Riga, Latvia

Public transportation in the Baltic states is represented by a wide range of vehicles: buses, trolleybuses, trams, trains, and minibusses. It is convenient to travel around cities at any place and time.

The ticketing system in Riga suffers from an incredibly foolish issue: if you buy a two-ride ticket, only one person can use it. The ticket won’t be accepted for a second time on the same bus. Moreover, the electronic validator doesn’t provide any understanding of this problem as it displays information only in Latvian.

As a result, if several people are traveling together, it is not possible to buy a single ticket for ten rides and have everyone pass one by one. Each person needs to purchase their own ticket and validate each ticket separately.

The ticket inspectors are certainly lenient towards tourists. They offer to pay the fine on the spot with a discount. At first, I thought they were pocketing the money. It turned out that the discount is official.

The ticket price at the machine is 1 euro, while with the driver it’s 2 euros. The fine ranges from 20 to 50 euros, depending on the number of violations within a year.

There are minibuses in Riga. It’s completely unclear why they exist here since public transportation already functions well. But there are minibuses. Not the beaten-up yellow Ukrainian “Bogdans” that roam around Moscow, but very decent Mercedes microbuses.

The buses are also Mercedes, but not the newest ones.

Sometimes you come across an old Hungarian Ikarus bus.

Old trams of the Czech brand “Tatra.”

The interior of the Tatra tram is not much different from the red and yellow Moscow trams. Same manufacturer, same brand. The only difference is 20 years. Such trams are still in operation in half of Europe and throughout Russia. Few people know that they were produced in Czech Republic: we have become so accustomed to them that they seem familiar.

Gradually, they are being replaced with luxurious modern trams from Škoda.

However, Škoda has been supplying trolleybuses for a very long time.

The interior of the new tram is spacious, bright, and comfortable. The only questionable aspect is the morally outdated upholstery of the seats.

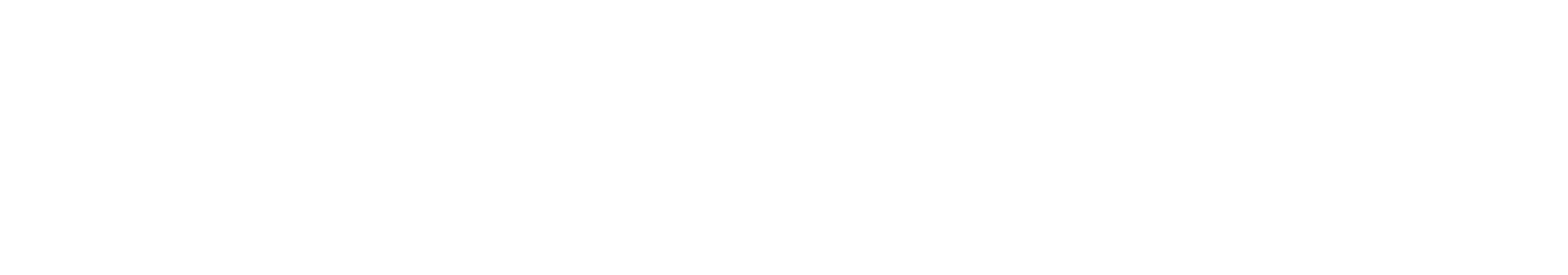

The electronic display in the tram shows a list of stops and the route on Google Maps.

The rails are in perfect condition.

Freight tram.

Bus and tram stop. Almost always equipped with a ticket vending machine and a convenience kiosk.

Another bus stop closer to residential areas. The stops are modest, but none of them are plastered with announcements — the authorities in Riga have managed to deal with advertising clutter.

In most residential areas, however, the bus stops have the same name. It’s a downside, but I’m not sure if the residents are greatly affected by it. Riga is not a metropolis; there are no traffic jams or a frantic pace of life here. People know exactly when their bus will arrive, come at the right time, and board it. It’s unlikely that the absence of a roof at the bus stop causes discomfort to anyone.

The ticket vending machine operates in multiple languages.

The schedule and routes are designed quite neatly.

Latvian taxi.

Bike rental. Cycling infrastructure in Riga is weakly represented. If bike lanes are encountered, they have not left a lasting impression in people’s memories.

Parking in the center of Riga is paid, and the cost depends on the proximity to the city center: on average, it ranges from 1 to 5 euros per hour. The parking sign is supplemented with an icon of an old mechanical parking meter.

The icon, however, resembles more of a scale, as modern parking meters look quite different.

Riga’s suburban electric trains deserve a special mention. Suburban routes are served by the electric trains from the Riga Wagon Building Factory. These trains, with the well-known RVR emblem, are used throughout Russia.

The history of the Riga factory is fascinatingly sad. Initially founded in 1895 as “Phoenix” by German entrepreneur Oscar Freiwirth, who was a shareholder of another major enterprise, the Russian-Baltic Wagon Factory.

At that time, Latvia was still part of the Russian Empire. During World War I, the factory was relocated to Rybinsk. Later, the factory was reestablished in Riga as a completely new enterprise in 1923 when Latvia had already become an independent republic.

The factory operated successfully, supplying thousands of wagons as per the orders of the USSR until the mid-1930s, when it became unprofitable and was sold to the Latvian company Vairogs. Vairogs then restructured the factory for the production of automobiles and trucks in collaboration with Ford.

During World War II, the factory was severely damaged and later restored by the Soviet Union. It was nationalized and renamed “Riga Carriage Building Plant,” which continues to produce primarily electric trains and trams to this day. The Riga Carriage Building Plant (RVZ) developed the first diesel trains and the first high-speed train, ER-200, in the Soviet Union. In addition to wagons, the plant briefly manufactured refrigerators, children’s furniture, and sleds. During its peak years, RVZ employed 6,000 people.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the factory became an independent company, but production started to stagnate due to a complete lack of demand in Russia. Eventually, RVZ went bankrupt in 1998 and was sold to the same company, Vairogs, and the Latvian holding company Felix.

In the new century, the factory accumulated insurmountable debts of 10 million euros, using all its property as collateral. By 2012, only 95 people were employed at RVZ, compared to its former staff of six thousand! The unprofitable plant was attempted to be sold for a long time, but it was challenging to find a buyer for the old ruins. Eventually, it was sold to a certain company called East-West Group, a strange entity established within a few days specifically for purchasing the factory.

The future of the former railroad titan is currently unclear. However, in the present, well-known electric trains are operating in Latvia, recognized throughout Russia.

The models were slightly modernized: exits were equipped with steps, and compartments for bicycles were created inside the carriages.

Some salons were modernized: they installed new seats, shelves, and handrails, and cleaned them.

In another part, they limited themselves to replacing the linoleum, doors, and upholstery.

The platforms outside of Riga are in a terrible state: dilapidated and abandoned, without roofs or proper pedestrian crossings across the tracks.

The stations are so low that passengers have to jump off the trains. What was the point of installing steps then?...

Bulduri Station.

Imanta Station.

And here is a truly magnificent old station in the heart of Riga. That’s how they all used to look like. It’s wonderful that at least a few of these historic buildings have been preserved.

Tallinn, Estonia

Tallinn’s buses are produced by three renowned companies: Scania, Volvo, and MAN.

The trams in Tallinn are still the same Czech Tatra models from the mid-1970s.

The interior of this tram is no different from that of the Riga tram.

Tram stops in the city center are designed as large, safe “islands.” The rails along all routes are in good condition.

In a couple of places, the tram even passes through a modest patch of grass.

On one of the lines, modern trams produced by the Italian company CAF have been introduced.

Excellent, spacious cabin with accordion-style folding. The seats have let us down again. Why can’t they upholster them with faux leather? Why are the seats wrapped in such shabby fabric in such an expensive tram?

Even the budget for large screens displaying the trip route and satellite navigation maps was sufficient. But there is no budget for proper upholstery?

The validator design is beautiful. Unlike in Riga, in Tallinn, multiple people can travel on a single card. However, the process is incredibly complicated. Do you see the arrows on the validator? To deduct two tickets from the card, you need to tap it on the validator, select the desired number of tickets with the arrows, and press OK.

One might wonder: why can’t you simply tap the card twice? It’s astonishing how a problem can be created out of nowhere.

One ticket costs 1 euro at the vending machine and 1.6 euros from the driver. The fine in this case is twice as much as in Riga: a whole 40 euros. A warning about this is presented thoughtfully in two languages: Estonian and Russian.

One of the tram lines has been closed for repairs. Signs along the track have been crossed out with bright orange crosses. On those sections of the track where certain trams have stopped running, only their numbers are crossed out, not the entire sign.

The tram stop sign before the pedestrian crossing. Interestingly, the Estonian language’s characteristic of doubling letters even manifests in the simplest words.

Bus stops in the city center. Benches, like everywhere in Europe, are made narrow so that homeless people don’t sleep on them. It helps to some extent.

Hanging at the bus stops is a huge city map with a prominently marked center. The map shows the routes of all transportation. However, the lines are not differentiated by color. Bus routes are blue (they were actually green but faded). Trolleybus routes are also blue, just slightly brighter. Tram routes are yellow. Good luck to colorblind individuals.

But the map developer thought that wasn’t enough. They decided to label the route numbers along all the lines with the same color. To understand where bus number 9 is going, you have to trace your finger along the entire line as if navigating a maze.

Such absurdity is hard to find. Tallinn positions itself as an advanced design city but cannot find a competent designer for the transportation scheme.

Fortunately, next to the pole, there is a timetable for a specific bus that passes through this stop. It provides some means of orientation.

Indeed, it happened by chance that the timetable is hanging right next to the garbage bins. Well, never mind, it will do for now.

The railway transport situation in Estonia is somewhat better than in Latvia. The old trains are produced by the state-owned company “Estonian Railways,” which was formed as a result of the division of the Soviet enterprise Baltic Railways.

The old models of Estonian trains operate throughout the country, and one of them even used to run to Moscow until recently.

In 1998, the company Elron separated from the enterprise and started developing modern suburban electric trains. These trains look very cool and modern. Unlike the Riga plant, the Estonian company brings in good profits.

What Tallinn lacks is bicycles and parking. There simply aren’t any in the city. Guidebooks mention bike rentals, but I’ve searched every corner of the city and haven’t come across a single one, nor have I found a single bike path. They’ve hidden them well.

As for parking, there are parking meters, but it feels like everyone parks however and wherever they want.

At the exit from the historic part of the city, taxis are lined up in neat rows. Well, if they’re standing there, it means they’re not in high demand.

And in general, not taxis but “takso” (the local term for taxi).

Vilnius, Lithuania

In Vilnius, there are bike paths.

Most often, they are simply painted on the sidewalk with paint.

Bike rental. Almost all bicycles are taken apart — they are in use.

Among all three Baltic cities, cycling is most developed in Vilnius.

Vilnius buses are older models of Mercedes, Volvo, and a newer “MAN” brand.

On some routes, there is a small cut-off section of the bus operating.

Its interior is half the size of a regular bus, and it appears messy and cheap.

Trolleybuses are from the Polish company Solaris and the Swedish company Skoda, models from the 1980s.

Trolleybus interior.

On several routes in the city, there are modern models of trolleybuses in operation.

The Lithuanian minibus, known as a “marshrutka,” is usually a Mercedes or Fiat microbus. It is not much different from the Ford Transit seen in Moscow. They are similarly worn-out and covered in advertisements.

Bus stops in the city center.

Dedicated lane for buses, taxis, and—unexpectedly—electric vehicles.

Absolutely charming transportation schedule. It is designed as a rotating hand cylinder that is placed on a pole.

Map with route movements. Even worse than in Tallinn. It is completely impossible to make sense of this mess.

Paper tickets are still used in Vilnius transport, which are punched by a mechanical validator. There are also travel cards available. That’s why two types of validators are installed in many buses.

The discount system is the same as everywhere: the fare when purchasing a ticket from the driver is 1 euro, and with a card it’s about 70 cents.

Mirrors are often installed on sharp turns, exits, and parking lots.

Parking meter.

Paid parking in the city center. The sign is almost the same as in Russia. The days of the week when parking is allowed are indicated by Roman numerals.

Overall, the parking situation in Vilnius is the worst among all three Baltic capitals. Everything is crowded here, from the historical center to residential areas.

On one of the most central streets, the problem was solved with an underground parking lot.

Vilnius taxis are predominantly regular cars with a yellow roof sign.

The story about Vilnius transport turns out to be the shortest. The city has neither trams nor interesting electric trains. The bus and trolleybus network is the least developed among the entire Baltic trio.

If transportation in Riga is simply wonderful and there are some inconveniences with navigation in Tallinn, then in Vilnius, one simply doesn’t want to take public transport. The routes are organized in such a way that it’s easier to walk around the city. The movement scheme is so confusing and intricate that the author ended up going in the wrong direction twice within half an hour, no matter how carefully they read the map.