Dublin

The plane from Edinburgh to Dublin takes about an hour, and a regular, non-charter flight costs only $10. Even from Moscow to St. Petersburg, it is unlikely to find a charter cheaper than $30, although the distance between the cities is only one and a half times greater, and the passenger traffic is significant.

Ireland is a country immersed in greenery and bad weather. When you step out of the plane, a stormy wind hits your face along with a drizzling rain that soaks you to the bone within seconds. Twenty minutes later, as soon as you pass through the airport, the sun is already shining over Dublin. Half an hour later, it’s pouring down again. This pattern repeats throughout the day. Welcome to Ireland.

Dublin immediately greets you with social advertisements against racism in public transportation. As the character in the movie “Once in Ireland” said, “Apologize for a black? But I’m Irish. Racism is in my blood.” Racism is indeed a problem in Ireland, primarily directed against Romanians and Nigerians.

The island of Ireland is actually divided into two countries: the Republic of Ireland with its capital in Dublin, and Northern Ireland with its capital in Belfast. There is no border control between the countries, and you can travel from one capital to another by bus in two hours. However, they are completely separate political entities. And very peculiar ones at that.

The Republic of Ireland is not part of the United Kingdom, so the currency here is the euro, not the British pound. However, the European visa does not apply here, and the British visa is valid. In neighboring Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, they accept pounds, and euros are only accepted by telephone booths, in case a lost traveler needs to make an urgent call. Perhaps somewhere along the border of the two countries, both euros and pounds are accepted, with the currency acceptance gradually changing.

An interesting fact about Northern Irish money: they are special sterling pounds with their own design, issued by the Bank of Ireland. As a currency, they are essentially indistinguishable from regular pounds. The Bank of Scotland also issues similar special pounds. In turn, Irish euro coins are minted with the symbol of the Republic of Ireland — the harp.

The Irish language. A well-known Irish comedian told a story about how he was riding a bus without a ticket during the times when encountering a ticket inspector in Irish public transport was very rare. Of course, he gets caught by an inspector and pretends not to understand the language. The inspector turns out to be a polyglot and asks him first in English, then in German, French, Spanish, Italian, and so on. After a dozen attempts, there is a silent moment, and the inspector asks, “Then what language do you speak?” “Irish,” he replied to the inspector.

This is roughly how the state of the Irish language can be described. It exists, and it has even started being taught in schools, but it is rarely spoken. Meanwhile, all English signs are always duplicated in Celtic script or simply in the Irish language.

When I arrived in Dublin, there was a full-fledged pre-election campaign for the representative of Ireland in the EU. The requirements for the campaign are quite stringent and restrictive. Candidates are prohibited from talking about themselves in any substantial way; they can only display their photo, name, main campaign slogan, and nothing more.

Despite its simplicity, the campaigning is incredibly persistent. The entire city is covered with it. Every lamppost is plastered with campaign materials.

Dublin is a city without a center. Usually, the city center is some kind of square or a small area. In Dublin, there is no such designated square. The formal center is the intersection of three roads near Trinity College, where major buses depart and it serves as a meeting point for tours and so on. However, this place is indistinguishable from the rest of the city.

The architecture of Dublin is rather modest. The majority of buildings in the city are two or three-story brick structures, poorly adorned, constructed with inexpensive materials, and lacking aesthetic taste.

This applies to the entire city. Even by the Liffey River, there are houses that are only slightly better than those built in remote areas.

Scary house in the center.

Dilapidation.

A typical house outside the city center.

In Dublin, there is only one truly interesting place where all the life revolves around — it’s the central district of the city called Temple Bar. The area is named after the Provost of Trinity College, William Temple, and the word “bar” indicates that the district is located on the riverbank and has nothing to do with drinking establishments. However, there are indeed many bars here — it is the main cultural and bar hub of the city.

Streets of Temple Bar.

Dublin’s bars are the oldest in the world. For instance, according to some claims, the bar “The Brazen Head” was established in 1198. It is highly doubtful that this is actually true. In any case, there would be no trace left of the original bar, and the building wouldn’t have stood for such a long time.

Inside one of the pubs.

Alcoholic beverages are delivered to the numerous Dublin pubs through special doors and compartments in the sidewalk; go around as you please.

Every self-respecting bar is adorned with a bunch of awards, stars, and medals. Only award-winning pubs are regarded in Dublin.

Central streets. A completely dismal sight. Sidewalks are often broken or cluttered with something. Pedestrians have been inconvenienced, people cross the road wherever they can, constantly having to step onto the roadway.

Alley. Also in the city center.

Children’s playground.

Some really run-down neighborhood, probably a ghetto. Creepy panel buildings with awful balconies where laundry is drying.

Sidewalks can be cluttered with street vendors.

Parking lot between buildings. Also in the city center.

The facades sometimes make an impression. A huge number of elements, eclectic fonts, numerous signs, vibrant colors.

The other part of the city is slightly more pleasant.

In the distance, the only interesting monument of Dublin is visible — the Spire of Light, or the Needle.

This is a huge metal tube installed in place of the monument to Nelson, which was destroyed by Irish terrorists.

Embankment.

I couldn’t figure out how to pay for the tram ride for a while. I got on it, but there were no buttons anywhere. It turned out that I needed to tap my card on the sensors located at the stops, not inside the tram itself.

Dublin taxi.

Button to call the green traffic light signal.

The pedestrian crossing emits some sort of futuristic sounds.

The bus is double-decker, like in Britain, but with its own model and color scheme.

Bus stops outside the city center are without a roof.

Tram.

Trash bin in the city center.

Mailbox. Sometimes you come across dual ones — for both incoming and outgoing mail?

Mail slots in the door.

Left-hand traffic.

Telephone.

The police is called Garda.

Lifting cranes are painted in green.

Bike rental.

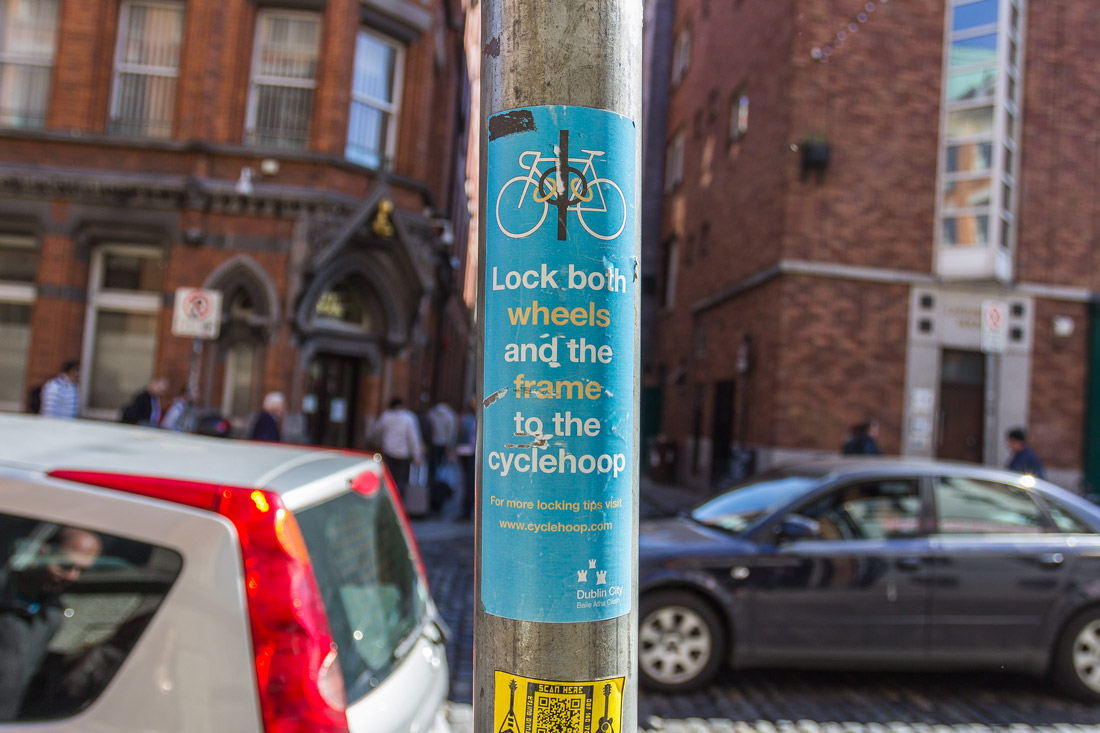

Bike parking.

Warning stickers are attached to the bike parking posts: “Be sure to secure both wheels and the frame with a lock.”

Otherwise, it will be stolen.

In general, Dublin can hardly be called a good city to live in. There is a large number of migrants, including Russians. But I wouldn’t stay in Dublin for more than a weekend — just to walk around Temple Bar and have a pint of Guinness with the Irish.