Minsk

It is empty in Minsk.

There is nobody at all.

The roads are empty.

The streets are empty.

The courtyards are empty.

The parks are empty.

The benches are empty.

The bus stops are empty.

It’s almost empty in the trams.

It’s completely empty at the square near the Palace of the Republic.

It’s very empty near the headquarters of the KGB. Yes, the KGB still exists in Belarus. Perhaps that’s why it’s so empty here?

In the center of Minsk, there are glass domes and an underground shopping center, just like at Manezhnaya Square.

Everything is just like in Moscow, with one exception: there are absolutely no people.

And instead of the Kremlin, there is the Government House, around which either security guards or police officers are on duty. It is advisable to film all of this from a distance because if you approach with a camera too closely, they will make you show all the photos or even order you to delete them.

Even from a distance of three hundred meters, some Chekist noticed me and became aware of my presence. He gave me a scrutinizing look, leaving no desire to approach any closer. Prior to the trip, I heard firsthand accounts of how people were detained in this area and forced to delete the photos they had taken. The pictures showed a lawn and flowers.

There is paranoia in Minsk. Let’s say, a few years ago, filming was also prohibited in the Moscow metro. But it was like this: you walk with a camera, you film. And in one out of a hundred cases, someone might notice and ask you to leave the restricted area.

It’s not like that here. At the entrance to the Minsk metro, at any station, whether in the city center or a residential area, there are two or three people stationed: usually a guard, a security officer, and a police officer. Or a guard and two police officers. And in the metro, it’s not just about filming — sometimes you can’t even enter with a camera.

If you walk with a camera hanging around your neck, they will most likely let you through. But you will definitely attract attention. Once, a security guard even rushed towards me, but I got distracted by something and turned away. And he decided not to bother me the second time. He let me pass.

Another time, I asked to take a photo of the turnstiles at the moment when the hand drops the token. I capture such a shot in every city where I descend into the metro. Nowhere and never before has anyone cared about it, not even needing to ask. But not in Minsk. They strictly prohibited even attempting to do so. Stern faces. Impossible to persuade. Not with kind words, let alone forceful insistence — they will take you to the station. They won’t bat an eye.

Filming is also prohibited at the stations, but it can be done discreetly there. However, there’s nothing worth capturing here. The Minsk metro is nothing special. This, perhaps, is the best station. The most central one.

There are TVs with advertisements hanging at the stations.

The train cars are the same as in Moscow.

The faces are the same as in Moscow.

The paranoia of Minsk runs much deeper than it may seem at first glance. One might think it’s only about the prohibition on filming the metro, KGB, and government buildings. But it goes a bit deeper. There is simply nowhere to look at the center of Minsk from a height. There are no nearby tall buildings with observation decks. They have recently started allowing access to the roof of the Hotel Belarus, but only with an escort. Moreover, you can’t see the city center from there; it’s too far away.

The only good place is the Ferris wheel in Gorky Park. The park is not far from the center, and from there, you could have a view of Independence Avenue. However, the Ferris wheel is facing the other way! Instead of a view of the center of Minsk, it offers a panorama of residential neighborhoods. The wheel was built during the Soviet era. Nowadays, such a design approach probably wouldn’t come to mind, but you can still sense its influence.

Overall, visually, Minsk is quite similar to Moscow. The main differences lie in the absence of traffic jams and relative cleanliness. However, it’s not entirely clear what has contributed to all of this.

Currently in Belarus, there is a tax on idleness. It’s an absolutely unimaginable thing in the modern world, taken from the communist past. Not only are non-working individuals required to pay an annual fine equal to 20 salaries, but when they pay this fine, the question arises: where did the non-working person get the money to pay? And now they accuse the unfortunate “idler” of illegal entrepreneurship.

But the most surprising thing is that both in Belarus and in Russia there are many supporters of such a law. They argue, “How else can we make those who don’t want to work actually work?” Or they ask, “Why should the state provide idle people with free education and healthcare?”

A reasonable response would be as follows: don’t pay for them. Ensure that they don’t receive anything for free. As for making someone work against their will, that’s a valid question. The easiest way, of course, is to do it forcefully. Those in power have all the means of coercion, from bailiffs to law enforcement agencies. The state undeniably possesses power. But try to overcome unemployment without resorting to coercion. Does the state have intellect in addition to force?

Therefore, it is not entirely clear what has achieved cleanliness in Minsk: is it due to the good work of street services or forced labor? But yes, technically clean.

However, only technically. Let’s take one of the courtyards near the city center.

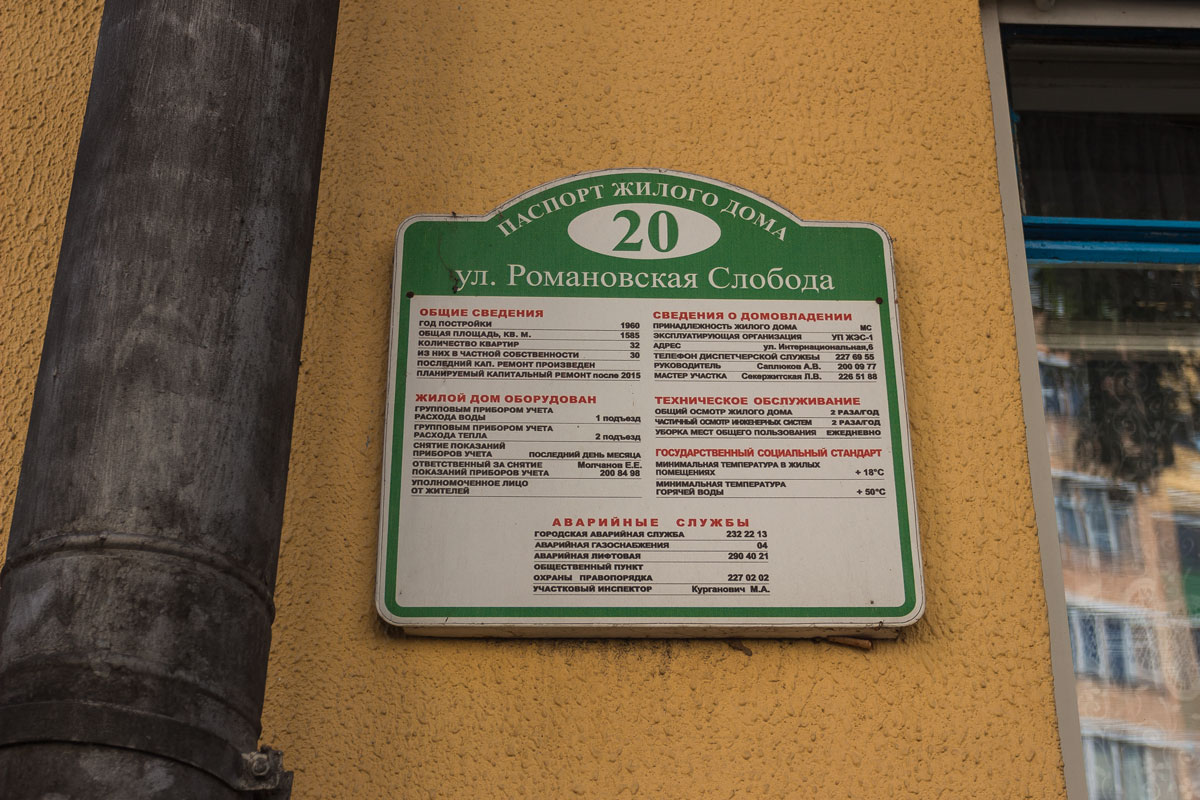

Almost every residential building has a sign displaying its “passport details.” It’s a notable artifact from the Soviet past. It’s a shame that everything is arranged so unpleasantly.

This is what a Minsk entrance looks like. Is it clean? Technically, yes. There is no garbage lying around, but the entrance itself is dilapidated. The iron door with a prison-like cage on the window is painted entirely in a layer of gray paint, cheaply acquired from the housing and utilities services somewhere at a military plant. Everything is covered up, including the hinges. Miraculously, the handle and porch have not been painted over.

They managed to repair only one side of the brick building, so the entrance splits the painted wall in half with blackened bricks. Well, there’s also cracked asphalt mixed with concrete and a curb at the entrance. In other words, it’s a typical Russian rundown apartment building, essentially.

Intercom.

The playground has not changed since Soviet times.

Another entrance in a nearby building. The house has been slightly better renovated, and the asphalt is fresh, but overall, it’s still the same.

Another residential building nearby. On the wall, painted in green, it says: “No parking for cars!” Meanwhile, the entrances lead directly to the parking area. So why shouldn’t cars be parked then?

Another courtyard and playground. This is the center of Minsk.

Perhaps it’s just an unfortunate coincidence? No, it’s not. Let’s walk around different parts of the city: we will encounter similar bare, neglected, wild courtyards everywhere.

Forget about the courtyards, even behind the Government House, there’s an empty lot as if in a village.

What is also remarkable is that almost nobody in Minsk has air conditioners. One might think that the city authorities have prohibited them. However, we’re not talking about the facades of historical buildings. Take this residential building near the city center, for example. The windows face the courtyard, with no avenues or busy roads nearby, yet there are no air conditioners. There is a suspicion that not everyone can afford to have an air conditioner. Perhaps for the same reason, the city doesn’t experience traffic jams — people don’t buy cars.

The central streets are just as bare and dull as the courtyards. Only there is more space. Huge deserted boulevards where there’s nothing to catch the eye. This is the hallmark of Minsk.

The streets are so wide that cafes, deciding to set up a summer terrace on a platform, don’t risk anything: there’s plenty of space for a tank column to pass through.

One good thing is that trees are being planted in Minsk.

The trees are young, indicating that they were recently planted. Without them, the street would probably look twice as dreary.

The architecture of Minsk is mainly represented by Soviet Neoclassicism. A residential building in the city center.

Luxurious windows of the restaurant on the ground floor with rustic curtains.

Main Post Office.

The magnificent building of the Bolshoi Theatre. Pre-war constructivism.

That very Government House with a duty Chekist. Constructivism. Repugnant building.

Across the street stands the Minsk City Executive Committee (Mingorispolkom) — modernism.

Surprisingly, next to the government buildings stands a Neo-Gothic style church. During the Soviet era, it housed the Union of Cinematographers. After the revolution, the church was returned to the believers.

Minsk is doing very poorly in terms of modern architecture. The epitome of tastelessness is the residential complex “U Troitskogo.” This monstrous jumble of buildings is actually just one residential complex. It’s simply an eyesore.

Nemiga Street is the equivalent of Moscow’s Novy Arbat. On the left are the historical districts, while on the right is an absurd concrete wall.

The architects of this horror decided to cram as much as possible into one building: the ground floor has a parking lot, the second floor has a street, entrances, and access to the courtyard. On the third floor, there are shops, cafes, and restaurants. After all of this, the residential floors begin. Access to the building is organized through a concrete bridge that passes over the road.

Excessive chaos.

The backyard of this house.

It is also worth separately mentioning the Central Department Store.

This is something beyond the limits.

By the way, the reader should have noticed that in Minsk, all the names are like those in Moscow: Academy of Sciences, Gorky Park, TsUM, Bolshoi Theatre, MKAD. For example, in Moscow, there is Pushkinskaya Square with a cinema theater and the Pepsi logo on a residential building (already removed). And in Minsk, there is Yakub Kolas Square with a philharmonic hall. Nearby is a house with the Coca-Cola logo. And this deja vu pursues throughout the city.

The building of the Minsk Library is probably the most successful modern construction. Whatever people may say about it, compared to everything else, it’s simply a gem. There’s an observation deck on top, but the library is so far from the city center that there’s nothing much to see from there. And the service in the café is like that of a Soviet canteen.

In conclusion: Minsk is an incredibly boring, dull, and useless city. Its streets are empty, and the air smells of paranoia and insecurity. There is simply nothing to do in Minsk. The entire city can be explored thoroughly in two days, then one can leave and never come back again.