Bratislava

In school, I had a question that interested me. If everything is so good and clean in Europe, and everything is so bad and dirty in Russia, then where does European cleanliness end and Russian devastation begin when moving from west to east? How does this happen? Do cities, villages, and roads gradually deteriorate and become worse, or does it happen abruptly, with all the good ending exactly at the border between the two countries?

Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, is only a hundred kilometers away from Vienna, Austria. That’s less than the distance from the center of Moscow to the border of the Moscow region. They are the closest capitals to each other in the world. And after traveling such a short distance between them, I found the answer to the question that had been tormenting me for so long. At the border between these countries, European cleanliness abruptly ends, as if with an axe, and Slavic devastation begins.

There is a train between Vienna and Bratislava every hour. A round trip ticket costs 15 euros.

Bratislava is immediately greeted by a shabby, rusty station with dreadful benches designed for hippopotamuses.

Jumping ahead, I will say that Bratislava is divided by the Danube into two completely different parts. The first part is the historical center of the city with old buildings. The second part is a breeding ground for panel houses, one large residential area. In reality, this is not so important because there is devastation in both parts of the city. However, since the train arrives in the residential areas, the story begins with them.

As soon as you step off the platform, something imperceptible in this unremarkable pedestrian crossing already reminds you of Russia. Perhaps it’s the details. Traffic light poles stuck in the middle of the crossing. A shabby fence in the median strip (at least it’s there), peeling trees in the background, a tasteless business center clad in cheap panels.

Beyond the crossing, the courtyards begin. And there are no doubts left about where we are.

Enclosure for trash bins. It is ugly, but at least it has a roof.

Variety of garbage bins.

Well-trodden roads. Such roads can be found in Vienna as well, but certainly not in such quantity and magnitude.

Shops on the ground floor of residential buildings. Worn-out, cracked asphalt. A green fence surrounding a small green area.

We continue moving deeper into the city.

Not only shops but also garage complexes are being built in the houses.

Mailbox.

Some building resembling a kindergarten or school.

Backyard.

Solitary high-rise building.

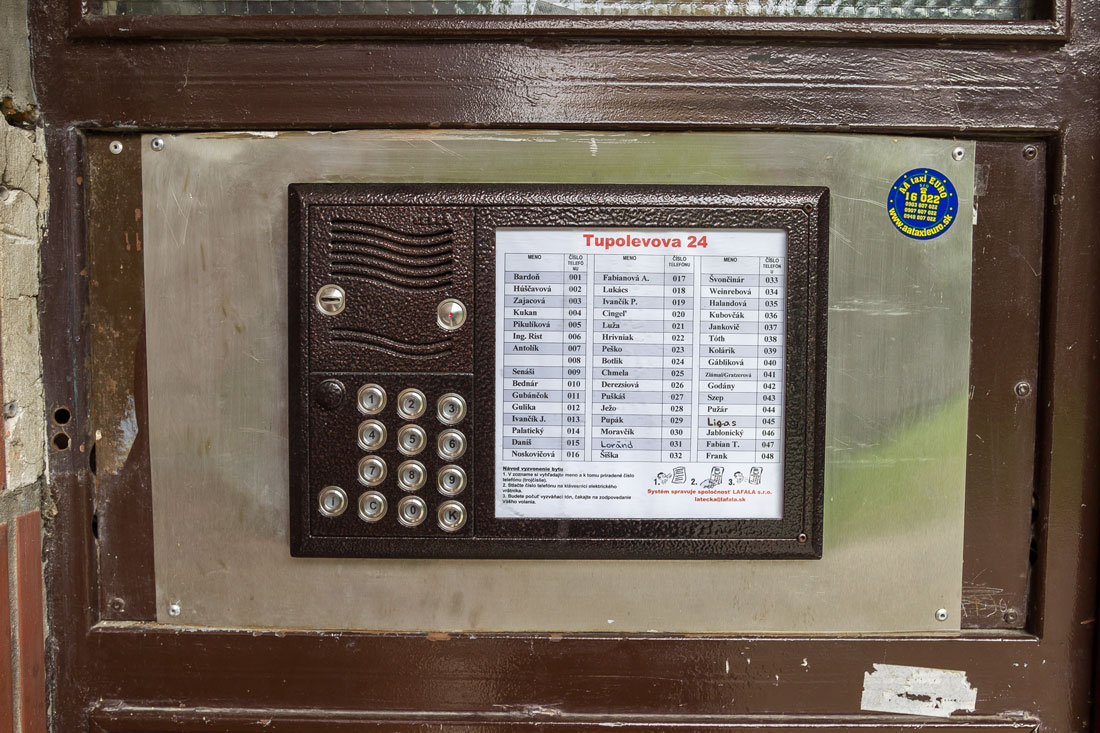

A piece of Europe — even in multi-story panel buildings, the intercoms indicate the apartments and names of all residents.

A little further, and the original landscape of panel buildings opens up. There they all stand like an archipelago. Colorful, to avoid complete greyness.

It painfully resembles Moscow. Something like Mitino, for example. Only worse. We have plenty of panel buildings too, but the way they are constructed in Bratislava... The ground floors of the buildings are occupied by shops and garage complexes, and the apartments start only from the second floor. As a result, all the buildings stand on such pedestals that are accessed by stairs and sloping paths for strollers. They stretch for half of the yard in length.

These horrible conglomerates of concrete and rusty iron are everywhere.

Such design does not solve the parking problem, and it seems impossible to demolish these structures and rebuild the garages.

Staircase on the other side of the building.

Underneath the staircases, naturally, the homeless settle. How convenient: residential buildings on top, shops with garages on the ground floor, a paved courtyard, and under the staircase — a refuge for the homeless. Everything in one place.

And here is an empty lot in the middle of nowhere. It’s probably the foundation pit of an unbuilt house. Just as terrible as the constructed ones. In any case, this overgrown pit lies between two courtyards, and it’s the only way to walk from one building to another. Can’t go around, right?

I said, the first floor is allocated for garages, and housing starts from the second floor? I was mistaken. The second floor is allocated for shops. Housing starts from the third floor.

Bratislava landscape. Will a pig find dirt everywhere? But what can I do? After all, the city really looks like that.

Here is a slightly more decent yard. There’s a overgrown stream, a nice running path.

Relatively pleasant entrance of a residential building with mailboxes.

A bonsai was found in one of the courtyards.

Modest playground.

But it’s all temporary. Schoolyard.

Bus stop.

Ticket vending machine.

Tents that resemble those from Moscow in the 90s.

Tents that don’t resemble those from Moscow in the 90s.

Modern bus.

Not a very modern bus.

Street signs.

I walked through the residential area, or even the sleeping part... the sleeping half! of Bratislava. I crossed it entirely, going from the train station in the west to the bridge in the east. I crossed the bridge, went to grab a snack at a local McDonald’s, hailed a taxi, and headed back to the west. Here, the two parts of the city are connected by the Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising. It’s a very beautiful bridge with a tall observation tower that you can climb. From up there, you can see the entire city in 360 degrees.

Here is the southern part—that very residential area. It stretches for kilometers as a continuous expanse without a single living oasis.