and a “penalty” of up to 4.2% for not having children. Total: 21.3%. With an average salary of €4,500, that means a German pays €945, or about $1,100, every month for insurance. In the U.S., that kind of money buys you a gold-level plan from Anthem — one of the best on the market.

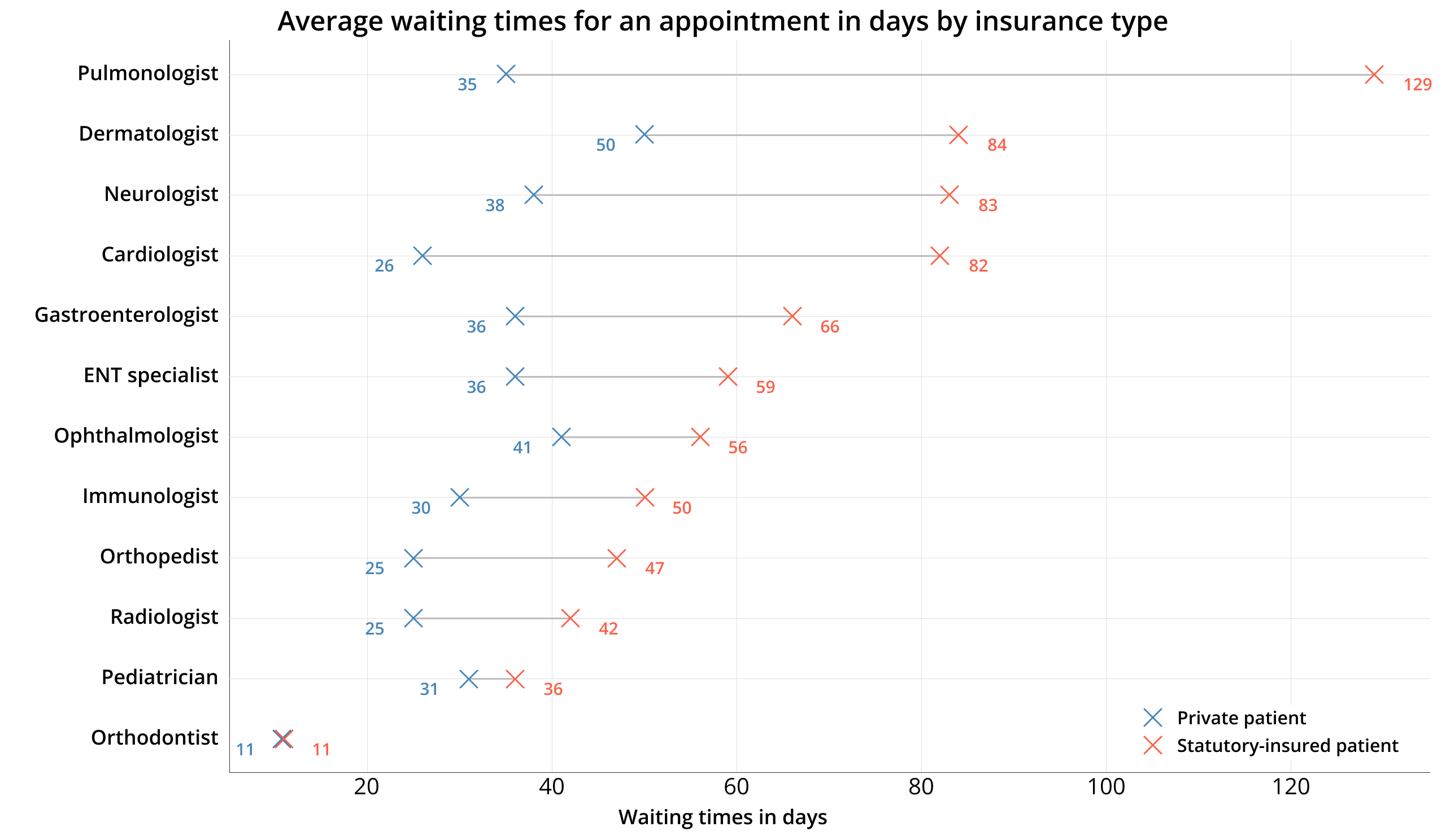

Maybe Germans get much higher-quality services for that kind of money than Americans do? Alas, no. Universal insurance has brought Germany’s medical system to a standstill. Germans wait for a doctor’s appointment for months. To see a cardiologist in 2025, you have to wait 82 days. For an eye exam, the wait time is 56 days. Even patients with extended private insurance have to wait about a month in line.

Waiting times to see a doctor in Germany, 2025

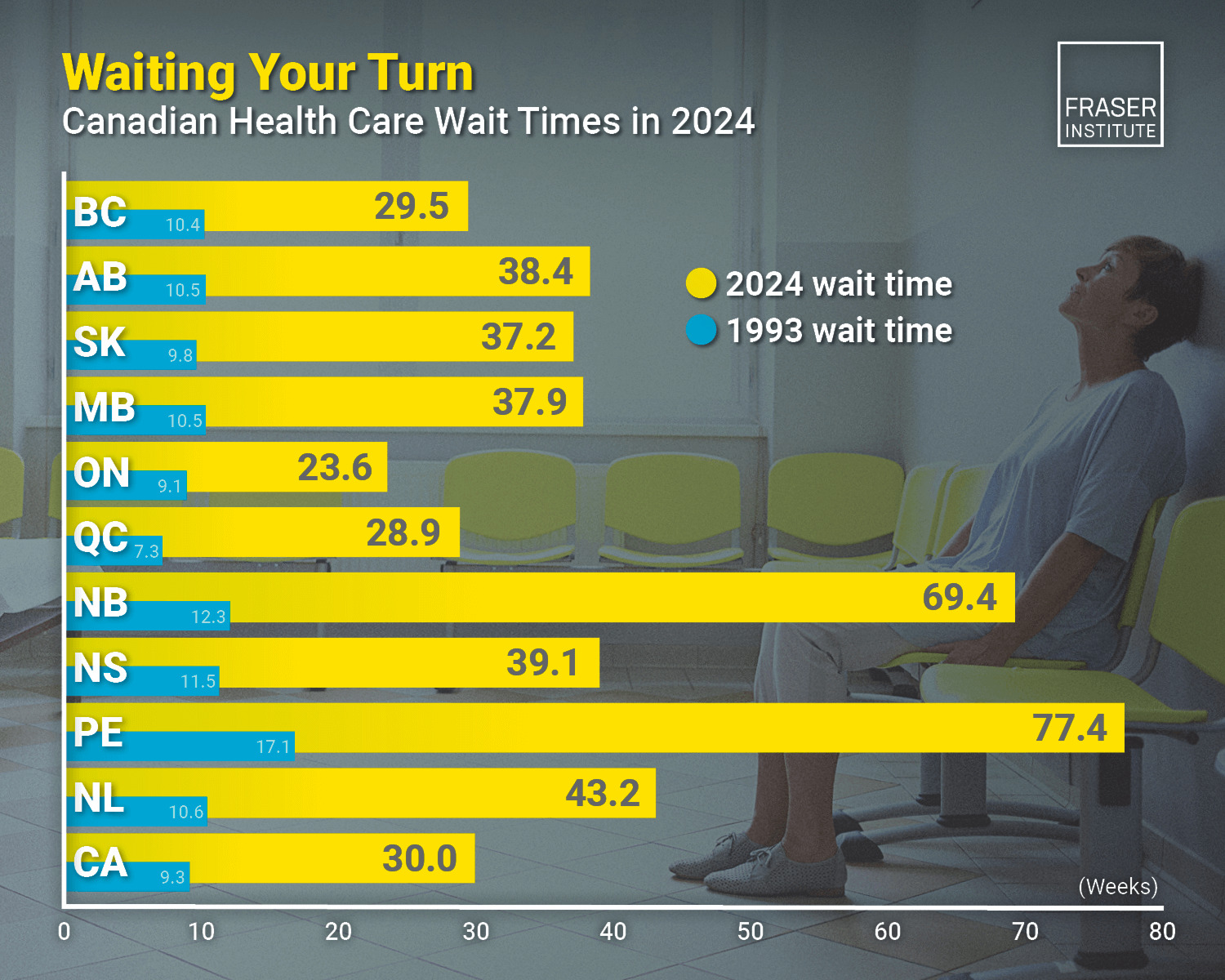

There are lines in other countries, too. Every year, they just keep getting longer, since the government keeps rolling out new “free” services. If in 1993 the wait to see a doctor in Canada was 10 weeks, then in 2024 Canadians wait 30 weeks — almost 8 months! Unfortunately, you can’t see these lines in photos because, in our age, everything has gone electronic.

Waiting times to see a doctor in Canada, 2024

Any country that tries to cheat the laws of the free market is headed for the same fate. Modern economists like Piketty, Krugman, Guriev, and Stiglitz pass off long-obsolete ideas as some kind of new approach to economics. The only thing that sets them apart from their 20th-century colleagues is that they use models and big data.

However, the economy is a chaotic system. It fits into models about as well as wind currents in the atmosphere. Perhaps before tackling the economy, Mr. Piketty should try his hand as a weather forecaster and attempt to control the weather — or at least predict it for more than two weeks.

If America keeps heading down the path of universal free healthcare, its medical system is in for an even bigger collapse than in Europe. On the other hand, repealing Medicare will cause yet another split in society, one that’s hardly going to be smoothed over by scrapping a tiny 2.9% tax. So what’s to be done?

Fortunately, in the U.S., there’s plenty of room to maneuver.

Today, strict quotas are in effect in 35 states. Not only is the number of hospitals limited, but also the number of beds, machines, ambulances, and even operating tables. The quotas were introduced back in the 1970s so that “extra hospitals” wouldn’t suck the budget dry. Because of these quotas, in America, you can’t just go and open a new hospital. You can’t even expand an old one.

To open a hospital, you need to get a “Certificate of Need.” It’s issued by each state’s Department of Health. There’s a board of bureaucrats that you have to convince that there aren’t enough hospitals in a given county and that a new one is absolutely essential. Naturally, the board includes the directors of the hospitals that are already operating, so convincing them is impossible.

That’s why private clinics are so popular in America. Usually they’re opened in a standard single-family house or on the first floor of an apartment building, with a movie-style sign hung out front: “Dr. Brown.” There can’t be any hospital beds, operating rooms, or ambulances in places like that, so no certificate is required to open one. What you do need is a medical degree and a state license.

Getting a medical degree in America is insanely hard. Education costs $350,000, and competition can reach 12 applicants per spot. And it’s not about education being paid. Back in 1908, there were 155 medical schools in the U.S., which fully covered the demand for doctors. Then, a reform introduced strict accreditation rules that, by 1930, left only 76 schools in the entire country. Today, there are about 160 medical schools in America — about as many as there were more than a hundred years ago — but the population has tripled.

The shortage of doctors could easily be addressed by migrants from Europe, Russia, and China, who train excellent specialists. However, all these specialists have to study all over again for 3–7 years in America and retake the exams! Even if a doctor has worked for 20 years in neighboring Canada, they can’t just come to the U.S., have their degree recognized, and start working!

American healthcare is anything but private. It’s socialized medicine with tiny specks of market thrown in. Without broad market reforms, it’ll keep looking like an Arab bazaar. Accreditation standards for medical schools need to be loosened, caps on opening new hospitals lifted, and foreign doctors’ diplomas recognized as equivalent to American ones.

The Melting Pot

Despite all the tricks the U.S. pulls on immigrants and tourists, the way people are treated inside the country is exceptional.

First of all, in America, nobody looks at your passport. You’d think: what could be simpler? Alas, these days that’s a real rarity. The author’s origin is Russia, and in the year my country started the war with Ukraine, I travelled through 30 countries before I reached America. In each country, people reacted differently to my passport. In some parts of Europe, it drew a barely noticeable smirk, while in the Middle East and Africa, on the contrary, it inspired excitement and respect.

Anyway, it wasn’t all that important what kind of reaction my passport provoked; what mattered was that it provoked one. Only in America was there no reaction at all. None. Neither bad nor good. Zero!

It wasn’t just about hotels. Eventually, it came down to my first account at an American bank. I was all excited, having heard so much about the discrimination reigning in European banks. Even today, three years after the war began, they still refuse to open accounts for Russians who legally live and work in an EU country.

Although America hadn’t sunk to that level of disgrace, I was prepared, if not for an outright refusal, then at least for some questions. So I came to the bank, put my passport on the table, and froze, waiting. What kind of reaction would the bank employee have? Would he curl the right corner of his mouth, wrinkle his nose, or rapidly blink? But there was no reaction at all. He just scooped up my passport and scanned it without even looking at it — as if it were a German or a French passport. The account was opened in 10 minutes using only my passport and the lease agreement.

Later, I found out that Americans can’t open accounts in Europe either. I personally tried several banks and brokers, and they all shut me down: “We don’t open accounts for U.S. citizens.” Meanwhile, banks in Mexico, Australia, Thailand, the UAE, Singapore, and dozens of other countries are happily doing business with Americans on a massive scale. Turns out Europe passed a data protection law that’s incompatible with U.S. tax law. Now, Americans are suing European banks to force them to open accounts.

European banks do not open accounts for Americans because the GDPR and the FATCA system are incompatible

One more observation: in America, it’s as if they have no idea what “nationality” is. Or, more precisely, the word itself, of course, exists in English. It just happens to mean something completely different from what it means in the rest of the world.

In all the former USSR countries, including Russia and Ukraine, the question “What’s your nationality?” is considered perfectly appropriate, even everyday small talk. The word “nationality” in this context — in both Russian and Ukrainian — means nothing more than ethnic background.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say there’s a person who was born and raised in Moscow, went to a Moscow school, is well integrated into Russian society, and speaks perfect Russian. His parents have also spent half their lives in Moscow and know Russian just as well. However, there’s a catch: his family moved to Moscow from Buryatia — a small republic in southern Russia — half a century ago. That’s why the young man’s face shows distinct Buryat features: narrow, slanted eyes, a smaller nose, slightly chubby cheeks, and so on.

Now, let’s suppose someone asks this person, “What’s your nationality?” If he answers, “I’m Russian,” most Russians simply won’t get it. Modern Muscovites will probably just leave it at that — liberal elite and all. But many people from the regions will respond, even a bit defiantly, “Russian? You? You’re a Kazakh!”

Aleksei Balabanov’s film Dead Man’s Bluff

Among all the former USSR countries, people especially love to talk about nationality in Azerbaijan. The author never tires of telling the story of what happened at the international airport in Baku. At passport control, I was stunned by the following exchange:

“Your nationality?”

“My what?”

“What’s your nationality?”

“Uhh... Russian...”

“Pure?”

“Pure. Russian. Yeah.”

“Welcome to Azerbaijan.”

“Welco... I mean, thank you!”

They ask these questions here politely and with a smile, almost innocently. The thing is, Azerbaijan has a long-standing conflict with neighboring Armenia. The two peoples hate each other. With her question about my “purity,” the passport officer was clarifying whether anyone in my family had come from Armenia. Apparently, my last name reminded her of an Armenian one. My Russian passport didn’t interest her at all, because in the former USSR, a passport determines your citizenship, while customs officials specifically check your ethnic origin.

In Eastern European countries, this kind of thing is rare, but they haven’t really gone that far from the Soviet tradition. In countries like Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Serbia, and dozens of others, there are words like národnosť and tautība, which mean ethnic origin. Latvians, Czechs, Poles, and Serbs can just as easily ask someone for their “nationality” and be surprised by a “wrong” answer.

Only in the most developed European countries, such as France and Germany, are the words nationalité and Nationalität used only in official documents and mean exclusively citizenship exclusively — that is, the country that issued the passport, and nothing more. It would never occur to a Frenchman or a German to ask someone about their nationality in a racial sense, let alone argue about it.

Alas, even in Western Europe, that’s more like politeness. Sure, no one here is going to question or argue about your nationality, but they’re not going to see an immigrant as a real Frenchman or German either. Someone who moved to France or Germany as an adult has almost no chance of becoming French or German in the full sense of the word.

But America isn’t like that. It’s not as if anyone who steps off a plane instantly becomes an American... But it’s pretty close.

The word “nationality” in English, just like in German or French, means citizenship and nothing more. If an American were to decide to ask someone about their ethnic background — let’s say under the influence of some heavy drugs — they’d use the word “ethnicity.” In practice, it’s only used on forms for collecting statistics, and in everyday speech, you’ll hear it from, at best, academics and country bumpkins.

So, to become an American — a real one, no asterisks, no footnotes — you just need to speak English fluently and at least generally share American values. That’s it. A passport? Who needs it? Half the country doesn’t even have one. What really matters is understanding temperature in Fahrenheit and knowing how many inches are in a foot. That’s why people say Americans don’t really exist, and it’s not a nationality. And they’re absolutely right! It’s just that Russians and French people don’t exist either. Ethnic groups and races don’t exist in a purely biological sense, and the word “nation” is basically a 19th-century invention.

So yes: America is not a nation, which is actually a very good thing. It’s more like a hobby club where last names, accents, skin colors, and family recipes all mix and fuse into a new identity. That’s why America is called a melting pot. Once you land in that pot, there’s no getting out. Only in this country can you be born into an Ethiopian family, grow up in an Italian neighborhood, go to a Jewish school, and still be American!

The Principal Sortes of Americans.

Many countries have tried to copy the American experiment. The USSR forged the “Soviet man,” or Homo Sovieticus, who could be Russian, Georgian, Tatar — take your pick. Yugoslavia tried to melt Serbs, Croats, and Albanians into one big “Yugoslav.” China is still, in vain, spinning its single “Chinese nation” out of endless Tibetans, Uyghurs, Zhuangs, and another 53 peoples who don’t even speak the same language.

All these attempts are doomed to fail. It’s one thing when a nation is created by the settlers and migrants themselves. It’s a completely different story when you try to forcibly melt down peoples whose identities have been forming for centuries.

As for the American melting pot, these days, people increasingly say it’s stopped working. The thing is, in the past, immigrants would fully blend in, becoming Americans and saying goodbye to their old identity. Today, that’s no longer the done thing. If before a Russian, a Mexican, or an Ethiopian became an American instead of their old self, now they become an American in addition to it. Sometimes it’s written just like that: Russian American, African American, DPRK American, and so on.

Besides, if long ago people of all backgrounds used to spread out evenly across America and sort of dissolve into it, today more and more ethnic neighborhoods are popping up in major U.S. cities. No, it’s not like there were none before. The famous Chinatowns arose because Chinese people weren’t allowed to buy housing anywhere else. Now it’s become a lifestyle choice.

A typical Saturday in Brooklyn

For these two reasons, the American melting pot is now often called a “salad bowl.” But the pot hasn’t broken. It’s just started working differently. If immigrants used to say, “we’re all the same,” today they say, “we’re all different, but together we’re Americans.”

It’s the spirit of the times, not a malfunction. A boiler built from 18th-century blueprints can’t run for two centuries straight without replacing any parts. And still, even in ethnic neighborhoods, the way of life is more American than Jewish or Chinese, and in schools, universities, and at work, all nationalities get mixed together without distinction.

A generation will pass, and the children of the new immigrants will scatter from the ethnic neighborhoods across Greater America just like their parents once left for America itself. That’s how it was, that’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be.

Sluggish depression

Imagine that after the 1929 crash, the U.S. government didn’t panic, but instead suddenly printed a colossal amount of money. What would the Great Depression have looked like then — and would it have happened at all? History doesn’t do “what if,” and under normal circumstances, we’d never know the answer to that question. But America is a country of abnormal circumstances.

The story of the crisis we’re living through today began in the early 2000s. And it began the same way as the story of dozens of other crises, including the Great Depression.

After the stock market crash that went down in history as the “dot-com crash,” and the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to give a good kick to a shaken and frightened economy. Two years earlier, the government had also repealed the 1933 banking law that prohibited banks from investing customers’ money in anything other than safe government securities. That law was considered outdated and harmful to the economy, and now banks could put money wherever they wanted, including into stocks and businesses.

The result didn’t take long. America was slowly coming back to its senses: stocks went back to rising, and banks started handing out loans like candy. But real estate was feeling the best of all.

All through the 2000s, the housing market was growing like crazy. Interest rates were low, and pretty much any American could get a mortgage. Special “affordable” programs were created for the unemployed and low-income, so a person could get a house with no down payment and not even start paying interest for a few years. They didn’t always ask for proof of income, either. And where exactly is an unemployed person supposed to get that, right? So banks often approved mortgages on the honor system: the borrower just wrote down their income on the application, and almost nobody bothered to check it.

The most popular of all was the so‑called “subprime mortgage.” Oh, that thing sold like hotcakes! No wonder, since its name was cooked up by marketers as a polite way to describe a mortgage for people with credit scores so low that ten years earlier they wouldn’t even have been let through the bank’s front door. Crap mortgages, to put it simply.

Who exactly took out these crap mortgages? A whole cross-section of the society: red-plaid hillbillies from sawmills in Arkansas, rosy-cheeked pig farmers from Kentucky, whiskey-soaked cowboys from Texas ranches, truckers’ abandoned wives from Nebraska, moss-covered raccoon hunters from Idaho, and descendants of Russian reindeer herders from Alaska. Hmm, someone’s missing... nah, nevermind.

Of course, upper management understood perfectly well that handing out mortgages like that could bankrupt the bank. So the young financiers came up with a scheme. The bank would issue a thousand junk mortgages, mix in a couple of good ones for respectability, slap a label on it saying “Best Homes in America Fund,” and sell it on the exchange to investors. In turn, the rating agencies would give these junk funds the highest AAA credit rating, because housing prices were going crazy and could supposedly cover any losses.

Everything was just peachy. Everybody won. The rednecks and the blacks got housing. The banks got money from selling the funds. The investors who bought the funds got interest from the mortgage payments. The credit agencies... well, they couldn’t have cared less about any of it.

So where exactly was the flaw in this brilliant scheme? The flaw was that absolutely every single character in this tragicomedy — from the country bumpkin to the financial analyst at Bank of America — was utterly convinced that housing prices always go up. As in, no one in the whole vast United States could even begin to imagine that houses might actually go down in price with no less speed than that of a dive bomber!

Then something utterly unprecedented and unheard-of happened (sarcasm). The Federal Reserve decided that the economy had already recovered and that it was time to raise rates. They hiked it, and pretty fast: if in 2004 it was 1%, by 2006 it was over 5%.

Fed funds rate before the 2008 crisis

That very same year, housing prices, which “always go up and never go down,” suddenly stopped rising. The price chart wheezed and lumbered its way to the peak of its growth, sat there for a couple of months, and then went tumbling down like a roller coaster.

Suddenly, it turned out that nobody in all of America had counted on this, and the whole setup depended on the idea that even if some white hick from Idaho or a black guy from South Central couldn’t pay the mortgage, you could always sell the house — and for an even higher price at that.

Everything was going fine until 2007, when suddenly, at the beginning of spring, one of the banks that issued mortgages went bankrupt. Banks in America go under from time to time, so the news didn’t attract much attention. However, soon after the first, a second bank went bankrupt, then a third, and a fourth. In just one year, more than a hundred banks and various mortgage companies went bust, but even that didn’t make much of an impression on investors. After all, housing prices can only go up, right? Most people were just waiting for the market to pull itself together and start climbing again. Especially since the rating on those junk funds was still the highest possible — AAA.

The climax of this whole epic came a year later, in the fall of 2008, when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt — a financial dinosaur founded in 1850 and the fourth-largest bank in the United States. And that’s when the AAA rating finally turned into AAAAAAAA!

The stock market didn’t just fall — it crashed, straight into a vat of garbage. In a few days, shares lost a third of their value. Interbank lending went into a tailspin: banks refused to lend to each other, even overnight, because by morning, the borrowing bank might not wake up. Scam funds went straight to hell, and investors started panic-selling anything that could still be sold, driving the market into an even steeper dive. In the end, the market collapsed to 53% below its 2007 peak.

America hasn’t seen a crisis like this since the Great Depression... Except there was no real crisis, more like what people like to call a crisis. Stock prices fell — that’s true. Thousands of people lost their jobs — that happened too. The question is this: were stock prices fair before they fell, or did they actually return to a fair level? And were people being fired from jobs created by real demand, or by artificial demand?

With all due respect to the Americans who lost their jobs, I find it hard to call a 20% drop in housing prices a “crisis” when food prices barely changed. It seems like in a real crisis, prices are supposed to go up. What actually happened in 2008 was more like the deflation of a bubble that had been pumped up for six years straight by handing out cheap loans to anyone who wanted one. The economy, therefore, didn’t so much collapse as it started to recover and move back toward market equilibrium.

The average consumer actually came out ahead from this so-called “crisis” because housing prices fell. Aside from those who lost their jobs, it wasn’t the average consumer who really suffered, but rather stockholders, real estate investors, and the banks that handed out unsecured loans. They’re the ones who lost insane amounts of money — and they’re the ones the U.S. government decided to rescue.

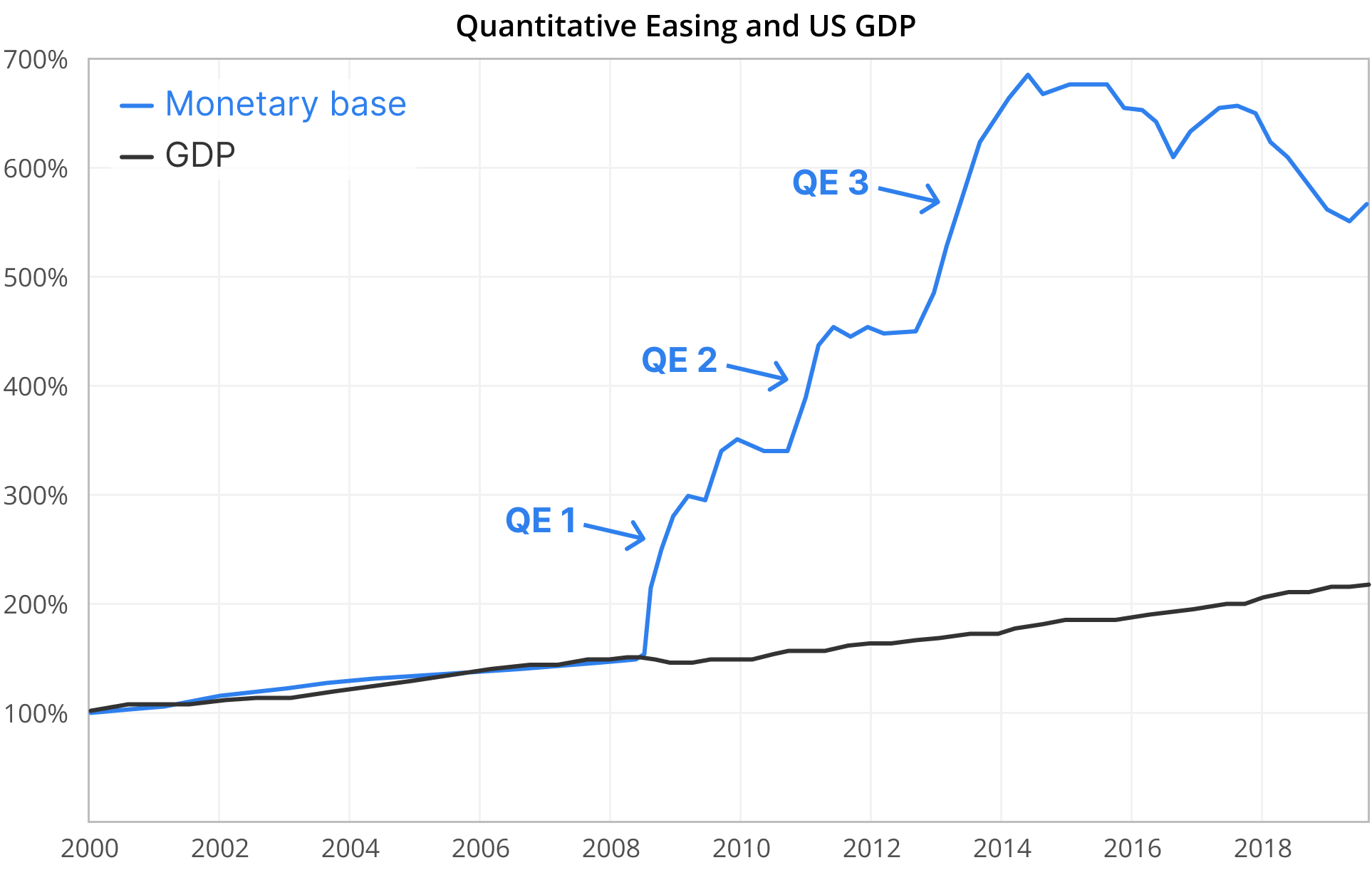

That’s when it appeared on the scene — quantitative easing. Along with “subprime mortgage,” it’s another term dreamed up by bank marketing people. You can’t very well say “printing press” in public. So they say: quantitative easing. Although there’s a grain of truth in the name — money isn’t literally printed, it’s credited to a bank’s account against its assets as collateral. But of course, details like that don’t change anything.

The money was printed in three rounds. The first round produced $1.7 trillion — an unthinkable amount, larger than Russia’s GDP. The second was a modest $600 billion, and the third was an unthinkable $1.6 trillion. In just 6 years, the Federal Reserve printed almost $4 trillion, increasing the monetary base by nearly 8 times. For comparison: all the money in circulation (M2) before the crisis was $7.5 trillion.

U.S. Money Supply Surge After 2008

That was a very historical experiment America carried out. After the 1929 crash, the Federal Reserve was completely at a loss. The money supply didn’t grow; it shrank by a third. Only with Roosevelt’s arrival and the abandonment of the gold standard in 1933 did they start “pumping” money into the economy — but very slowly and very hesitantly.

That’s exactly why the Great Depression became “great.” In reality, it was just an ordinary crisis, the same as in 2008, stretched out over a decade by clueless policies and populism. If in 1929 they had flooded the economy with a trillion dollars and cut interest rates, the term “Great Depression” would never have been born. The reverse is also true: today America is living through the same kind of “Great Depression,” only masterfully covered up by printing trillions of dollars. Same thing!

There are three things one can watch forever: a fire burning, water flowing, and America collapsing.

Many economists, such as Peter Schiff and Ron Paul, lost their heads after the 2008 crisis. They were shouting themselves hoarse that injecting money would only postpone the collapse, which was sure to catch up with America in just a couple of years. When the crash didn’t happen after a couple of years, the timeline was pushed back to five years. When the crash still didn’t come after five and even ten years, the economists had to make excuses saying that they were wrong about the timing but not about the essence, and that sooner or later the collapse would inevitably arrive.

Funny thing is, while they were busy making excuses, the economy had already long since suffered a full‑blown crash. Nobody noticed it, though, because the crash didn’t look like a Hollywood‑style system collapse — with starving queues and people jumping out of skyscraper windows — but like something completely different.

It turned out that in developed countries, food demand is so well met that increases in the money supply hardly lead to goods inflation. No matter how much you might want to, you can’t eat more burgers or wear two pairs of cowboy boots at once, even if money is handed out directly in the form of checks. So all this mass of money flowed not onto store shelves but into the stock market and... into real estate, whose prices rose by 50% once again. Hot on the heels of apartment prices, the prices of gold, education, healthcare, and also bitcoin shot up — basically, everything that you don’t need to eat can’t be printed.

Finally, what really crushed the American economy was the pandemic — or, more precisely, the inadequate response to it. During the lockdown, the Federal Reserve went all out and printed, in addition to the previous 4 trillion, almost 10 trillion dollars more.

This fantastic figure consists of two equal parts. The first is a new round of quantitative easing of $4.8 trillion for the banks. The second part is $5 trillion in cash checks and subsidies to people in quarantine. And if easing is “money printing” in a figurative sense, then the checks are real printing, without quotation marks.

A $1,800 stimulus check given to Americans

As a result, housing prices shot so far into the stratosphere that the previous bubble, compared to the new one, started to look not like a bubble at all, but a small ripple on the water. In the ten years since 2012, apartment prices have increased 2.5 times!

Today in America, buying a home in a major city seems impossible. The author rents a small two-room apartment for $2,500 a month. Its area is just under 50 m², and it’s about an hour by subway to Manhattan. In Manhattan itself, good apartments are rarely rented for less than $3,500, and they cost at least a million. A house in Texas costs four times less.

The rise in apartment prices wouldn’t be a problem if wages were growing at the same pace. But by the late 1980s, housing began to pull away from incomes. Whereas before the average home cost about three times the average annual salary, today it’s about six times that amount. Education costs have shot into the same stratosphere: Americans take on loans to study at a prestigious university and then spend many years paying them off out of each paycheck.

As for the national debt, these scare stories come from a misunderstanding of its nature. Only 20% of U.S. debt is owed to other countries. All the rest is domestic debt, which is easy to service and largely consists of technical obligations such as pensions.

America’s tomorrow is not a default on debt, but a sluggish depression where buying a home will be impossible for the next couple of decades.

Rich and Poor

Despite all its problems, America is an insanely rich country.

Helicopter taxis routinely shuttle back and forth over New York, taking passengers from the airport to downtown and back. Prices start at $200 per seat. That’s practically nothing even for a non-business traveler, since a regular car taxi can cost $150 for the same route during rush hour.

Central Park, which really ought to have been renamed Central Forest by now, is growing a tall fence of skyscrapers all around its perimeter. The towers peer alien-like through its thickets, in such unusual shapes and colors that even Dubai would be jealous.

A penthouse in such a high-rise can cost a hundred million dollars — a price that sounds more like the GDP of a small African country than the cost of an apartment.

The streets of New York are packed with expensive boutiques. It’s a real paradise for shopaholics, who flock to the shiny trinkets like flies to jam. Major brands set their lures out on the city streets and compete in the extravagance of their ideas. Today, Louis Vuitton is in the lead, having come up with the idea of building a skyscraper in the shape of a suitcase.

At the other end of the city is the very wealthy Dyker Heights neighborhood. Every Christmas, it’s decorated so lavishly that the electricity alone costs $5,000–8,000 a month for a single house.

In the state of California, there’s the city of San Diego, and its Mission Hills neighborhood can bring tears to your eyes. The scenery here looks as if someone cranked up every slider in Photoshop.

This is where the old money lives. Most of the houses in this neighborhood were bought back in the early 20th century. They belong to families of doctors, lawyers, and bankers and are passed down through generations. You can’t buy a house here for less than $2 million.

In another famous city — Miami — red Lamborghinis casually park by sunny cafés, while three-wheeled sports cars are rented out to tourists by the day as glittering junk.

But for all its splendor, America can be frighteningly poor. In the wealthy city of New York, on Broadway, right across from a cluster of expensive boutiques, African refugees spread out counterfeit copies of bags, watches, and Apple headphones on the sidewalk to sell.

On another famous street — Fifth Avenue — some hundred steps from the suitcase-building, the eye picks out from the crowd of tourists and shopaholics the figure of a half-naked beggar woman wrapped in a bedsheet.

Across the country, zones of open drug addiction are multiplying. In Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Denver, Baltimore, Boston, and dozens of other cities, entire streets and neighborhoods are occupied by drug users injecting fentanyl into their veins in full view of passersby. The authorities are unable either to arrest or to treat the millions of fallen people.

And many other places are just plain poor. In those lesser‑known states, you can find roads smashed to bits, filth, and never‑drying puddles that are no better than their older sisters back in Russia.

Social media alternately shows two countries: the America of the rich and the America of the poor. Everyone chooses for themselves which to believe, but of course, both sides are right. America is not Switzerland. It’s too big to be the same everywhere.

This is called social inequality. It is measured by the Gini index — a number from 0 to 100. The higher it is, the more wealth belongs to a narrow circle of people, and the lower it is, the smaller the gap between rich and poor. Of course, there are no extremes, and all countries lie somewhere in the middle of this scale. In the United States, this index is 40 points, which is much higher than Europe's 30 points.

We all intuitively know that in Europe there is no such chasm between the rich and the poor as the one gaping in the United States today. But low inequality does not mean prosperity. For example, Pakistan’s Gini index is also 30 points, even though it is one of the poorest countries in the world. Naturally, if everyone in a country is equally poor, inequality will be very low!

Obviously, even a poor American lives better than a Pakistani with an average income. For example, back in 2010, 80% of poor households in the U.S. had air conditioning — a luxury unavailable to 5 billion people worldwide. And in terms of housing space, the gap is large even compared to Europe. A poor American has 41 m² per person, while an average German has 46 m², and an average Briton only 38 m².

It’s interesting to observe how American socialists manage to turn even such facts inside out. For example, one article states: “One in five poor families cannot afford air conditioning.” But one in five poor families without air conditioning means that 80% of poor families have air conditioning, just as mentioned above. Thus, even the record-level availability of what is, generally speaking, elite equipment is presented as a failure of capitalism.

Regarding salaries, comparing countries by income is completely pointless because expenses differ so much. It’s much smarter to compare what’s left at the end of the month. After all expenses, including insurance, rent, and food, the average American family puts $2,250 into savings. There’s no equivalent data for Europe, but according to the author’s estimates, the average German family saves about €1,000, even taking free healthcare into account.

And still, these numbers mean very little. How do you get an average balance of $2,200 at the end of the month? Very simple. You need 80% of Americans to be saving $3,000, while the rest go $1,000 into debt. Judging by surveys, that’s more or less what’s happening: half of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. It’s just not clear whether they’re spendthrifts or genuinely poor.

Who is to blame for such stratification? Without irony: capitalism — the brutal system of selection, similar to the conditions of the wild, only for humans. And American capitalism, although heavily diluted by Roosevelt’s legacy, still remains the purest one on this unfortunate planet.

Socialists make the correct diagnosis. Where they go wrong is in choosing the treatment. Modern leftists understand that, for example, there is no such thing as free healthcare. That’s why they propose to redistribute income and pay for it through huge taxes on the rich. Indeed, even if Bill Gates gave away 99% of his wealth, he would still remain a billionaire. It seems that having that much money while millions of people cannot afford insurance and housing is moral insanity.

Let’s leave aside the fact that Gates has given $60 billion of his own money to charity and plans to give it all away. Billionaires won’t be impoverished by high taxes. It’s much worse than that. The point is that the rich don’t earn salaries; they hold their wealth in the form of stocks. But stocks are not income, and you can’t tax them as such. To carry out this plan, you’d need a mechanism for expropriating property. And creating such a mechanism is a direct road to a totalitarian state of the kind seen in Stalin’s USSR or Hitler’s Germany.

Russia went through this lesson in the early years of the Soviet Union.

Starting with a struggle against wealthy landowners, Lenin’s reforms quickly went into a tailspin, turning into terror. After dealing with the rich, the Bolsheviks declared the kulaks — the rural middle class — to be enemies of the people. Then came prodrazverstka (literally, food apportionment) — the forcible seizure of grain, now from all peasants, for the benefit of the army. The result was mass famine and millions of deaths. The experiment led to such upheavals that Lenin himself rolled back socialism. As early as 1921, he announced the start of the NEP — the New Economic Policy based on the market — carefully describing his capitulation as a “temporary retreat.”

The Soviet NEP felt much like America’s Roaring Twenties. Main dining hall of the Hotel Evropeiskaya, 1924

Stalin launched a new offensive by beginning the dekulakization campaign. Once again, he declared the well-off peasants enemies. Once again, people had their grain taken away, and those who resisted were sent to labor camps. And once again, there was mass famine, which in 1932–1933 struck Ukraine, the Volga region, and Kazakhstan — the most fertile lands. After this experiment, which cost between 5 and 7 million lives, Stalin allowed peasants to have private farms.

Since then, no such experiments have been carried out in the USSR, and socialism has become a beautiful façade. On the upper floors of the Soviet system, the grand figures of the state planning committee thundered, factories stamped out products, collective farms broke milk-yield records, and red-and-yellow posters blazoned about the victories of socialism. This picture was what they sent abroad — to America and Europe.

But the lower floors that held up the façade were seen only by those on the inside. While those at the top talked about “provisioning,” the lower levels were ruled by a wild market. At the makeshift markets, elderly babushkas crowded together, selling potatoes from their gardens in metal buckets. You couldn’t buy a car, a television, or even a wardrobe in a store. They were hidden away in warehouses to be later traded through connections for a crate of tangerines, imported cigarettes, or expensive cognac.

While the top floors were drafting the state plan, workers on the lower floors were sneaking factory parts out and selling them on the black market. The directors had trucks running between plants under the cover of night. They weren’t hauling contraband, but missing components. One factory never received its ball bearings, another was short on metal, and a third had no wiring. So the directors of these “advanced socialist enterprises” would call each other and sort it out: “I’ll give you my surplus, you give me yours — otherwise we’ll both shut down.”

Capitalism solves these problems on the fly through market prices, but under socialism, prices are set by the state based on calculations far from reality. Space flights and free healthcare were merely a façade of socialism, behind which smoldered a grassroots capitalism, preventing the Soviet system from collapsing. When it finally burned out completely, and oil prices collapsed, the country even had food shortages. Failing to reach its 70th anniversary, socialism collapsed from exhaustion and never stood up.

The author witnessed Russia’s transition to capitalism. In the regions, it dragged on for about ten years, so the dying out of socialism took place before my very eyes. My funniest memory is of the shops with numbers instead of names, each selling only one type of goods, and all keeping different opening hours.

Let’s say that if you wanted to buy bread, sausage, and an exercise book in one trip, you had to go to three different stores. Sausage was sold at Store No. 45, books at Store No. 66, and bread was sold at the store next to my house, whose number nobody knew, so it was just called “ours.” The tricky part was that Store No. 45 went on lunch break from one to two, Store No. 66 from two to three, and at ours, they only had fresh bread in the morning. It seems the three-body problem is easier to solve than the problem of three Soviet stores.

When this rotten system was killed off by capitalism with its supermarkets, it was a breath of fresh air. Today in Russia, there are no shortages, despite the war and sanctions. And although older people feel nostalgic for Soviet times, it’s harder to find a socialist in Russia than in Manhattan, where people know about socialism about as much as a virgin knows about sex.

Today, there’s little left of socialism in Russia: the labor code, child benefits, half-dead free education, and healthcare.

But now it was Europe and Canada that turned social. You get free healthcare, education, unemployment benefits, and generous pensions. The homeless are entitled to housing and welfare, and you can’t fire anyone without a hefty payout, even if they’re blatantly slacking off.

Just like in an economics textbook, a high minimum wage led to a rise in unemployment. In December 2024, youth unemployment was 25% in Spain, 24% in Sweden, 21% in Greece, 20% in France and Portugal, and 19% in Italy and Finland. Nobody wants to hire young people for the kind of money the law says they have to be paid.

The pension system has also gone bankrupt. People are living longer, while the birth rate is falling. So fewer young people are paying taxes, and more and more elderly people are receiving pensions. But “the old investors live off the new ones” is the classic formula of a financial pyramid. Europe started bringing in migrants, counting on an expanded tax base, but many of them just went on welfare, which only made things worse.

The result of the social experiment is once again depressing. If in 2008 Europe’s economy was on par with America’s, by 2023 it’s lagging behind by almost half.

The same thing happened on another continent. Before the socialist Justin Trudeau came to power, the Canadian and American economies moved like synchronized swimmers, but eight years later, Canada is lagging 17% behind the U.S.

But why? After all, there really are plenty of intellectuals and scholars among socialists. Could they really have lost out to the caveman understanding of the market that flourishes among American hillbillies? I’m not in a position to answer that question. I’ll hand the floor over to Friedrich Hayek — Nobel Prize laureate in economics — who answered it half a century ago.

And the people who imagine, oh, it should be possible to design all this, to arrange this, accept the government to do this in a manner that the distribution is just. Now that is literally impossible!

However, ideas of equality are sometimes so attractive that people are willing to sacrifice prosperity and economic growth. Older Russians sometimes remember the USSR like this: “Sure, we lived modestly — but at least we were all equal!”

Socialists believe that their world — though less successful — is more just. But it seems that the idea of equality is based not on lofty humanism at all, but on primitive animal instincts.